Orion Program Manager Mark Kirasich discusses the challenges and opportunities of managing America’s next-generation spacecraft.

Mark Kirasich: We say, boy, in this new area, I’m willing to try this innovative approach, which hadn’t been done before and therefore has risk, and we’ve done that on Orion in a couple of cases.

The only way you can have zero risk is to never fly. So a key part of my job is to balance the risk.

If you look back too much, it stifles innovation. The young guys and women who just got out of school and have the latest and greatest knowledge and energy can bring a lot to the problem.

Deana Nunley (Host): You’re listening to Small Steps, Giant Leaps, a NASA APPEL Knowledge Services podcast, featuring interviews and stories, tapping into project experiences in order to unravel lessons learned, identify best practices, and discover novel ideas. I’m Deana Nunley.

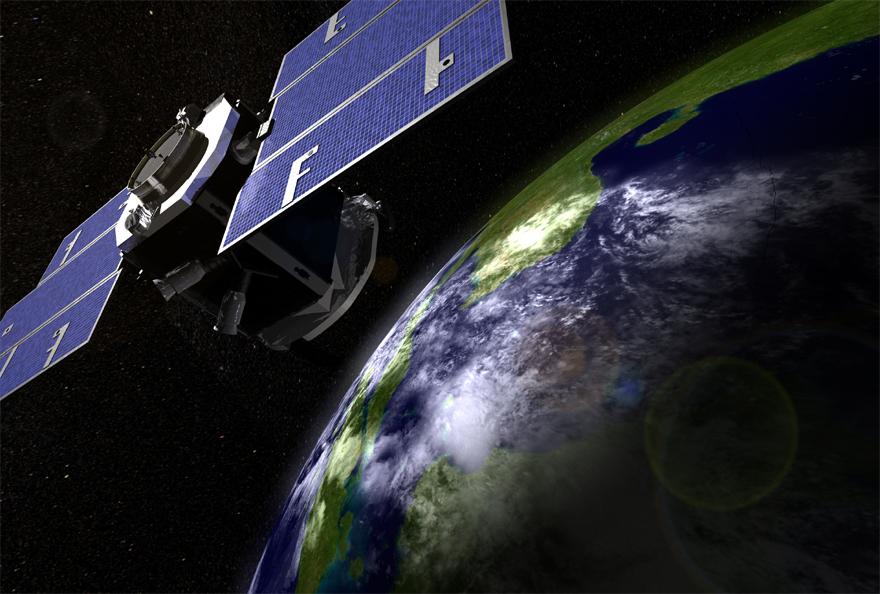

Named after one of the largest constellations in the night sky and drawing from more than 50 years of spaceflight, research and development, Orion is America’s exploration spacecraft, designed to carry astronauts to deep space destinations, including the moon and then on to Mars. During a recent Virtual Project Management Challenge, Orion Program Manager Mark Kirasich discussed how Orion supports NASA’s deep space exploration agenda, and how the leadership team manages a complex project involving multiple components, partners and facilities.

Today, we’re featuring some of the stories Mark shared during the July 2018 Virtual Project Management Challenge.

Kirasich: I’m glad we have the opportunity to talk, so I can share stories about something I’m very excited about, and that is human space exploration. We’re part of a larger system and what we’re really about is sending people, human beings farther into space than we’ve ever gone before and exploring new places. Orion is a human capsule piece of that, but you can’t do that with just Orion.

Our nearest set of friends and colleagues are a group of folks called the Exploration Systems Enterprise. That consists of the rocket, the Space Launch System, which is the biggest, most powerful rocket that people on Earth have ever built, and also the Exploration Ground Systems Project, the people at the Kennedy Space Center, who will do the final assembly, the integration of Orion to the rocket, the fueling, and will ultimately conduct the launch countdown that is going to lift us into space.

