Young Luke and Leia are facing an uphill struggle for survival. The odds are against them.

The siblings aren’t lightsaber-wielding rebels, and their enemies have nothing to do with a power-hungry empire. Luke and Leia are newly hatched American alligators. Their top priority in the next few years is avoiding deadly encounters with the wild hogs, raccoons, larger gators and other predators in the wilderness around NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

Luke and Leia hatched Aug. 21 within the safe confines of an incubator near the spaceport’s famous launch complex. Throughout the summer, as the tiny reptiles developed in their eggs, they were unwitting but active participants in an ongoing study of alligator nests at Kennedy.

“It boils down to this: Genetically, humans, alligators and other animals have many similarities,” explained Lynne Phillips, a NASA physical scientist in Kennedy’s Environmental Management branch. She oversees Kennedy’s Ecological Program, which manages several wildlife research programs at the spaceport, including alligator studies.

“Our endocrine systems are nearly identical. If there is an impact to alligators’ endocrine system, we can relate it directly to human health.”

Alligators are “apex predators,” meaning they’re at the top of the food chain at Kennedy. This makes them one of the proverbial canaries in the environmental coalmine here in central Florida. Researchers study alligators at Kennedy and across the sunshine state because at each stage of life, the animals provide vital clues about the health of the local ecosystem and shed light on the physiological effects of an unhealthy environment.

Luke and Leia are just two out of several nests of baby alligators hatched in 2015. They served as this season’s sentinels.

Kennedy Space Center is well-known as the nation’s flagship launch site, a starting point for missions of discovery and a testbed for new technologies. But the spaceport also shares boundaries with the 140,000-acre Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge, managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. And while the refuge’s diverse array of ecosystems provide sanctuary for hundreds of species, it offers biologists an ideal location to monitor how our planet is changing and learn how these changes impact those who live in it.

There are national requirements for protecting the environment and endangered species, including the National Environmental Policy Act and Endangered Species Act. But Kennedy’s wildlife studies are about more than that, Phillips said.

“NASA has its own self-imposed sustainability and environmental requirements. We are very invested in sustaining our environment here on Earth,” she explained.

“We want to be leaders in environmental stewardship.”

Kennedy’s Ecological Program began studying alligators in 2006. The spaceport’s unique location and isolated alligator population provided a good reference site for alligator studies already underway in Florida. The program was set up with the help of Dr. Louis Guillette, a world-renowned biologist with the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. Guillette, a co-investigator, contributed time and expertise in studying the impacts of environmental contamination on wildlife and regularly collaborated with the Kennedy team until his death Aug. 6, 2015.

“Lou was instrumental in starting this program,” said Russ Lowers, a wildlife biologist with InoMedic Health Applications (IHA) at Kennedy. “He rewrote the book on eco-toxicology; his knowledge has been spread around the world. His legacy will live on.”

The research is a collaborative effort. The Ecological Program partners with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, the Medical University of South Carolina and the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources, but there also are contributing team members across the U.S., as well as Central America, Africa and Japan.

Alligators Provide Clues about Environmental Health

Endocrine disrupting contaminants such as organic compounds and heavy metals can have a dramatic effect on the fertility and reproductive development of the population. Research has shown that adult male alligators in contaminated surroundings have significantly higher levels of contaminants in their bodies than adult females – because the contaminants in females are offloaded into their eggs.

But what does that do to the developing embryos, and ultimately, the alligator population as a whole? And what about the effects of rising temperatures with climate change? Incubation temperatures determine whether babies develop into males or females.

Monitoring the development and hatch rates of gator embryos and tracking temperatures at nests across the refuge will help find answers to these questions, according to IHA wildlife biologist Stephanie Weiss.

“The nesting research tells us the reproductive health of the population here,” Weiss said.

This season alone, the team collected 352 eggs for the study, and many are still in the process of hatching out. More than 2,600 eggs have been collected since the program’s inception, with an overall hatch rate of 77 percent.

“Studying large animals will give you the toxicology results dating farther back,” Lowers added. With the nesting research, he pointed out, “we’re going back to where they start, as eggs.”

No one knows how many alligators call the refuge home. But for about two weeks at the end of every June, adult females get to work building nests out of marsh grasses, cattails or other nearby materials in order to launch a new generation of gators.

