We usually start with your childhood and if you did anything in your younger years that pointed you toward the career you have now?

I grew up in Florida, South Florida. When I was in high school, I was interested in science, in some general sense. I entered undergraduate school as a physics major, I was interested in physics, and an important event happened, sort of by random, in my third year. I was TA-ing for the undergraduate labs because they didn’t have enough graduate students so they took some of the taller undergraduates and had them be TA’s. In the lab, there was a telescope, in the closet, a 10-inch Newtonian telescope, and I thought “that’s interesting”. I took it out and tried to fix it, I got it working and started looking. I went to the library and got an astronomy book, this is before the internet, of course, the “fat Abell” astronomy book, I sat down one Friday and started reading it and I just read it straight through the whole weekend. And I took out the telescope, I fixed it, got it working, it wasn’t aligned properly but it was basically in good shape, and I looked at Saturn and the Great Nebula in Orion.

Once I set it up in the parking lot of the campus and other people came and asked what I was looking at, and I liked that – both the explanation of science and the science itself. Then a roommate told me about a rocket launch, and we went to watch it from the viewing area. We watched the last Saturn V launch, it was so impressive, even years later when I watched other launches, I still remember that one and how really impressive it was. I guess because it was the first one and I had never imagined how powerful that was.

Sometime later I visited the University of Colorado and talked with a professor of physics and I said “I’m interested in applying here, I like the town and I like the school”, and although it was late August he said “Well, it turns out that one of our grad students just declined acceptance so we have an empty slot. Can you start next week?” And I said “Sure!” So, I got in my car and raced back to Florida, put everything I owned in the back of my Toyota and drove back to Colorado and started graduate school! So, it was one of those random chance events. And while I was in graduate school Viking landed on Mars, – I started graduate school in August 1976 and Viking landed in July and results were starting to come in, speakers were coming to our department symposiums, talking about Mars and there was a little group of us in an office, which I called the “graduate student ghetto”. It was one office with about six grad students and Carol Stoker was in the desk next to me.

We had questions like, was there life on Mars? It wasn’t really clear. It wasn’t old news like it is now. The debate on Viking hadn’t crystallized into these opposing camps. It was really quite exciting and so we got into it and basically I’ve been doing the same thing ever since that first year of grad school, this connection to astronomy and space and exploration, and the Saturn V, and Mars.

And here I am, literally 40 years later, still doing the same darn thing! And at the time if somebody had asked me “Is this a deep interest for you?” I would have said “no, it’s something I’m gonna do for a few months, it’s just interesting, it’s the topic of the month, and with Carol sitting in the chair next to me, it’s something to do together. It’s a passing interest” is what I would have said. But I got deeper and deeper into it and the question of life, and why is there life on Earth and not Mars, and was there life on Mars, and would there be life on other planets, and how would we find it, and how would we send humans to go look for it? These sound like very simple questions, but 40 years later we’re still pushing on it.

Now, sort of in the background through all this is watching Star Trek! When I was an undergraduate, back in the days of TV, we had a dorm and there were two rooms, one on each floor, that had a TV, and that was it. It wasn’t like today where you can get access to the TV just about anywhere. So to watch Star Trek you had to first get the newspaper and find out when it was going to be on and then go to that room and turn the TV on to that channel, so I would do that regularly and watch Star Trek. And it was pretty amazing. In retrospect at the time, you’ve must remember this was the time of Watergate and the Vietnam war, and so not a positive period and a lot of the negativity was being blamed on science. So, the notion that science and technology could play a positive role in the future was refreshing and interesting and I resonated with it, that it wasn’t going to be atom bombs and atomic wars from now on, and napalm and all that, but that technology and space exploration could be part of a positive future and Star Trek was sort of the window for that. So it was kind of a parallel theme along with the other events that were specific to me, of course.