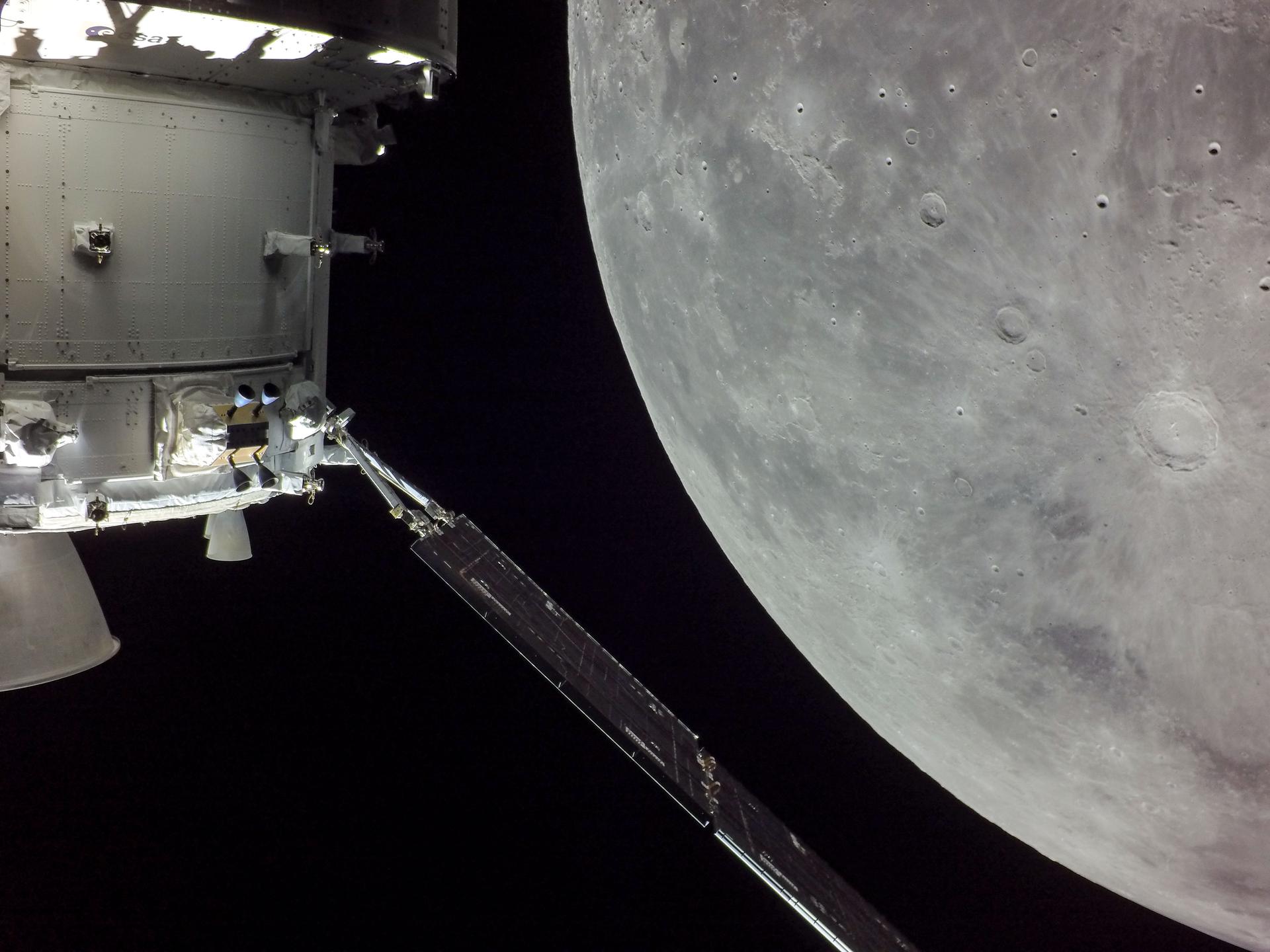

Then next, we have to have a destination. We have to plan where are we going to go. How are we going to get to Mars, for example? Just recently, over the past year and a half, that part of our exploration plan in the agency has come into better focus. The way we’re going to do it, we’re going to build something called the Deep Space Gateway, which is going to be a spaceport, a small spaceport, a couple of modules that we are going to put into orbit around the moon.

It will be in a stable orbit around the moon. In many ways, it will be similar to the space station in low-Earth orbit. It will be smaller, but it will be out at the moon. The reason we put it there is because it’s farther away from the Earth, where we can learn to live and work, where you don’t have the close dependency, the ability to get home in an hour.

This orbit around the moon is really a great jumping off point, depending on where you want to go next. We can send landers to the surface of the moon. We can bring them back up. We can send spacecraft and people on destinations further away from Earth from this Deep Space Gateway.

