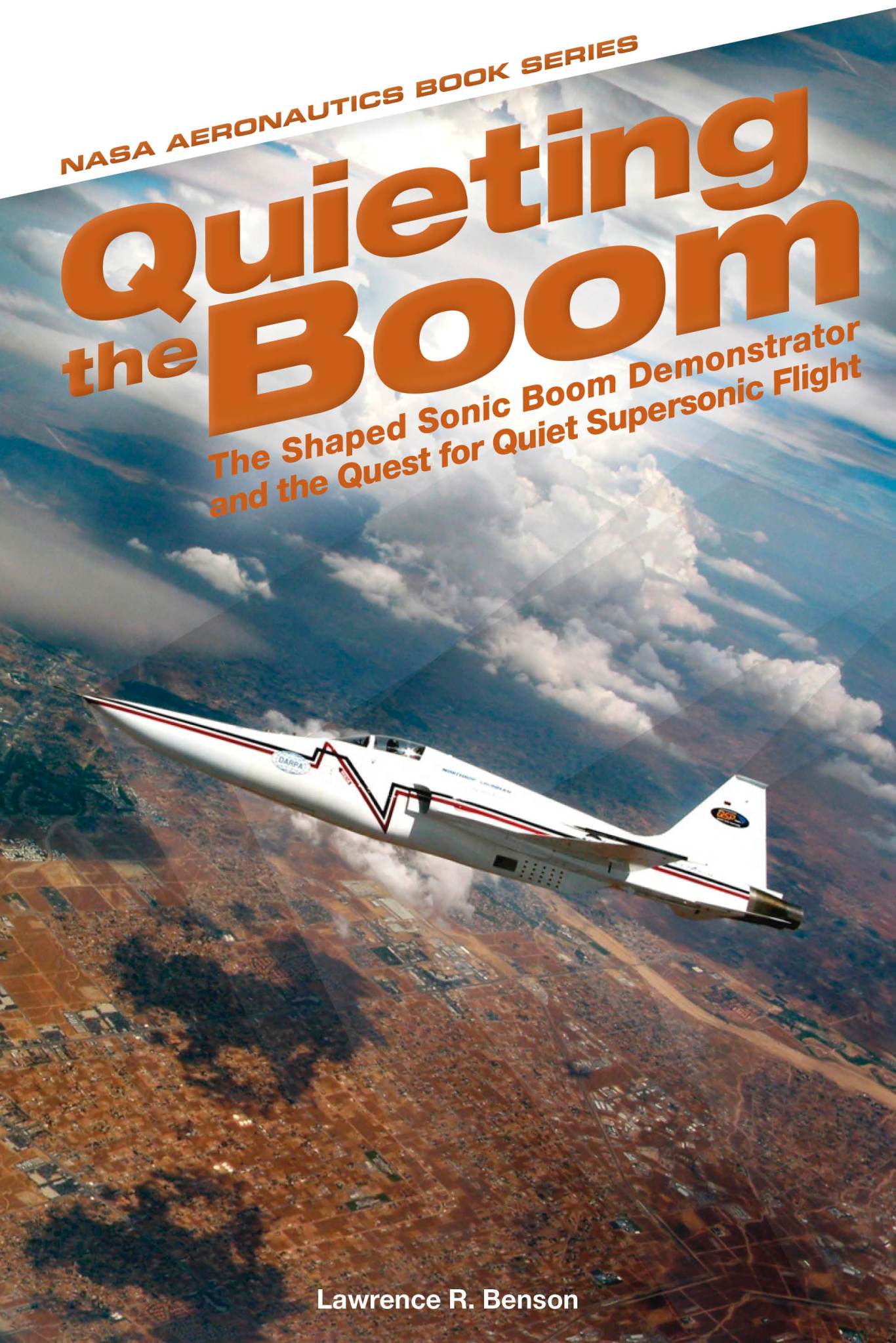

If an airplane flies overhead at supersonic speed and no one below can hear it, did it make a sonic boom?

Answering that twist on the classic falling tree in the forest question gets to the heart of a new book published by NASA that explores the agency’s research into understanding how sonic booms work and how best to make them less of a public nuisance.

“Quieting the Boom: The Shaped Sonic Boom Demonstrator and the Quest for Quiet Supersonic Flight” is available online at no cost as an e-book, while printed versions of the book may be purchased from NASA’s Information Center.

The 388-page book written by Lawrence R. Benson begins with an overview of early supersonic flight that triggered the first sonic booms and sets the stage for telling the story of the Shaped Sonic Boom Demonstrator research aircraft, which is the primary focus of the book.

“I think ‘Quieting the Boom’ shows the value of sustaining basic and applied research to solve difficult scientific and engineering challenges, even if success takes decades to achieve,” Benson said.

During the 1950s and into the 1960s, sonic booms were echoing across the nation as the Air Force deployed more and more of the Mach-1-busting jets that were designed to keep the peace during the Cold War.

But the public voice protesting the noise was just as forceful as the sonic booms themselves.