Nesting Season Begins

Temperatures hovered around 90 degrees Fahrenheit as the sun rose on June 24. Despite the sweltering heat and humidity, the research team headed out in pickup trucks to a freshwater marsh about a mile and a half northwest of the spaceport’s Vehicle Assembly Building.

Nesting gators build their nests in hard-to-reach places, but team members knew where they were going. They’d spotted the nest during a survey flight aboard a NASA helicopter.

“The helicopter is the number one most important tool in our tool chest for finding alligator eggs,” Lowers said. “These moms tend to put their nests far away from public access.”

Adult females at Kennedy reproduce every three years or so, laying a clutch of 30 to 40 eggs in late June. Researchers hope to find 20 nests per season, Weiss said, but it varies from year to year.

“Typically, we don’t find that many nests out here,” she explained, “but this was a good year.”

Biologists have to trek through marsh grass and muck to reach the nest. The mother alligator usually isn’t home when the team shows up. Nine times out of 10, she’s out and about, only checking her nest periodically. But sometimes, she’s right there.

“If Mom is there, you have somebody watch her, but she’s usually pretty docile. She’ll hiss at you, but she’ll usually stay back,” Lowers said.

“If she doesn’t want you anywhere near there, she tells you. And in that case, we’ll capture her and pull her to the side. We put her in a little timeout for a minute, and then let her go.”

The first 10 nests were outfitted with tiny, wireless sensors, called thermistors, which are programmed to log the current temperature every five minutes throughout the nesting cycle, typically about 60 days. Temperatures above 31.5 degrees Celsius (about 89 degrees Fahrenheit) result in more males; temperatures below that level produce more females. Biologists want to track these temperatures year after year in order to watch for trends and monitor the balance of males to females. This data is compiled at the end of the season, after the nest is hatched out and the sensors can be collected.

Only one team member approaches these nests, first covering up with water and mud in an effort to prevent area predators from associating humans’ scent with the presence of eggs. Thermistors are carefully inserted in the nest beside the egg cavity at three different depths – the bottom, middle and top – as well as in a nearby tree. Most of the eggs are left in place; a few are collected and brought back to the laboratory.

At other nests, all eggs were removed. Such was the case for Luke and Leia. Their mother helpfully had constructed her nest at the base of a tree just a few steps from a dirt road.

The team used a thermistor to check the temperature inside the nest, then measured its width and height, as well as the depth of the egg cavity inside. Finally, they pulled the eggs out one by one, drawing a line on the top of each to mark its orientation – a rudimentary “This Side Up.”

“When we pull an egg out, we can’t tilt it, turn it or shake it. If we do, we’ll kill that egg,” Lowers explained.

The eggs were carefully placed in a bin lined with nest materials. Then they, too, were driven to the lab.