And then when I was in grad school, this is another chance occurrence, I was sitting in my office and one of the other grad students comes by and shows me an advertisement in Science, a little tiny square classified ad, saying “NASA is starting a planetary biology summer intern program: first year”. And he said, “You ought to apply to this”. And I said, “You know, I should.” So, I wrote in, got the application material, applied to it, and I was selected.

They told me, “We’re going to send you to Florida to work with Imre Friedmann who does research in Antarctica on organisms that live inside rocks.” I knew of his work, I had his papers and I said: “OK, that’s great”. I wasn’t keen on going back to Florida but OK, “if that’s where it is, that’s where it is”. Florida was one of those places I was happy to leave and I didn’t look back. I never wanted to move back to that muggy, swampy area again, but I said: “that’s fine”. I called up Imre and I got his wife Rosalie on the phone, and she said, “well we’re going to be in Europe all summer, we can’t have a summer intern, we’re not going to be here”. I called Boston University, Lynn Margulis was the organizer and I said, “well, I can’t go to Florida because no one will be there”, and they said, “OK, we’ll find you someplace else”. And a couple of days later they called me up and said “what about NASA Ames, would you be interested in going there, it’s in California?” And I said, “Oh, yeah!” And I knew of course that it would be working with Jim Pollack.

This [my current office] was Jim’s office, by the way, that’s his lion there and that’s his lion up there and that’s his chalkboard. Anyway, I said, “that would be great!” And the next day I got a call from Jim Pollack and he basically gave me an exam over the phone. He didn’t want somebody coming who didn’t know what they were doing. I didn’t realize it at the time, but he said “Hi, I’m Jim Pollack” and he basically quizzed me on several things, and by chance it turned out that he was reading the only paper I published as a grad student, he was reading it for the work that he was doing, and so he said “Are you the Chris McKay that worked on this paper?” And I said yes. And he said, “have you done this, have you done that?” And then at the end, he said: “OK, you can come out here”. It wasn’t quite that blunt but he was basically checking to make sure I wasn’t worthless.

I came out here for the summer in 1980 to work with Jim Pollack, and we would meet in this office and I would write results on that chalkboard and I really liked Ames because here were some of the best people in the world, Jim Pollack, Brian Toon, and so on, and everybody was sort of on the same team, we were all doing science together. It was a very level organization, a people approach very much unlike a university. My university and my department weren’t bad but there are professors and department chairs and students and grad students, it was very hierarchical, and I guess it has to be. And I was just amazed at how much I liked this arrangement, and right then and there I said: “this is where I am going for a postdoc”.

There is a point I make to students, about random events. If I had gone to grad school a year later, or if I hadn’t found that telescope, I might be doing something else, I’d probably enjoy it too, I’d probably be doing particle physics or maybe cosmology, so you end up where you are, not because of some predetermined path but because there are opportunities and you’re interested and you follow them. And you can’t angst over it.

One of the people we interviewed remembers her earliest attraction to science was looking out the car window and seeing clouds and being just fascinated by their formations and different types and everything and became interested in atmosphere and was going to go into meteorology and then made the connection to, hey, planets have atmospheres too, and so that’s how she went with that career interest.

Yeah, and the opposite is true. Growing up in Florida, as one of my professors put it, there’s not a rock within a thousand miles of South Florida, it’s just sedimentary and flat – there’s no geology – and I never understood why people were interested in geology. And then the first time I left Florida was to drive to Colorado and I drove through Tennessee and the Appalachians and up and down these cliffs and hills, and rocks and I said “Oh! This is why they do geology!” But in Florida, there is no geology. The only thing that’s like a hill is the freeway overpass! So, it’s kind of funny, I think if I’d have grown up in Colorado I might be more of a geologist and also the meteorology, the mountain waves and things, there’s a lot of interesting stuff there.

Anyway, I came to Ames for the summer and Imre ended up coming here for a visit that summer and he called me up one day I remember because I was in the middle of a letter to a friend of mine and I said, “Uh, the phone rang” and there was Imre. I went over to meet with him and after a conversation with him I said: “Sure, I can work with you”. He needed somebody with a physics, math and computer background to work with him in Antarctica studying these endoliths and I guess that’s what I would have worked on if I had gone to Florida with him, and I said: “great, count me in!”. I ended up going to Antarctica with him in 1980 while I was still a grad student and that was my first connection to fieldwork in extreme environments.

