Have you seen our previous interviews?

I’ve seen the ones you’ve done, but to be honest, I haven’t had the chance to think a lot about your questions, so this going to be mostly improvisation!

Where are you from? Your childhood and if there was anything from your young years that sort of pointed you to where you are now?

I was born in the former U.S.S.R., in what is now Ukraine. I’ve always been interested in astronomy and space as far back as I can remember. I remember looking at the night sky when I was in kindergarten and my first memory of the night sky is seeing a star moving, which must have been a satellite, and I was amazed how you can have something like that in the sky. The night sky always looked amazing and beautiful to me. Later on, I kept reading astronomy books and space books, always gravitating towards that, those topics have always been on my mind. I get a particularly strong visceral response to seeing, to imagining, the vastness of space. Every time when I see the Earth in a movie as a globe and the stars around it, I get what astronauts call the overview effect, which is this feeling that the Earth is small and precious, and that all the wars and conflicts and the dark parts of humanity are senseless next to the vastness and the beauty of the universe, and that we are all in this together. The astronauts get the “overview effect” for real when they see the Earth with their own eyes, but I feel it just by looking at images of the Earth and the night sky. That sense of awe is what initially drew me to this field.

The first astronauts on the Moon said that very thing, they saw this Earth out there, how fragile it was, how there were no borders, how in this vast blackness of space it was an oasis, and that we need to be good husbands, we need to treat her well, because this is the only place we have.

The entire humanity is inside that fragile spot in the universe.

You said you enjoyed seeing the night sky in Ukraine. Were you in an area that wasn’t highly urbanized so there wasn’t a lot of ambient light to interfere?

I was in the capital of Ukraine, Kiev, in the center of downtown.

Did you have to go out of town to be able to see something?

Well, surprisingly, you could still see a fair number of stars there. Also, when I was a kid (1980s), there was less light pollution, and Kiev itself wasn’t as lit up as some of the other big cities of the world, so you could see a fair number of stars.

People sometimes are really surprised when they get to see the sky in a really dark place!

Did this interest or emotional response to seeing these things point you toward any choices you made in your schooling?

I was always interested in math and the sciences, and my parents were very good at encouraging me to study that, so I owe a lot to them. Even though I didn’t go into astronomy specifically in my studies, I’ve always done a lot of science and math and focused on those areas in my school.

Was that common by the way, that a lot of students focused on those topics?

I would say the standard math and science curriculum in the U.S.S.R. was a few grades ahead of the US, which actually enabled me to skip a few grades when I came to the US. My family immigrated to the US (New York City) when I was 12, so I did grades 1 through 6 in the U.S.S.R. Then I started junior high school in grade 8, skipping 7th. I also dropped out after my 11th grade in high school because I ran out of science and math courses there and I knew I wasn’t going to do well in the liberal arts!

You missed your senior year!

I know, senioritis!

I went to math camp during the summer and I met someone who also ran out of math courses and science courses in their high school, and they got into college one year early without having finished their high school, so I decided to try the same thing. My parents also encouraged me to do that and I ended up succeeding and getting into a college without getting a high school diploma. If you really want something, don’t be afraid to stray off the beaten path!

What prompted the move from Ukraine by your family coming here?

Several things, one is that my family is Jewish, or at least by the definitions of the U.S.S.R., and there was a lot of anti-semitism there, including at the state level. My father is Jewish and my mother is not, but families like ours were considered Jewish. The discrimination was unofficial, so you would not necessarily feel it in everyday life, but my father was denied a lot of the opportunities that he would otherwise have. In addition, this was the late 80s and early 90’s, with the whole system and the economy on the verge of collapsing, and inflation is probably a factor of a million. At the same time, the iron curtain was fading and the U.S. has been welcoming refugees, so we came as part of a Jewish refugee wave in 1991.

I personally did not feel a lot of this. When you are young you don’t feel a lot of these things that your parents feel, but I’m very grateful to them for enabling a better future for me and kind of saving me from the political and economic upheavals that I would have otherwise experienced in those times in the early ’90s.

So, you are in New York and you’ve finished with high school, which college did you go to, why did you choose that one, and what was your course of study?

I was lucky enough to get into Princeton. It was nearby, I was young, only 16 at the time, so it made sense for me to be close to my parents before I was over 18, so that was part of the decision. I visited beforehand, I liked it, and since I only applied to one school early, the choice was easy. I majored in electrical engineering with 2 certificate programs (which are like minors): applied math and engineering in physics.