In fact, as Benson points out in the book, between 1956 and 1968 there were 38,831 claims against the Air Force (14,006 were approved) to cover losses from sonic booms that ranged from broken glass and cracked plaster to assertions of pets dying and livestock going insane.

It was within this difficult environment that NASA and the Federal Aviation Administration led a research effort in support of industry designing and building a commercial supersonic transport, which became known as the SST.

However, even as NASA continued to research sonic booms in support of the SST the public and political pressure became too much. The SST program was cancelled in 1971 and the future for supersonic airliners, business jets and other aircraft became gloomy at best.

Fortunately, the nation’s aeronautical innovators were not deterred. They believed that with additional research a way could be found to quiet the booms enough to satisfy all critics and make commercial supersonic travel possible across the country.

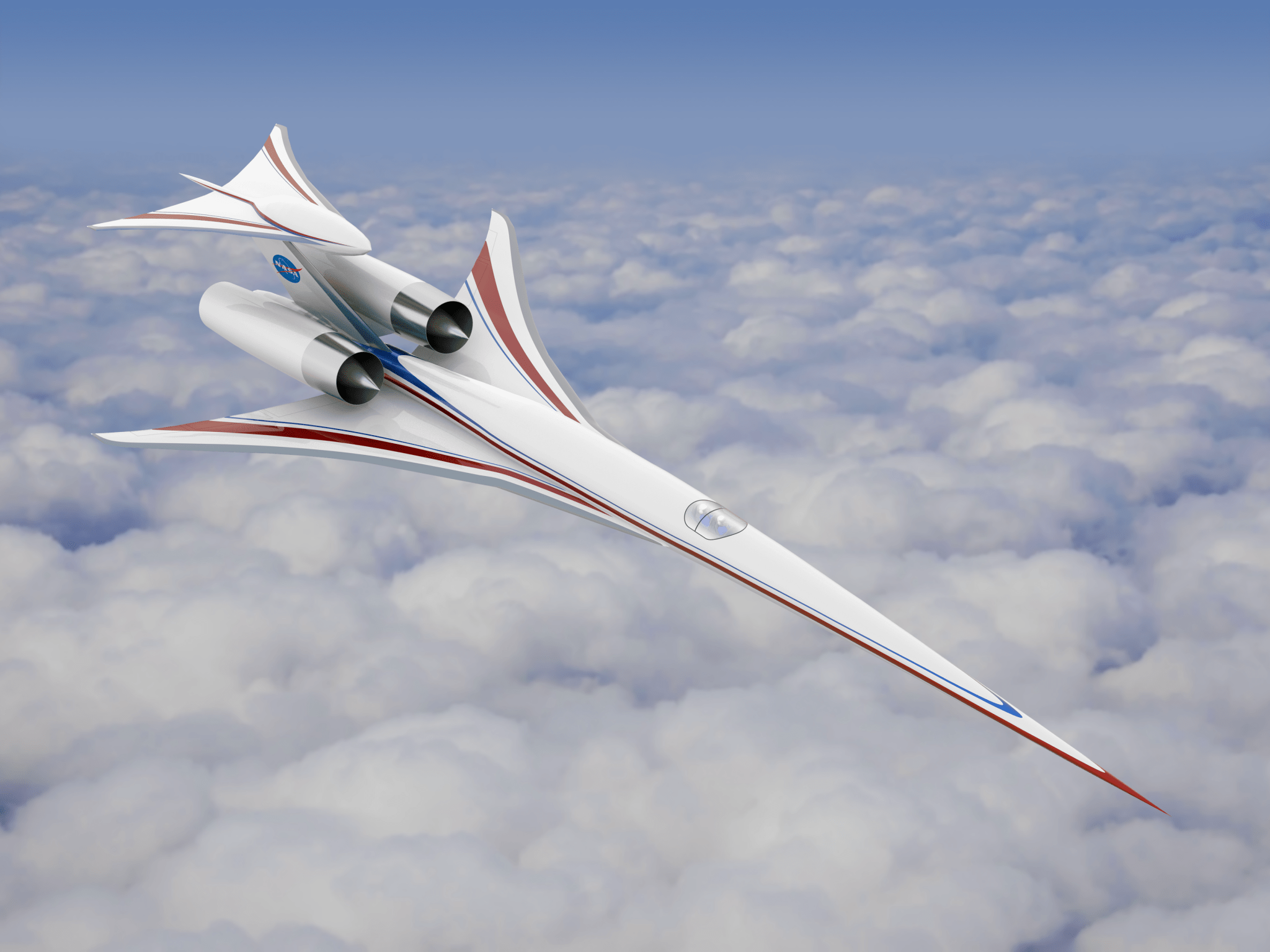

To help them find that solution, NASA partnered with others to conduct an innovative flight research program using what was named the Shaped Sonic Boom Demonstrator (SSBD), a Northrop Grumman F-5E Tiger fighter jet modified with a larger nose.

“This modification, which made the front of the F-5E somewhat resemble a pelican’s beak, was carefully shaped to change the pattern of shock waves it would generate while flying faster than the speed of sound,” Benson said.