Orion started as Apollo, the last time we sent humans beyond Earth orbit, was winding down. Many people here at the Johnson Space Center, many people at NASA, here in the country, part of their dreams are to send humans into space, into space exploration. So when Apollo ended, we’ve always had people who have dreamed, who have architected, who have planned out what a future exploration spacecraft would be like.

We actually, as Orion got formalized in 2006 by the second President Bush, as part of his vision for space exploration. So we started in 2006 and we’ve had to adapt. We’ve had to change over time. In fact, in 2006, for people that weren’t around in NASA then, it was after the shuttle Columbia accident, and the agency had set an endpoint for the Space Shuttle Program. It was going to be in 2010.

So when we started, our immediate goal, since we had the space station up there and the shuttle was coming then, our immediate goal was we were going to be a space station resupply and a way to get crew back and forth from the space station. So our initial mission was to go to the space station, and our goal was close the gap. Fly Orion as early as possible after shuttle ending. So that was our start.

Now then it became apparent, because we wanted to do these really incredible things in deep space, it became apparent that we had to make choices. Design Orion for here. Design it for deep space.

In Orion, we built in flexibility, but eventually what we did, the agency came up with a new strategy that said, “We’re going to have commercial spacecraft built for low-Earth orbit. We’re going to optimize Orion for deep space missions.”

On deep space mission, we’ve had a variety of missions. We have been designed to take landers to the orbit of the moon, drop them off. Again, as I mentioned, now we’re an integral part of the Deep Space Gateway. We will help build the gateway.

Host: In addition to the technical challenges of carrying humans through the harshest environments and safely returning them home, the Orion Program has also faced changes on the political front.

Kirasich: We’ve had a lot of challenges, technical, and boy, the technical list is so long. By the way, if the list is long, the amount that we’ve successfully resolved is almost 99 percent of the top. As soon as you get one, another one pops up.

But as I think back, perhaps one of the program’s biggest challenges wasn’t technical in nature. It was one of these external changes. I talked about how you have to adapt before, but some of the folks who will be listening to this course might remember that it came with a political transition. We had a new president. New presidents promise change, and we did. Barack Obama came in and he wanted to change NASA, and one of his changes was he proposed that Orion be cancelled, believe it or not. 2010, it was February 1. We had no advance notice.

I was sitting in this office with my boss. They said, “Hey, you’re going to want to watch the administrator’s news conference tomorrow.” So we did, and we were a little bit surprised when we heard one of the goals for the next year was we’re going to cancel Orion.

So as you might imagine, that was a challenge for a number of reasons. Number one, many of us, many of the people believed in Orion. We believed in space exploration. A lot of people had invested a lot, a lot of people. So you have everything from goals to some people’s livelihoods depending on Orion.

So that was one of the biggest challenges we ever had. By the way, also I had never been to a course, a program managers’ course, a virtual program manager challenge where they said, “This is the checklist that you go through when you’re proposed to be cancelled.” So we really had to do a lot of open field running in that event, but some of the basic principles still apply. Set visions and communicate. Really, it was those two things, especially initially, especially in the early days, that kept the team together.

For example, the very next day at eight o’clock we had a program all-hands, because the day before the administrator said we’re going to be cancelled, we had to tell the 5,000 people on Orion, across the country, “Hey, this is what was said. This is what we know.” We didn’t know a lot, as you might imagine. They didn’t tell us, but we got everybody together. Mike Coats was the center director. On that day, he came down. He participated with us. He helped us.

The other thing in those kinds of things, there’s a fog. You’ve heard the phrase, “a fog of war.” I can talk about it in hindsight with precision today. On that day it wasn’t this clear, but you notice I used the words, “proposed to be cancelled.” We were proposed to be cancelled, but really, since we were a congressionally authorized and appropriated program, the Executive Council couldn’t actually cancel us.

So that was kind of a subtlety we didn’t know about at the time, but as we worked through it, we talked to the team. Yes, we were proposed to be cancelled. “Well, what does that mean?” the team would ask you. Well, what it means is for the time being, we want you guys to keep going. We’ve got a really important job to do.

So we spent a lot of time traveling around, defining our vision, “Our vision is this. We want to keep going.” By the way, one of our big flight tests, that was February 1, 2010, our first test of our abort system at White Sands Missile Range actually occurred in May, three months afterwards. So one of the things we said was, “Hey, we’re not going to stop. We’re going to go do that test.”