I originally started out thinking that I wanted to major in math but engineering appealed to me and as I said, I wasn’t that good at liberal arts. To be clear, I liked liberal arts very much, I love reading classical literature, but I could not compete in liberal arts in a place like Princeton, so I wanted to focus my studies on technical subjects. I discovered that as an engineering major, I could take all the math courses that a math major would, but the engineering department had fewer liberal arts requirements. I’ve always loved applied science as well as theoretical science, even though I tend to be more on the theoretical side than a lot of my peers. I don’t remember exactly why I picked electrical engineering as opposed to some other kind of engineering but I think that it had to do with the fact that there was a lot of math and analysis, including one of my favorite concepts – the Fourier Transform (which I use extensively in my job today) — and that appealed to me.

So, did you graduate in three years from Princeton? (asked in jest).

No, I did not. I can’t keep pulling that off! And even though I didn’t actually graduate from high school I did eventually have to get a GED because it was required for graduate school admissions. Then after I completed Princeton I knew I wanted to study more and so I applied to grad schools. I ended up going to Stanford and that had a lot to do with the fact that Silicon Valley was very hot at that time, the center of the dot.com bubble, and that appealed to me quite a bit. I still was very interested in astronomy and space, and my friends at Princeton made fun of me (in a friendly way) for wanting to go to Mars and reading books about space exploration and expanding humanity and all of that. But, somehow at that time, space to me seemed more like a hobby than a profession, particularly since the internet was booming, the dotcoms were booming, high-tech was very hot, so I got seduced by Silicon Valley, and Stanford would put me in the midst of it. My other choice was Berkeley, so I had a tough choice between them.

It’s hard to go wrong with either one of those.

I ended up studying optics at Stanford, partly because fiber-optic telecommunications was on the rise in the early part of this new century, the “oughts” decade. I jumped on that bandwagon and it was a fun ride, that’s where I learned a lot of the optical engineering that I’m applying in my job today. I also worked with deformable mirrors, which are important in telecommunications as well as in astronomy. But then a few things made me reconsider entrepreneurship and the industrial path as a career. One of them was that the telecom bubble burst, as the dot.com bubble burst before it, so I came to realize that these bubbles are not sustainable, they come and then they burst. I had a lot of friends who went to work for companies and were doing well for a few years but then the companies started going out of business, and I saw a lot of people coming back to grad school without having realized the dream of their companies becoming big.

I also took a business class and I liked it very much but I discovered that to really succeed in business, or as an entrepreneur, you needed to be a businessperson first, and a scientist second, or at least that’s how it seemed to me. I wasn’t as competitive in business as I was in science. I still liked the business side very much, but I decided I should look for areas and career paths where science was emphasized a lot more. (Though now I’m finding that you have to be a very good politician to succeed at NASA! [laughs].)

You anticipated my question: Princeton to Stanford got you 3,000 miles closer, but what got you the last 10 miles, from Stanford to Ames?

Well, I actually went back to Princeton to do a postdoc. What ultimately tipped my decision to finally take the plunge into astronomy as a profession was the realization of how close we are to discovering earthlike planets. This was in 2004. I knew that astronomers were discovering large planets, but habitable planets are so much smaller that I thought it was still many decades or even centuries in the future. Even in the 23rd century of Star Trek they don’t know ahead of time if a star has an earthlike planet. They have to go there and scan the system and then they realize, OK, it has these types of planets. So, for a long time, my impression had been: OK, astronomers can detect these large planets, but detecting Earth-like planets was beyond the foreseeable horizon. But when I read that people were talking about doing missions and projects that could discover earthlike planets, that was a big turning point for me, and a big revelation about how far we’ve come. It made me proud of humanity that we achieved this level of advancement, where we could do these things, and I wanted to be a part of it.

