By Jason Costa

NASA’s Kennedy Space Center

NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida recently published its Indian River Lagoon Health Initiative Plan, which establishes a clear framework for Kennedy and its partners to ensure the health of the waterway in and around the spaceport. A large part of the plan calls for increased monitoring of marine plants and animals. By studying seagrass distribution and manatee populations in the lagoon, Kennedy’s ecologists are getting a much clearer picture of a waterbody in distress.

“Environmental stewardship is important to us as a center, it’s important to us as an agency,” said Don Dankert, environmental biologist in the Environmental Management Branch. “The lagoon health plan is one more testament to our 30-plus-year history of ecological monitoring and understanding how we can operate and grow this spaceport and still be responsible stewards of these amazing natural resources that we have here on center.”

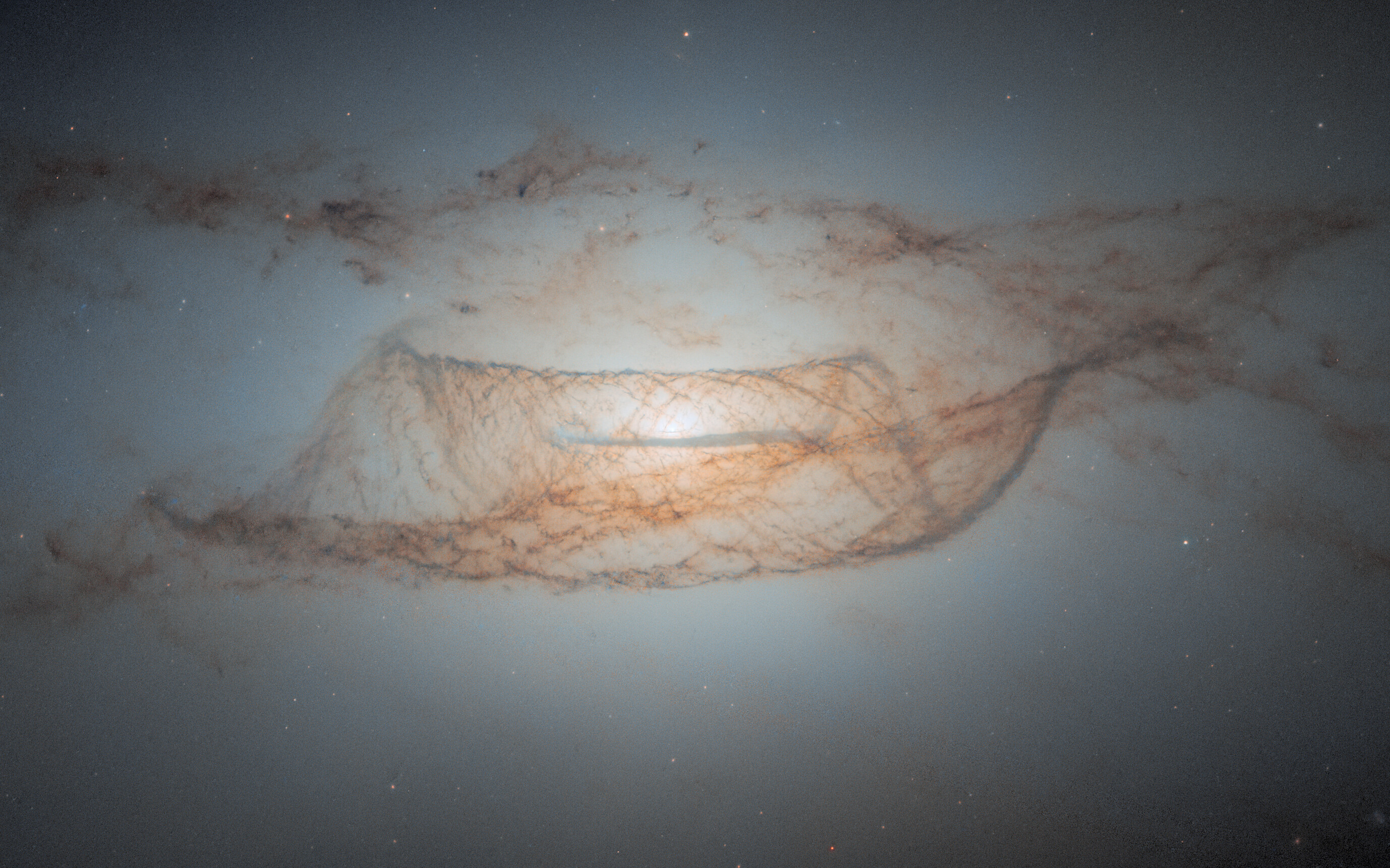

The Indian River Lagoon – which is not a river, but a shallow-water estuary – extends 156 miles along the Florida coast from Volusia County to Palm Beach County. It is considered one of the most biodiverse lagoon ecosystems in the Northern Hemisphere, home to more than 3,000 species of plants and animals.

Years of development along Florida’s East Coast have affected the health of the waterway. Recent studies show the water of all three lagoon basins comprising the estuary – the Indian, Banana River, and Mosquito lagoons – are impaired by eutrophication, or excessive nutrients. Over the past decade, this has contributed to repeated algal blooms that have decimated seagrass distribution in the estuary.

“Anyone comparing Google Earth images taken before the seagrasses declined can see the darker patches of vegetation that were large expansive beds of seagrasses,” said Doug Scheidt, who works for the environmental branch under NASA Kennedy’s Environmental and Medical Contract. “We’ve been performing annual sampling to track seagrass distribution since 1983, and it appeared to stay in good shape until around 2010-2011, when the lagoon was in obvious collapse in more and more locations. The following year is when the bad water quality algal blooms became consistent around Kennedy.”

