Not long ago, Fay Collier’s eldest daughter forwarded him an email containing a nugget of folk wisdom.

“Arguing with an engineer is like wrestling in the mud with a pig,” it read. “After a couple of hours, you realize the pig likes it.”

It was meant as a playful dig, but Collier saw the truth behind the joke.

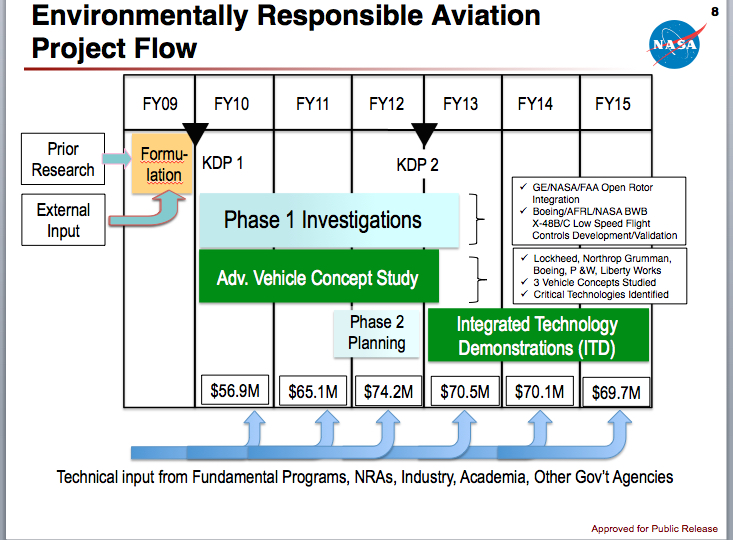

“A lot of us are like this, aren’t we, as engineers?” said Collier, who led NASA’s Environmentally Responsible Aviation (ERA) project, a six-year, $420-million effort to find ways to reduce fuel consumption, pollution and noise created by commercial aircraft. The project was completed in 2015.

“We get in a room with a few of our colleagues, we argue back and forth,” said Collier, who is based at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia. “I’ve got to tell you, I really do like that.”

While this kind of friendly mental jousting can make working for NASA fun and rewarding, he said, he also believes that ERA wouldn’t have achieved such dramatic results if his team had argued more and listened less.

“In the end, one of the keys to our success was that everybody, I thought, had the chance to bring their strengths to the table — and exercise their strengths,” Collier said.

“That’s really key.”

The value of teamwork was one of the messages from Collier’s March 18 professional development talk presented by the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA) and the NASA Langley Aeronautics Research Directorate. In his talk, “The Environmentally Responsible Aviation Project: Start to Finish,” Collier described how he led the project and offered insights into what worked and what didn’t.

He said expansive projects like ERA aren’t likely to succeed if dominated by one person, or even by a handful of leaders.

“In an effort like this, across four centers, 150 people and a large industry component, you’ve got to figure out how to let go, release control and let some of this happen,” he said.

“You have to put yourself in a listening mode and pay attention to the smart people around you.”

ERA’s big numbers

That collaborative spirit led to big achievements.

If the work of Collier’s team is implemented, the nation’s airlines could save upwards of $250 billion between 2025 and 2050. Techniques and technologies developed and refined by NASA researchers and their ERA partners have the potential to cut airline fuel use in half, pollution by 75 percent and noise to nearly one-eighth of what’s produced today.

Noise from aircraft operations remains the top obstacle to improving the nation’s air transportation system, Collier said. NASA’s ultimate goal is confining noise to within an airport’s boundaries. That’s ambitious, but ERA’s work yielded big results. It illuminated a path to an envisioned 80-percent cut in noise from takeoffs and landings.

Relentlessly pursuing that goal over time helped make progress possible.

“So, that’s another lesson,” Collier said. “Set a goal, stay focused on it and keep working it.”

Eight elements

ERA researchers completed eight technology demonstration projects, each with the goal of helping aviation become more environmentally friendly:

- Tiny air nozzles embedded in an airplane’s vertical tail fin that create air flow, allowing future aircraft to be designed with smaller, lighter tails

- A new process for joining large sections of lightweight composite materials allowing new, durable, more efficient aircraft designs

- A new morphing wing technology that would let an aircraft to adjust its shape on the fly

- More efficient turbine engine compressors

- An advanced fan design allowing for more efficient, less noisy, geared turbofan jet engines

- Improved design for a jet engine combustor capable of cutting pollution by as much as 80 percent

- New tools for designing low-noise wing flaps and landing gear. Information from a set of wind-tunnel tests was combined with flight test data to create computer-based simulations that will aid future designs.

- Studies on a hybrid wing body concept in which the aircraft’s wings join its fuselage seamlessly, creating smoother contours

New ideas about airplane designs are particularly important, Collier said. “It’s the power of integration, right? So, you’re not hanging the engines off a wing anymore, but you’re trying to figure out how to blend fuselage, the engines and the wings all together to achieve very significant results.”

Reading the reaction

Collier’s talk gave the audience a taste of what it’s like to manage a large-scale, collaborative NASA project.

“I found it very helpful,” said Kevin Disotell, a postdoctoral fellow working on a new wind tunnel experiment for NASA Langley’s Flow Physics & Control Branch.

“He had good insight into the logistics of project management,” Disotell said. “I got a lot of good advice about the nature of people and how understanding that leads to effective management.”

For example, Collier told the crowd that the ERA team arranged work schedules to avoid burnout and set deadlines with enough cushion to lessen employee stress.

“Understanding human nature in a project full of people like that is so important,” Disotell said.

Also, Disotell was interested in ERA’s success at forging industry partnerships. Boeing, FlexSys Inc., Aviation Partners of Seattle, General Electric and Pratt & Whitney all participated in the project.

“This is the kind of thing I came here to work on,” Disotell said.

Sam McDonald

NASA Langley Research Center