So what we did, again, our vision was let’s keep the program going. We still had our annual budget. Our annual budget back then was about a billion dollars a year. We had a billion dollars. We’re just not going to waste it. Let’s keep doing good work, while we worked with our bosses in Headquarters, “Hey, what does it mean to be proposed to be cancelled?” And we had to figure that out.

Eventually, as you – I can tell you the story now. Congress believed in the human space program, especially human space exploration, especially Orion. It was actually Congress who in the fall of that year reaffirmed their support and said, “No, we’re not going to cancel Orion,” and Orion was actually written in by name, into the public law. Actually to this day, every year we receive our own appropriations.

So that was a pretty interesting time because, like I said, there’s no playbook. We had to react. But the principles, the principles of setting goals, talking to the team, dealing with issues deciding, the principles used every day were really applicable then, too. It wasn’t clear that we were doing it, but we somehow managed to get through it.

Host: Mark offered insight into the progress being made.

Kirasich: The fact that you’re here in 2018, it’s a really exciting time. Today in 2018, we have more hardware and software in manufacturing plants, in our assembly plant in Florida, in test labs around the world than we’ve ever had before. We often talk about it as we have five major campaigns, production and testing campaigns ongoing simultaneously.

First off, we have the three vehicles that are going to go into space, that are going to travel to the moon. The Exploration Mission-1, the Exploration Mission-2, and the Exploration Mission-3 vehicles are in various states of production. Exploration Mission-1, the crew module and the service module are almost done at the Kennedy Space Center and in a factory in Bremen, Germany, as we sit here today.

For EM-2, the primary structures for the crew module and the ESA service module are complete, and are just being shipped to the factory in Bremen and the factory at Kennedy Space Center.

Then for EM-3, we call it long-lead procurement. The materials and the components that become the primary structure, for example, they start out as raw plates of aluminum. So we buy aluminum from our country’s aluminum manufacturers and we send them to aerospace precision machine shops around the country. So that work for EM-3 is underway.

In addition to those three exploration flights, if you will, we also have a really important test flight. It’s called Ascent Abort-2. It’s a test flight that we’re going to do to test the launch abort system. It’s an unmanned test flight that we’re going to do nine or ten months from now, in April of 2019 from the Kennedy Space Center, where we have a rocket, a relatively low-cost rocket called an abort test booster that’s going to simulate the Space Launch System, and put Orion on a trajectory just like the SLS will, but at a certain point in the trajectory, the most demanding part of the trajectory, where we’re still in the atmosphere, but we’re flying really fast, so the aerodynamic forces on the crew module are really high, we’re going to abort at that instant. We’re going to intentionally abort, to make sure the system operates in that environment. So that’s our fourth major campaign.

Then our fifth major campaign has to do with vehicle qualification of all the major systems, our propellant system, our avionics system, our structure, our primary structure. We have full size, you can imagine really big test articles, very high fidelity test articles of each one of those systems at different locations. We’re doing structural qualification at a Lockheed facility in Denver, Colorado. We’re doing a propulsion system qualification using what we call PQM, a propulsion qualification module at the White Sands Test Facility. It’s out in the middle of the desert, away from the population, because it can be hazardous testing. We have an avionics lab, where we bring our hardware and our software together, put them together and validate the software with the hardware.

So we have a lot going on, five major vehicle campaigns all going on in parallel day in and day out here in Orion. I have an opportunity to interact with many of the other project managers across the agency.

First of all, there are a lot more common themes than one might realize. One of the things that almost all NASA project managers that I’ve talked to have talked about is resources, financial resources and schedule. You never really have as much as you’d like. Really, that’s almost by design. You want to invest. You want to invest whatever money is available, whatever schedule is available into making the spacecraft as good as possible, giving it as much performance as possible.

So the interesting thing that all of us might tell you is, boy, it’s hard. It’s hard to manage the budget, manage the schedule. You never have as many resources as you’d like. So that’s a common trait.

You talk about the life cycle. You write requirements. You talk about what is it I want to do, and you codify that in requirements. You manufacture. You build. You go through testing. You get to flight and then you learn from it. That’s very similar.

Maybe the differences, if it’s bigger, almost by definition, it takes more money. It takes more time. Maybe one of the differences is when it takes more time, over time, the time it takes from when you start to when you get to flight and before you have your metal cut, there’s opportunities for change. We find that especially happens when there’s big political changes, when we get new presidents. New presidents come in and they have new ideas. They don’t want to land on the moon. They want to build a spaceport around the moon.

