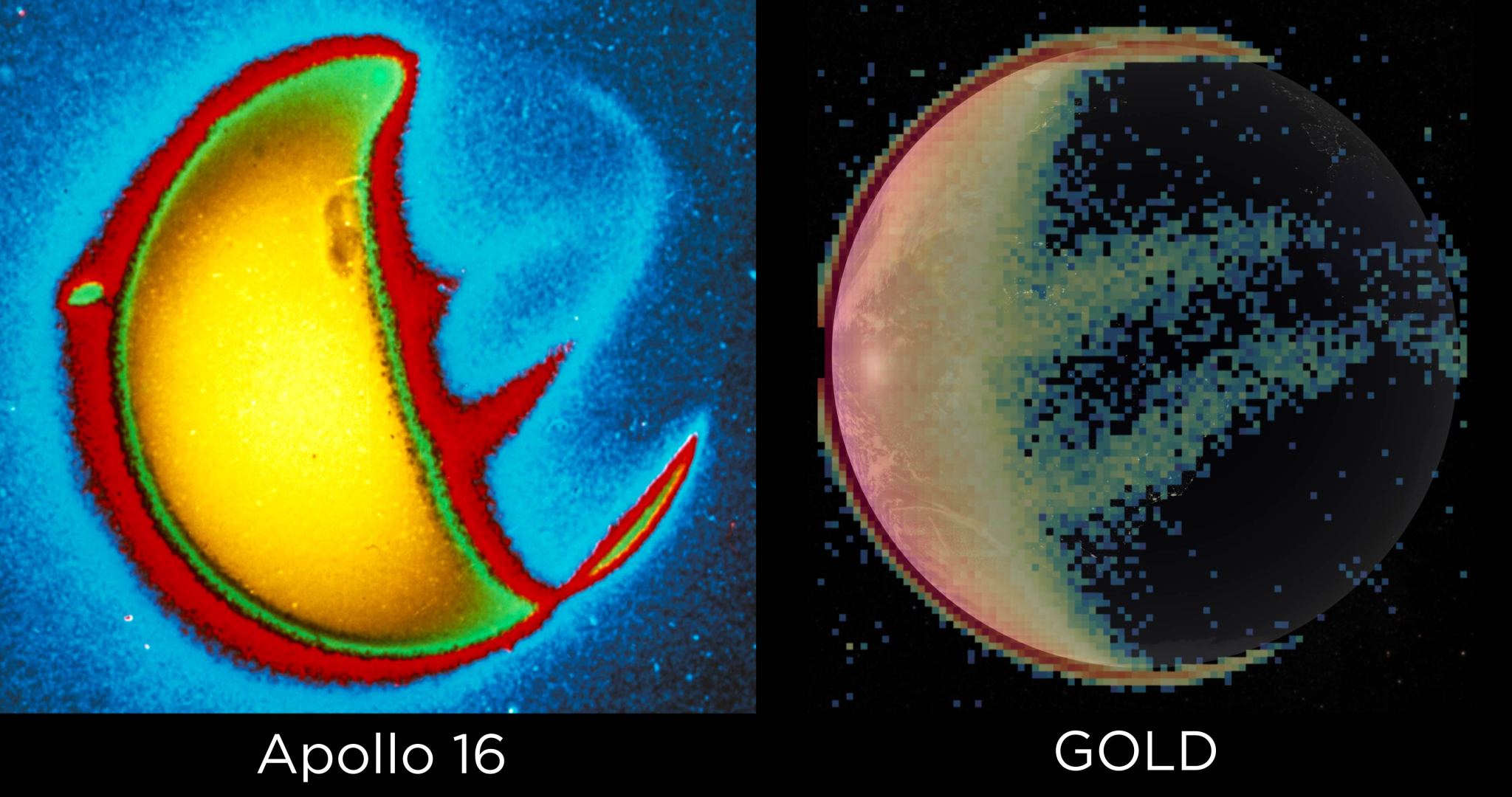

In 1972, Apollo 16 astronauts John Young and Charles Duke stood on the Moon and looked back at Earth. From the lunar surface, they took a picture of Earth like none before: the first view of our planet in far ultraviolet light.

This picture highlights Earth’s ionosphere, a region of the upper atmosphere that is mostly invisible to our eyes — aside from aurora or airglow, if you’re in the right place at the right time — but shines in ultraviolet, or UV, wavelengths of light. Named for the electrically charged ions that move about freely there, the ionosphere absorbs UV light from the Sun and re-emits it to space. The effect can be seen in this UV image. The Sun-facing side of Earth is bright. The rest of the planet, which is not receiving UV light from the Sun, remains dark, shrouded in night.

Attentive observers may notice three strips of UV emission that extend onto Earth’s night side. The two strips just above and below the equator are known as the Appleton Anomaly. They mark where Earth’s magnetic field interacts with the upper ionosphere to trigger dense fountains of uprising plasma. The southernmost strip is UV light from the aurora australis, or the Southern Lights.

Launched in 2018, NASA’s GOLD mission — short for Global-scale Observations of the Limb and Disk — is now one of our key tools for ionosphere observations, providing the first day-to-day weather measurements of the region. By measuring far UV light, GOLD tracks changes in the ionosphere’s ever-changing temperature, density and composition — enabling scientists to piece together the forces that shape conditions in a part of the atmosphere critical to many Earth-orbiting satellites and everyday technology, including the successful transmission of radio signals and GPS.

This visualization of GOLD data from March 2019 shows the transition from day to night, as well as the Appleton anomaly, which appears as two horizontal arcs of light that extend into night. The aurora can be seen at the top and bottom of Earth, also extending into night.

By Miles Hatfield and Lina Tran

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.