A turning point happened at my 5th-year reunion at Princeton. These reunions are a big thing, a lot of times half the class shows up for the big years. The person who was to be my postdoc advisor, who I didn’t know at the time, gave a talk on his work, which was developing concepts and methods to discover earthlike planets. His name is Jeremy Kasdin. He gave a talk together with two other professors, David Spergel, and Michael Littman. I had taken a class with Michael Littman as an undergraduate and did very well, but I didn’t know Dave or Jeremy. And throughout that lecture, my mind was being blown every five minutes about things that I had not realized before, like that NASA was planning a mission to discover earthlike planets, called the Terrestrial Planet Finder. They were working on technologies to develop this mission at Princeton, working together with NASA and other institutions. And here’s the kicker: the technology that they were working on had a lot to do with the Fourier Transform, one of my favorite concepts. So every five minutes a big revelation just clicked, and right after the talk I was really excited, and I went right up to talk to Jeremy, without any introduction, and I said, “You don’t know me, I’m a completely random guy, I mean I did take a class with Michael Littman if that means anything, but would you be interested in me coming in as a postdoc and working on this?” Jeremy was very friendly but I think that he probably felt like “who is this bozo?” But he ended up hiring me and that’s how my career in astronomy started. So, I owe a lot to Jeremy, and also to Dave Spergel and Mike Littman for my career in astronomy.

Those were very exciting years, because I was starting something that I’m not only passionate about from an intellectual point of view, but also connects to my emotional passions about astronomy and finding earthlike planets. It also aligns with my long-term vision for humanity, where we succeed in solving our problems on Earth and progress to become a multi-planetary species. The search for Earth-like planets brings the universe from something that is abstract, containing things that are pretty but don’t have to do with real-life in most people’s minds, to being filled with countless worlds that you can explore, as real as our Earth. And I think that is a fundamental cognitive shift for our entire civilization. Just like Mars and the Moon – in the past people thought about them as divine objects, maybe not even made out of the same matter as the Earth, but now we treat them as places we can go to and maybe make a home. That, of course, is still very challenging, but not impossible, and gives us something to look forward to as a species. And here is a part of astronomy that could similarly bring the rest of the universe into the realm of human existence in people’s minds.

So, with Kepler/K2 and other projects, Ames is probably one of NASA’s key centers for the search for habitable planets, so you made the leap to Ames after your postdoc?

After Princeton, I actually started another postdoc at Goddard. My wife (fiancé at the time), had a very prestigious AAAS fellowship at the State Department, so it was a fortuitous combination. But 5 months into my second postdoc, Ames gave me an offer I couldn’t refuse. At that time Pete Worden wanted to get Ames engaged into exoplanets, and specifically into direct imaging of exoplanets. The Kepler mission was getting close to launch and I think he saw the potential and the future of exoplanets beyond Kepler and wanted Ames to have a strong role in that, as a good Center Director would. He made the bet on direct imaging as being a big part of the search for exoplanets at NASA. Now, there are direct imaging missions that are being considered as flagships missions!

We usually ask about justifying the work you are doing in terms of the NASA mission and the taxpayers who fund it. You’ve already explained that your work in imaging exoplanets is closely tied to the search for life elsewhere in the universe and that is what humanity is thirsting for, to know whether we are alone in the universe.

Right, it’s a deep connection to age-old human questions and relevant to the entire human civilization. And I think it speaks to the human spirit, wondering what’s beyond the horizon.

So maybe just describe what the typical day is like for you and what you like most and least about your job.

