A remotely piloted solar aircraft has demonstrated it can hover in the stratosphere to provide cellular networks in isolated areas. It also demonstrated remote sensing and observation capabilities.

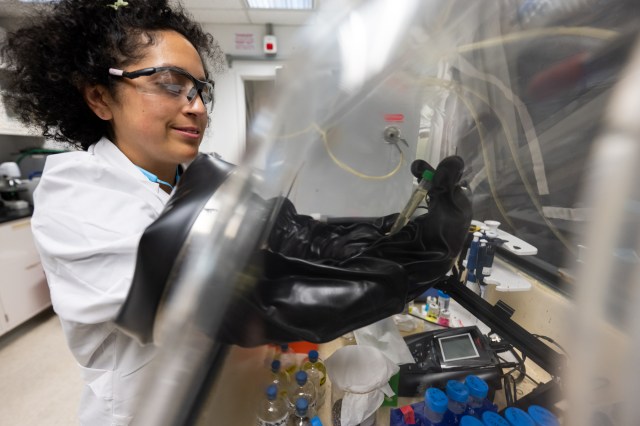

That aircraft is the Sunglider. AeroVironment Inc. of Simi Valley, California, has a long history of working with NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California. The two groups have collaborated in efforts to complete preliminary flight tests to prepare for reaching ever more complex goals with solar powered aircraft. Sunglider is a result of HAPS Mobile Inc., which is a subsidiary of Softbank Corp. and minority-owned by AeroVironment.

AeroVironment has been working on solar aircraft for more than 40 years. The solar powered and human piloted Gossamer Penguin flew on July 25, 1980, from Roger’s Dry Lakebed near Armstrong. During the next four decades the company’s remotely piloted family of solar-powered aircraft made ever higher altitude flights and capability demonstrations. The Helios Prototype reached a record altitude for a propeller-driven vehicle of 96,863 feet on Aug. 13, 2001, beating a previous record set by the company.

Many of AeroVironment’s solar powered aircraft such as the Pathfinder, Pathfinder-Plus, Centurion and Helios flew as part of NASA’s Environmental Research and Sensor Technology program managed at Armstrong. An initial goal of that program was to develop science instruments for studying the stratosphere. Another focus became development and demonstration of technology for enabling a new class of aircraft capable of flying the high altitude, long duration Earth science and environmental missions.

Adding to the legacy

The Sunglider follows in the traditions of AeroVironment’s history in solar remotely piloted aircraft, but is considered a high-altitude, platform system, or HAPS vehicle. It is with Sunglider that the company flew to 62,500 feet for more than five hours during a 20 hour mission on Sept. 21, 2020. Solar batteries power the aircraft during the day and collect and store energy for use at night.

The Sunglider is very long with a wingspan of 262 feet. For comparison, a Boeing 747 has a wingspan of about 229 feet. It also has 10 electric motors that propel the aircraft at about 40 mph.

“Sunglider’s motor technology has advanced through multiple generations of improvement since the Pathfinder-Plus and the Helios Prototype,” said Peter De Baets, AeroVironment senior director. “As a result, we have an increase in efficiency and capability. As an example, Helios was a much lighter aircraft and needed 14 motors. Sunglider only needs 10. That gives you an idea of how much more capable today’s materials and technologies are.”

The September mission based at Spaceport America in New Mexico had three focus areas. The first was connectivity, acting as a central communication point in a network, De Baets said. The aircraft’s cellular network payload linked teams in Tokyo, New Mexico and Silicon Valley. The two other goals were validating aircraft systems operating in the stratosphere and confirming operations.

Before the flight operations moved to New Mexico, the AeroVironment team brought the Sunglider, then called Hawk30, for multiple initial low altitude flight tests at Armstrong in 2019.

“Those flights verified the basic performance and handling characteristics that showed us we could operate the aircraft safely and effectively,” said Nick Plumb, AeroVironment program manager. “We expanded the aircraft’s flight range for verification and validation of our guidance, navigation and control systems as well as our aerodynamics and aeroelastic stability. It really gave us confidence that we had an airplane that would get to the stratosphere successfully and safely. We learned a lot during our time at NASA Armstrong and it prepared us well to go to high altitude.”

What’s next

The AeroVironment team continues to expand the duration that Sunglider can fly and fine tune the aircraft to prepare for offering commercial services.

“Technology maturity needs to continue and much of that happens through flight test,” Plumb said. “You learn a lot every time you fly.”

Sunglider has benefited from improvements in materials, electronics, and solar-electric propulsion technologies. However, there are still some items that will have to happen before Sunglider will be able to accomplish its intended missions.

For example, AeroVironment is working on a major effort with NASA’s Ames Research Center in Silicon Valley, California, on regulations and standards development for this class of high flying aircraft.

“A lot of concepts from manned aviation, or even typical unmanned aerial vehicles, do not carry over to HAPS in a traditional way, such as safety, risk, reliability, maintenance checks and pilot in command,” De Baets said. “We will have to look at a new way of doing collaborative traffic management and sense-and-avoid, specific standards for electric drive train, and risk of loss per flight hour.”

Concepts for how to pilot a future group of these vehicles that act like a satellite in providing a telecommunications network in remote places is also ongoing. In that situation, a single pilot could fly multiple aircraft together, De Baets explained. Those ideas will be advanced with partners such as the Federal Aviation Administration and regulatory agencies worldwide to grow and harmonize operations.

Experience counts

Sunglider takes advantage of all the lessons AeroVironment’s team has learned from its solar powered aircraft.

“We have a core team that designed and flew Pathfinder and Helios,” De Baets said. “We continued to work on high altitude, long endurance aircraft, and we are able to leverage decades of expertise – from recent grads to experienced professionals. It’s something that really sets AeroVironment apart from others: people have really long careers here. It really changes the dynamic for the better.”

Lessons learned from the past design decisions and aircraft operations allow the team to know why decisions were made and fine tune the approach to challenges.

“It’s hard to point to any area of the Sunglider and not see the influence of AeroVironment’s heritage,” De Baets said. “Even the telecommunication payload mission for the Sunglider stratospheric flight had origins in a mission we flew with the Helios Prototype.”

That’s not to say everything always goes as planned. The Helios Prototype was lost on its last mission on June 26, 2003. A review board concluded events unfolded from an inability to predict, using available analysis methods, the aircraft’s increased sensitivity to atmospheric disturbances such as turbulence, following aircraft configuration changes required for the long-duration flight demonstration. AeroVironment’s team learned from those lessons, which have led to successful aircraft designs such as the Sunglider.

John Del Frate, who was an ERAST program manager and project manager for several of the aircraft, said he has watched the technology evolution since the program ended in 2003.

“I’m personally very excited to see this team continue work started back during the ERAST days,” he said. “The vision we all had then was exactly what Sunglider is all about. Our hope was that new battery, solar cell and composites technologies would allow the concept to break through the barriers faced by Helios.”

De Baets and Plumb say Sunglider’s future is sunny, which is a great forecast for a solar powered vehicle.

“What is fascinating is time and tech have caught up with ability to explore the stratosphere, De Baets said. “Very few vehicles fly in the stratosphere with significant payload capability and we will have the ability to maximize the opportunities offered by the airspace. The goal: affordable persistence. We are helping to develop the foundation for these operations.”