So one of our differences is it takes us longer. We live through cycles of change and we adapt. So that’s probably one of the biggest differences in the time it takes. We find that we have to change often. We have to adapt to different ideas and different directions.

Any time you bring two things together, be it two pieces of hardware or two different cultures, you have to understand the differences and you have to be careful of how you bring them together. Nowhere is that more apparent than in our international partnership.

First off, I’ll start out by saying that the European Space Agency is an incredible space agency, who has accomplished many things in space that in fact we haven’t. They’ve gone to destinations. They created the ATV, the autonomous transfer vehicle, which was an unmanned resupply vehicle for the space station, but, for example, was the first time demonstrated a completely digital automated rendezvous and docking capability. So they’ve got incredible talent. They’ve had amazing successes, as have we. What you find when you bring the two organizations together is the cultural differences.

That’s really when you talk about interfaces and the human interfaces. That’s what it is. It’s about, “I grew up at NASA and we think in order to do it right you do one, two and three.” Then you meet your ESA colleague, who has just as much experience, is just as hard working, is just as talented, but guess what, their lessons learned are A, B and C.

So what you do is actually you have an opportunity. You have an opportunity to identify the strengths and the best practices of each organization to make an overall stronger organization. It takes time and effort to work through that, “I think 2 is better than B.” You have to work through those differences, and that’s the complexity of, for example, an international interface.

But it’s not just international. It’s not just the Europeans. Orion is a multi-center project and people here at Johnson, we have our own culture and we work with people from across agencies, from Kennedy, from Glenn, from Marshall, and with those interfaces you establish a good relationship and you work through the different things.

Host: Mark discussed several skills project managers need, such as the ability to guide the decision making process, getting the right people on the job, and not letting them come to a solution too quickly. He mentioned a couple of pieces of advice he wishes he could have had when he started as a program manager.

Kirasich: First of all, you’re not as smart as you think you are. Like I told you, being in this job now for three years, the thing I learn more and more every day is how much I don’t know. So really, I said it one way, but it’s really about listen to the people who are smarter than you are, closer to a problem than you.

There’s another saying I’ve learned in Orion. Truth is at the factory floor. Factory is one term. It’s wherever the point of the work is. For example, if I’m building the capsule, the truth is if I’m the guy that’s actually turning the wrench, that’s putting the bolt in, here in the program I’m seeing a viewgraph that’s gone through three different layers of reviews and management that’s telling me, “He was turning the bolt and he broke it.” So the truth is the person that was turning the wrench. So you listen a lot and you make sure you understand the problem and you learn, and you learn you’re not as smart as time goes on. To be honest, I’ve learned that at every job. I learned that lesson as a flight director. It took me a while. I’m not the smartest flight controller. I’ve got to listen to flight controllers.