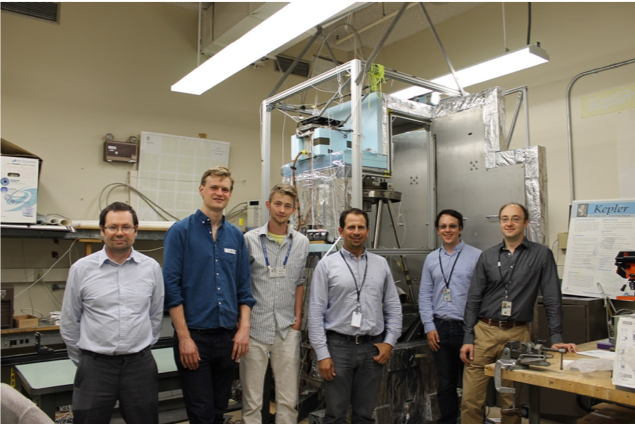

My typical day varies quite a bit, but as always work is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration, so a “typical day” will focus on the latter! Sometimes it’s me sitting at a computer and running simulations or writing reports or proposals, and a lot of it is interacting with the members of my group. Actually, some of my favorite activities during my day is brainstorming with Eduardo, Dan, Eugene, Thayne, and others, hashing out ideas in front of a board or looking at images and trying to see, “OK, what does this thing in this simulation mean? Or why is this performing this way and how do we make it better?” Or strategizing on the board, what is the best experiment we can do to advance our technology in the best way and to create the biggest value to NASA? Or writing equations and trying to figure out “how does this work on a technical level?” Part of the work is also doing optical experiments in the lab, and I really enjoy that as well, although these days, having to manage a group, that wedge of time has shrunk. But I really love just sitting in front of a computer in the lab and writing programs to control hardware. It is a lot of fun to control the laser or the deformable mirror that we have, testing our system, getting the data from our lab and getting actual images on the computer from the lab that tells us how well our system is performing, then figuring out how to advance it towards Earth-like planet imaging. And all the while, I’m thinking, I can’t believe I’m working on finding other Earths! Sometimes I have to pinch myself.

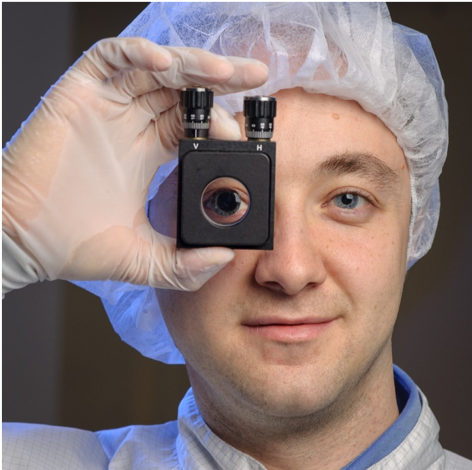

Can you tell us how the work you do in the lab is going to help us find exoplanets out there?

Before you put a planet-imaging instrument on a telescope, you have to develop and demonstrate the technology in the lab. The challenge is that stars are much brighter than planets (the Sun is 10 billion times brighter than the Earth!), so you have to figure out how to remove this starlight in your instrument without removing the planet. Our lab has been developing several techniques to do that. We have a laser light source, which simulates an image of a star as if it was delivered by a telescope into our instrument. We then pass that light through our instrument, take an image with our camera, and test: If this was a real system looking at the sky, would we see planets in those images or not? Initially we get an image that is “noisy”, with lots of remaining glare from the star that swamps the planet, but then we see what’s limiting it and how to remove the starlight further, understanding and modeling all the physics there, iterating on the design, making it better so that you can achieve the performance and see planets. We are also testing some of our technologies on a real telescope – the Subaru telescope in Hawaii, as well as a vacuum testbed at JPL. We do a little bit of observing with real telescopes, and we’ve had a program on the Gemini South telescope, using the Gemini Planet Imager to observe Alpha Centauri, which is the closest star system to us, to see if we can see any large planets there, or a disk.

Have there been any major findings or high points or something from your research, being that you are, well I don’t see any gray hairs so you must be a mid-career scientist!

Well, you don’t see gray hairs because there aren’t many hairs on my head! But I do have some gray hairs in my beard! (laughs)

Recognizing that major discoveries are few and far between.

There have been several times where the performance that we demonstrated in the lab was the best in the world or something that nobody else has done before. This included demonstrations at our lab at Ames as well as collaborations with JPL’s High Contrast Imaging Testbed, which is in a vacuum. The testbed we have at Ames is a “pathfinder” to develop technologies in the early stages, and the testbed at JPL is to test it further in a space-like environment. In both testbeds, we’ve achieved records, state of the art performance at several points in my career, both when I was at Princeton and when I was at Ames. It’s very exciting when that happens, when you see an image on your computer and you know it represents something that has never been achieved by anyone in the world, ever. With that image, you know that humanity has now advanced to the level where we can do this now, for the first time ever, and it enables science that was not possible before. While I was at Princeton, we demonstrated this with a so-called “shaped pupil coronagraph” that we tested on the JPL testbed. And at Ames, we’ve demonstrated that we could see a planet closer to a star than anyone else could see. Also, more recently, we demonstrated that we could see planets around binary star systems, stars that orbit each other, and no one else has done that either, so we’re very proud. However, I don’t want to make it seem like we are the only ones pushing the state of the art – there are several highly successful labs all over the world, each focusing on slightly different things, and together we are advancing the field as a whole.

If you weren’t doing this job, is there another that you would consider being your dream job?