That summer, being here, meeting Imre and working with Jim was really another of those random pivotal changes. All trace back to that little ad in the paper in Science magazine that I never noticed but another grad student noticed and said: “Hey, you should be interested in this”. Also, the Viking landing when I was in grad school, these sorts of random events shaped up, so I came here to Ames that summer, and then as a postdoc for two years and in retrospect I was silly, I didn’t apply anywhere else. This is the only job I applied for. I didn’t know what I’d do if I didn’t come here, I just sort of decided I was going to Ames. I didn’t know what Ames had decided, I just assumed they would agree. In retrospect, I would never advise a student to do that. Apply to many places, you never know. And then you have options and you can decide. I only applied to one grad school and only applied to one research lab! I just sort of dropped into it, and when I came here all the reasons why I wanted to come here were still there and Jim was here and I worked with him until he passed away about ten or twelve years later, from cancer. So, from starting undergraduate school to coming here to Ames, things were happening and my path was changing in ways that were unpredictable, and then once I came here it’s the same ever since! The same thing: life, Mars, search for life elsewhere, field work, so there’ve been no more twists and turns!

But during the time you’ve been here, almost 40 years, there have surely been some notable discoveries or interesting things that you have been involved in, could you give us one or two of those?

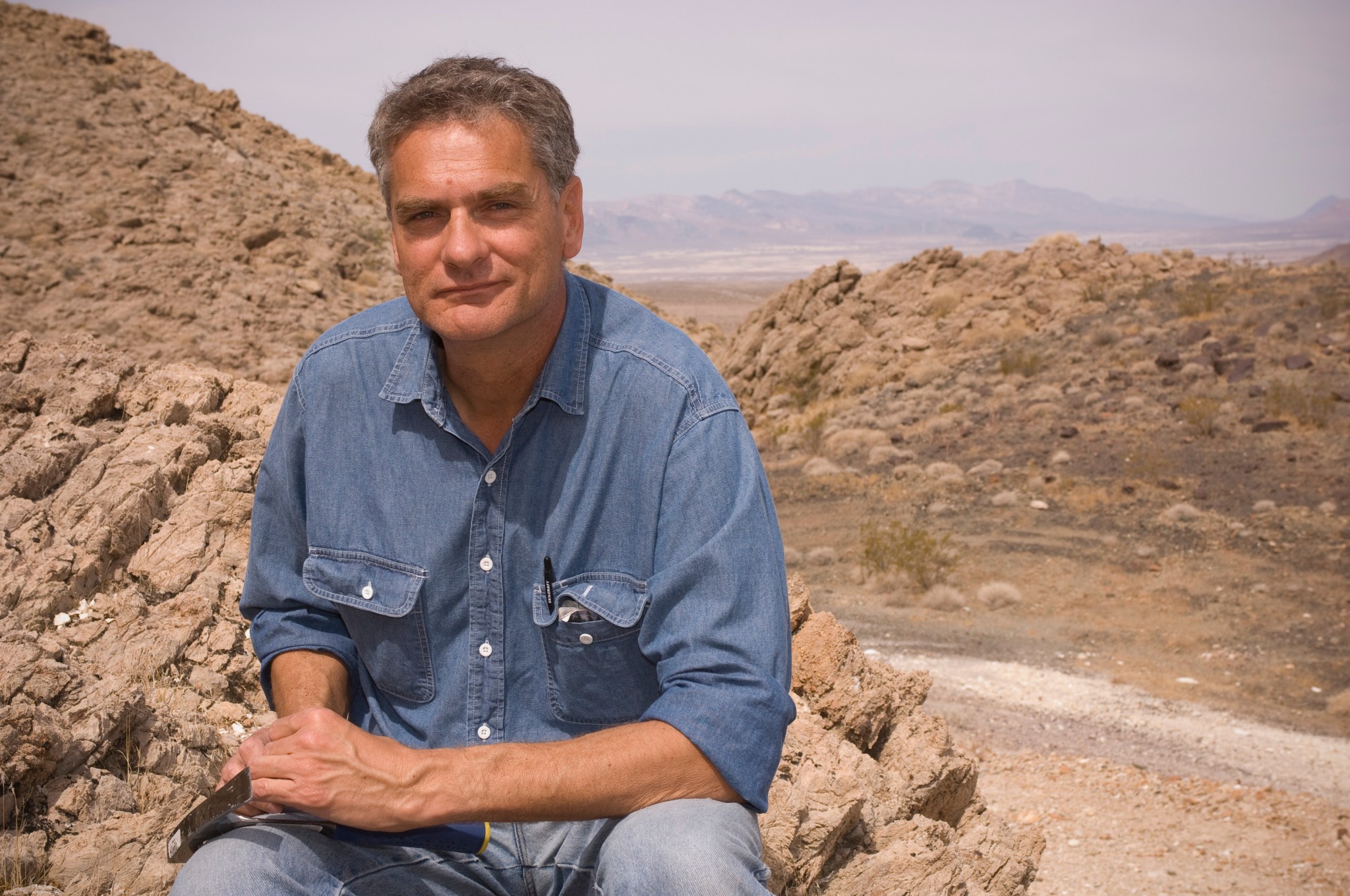

I think the two highlights would be on earth and in space. On earth, it’s the work in the Atacama desert, the driest place on earth, and Alfonso [Davila] has been heavily involved in that. And the work in the Antarctic. We look for the places on earth that are very low in biology. You can even argue that the places we study are uninhabitable. Earth is a habitable world but there are a few places which are not habitable and these are two of them. A lot of our effort, my effort, has been studying those environments and using that as a way to inform how would we search for life on Mars in particular, but now also on Enceladus [a moon of Saturn] and Europa [a moon of Jupiter].

So that’s filled up many, many years, with field trips and we are still doing that, in fact I just got an email this morning from a team that was down in Antarctica, that just came back, and they just took their first shower since October (laughs, now end of December) and I thought, “Oh yeah, I remember that!” There was a time when that was a feature, not a problem! Not anymore! (laughs).