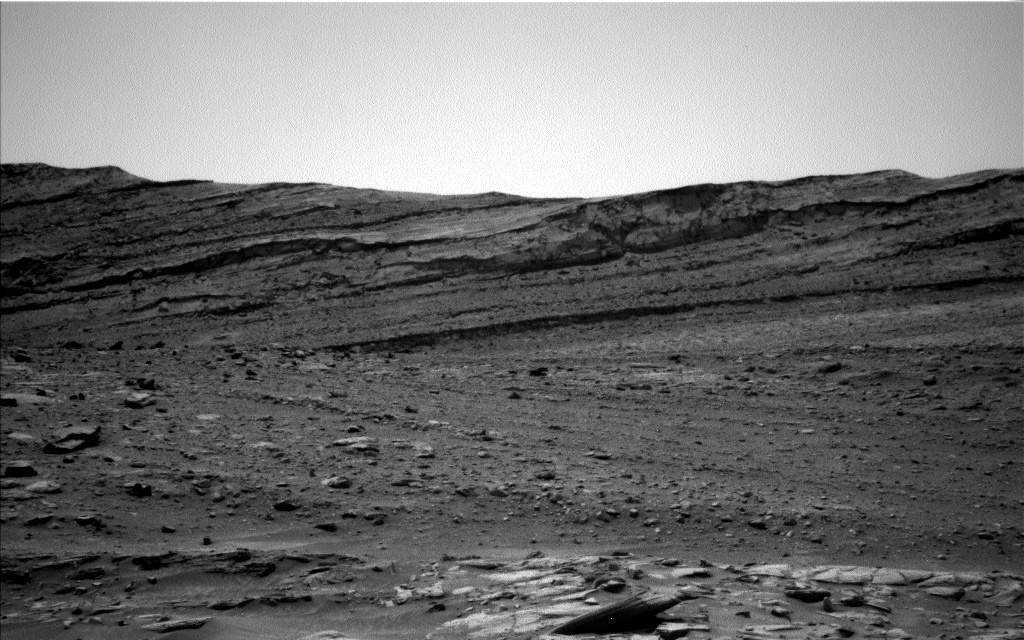

Human spaceflight, the prospect of propelling people from here, where we walk and run relatively slowly, but accelerating them to thousands of miles per hour, and then having to decelerate them. Then in the middle, they’re exposed to a really harsh environment with no air, with high radiation, where you’re in the sun directly and you get really hot, and then when you’re shaded from the sun you get really cold. By its inherent nature, it’s really dangerous, and come with danger there’s risk, and the only way you can have zero risk is to never fly.