Yes, probably, if I wasn’t doing this job, I would be working on technologies that would enable humanity to explore and colonize other planets, maybe like SpaceX. I admire what Elon Musk has been doing with SpaceX, where it paves the way to a bright future for humanity where we have hopefully solved the problems on Earth and are moving on to colonize and expand humanity’s presence to other worlds. I see what I’m doing as integral to that broad vision, where humanity grows out of its Earthly squabbles, and starts truly exploring the universe beyond, reaching for ambitious goals that rally the human spirit, just as Apollo 11 rallied the human spirit and for a brief moment, erased borders all over the world. By the way, some people believe that this type of thinking detracts from solving more pressing problems on Earth. I believe it is the opposite – exploring the universe and other planets helps us solve problems on Earth because it advances science, including planetary and Earth science. To truly understand the Earth, you need to understand other planets, just like a doctor needs to see many patients in order to be a good doctor for any one patient. Also, a lot of the scientists and engineers who are working hard to solve the world’s problems today cite Apollo 11 as the reason they went into STEM. Space exploration has the power to inspire the next generation of STEM leaders, which is what we need to take care of our Earth.

What advice would you give to a young student who would like to have a career as you have?

Number one is you have to make sure you’ve got the STEM fundamentals down. Focus on the STEM fundamentals, because when you have a deep understanding of the math and the physics concepts, that sets you up for anything, in whatever field you want to go into. Also, it enables you to see things at a deeper level and recognize potential breakthroughs much more efficiently and much quicker than somebody who is just looking at things from a purely practical point of view. That’s how major discoveries get made. You realize that something has enormous potential from a fundamental physics point of view, whereas somebody who thinks purely in practical terms will dismiss the idea because it is not yet practical.

Number two is to make sure you do something that you’re really passionate about. It sounds like a cliché, but do a lot of introspection about what it is you like to do. When your courses are done, what is it you do with most of your free time? I think that if you can identify something within that that leads to a career, that’s where you should go. Don’t try to follow what’s “hot” at the moment, but follow where your passions are and what you already spend most of your free time on.

And that’s related to the follow-up question: what do you do for fun?

One thing obviously is amateur astronomy. That may seem like not a very good answer to your question, but . . .

That’s OK, it’s what you do for fun. We’ve had good answers that are all over the map.

