In December 2019, Mr. Michael Aguilar retired from the NESC. As the NASA Technical Fellow for Software, he led assessments for about 15 years, helping programs and projects with challenging problems involving software, hardware, and their complex interactions. For Mr. Aguilar, each new problem was like solving a puzzle, one with hundreds of lines of code and no edge pieces to build on. Fortunately for Mr. Aguilar, solving puzzles was something he had been doing his entire career.

One of Mr. Aguilar’s first phone calls at the NESC was from code developers with the Hubble Space Telescope Program. “I had no idea about Hubble, but Goddard had put a team together and asked for my help,” he said. Software code in Hubble’s brain needed to be fixed, but first it had to be downloaded from its location in space, so Mr. Aguilar helped them find a way to download the code and troubleshoot it.

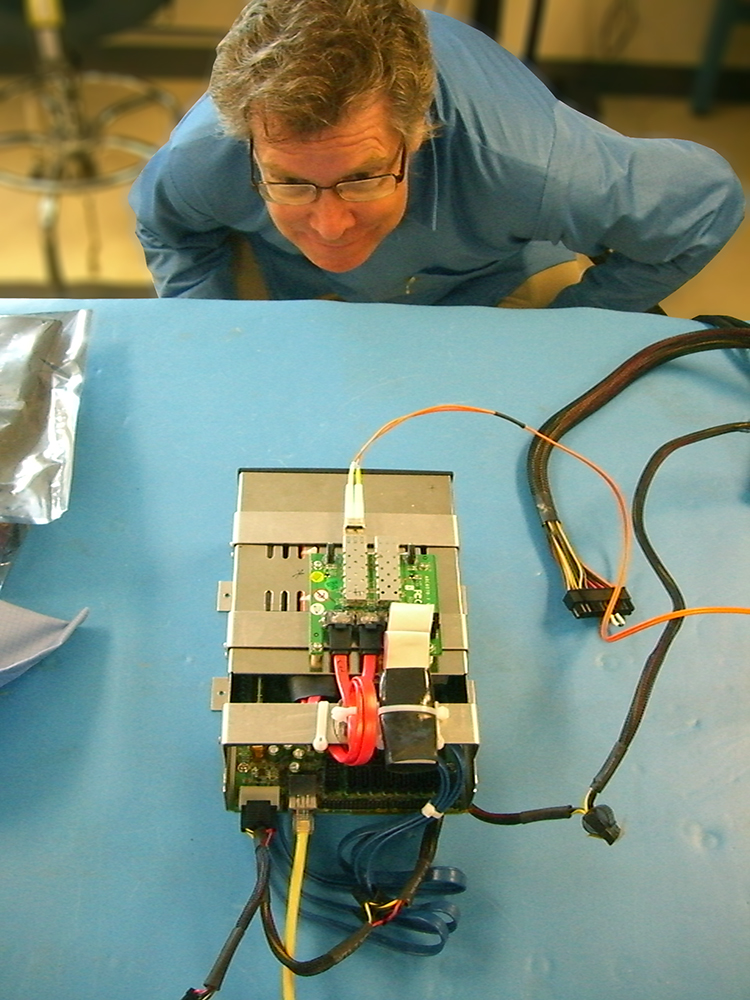

With that assessment, Mr. Aguilar realized what the role of software technical fellow would require – “troubleshooting computers that are deeply embedded inside hardware, where you don’t have a screen and keyboard, and bringing the data out and doing the fix with what you have,” he said. “And troubleshooting and correcting a software you didn’t write, that you didn’t understand, and in many cases, was already in space.” Luckily for the NESC, the unique skill set Mr. Aguilar had acquired over several decades in industry and government had prepared him well for the job.

“Early on I knew I wanted to be an engineer. That was all I wanted to do.” In fact, his family clued in to his passion early on as he took apart anything mechanical laying around the house. To earn enough money to send himself to college, he worked as a truck driver for a few years right out of high school. With the money he saved, he was able to attend a two-year technical college that had its own computers and was teaching computer maintenance. “This was a couple of years removed from punch cards,” he said, “where you go in at night and run your deck of cards through the computer and come back for an answer the next day.”