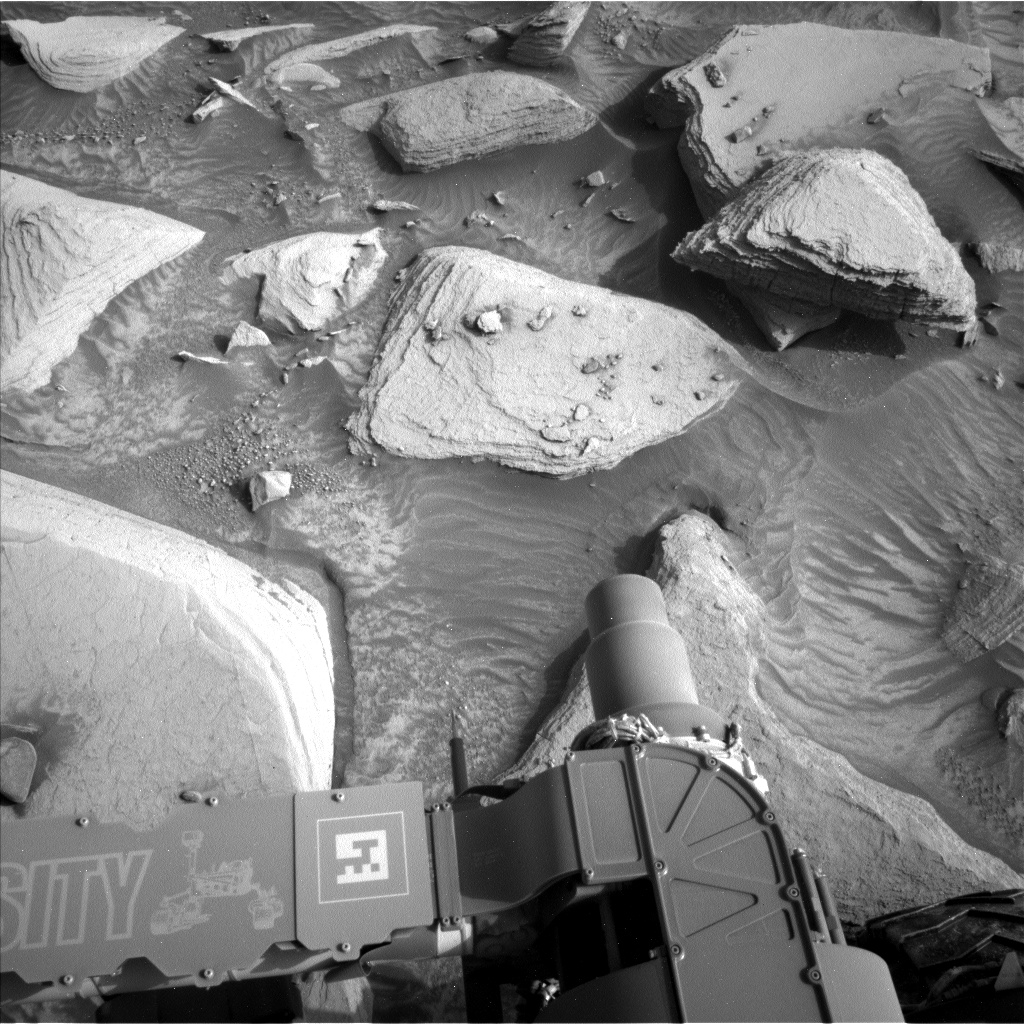

So a key part of my job is to balance the risk. When you have a risk, and we have many of them, what you do, first of all, you put together a technical team who are experts in that particular area. What comes to mind is, for example, our heat shield. When you come back from a beyond Earth orbit mission, you come back into the Earth’s atmosphere much faster, for example, than when you’re coming back from low-Earth orbit. When the heat shield hits the atmosphere at these tremendous speeds, it gets really hot, over 4,000 degrees, and it generates plasma fields.

So the heat shield actually is one of most technically complex systems on the whole vehicle. In fact, there’s a really big technical risk. So what we do is we get the agency’s best and brightest engineers to work for years on it. They put together subscale models, and we test these models and arcjets, and we get really smart. We say, “Boy, if we make the heat shield a little bit thicker, we can reduce risk. If we change this constituent material, if we increase the percentage of this,” and we do that for a period of time, until we say, “Boy, we’ve looked at the risk and we’ve looked at the effort it would take to go further, either in adding mass.” The cost of reducing risk can be in a lot of different currencies. It can be in real dollars. It can be in mass of the vehicle. It can be in time it takes.

So what we do is we push on the technical problem long enough, until we make a judgment together, the technical team and myself, “We’ve taken this to a point where we’ve pushed the risk down and we’ve made it this small, and to go any further would take, boy, a lot of additional weight or three more years.” That’s how we make those judgments, risk balancing.

You also try to do a spacecraft that has to deal with this many different sorts of hazards, radiation, heat, just the process of taking carbon dioxide out of the air and being reliable. You want to make sure – we try to risk balance across the spacecraft.

What I could do, I could make the heat shield the safest possible heat shield that humanity has ever known, but I might spend so much of my resources, my money, my mass, my time, that maybe my solar arrays aren’t strong enough or have a weakness, a radiation weakness. So the other thing we try to do is we try to risk balance. We look across the vehicle and say, “Are we investing our people’s time in the things that have the biggest bang, if you will, for the amount of resources we have available?”

Most of the things that I do today to keep our team in sync, I learned early in my career, part of my first leadership course, Management 101, and it’s really the same sorts of principles that you learn when you go to your first management course, listen very closely to, and then continue to practice as you go through your career. But I try to do things that we learn about leadership very early.

Number one, a leader needs to set goals. What are the organizational goals? In a large program, we have a fancy name for that. We call it a vision. What’s the organization’s vision? So I set a vision.

The next important thing – by the way, part of that vision is getting the organization to buy in, especially in large organizations. I can think we ought to go left or I can think, “Well, we’ve got to go to the moon,” and somebody else might think, “We need to go to Mars.” With things like vision, you have things called buy-in. So we spend time as a senior management team. We get our senior management team.

For example, prior to this year, getting to this five-campaign, we were transitioning from being a single or a dual campaign team into a five-campaign team. Our strategic council, our management team focused on, “We’re going to have to change. Our vision for the next year is going to have to be to do five things in parallel.” We got the buy-in, and then we talked about how do we do that. So that’s one thing, set the team’s goal.

The next thing I would say is communicate. Communicate a lot, especially with a team of this size. You have to strategically communicate and then tactically you need to manage the execution. You need to deal with the issues that arise daily. So we have a variety of different ways we communicate with people from across the team.

It starts with a daily telecon every morning. Houston is in the middle of the country, so we kind of pick a time. It’s eight o’clock Houston time. It’s a little bit later on the East Coast. It’s a little bit earlier on the West Coast. But everybody on the Orion team – excuse me, not everybody – a representative from every major organization on the Orion team tags up once a day at eight o’clock and it goes really quick. A lot of times we’re done in 15 minutes.

But what we do is we say, “What’s big on today’s plan? What’s in the Arc Jet at Ames? What’s in the factory in Florida? What broke in Denver?” We try to do that in 15 minutes, so everybody knows what’s going on.

Then we get together face-to-face. We do it weekly in a scheduled business rhythm, where we go through each one of the five campaigns in detail, “What did we do last week? What are we going to do next week?” Then we have quarterly meetings, where we get the management team together, “What did we do last quarter? What are our problems? What are our goals for next quarter?”