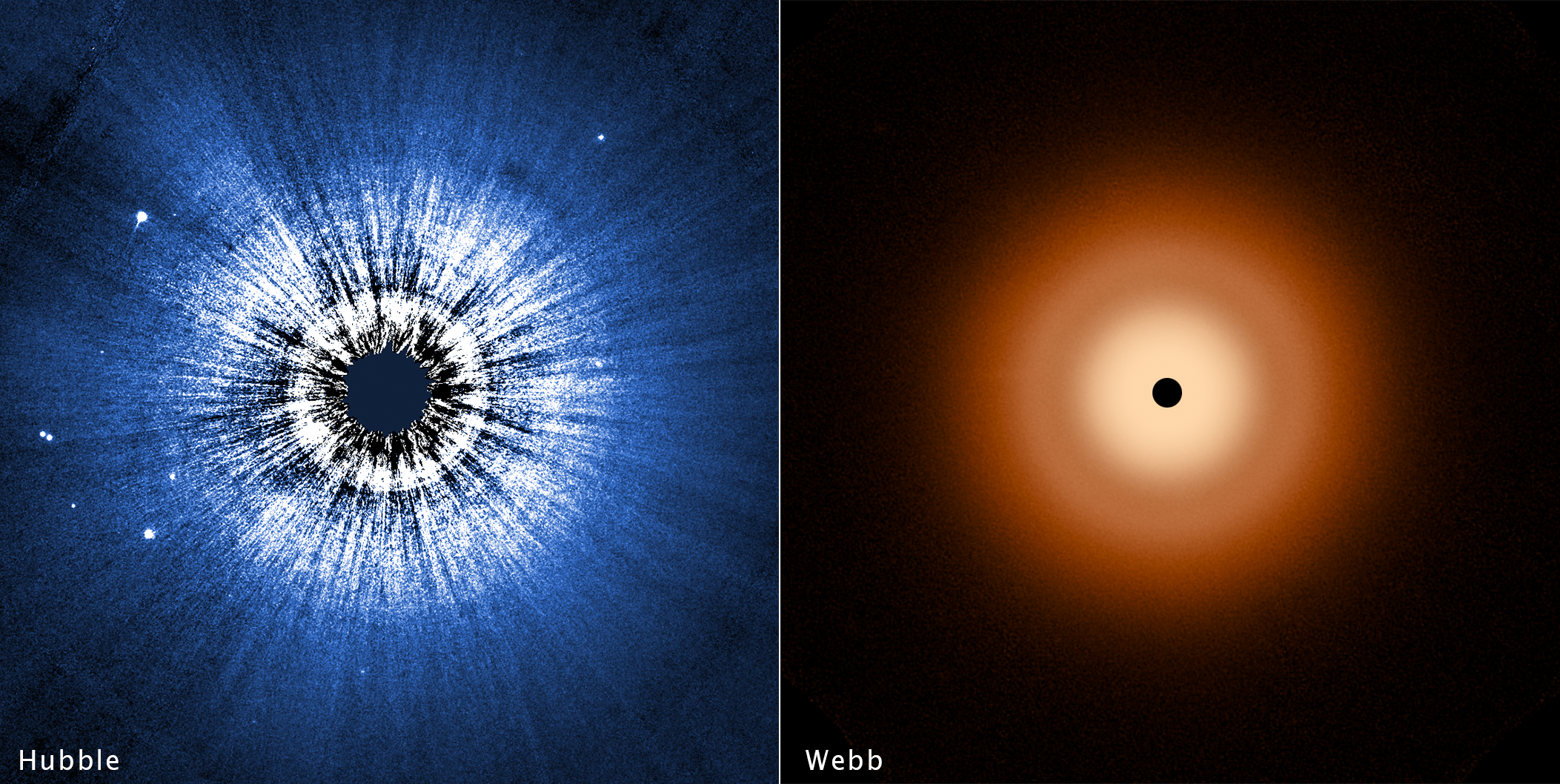

And the second thing is what we’ve been learning in space. As a very important highlight in the positive sense is Enceladus. In 2005 Cassini arrived in the Saturn system and discovered water plumes coming out of Enceladus and that’s just really spectacular. The plume has organics in it and so we‘ve really been pushing with renewed enthusiasm for the idea of flying through that plume and sampling it. Certainly, there is no lack of new challenges and exciting opportunities. And on Mars we’re working on missions to do life detection as well, maybe someday humans will go.

You’re looking for life at whatever level that it might exist?

Right, right. If it’s alive I don’t care how small it is or how dumb it is. A lot of people are interested in extraterrestrial intelligent life and that’s great but any life, from my point of view, anything that’s alive would be phenomenal, anywhere, anything alive, and even if it’s dead, it’s still phenomenal. Even dead, I’d be interested, but if it was alive it would be fabulous!

What is a typical day like for you, if there is such a thing, and what do you like best and least about your job?

Well, typical days come in two sorts. One is out in the field. Going out and trying to do fieldwork, not really anything typical but to be out in the field out in Antarctica or in the Mojave, or in the Atacama. And what I like about those days is that we are all isolated out together. Typically at the end of the day, we all come in and we just sit around the campfire, metaphorically speaking, and talk science. It’s wonderful! I first did that with Imre in Antarctica, in tents in Antarctica, and we try to keep that tradition in my fieldwork. At the end of the day we all get together, we all eat together, and we talk about what we did and what we’re doing, and the conversation can wander off into all sorts of science areas when you have an interesting mix of people out in the field with you.

The other typical day is in the office when we are working on data or with a postdoc or student working on a paper. Those are what typical days are like.