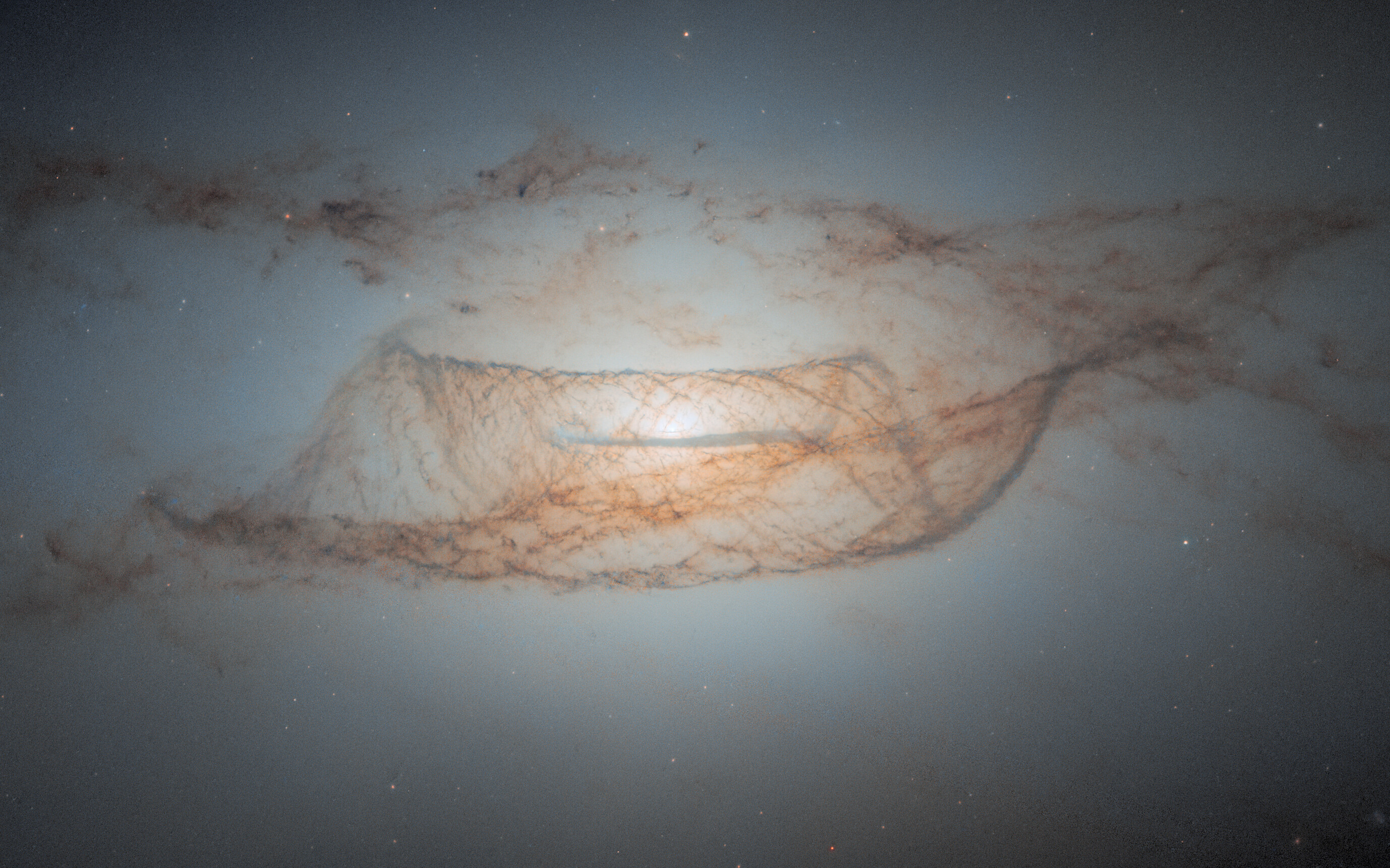

Well, I have a 10-inch telescope and I love using it to observe the sky and take images. I have some images I’ve taken at home if you’d like to see them. I also like playing space-themed board games, especially with my kids, but with members of my team as well. There are some surprisingly good and educational science games out there.

Do you mean board games? Not video games?

No, no, board games. They are much more interactive. Believe it or not, there are fun games that model real physics, where real physics equations and concepts like delta-V are distilled into a relatively simple set of rules. At that point it becomes more of a simulation — for example, how do you fly to Mars and what delta-V does it take to get there and how much fuel will you need to take and what efficiency rocket, and so on. It’s very nerdy, but those are some of my favorite things. I also love rollerblading and spending time with the kids in general.

Skateboarding?

Have not tried skateboarding, but I love biking, rollerblading, and skiing.

How many kids do you have?

I have two kids, a 5-year-old and a 9-year-old.

And is there an accomplishment you’re most proud of that’s not related to your work?

My first instinct is to say, my kids!

I would think so!

But that might be a little bit too cliché.

No, you do things with them and enjoy life with them and help guide them, that would be my proudest accomplishment.

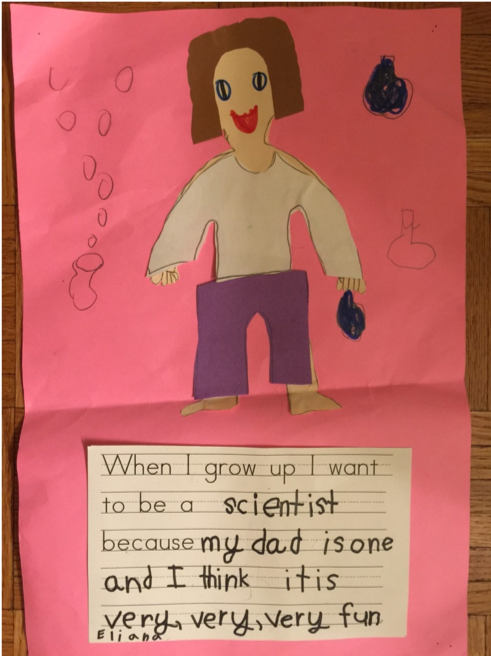

My relationship with my kids and my family is something that I’m very proud of, and I hope it continues the way it is right now. One of my proudest moments as a dad was when my 9-year-old daughter, Eliana, who I think was 5 at the time, brought back a drawing from school and it said “when I grow up I want to be a scientist because my dad is one and I think it is very, very, very fun”. Now to be fair, she’s not sure if she wants to be a scientist anymore, she is finding other passions. But I’m trying to encourage whatever she feels passionate about, and as long as she does something that she is willing to work hard at and is fulfilling, that is what matters to me.