With electronic and computer technology degrees in hand and on recommendation from his college instructors, Mr. Aguilar applied for and landed a job with Continental Airlines, working on their newly-acquired pilot-training flight simulator for the DC-10 aircraft. His task was to learn how it worked and then ensure it kept running.

It was a dream job for him. “We had a lab with all of this specialized test equipment. It was wonderful,” he said. He learned the DC-10 inside and out, learning how to fly the aircraft and developing his own equipment for trouble shooting problems. If a pilot was having issues, Mr. Aguilar flew in the co-pilot seat as a diagnostician of sorts, listening to sounds and feeling odd vibrations so he could figure out what was wrong and find a solution to fix it. The job took him all over the world, from Hawaii to New Zealand and everywhere in between. He became so versed in the flight simulator’s computer systems and programming that the developer began calling him for troubleshooting advice.

After 17 years, however, Mr. Aguilar felt he’d reached a ceiling with his two technology degrees and decided it was time to move on. He moved to Belgium where he’d been selected to program the computer and build the curriculum for teaching the maintenance of the emergency communications system at NATO headquarters. During his nearly three-year stint, he witnessed the collapse of the Soviet Union and the tearing down of the Berlin wall. He still has a shoebox at home filled with pieces of that historical moment.

While abroad, he managed to save enough money to attend the University of California at Northridge when he returned to the states. He had just received his acceptance letter when the Northridge earthquake took out the school’s campus, including its robotics labs. So, the school hired him to put those labs back together again. A scholarship to Carnegie Melon followed, where he earned master’s degrees in computer and software engineering.

He then went to work for a small company in Washington D.C. called Software Technology Inc. (STI) where he helped build satellite networks. At that time, STI was working with NASA on the second International Space Station module. The USSR was originally tasked to build the module, which would contain the fuel, engines, and thrusters needed to keep the first module in orbit. The deadline for launch was tight, and the Soviet Union was struggling in the aftermath of their collapse, so NASA asked STI to help.

“I started building a spacecraft starting with whatever was available at the Naval Research Lab. It was extraordinary,” said Mr. Aguilar. “We got it finished and ready for launch in a short amount of time.” Their Soviet counterparts did manage to finish their module in time, and it was launched in lieu of what was then called the Interim Control Module. “But, NASA loved what we did. I’d never been in a group that felt that way about what we were building. It was a great success.”

After STI, Mr. Aguilar worked with the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) building robots for the military, a remote controlled car outfitted with night vision that would help soldiers maneuver in tunnels and caves. He spent his nights driving his robot around replica villages at Quantico with the special forces.

Then NASA Goddard came calling. They knew about his work with STI and needed someone willing to travel around Europe to help select the contractors who would build the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). “I spent a year traveling through Europe and Canada, going to meetings and judging how well their development was and whether we should use them.” He was the manager for JWST Instruments and their integration when the NASA Tech Fellow job became available.

His first few weeks at the NESC were quiet. He found that most code developers weren’t in the habit of sharing their software, preferring to keep close hold on their data, much of what was proprietary. When he finally had the chance to prove himself with the Hubble Program, his phone starting ringing. He was called in by NASA Programs like the Space Launch System and the Orion Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle, even Toyota, to review code, perform verification and validation, troubleshoot both software and hardware issues, and in some cases, develop new code.

One of his most memorable assessments was the NESC-designed alternate launch abort system for the crew exploration vehicle, called MLAS. He wrote the testbed and operational software. It was one of his first opportunities to collaborate with fellow NESC members and tech fellows. He and his technical discipline team also tackled the huge job of reverse engineering software code for a major car company when they tried to help uncover issues without infringing on their proprietary information.

One of his last assessments before retirement was helping to verify that a commercial provider’s Autonomous Flight Termination System met critical software standards and best practices prior to crewed flight.

Aside from having spaceship wallpaper as a kid, Mr. Aguilar said working at NASA wasn’t part of any grand master plan. In fact, most of the jobs he held during his career were the result of just being in the right place at the right time. His road to NASA was winding and unpredicted, but he is happy with the end result. “I think my career was never really about computers and spaceflight. If you boil everything off, my passion was puzzles, troubleshooting what was wrong and figuring out how it worked,” he said as his retirement date neared.

“I think it’s finally time for me to find puzzles with a little less stress and a view of the ocean.”