What I like the most about doing what we’re doing is the very idea that we are sending machines to other worlds to search for life. When I think about that, it is just amazing. And I get to be involved in that! That is really a very high level of motivation and it gets me through the bad things.

And the bad things are mostly all the proposals we have to write. I must be spending, depending on the time of year, about a third of my time writing proposals. As you know the success rate of these proposals is really pretty low, some programs less than 10%. It’s almost like buying a lottery ticket, but it takes a lot more effort. It’s kind of discouraging but I don’t know what else you can do. So we just do it. We’ve had enough successes with this system, that’s how we wound up going to the Atacama, which was an important part of work for us. It was the third proposal I wrote that got selected. Going to the Antarctic for the big work we did a few years ago it was probably the fourth proposal, so it’s just the price of doing business, you’ve just gotta do it.

You’ve already touched on this but what advice would you give to a young aspiring planetary scientist or astrophysicist, who would like to have a career like you’ve had?

I often get emails from people that basically say, “Hey, I want to do what you do, what should I do?” And I tell them: one, you’ve gotta get a Ph.D. if you want to be a researcher. And two, don’t study astrobiology. Don’t study astrobiology! Astrobiology is a way to apply the core discipline that you must learn, so you want to be a physicist or a chemist or a biologist, or geologist and then you want to apply that, you want to do all the things that those people do and then for extra you can apply your discipline to astrobiology. Astrobiology is multi-disciplinary. Don’t think that you’re going to go to school and do a little of this and a little of that, that’s a recipe for not knowing how to do anything. My own bias is, get a strong foundation in math and physics, that’s what I did, and I found that to be very useful. I can often contribute to a group, a team, because of my expertise in math and physics.

First, be an expert in something. Then the second thing I tell them is, just the randomness, interesting opportunities come up and follow them if they’re interesting and you never know where it’s going to go. And again, I point to my experience. If somebody had asked me in my senior year of high school what would you be doing or told me “here’s what you’ll be doing”, I can’t imagine that‘s what I’d be doing, but it was interesting.

What do you for fun?

Well, I have a lot of fun in what I do! I hate to admit it to people who want to have a sharp dichotomy between work and enjoyment, but to me, the most fun days I remember were days out in the field, out in the Mojave or in the Atacama or even the Antarctic, even though it’s minus 20 degrees and we’re freezing cold. There we do things that people in other jobs pay to go do. I hear about people who are accountants or doctors and their idea of fun is to leave the office and go mountain climbing, right? But I do mountain climbing in the Antarctic and that’s a job, and we are doing it with a purpose and we have a team of us that are all intent on working together, focused on trying to understand some problem, so it’s not just to make it to the top, it’s to do it with a purpose. I can’t imagine a better way to enjoy yourself.

I remember John Rummell who was at NASA headquarters, and I told him, I put in a travel request, and said I’m going to the desert in Namibia in Africa. And he wrote back “is this a vacation or is it work?” I didn’t give him my honest answer. I said “John, we’re sleeping in the dirt, we’re eating dirt, we’re digging in the dirt if you want to call that a vacation, you can. I call it, work.” So he approved the travel. We were living out in the field, we were living in this old ramshackle desert research station and our day was spent out digging in the dirt but to me, that was the best thing possible. It was what I wanted to be doing. I wouldn’t rather be anywhere. And I wasn’t working on a proposal! So that’s what I really do for fun.

I sense that from your enthusiasm and you are blessed to have that kind of life. So, would there be anything outside of the work environment here that you might want to share about your personal life, family life, hobbies, interests, or other things besides the work here?

