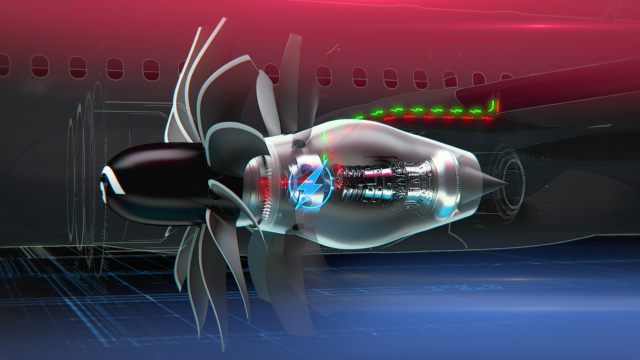

When ice accumulates on the surface of an aircraft during flight, it distorts the smooth flow of air necessary to stay aloft. The result is a reduction in lift, which can lead to stalls and crashes. Knowing about hazardous icing conditions in advance helps pilots, air traffic controllers and airline dispatchers navigate airplanes and passengers away from danger.

However, icing conditions can vary wildly within the same airspace. That’s why scientists at NASA’s Glenn Research Center are advancing the methods, technology and accuracy of sensor systems to provide better detection of potential icing hazards around the nation’s airports.

A ground-based station developed at Glenn includes sophisticated instruments such as a Ka-band cloud radar, which reads particle density distribution; a multi-frequency microwave radiometer that provides vertical temperature and water vapor profiles and a measure of liquid water present aloft; and a ceilometer for refined cloud base measurements.

“Our goal is to improve the tools and data that controllers and dispatchers need to make tactical decisions,” says Aerospace Engineer Andrew Reehorst, who leads Glenn’s icing remote sensor program.

Recently, Reehorst’s team initiated a weather balloon campaign to read and calibrate weather data, and validate the ground-based sensors. Aerospace Engineer Michael King is releasing a series of weather balloons over the winter months from the center’s aircraft hangar ramp.

The weather balloons are fitted with an instrument package to measure pressure, temperature, humidity, and most importantly, supercooled liquid water content. When an airplane comes into contact with supercooled water, it attaches to the surface as ice. As it builds up, airframes are compromised.

“The balloons typically rise to an altitude of 60,000 feet,” says King. “An instrumented vibrating wire is exposed to the supercooled water, which accretes as ice to the wire on contact. From the decrease in the wire’s natural frequency, we can calculate the amount of supercooled liquid water aloft.”

The balloon campaign is part of an on-going effort by the center’s icing researchers to field test and develop products for disseminating icing hazard information to flight crews. An experimental web-based system, currently available only to researchers, provides real-time, raw sensor data to provide a profile of conditions aloft. As the software, computers and sensors are refined, the aircraft community will benefit from access to better information for making critical decisions for overall safety.