Do you have any pets, by the way?

We’ve got two parakeets. That is again my daughter’s doing. We’ve had them for a few years now, although we’re not really big “pet” people.

Who or what inspires you?

What inspires me the most is the achievements and advancements of our civilization.

You’ve mentioned that a time or two already, that humanity is at this point and is going forward and doing these wonderful things.

Yes, I feel a connection to humanity as a whole race and it’s really inspiring to see how our civilization has achieved what it has achieved, even in the face of the challenges we face today. The most inspiring thing to me is to see human civilization achieve major milestones that make us better and to be a part of it.

You are an optimist!

There are certainly things that we have done what we can’t be proud of, but we’ve cured tons of diseases, landed on the Moon, we’ve found thousands of planets, we’re talking about going to Mars and finding earthlike planets, we’re talking about finding life, and we’ve managed to not kill ourselves – so far. If we are lucky enough to find a civilization with whom we can have a meaningful conversation, I’d like to think that we can be proud of ourselves in spite of these other things, and be proud of what we have accomplished.

The people who inspire me the most are the ones who have enabled these key advancements of our civilization. A lot of them are scientists, like Newton, Einstein, because they have advanced human knowledge, human science and human understanding of the place we live in. Explorers are also some of my idols — for example, Elon Musk, whose vision for humanity’s expansion and becoming an interplanetary species is similar to mine. That vision inspires me a lot — the idea of having a colony on Mars is something I find incredibly compelling and inspiring.

Would you like to be a member of a colony on Mars? Or would it depend on whether it’s a one-way trip or not?

Absolutely, but it depends on what I would do there. I want to be able to contribute as much value as I can in areas where I have the most skill. And if I can do that from Mars without sacrificing my family, then I would totally be up for it, even on a one-way trip.

And then we ask if there is a favorite space image.

There’s one I have that’s very clear in my mind.

Is it the one of Elon Musk’s red car sailing through space?

No, not that one. That one is fun, it might be my favorite “fun” image, but my favorite serious image, the one that speaks the most to me, is something called the pale blue dot, which was an image taken of our Earth by the Voyager spacecraft in 1990 as it was leaving the solar system. Because the Earth was so far away, the image appears as a little blue pixel on a noisy background. It was taken at the suggestion of Carl Sagan, who later said something like the following about this image: “imagine everyone who has ever lived, and everyone you’re ever known and loved, and all the wars and all human accomplishments. All of these, and the entirety of human civilization are all contained in that one pixel, a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam”. To me, that is a very powerful image that really brings out that overview effect that I talked about earlier. I feel that if more people could see our Earth that way, then I think people would do fewer things to be ashamed of and more things to be proud of.

A mote of dust, suspended in a sunbeam

– Carl Sagan

And if there’s a favorite quote.

“Exploration is in our nature. We began as wanderers, and we are wanderers still. We have lingered long enough on the shores of the cosmic ocean. We are ready at last to set sail for the stars.” – Carl Sagan

We don’t want to end on a negative note, but when we asked you what you liked best and least about your job, we never heard what you liked the least.

Oh, paperwork, no question.

I think we’re at 100% on that one.

But it’s a necessary evil. Without a certain measure of bureaucracy, things start to fall apart.

I would say it’s a necessary element.

Yes, I probably overstated it. But that’s why I think that people like you guys are so amazing because you enable scientists to do science with a minimum amount of paperwork. You and Lawrence help me enormously with my group’s budget, and in general, the administrative personnel in our division deserves more credit!

Would you like to share anything about your reading interests or what kind of music appeals to you?

Well, I play the piano. Not very well but enough for it to be fun, for myself. My favorite piece, by far, is Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata. My favorite book? I would say my favorite fiction book is “War and Peace” by Tolstoy. I found it to be very deep but also a page-turner for me. Not like boring books you study in school. It had some key insights into human nature that kind of influenced my thinking about humanity. I really like Carl Sagan’s “Contact”, which is also a fiction book. I guess my favorite science fiction book is probably a tie between “2001, A Space Odyssey” and “Contact”.

Thank you.

Interview conducted by Fred and Sara on April 3, 2019