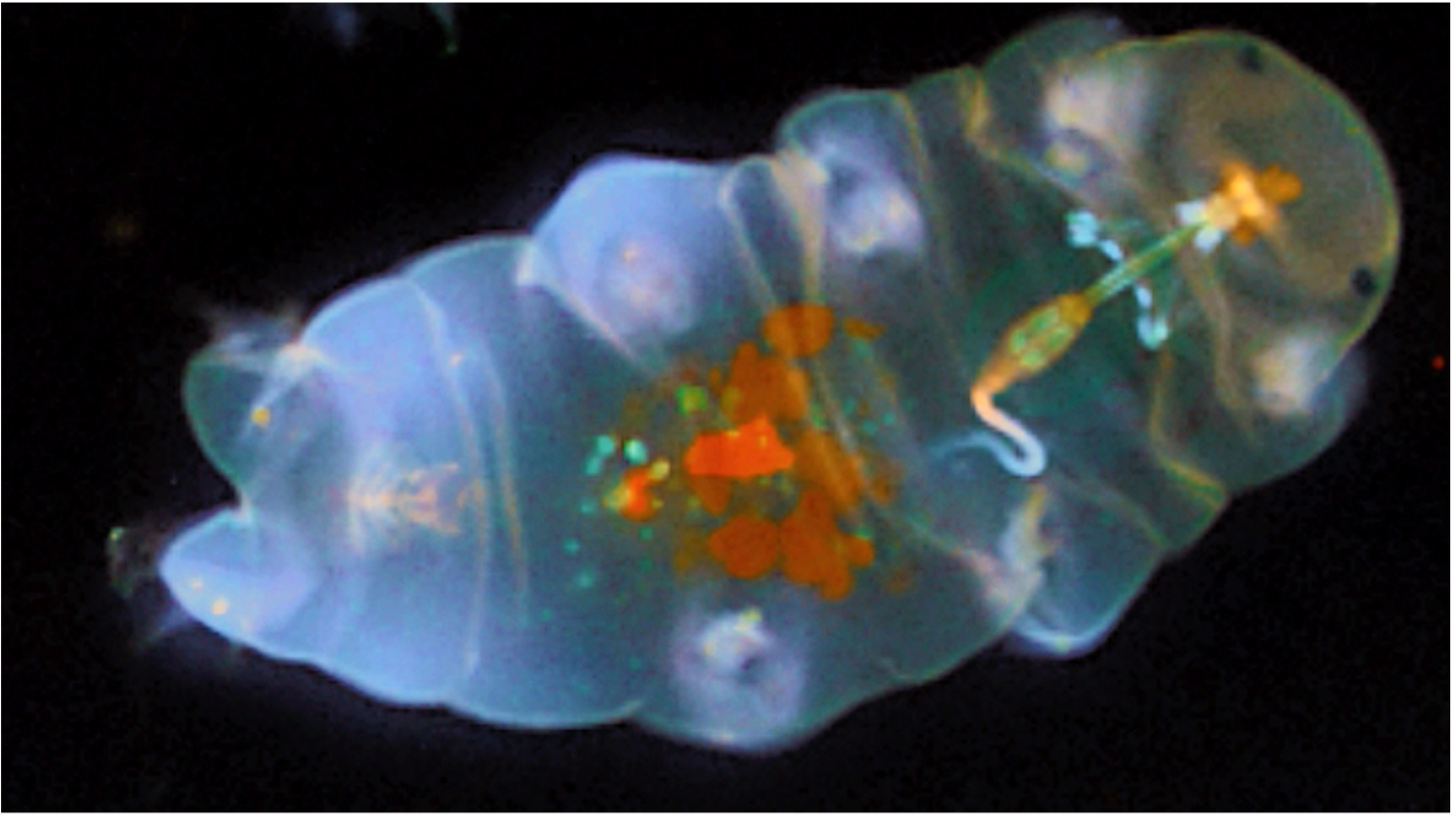

The repeated and intense algal blooms over the past decade stifled seagrass quantity and diversity in the lagoon, which normally includes several different varieties. The seagrass improves water quality by reducing nutrient pollution and trapping sediment while also providing manatees and other marine life with a habitat and an important food source. Manatees, sometimes called sea cows, must consume 100 pounds of sea grass each per day, and their population in the lagoon has been dramatically impacted as the sea grass declined.

Ecologist Jane Provancha, manager of the ecological monitoring team at Kennedy, has been studying the health of the lagoon for nearly 40 years. She has seen firsthand NASA’s efforts to monitor and ensure the health of manatees around the spaceport – even retrofitting booster recovery boats in the 1980s with jet drives to prevent potential propeller injuries in the spaceport’s waterways where the large aquatic mammals congregate.

“NASA took the initiative to map out seagrass distribution and then compared where the manatees were by using helicopters with biologists aboard to count animals,” Provancha said. “Even as other parts of the Indian River Lagoon system were slowly declining – mostly because of unfettered development pressures – Kennedy remained a quiet, seemingly resilient sanctuary.”

Around 1990, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and NASA agreed to close public boating and commercial fishing in the southern Banana River portion of Kennedy Space Center to offer more quiet waters for endangered manatees. While the spaceport is situated on 140,000 acres of federally protected land, water, and marshes, the counties around the estuary have grown tremendously over the past three decades to support a population that nearly doubled in that time. Measuring the impacts from increased stormwater and wastewater inputs, dredging, and overfishing outside Kennedy creates a sharp contrast to the ecological conditions within boundaries of the spaceport.