The general thing I tell people, particularly postdocs coming in is, I work hard, I work long hours sometimes, and I go out to extreme places, but I don’t do it at the expense of my family or my outside life, or my life. I reject the notion that you have to be a slave to the job. I tell the postdocs who work with me, that someone works best when they’re happy. If you want to work at home because your kid’s sick, work at home. Don’t feel like you’ve gotta drag into Ames and sit in the office. Work whatever hours you want. If you want to work from 2:00 to 5:00 in the morning, work from 2:00 to 5:00 in the morning. Like what you are doing, be motivated by what you’re doing. We’re lucky in our field that we can do that. It’s not like we’ve got a job where we have to show up [at a specific time]. I used to work as a busboy. Obviously, I can’t work at home as a busboy! But we’re in jobs now where you can do that and I try to encourage them to find whatever balance between their work and home that suits them and if they find that balance and they are happy with that, they’ll do better work, more creative work, and better work. I’ve tried to make Ames a family friendly place in that sense. I always encourage people to do good work and work hard but work hard in the context of a life that’s enjoyable and that fulfills your needs and where your primary responsibility is to be a human being, not to be a cog in the science machine. That’s not your primary responsibility. And if you’re a good human being, you’ll be a good partner in the scientific endeavor, and you’ll do better.

What accomplishment are you most proud of that’s not science related?

Not literally science related is probably the Spaceward Bound, where we brought teachers and students out to the field. About fifteen years ago we started an experiment together with Liza Coe in the Education Office. Prior to then our field trips were all scientists and grad students doing science, but we decided to try the idea of recruiting teachers to come with us, to basically work with us in the field and then take that experience back to their classrooms. The way a lot of teachers do in their professional development is they go to canned lectures, “You will go here for a week and you will learn this, and this, and this, and on day two you will learn this, and on day three you will learn that.” And that’s OK, that’s good, but we don’t do that in the field. We don’t know what we’re going to learn. So I just said to the teachers, “Well, come along. We’ll figure it out”. I was worried that the teachers would be uncomfortable with the unstructured nature of it and the scientists would be uncomfortable with having teachers who aren’t professional scientists on board. And that it would be acid and water, it wouldn’t work. But in fact, it was the opposite. The teachers would sometimes come to me in the evening and say “what are we doing tomorrow?” And I’d say “I have no idea!” “We’re going to have a meeting tonight to talk about what we did and what we want to do and then we’ll decide. And you’re welcome to be part of that conversation.” At first, they would think I was kidding but then they realized that that’s really how field science is done and they loved it. They really got into it. And the scientists, rather than not objecting to the teachers being there, they loved that there were these smart, but not in the same area, teachers, who were enthusiastic and were asking good questions. It worked out well. We’ve continued doing that and it was really very good and the teachers enjoyed it and the scientists enjoyed it. It was a good model.

We certainly feel your personality and your passion and is there anything about your self that we haven’t touched on that you might want to share for the wider audience of your colleagues here who only see you mostly in this context?

No. I guess the other thing I tell people is to go exercise every day. You’ve probably seen me walk down the hall in my shorts. I go running, Ames is great for that, we have a shower on the fourth floor, we’re the only NASA center with a lap pool, so every day I either go running or swimming. And I insist on it. I’ll walk out of a meeting with the Center Director, and say “Hey, I’ve gotta run!” And I’ve literally gotta run, because, you know, it’s not negotiable! It’s part of that same attitude that I’ve gotta be the healthy, happy person in order to be a good scientist. Don’t let your intellectual interests be bounded by what you’re doing on a particular project. Read history and be as whole and complete a human being as you can be. That will help you do your science. If you do nothing but Mars astrobiology 24 hours a day you will do it more poorly than if you exercise and read and spend time with your family and do all the things that are important to you, whatever they are, and they are different for different people. Then you’ll do better in your creative part.