The theory behind the nose job was that the increased airplane volume at the front of the SSBD would result in less intense sonic booms heard or felt on the ground below.

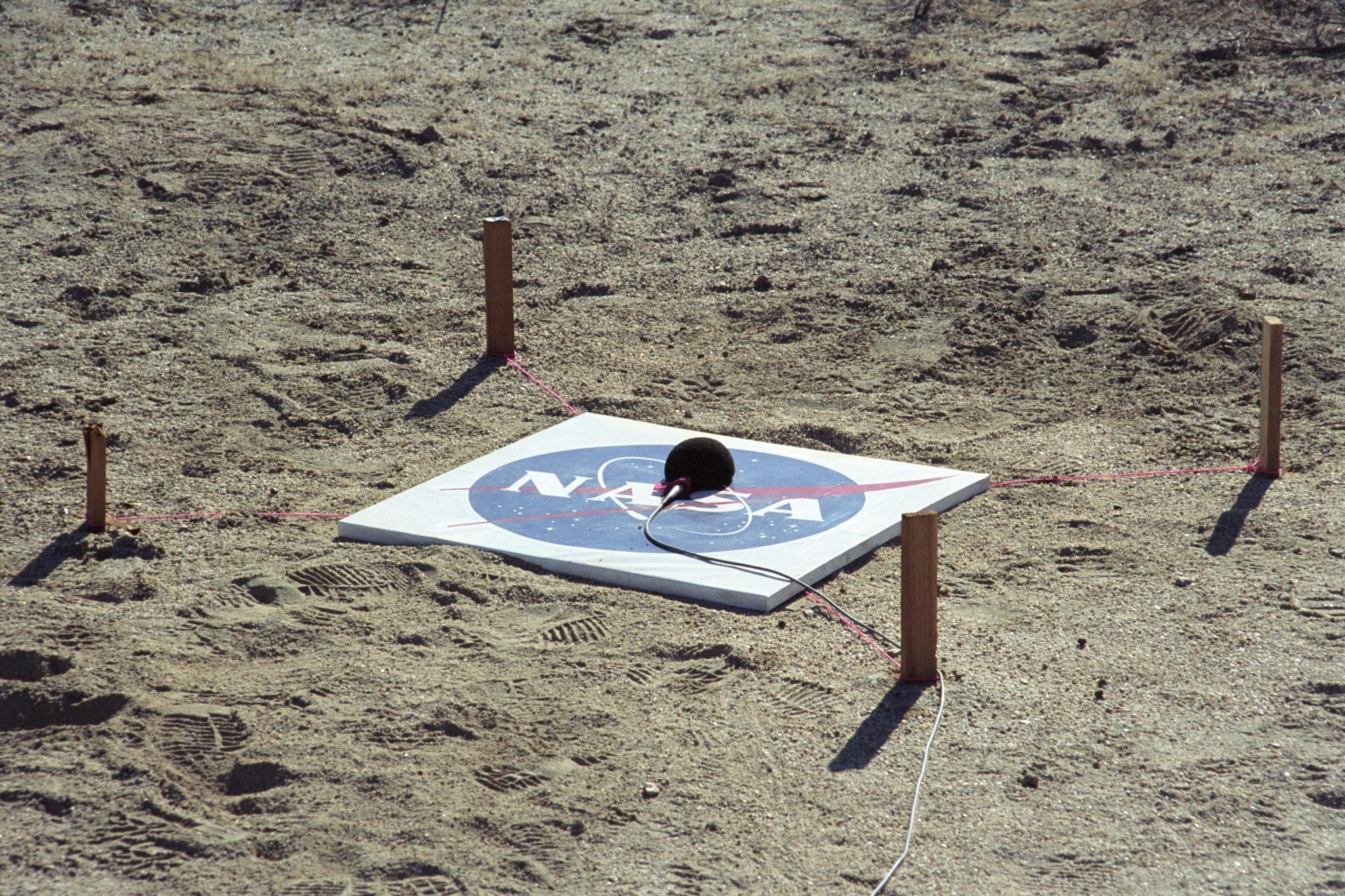

During a series of some 30 tests flown in August 2003 and January 2004, data gathered by airborne and ground sensors of the SSBD in flight proved the theory was – well – sound, and that additional research in the future could enable the long-sought realization of commercial supersonic flight across the United States.

Indeed, that research continues as NASA and its research partners explore fresh ideas and design new tools for making supersonic flight quieter.

Most importantly, in telling what could easily be a complex story involving high speed flight, atmospheric sciences, acoustics and bizarre math, Benson said he attempted to keep the technical jargon to a minimum.

“This book is intended to be a general history of sonic boom research, emphasizing the people and organizations that have contributed, and not a technical study of the science and engineering involved,” Benson said.

The American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics has recognized the book with its prestigious History Manuscript Award for 2014.

Publication of “Quieting the Boom” was sponsored and funded by the communications and education department of NASA’s Aeronautics Research Mission Directorate.