“A lot of the original NASA monitoring programs were set up to compare the less developed Kennedy to other more developed areas of the lagoon,” Scheidt said. “Only around 6% of the space center’s footprint has any impact on the natural land – and as growth encroached around Kennedy, its lagoons became even more important as a refuge for manatees, with better water quality than other areas.”

Municipalities, county, state, and federal entities are making efforts lagoonwide to reduce and remove sediment, nutrients, and other pollutants from stormwater that drains into the estuary, with hopes of improving overall water quality. But restoring the health of the lagoon is a complex situation with no easy or quick fixes.

“Monitoring doesn’t fix the problems, but we can keep track of the health of the lagoon system’s flora and fauna,” Provancha said. “We’ve seen that the waters are clearing somewhat and we’re seeing increases in vegetation, particularly with some rooted algae that can help stabilize the bottom and lay a path for seagrass. And the manatees still visiting Kennedy – who survived the last few very difficult years – may tell us by their movements where new seagrass is growing.”

Provancha and her colleagues remain hopeful that their monitoring efforts will support NASA and others searching for the next right steps.

“It may take years and considerable coordinated effort for the lagoon to recover,” Provancha said. “But our monitoring helps inform NASA and other agencies – local, county, state, and federal – as well as residents attempting to make improvements and reduce impacts to ensure a healthy, stable lagoon ecosystem.”