Into the Incubator

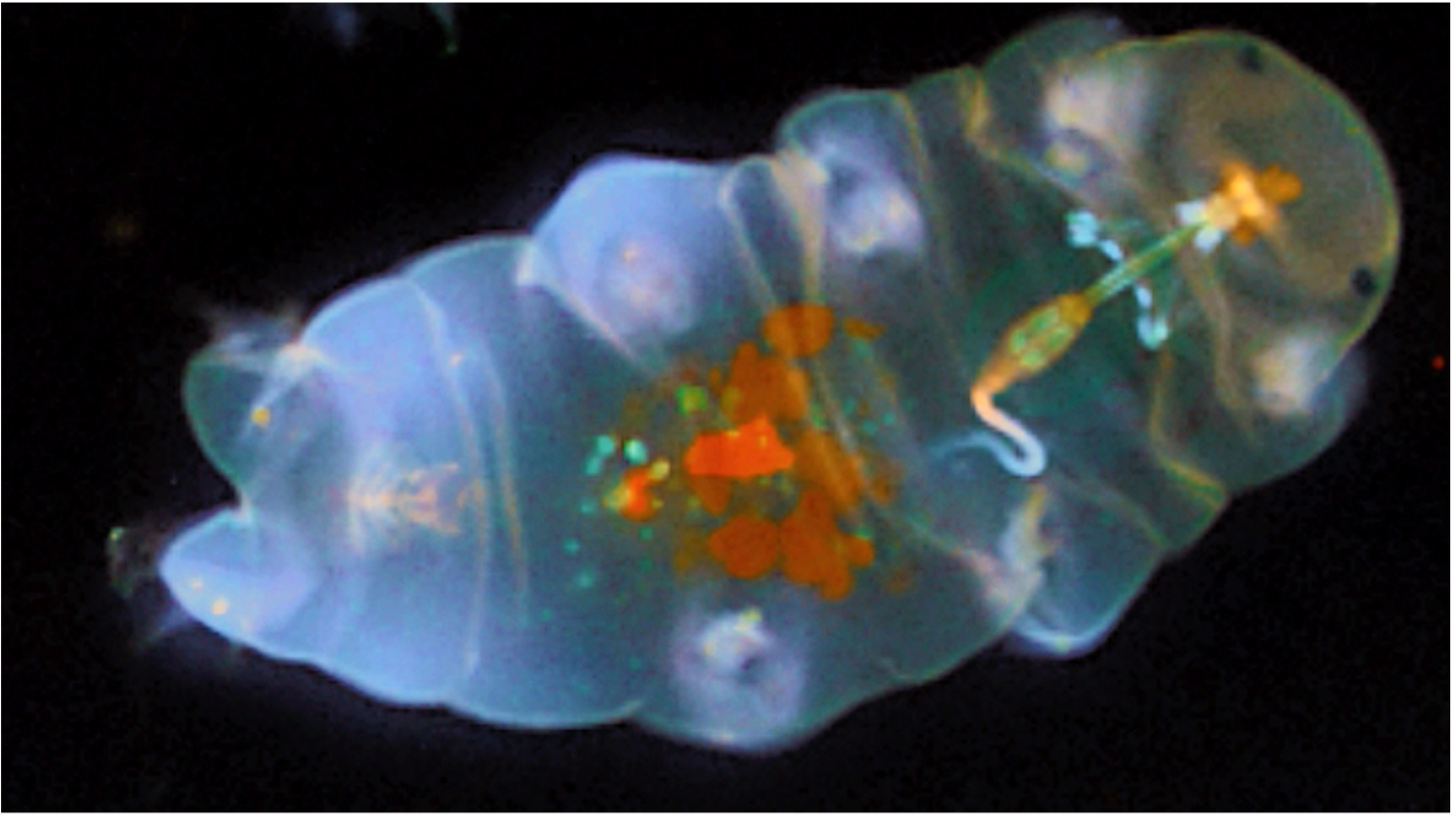

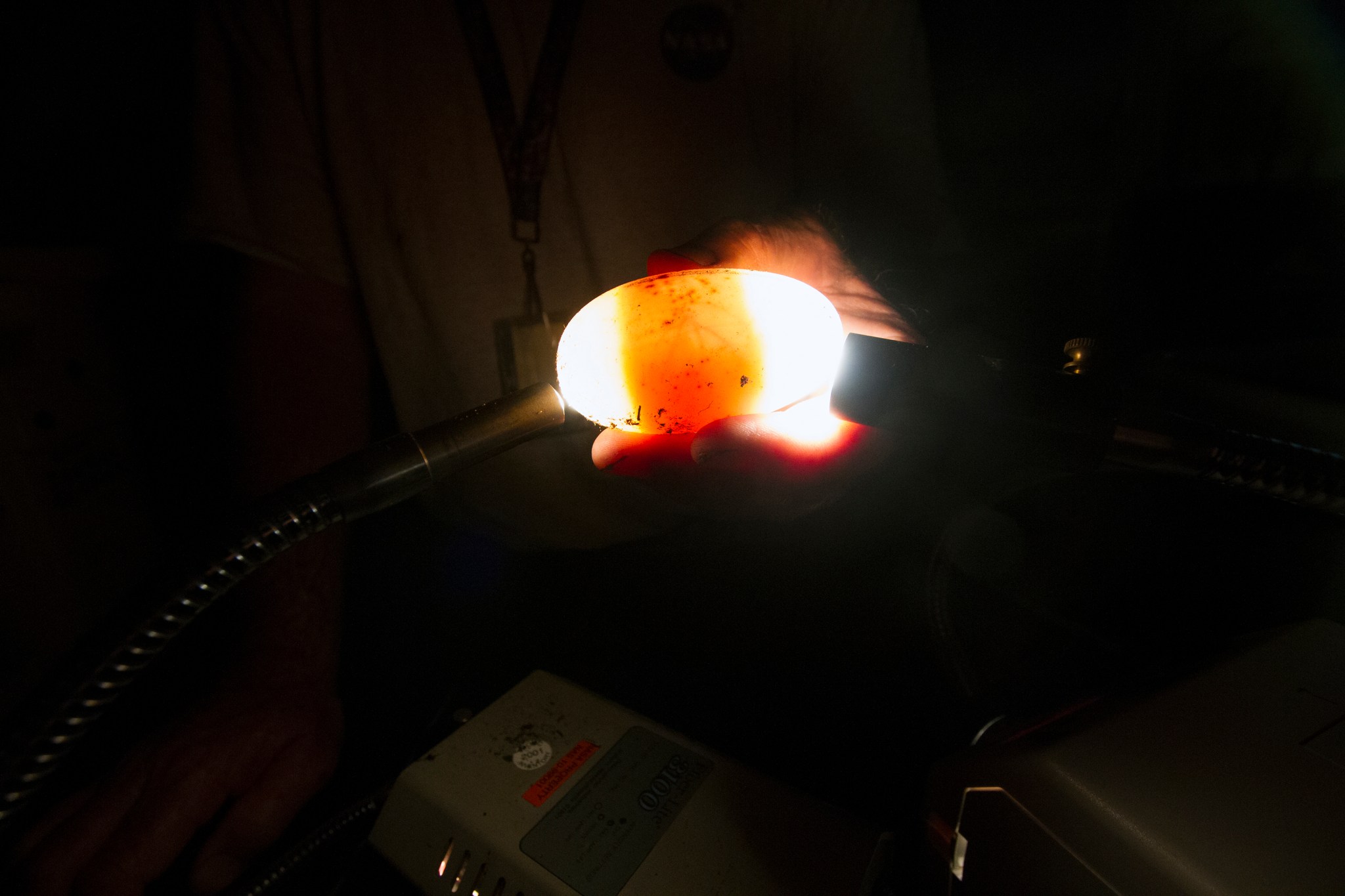

Luke and Leia finally got their names when they arrived at “the shed,” a facility that includes the Ecological Program’s wildlife laboratory. Lowers and Weiss shined a bright light into one end of each egg, a process called “candling.” Viable eggs revealed a dark-banded center.

One egg from every nest – including the eggs removed from the thermistor nests – was opened up in order to determine the gestational age of the embryo, which in turn told the researchers when the eggs were deposited and roughly when they would hatch.

Each clutch was placed into a bin lined with sterile sphagnum moss to cradle the eggs and keep them moist. Then the bins went into the incubator, set to a steady 31.5 degrees Celcius.

And then the biologists waited and watched for nearly two months.

On Aug. 21, Luke and Leia made their debut, chirping loudly as they pushed their way out of their shells.

Their siblings began to pop out one by one, encouraged by the noises of the hatchlings around them. It can take up to a week for a clutch to completely hatch out.

Of the 33 eggs collected from that nest, 24 hatched.

“They come out very feisty, too,” Weiss said. “They bite onto each other and start rolling.”

The last of Luke and Leia’s siblings emerged on Aug. 26. At barely 10 inches long, the babies were ready to start their lives in the wild.

Reptilian Reunion

Two days later, Lowers loaded the newly hatched gators from Luke and Leia’s nest into a shallow container with just a little water. He carried the lidded bin outside to a waiting pickup truck.

It was the alligators’ first time seeing sunlight or smelling outdoor air.

A little more than two months had passed since Phillips, Lowers and Weiss first had visited the nest to collect the eggs. Lowers took the lid off the bin and tipped it, gently emptying the babies onto the soft grass atop the nest.

Their mother was nowhere in sight, but they called out for her, several of them making their way down the side of the nest toward the water a few feet away.

“Mom will hear them and come greet them just as she would if they had hatched out of the nest,” Lowers said.

“Alligators are kind of unique with the maternal instincts they have,” Weiss said. “They will defend the nest, and they will defend the babies for a year or two. In the reptile world, that is unusual.”

Even with the guidance of an attentive mother, less than one percent of baby alligators make it through their first four years.

This means Luke and Leia have their work – to reach adulthood – cut out for them. But one glance across almost any body of water at the spaceport reveals multiple grown gators, their spiny backs barely breaking the surface as they slowly cruise around.

Clearly, even with the odds stacked against them, many little ones manage to survive.