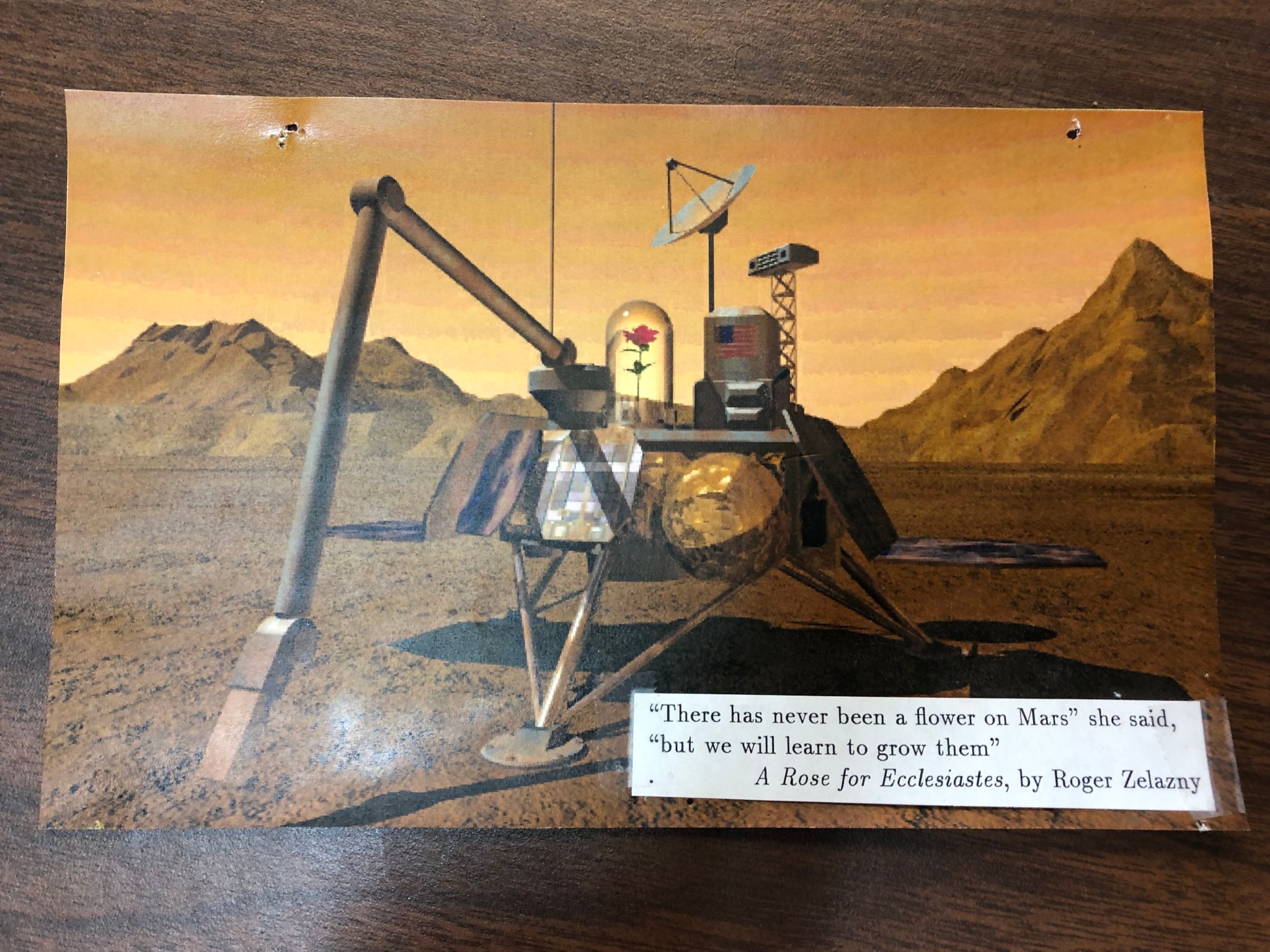

That’s very sound advice for sure. So, the last couple of things we ask, and you can take your time and get back to us later on it, we’d like to ask if you have a favorite space image, something related to your work, you know sometimes we see your favorite one in your office. If you have one that represents the work you are doing, or that you particularly like, or maybe even that you took yourself. And also, if you have a favorite quote, or someone or something who inspires you.

A good candidate would be that one right up there at the top, one that is both the lander on Mars and that has a quote attached to it, both a picture and a quote.

Interview conducted by Fred and Sara on 12/20/18