As the program manager, I’m really almost the least knowledgeable person in the entire program on any specific problem of the day. At Orion, we have incredibly talented – we have the agency’s best engineers and scientists in almost every system on the spacecraft. So I depend on them and that’s kind of obvious. I don’t know – I couldn’t tell a prop engineer or a structural engineer how to solve a stress problem or a fracture problem. I really need their help.

The way we kind of codify that in Orion is generally we try to push decisions down to the lowest possible level. We have a weekly board. It’s called MPCB, the MPCB Orion Program Control Board. The best weeks, in my view, are the weeks that we don’t have one, because what that means is it means all of the lower level boards are making the decisions, and everything is within their realm of influence and they’re able to solve the problem.

So really, what bubbles up are the things that the lower boards can’t resolve. Then what happens when it gets to the board? Well, again, it’s not just me, but the board consists of the representatives of all of these organizations that manage all the best and brightest people. So really, the program manager is never alone. The program manager has the benefit of all this expertise.

NASA has an incredible history and a lot of amazing successes, and we have tried to learn a lot from them. We have people who did it in Apollo, did it in shuttle, did it on space station. Hey, what did you do in this time frame?

Also, NASA tends to codify, write down and put for the record lessons learned in a number of different ways. We have knowledge databases. But the most formal thing is we have NASA design standards. We have the NASA spec for how to do welding. We have the NASA spec for how to do pressure vessel testing, a NASA spec for how to design good structures. So we codify our lessons learned and specifications and requirements.

I will tell you that is the one thing, especially now, that NASA has a 50-year storied history, 60 years almost. We’re going to be 60 this fall. After a while, these books of lessons learned get so big, “You’ve got to do this, this, this and this before you wash your hands to do the welding.” What it tends to do is you have to be careful, because if you look back too much, it stifles innovation. The young guys and women who just got out of school and have the latest and greatest knowledge and energy can bring a lot to the problem.

So that’s another thing program managers do. We balance how many of our lessons learned we use and put into practice, and we say, “Boy, in this new area, I’m willing to try this innovative approach,” which hadn’t been done before and therefore has risk. We’ve done that on Orion in a couple of cases. A couple have worked out really well for us. One of them didn’t and we had to have a backup plan. So you balance things.

You look. You try not to repeat the mistakes of the past, but you also don’t want to be so bound by the hard lessons learned that you don’t think and you don’t innovate as you move forward. Again, the definition, keep the project moving forward despite setbacks. There are always going to be failures. There’s always going to be problems. That’s part of being a program manager, “Okay. That broke.”

I’ll tell you an interesting story. When we were building the Exploration Flight Test-1, it was our first spacecraft that we put into orbit. When we were building the crew module structure, we do a test called a proof pressure test. The structure is built. You pressurize it, and then you pressurize it to 50 percent higher than it’s going to operate at, to make sure it’s strong enough.

When we did ours for EFT-1, I remember the day very well. During that day, I was going to fly from Houston to Huntsville, for one of our quarterly meetings that I talked to you earlier about we do. I had my iPhone. It might have been a BlackBerry that day. You know how when you’re getting ready to take off, they close the doors and say, “Everybody turn off their devices.” So I look at my device. I’m about to hit the off button, and there was a message that said, “We were doing the proof pressure test and we heard a loud bang.” And that was it. And then they made me turn off my device.

What we did was we cracked the structure. We didn’t build the structure strong enough. So it was a huge – relatively, at that time, it was a huge setback. It took us three months. You can imagine. If you crack your pressure vessel, that’s not good. We had to repair it. But that was just one and we have them daily. They’re not all that big, but you have setbacks. You have to move on.

That is an incredible day when the whole team comes together and participates in a flight test. We’ve done it twice so far on Orion. It culminates on launch day, when the years of work to build one of these comes together and we put on a rocket and we go.

Host: Thanks to Mark for sharing his knowledge and stories about Orion program experiences. The entire Virtual Project Management Challenge session is available to view at nasa.gov/vpmc. For Mark’s bio and more information about Orion, as well as a transcript of this podcast episode, please visit appel.nasa.gov/podcast. If you have suggestions for future topics, please let us know on Twitter at NASA_APPEL and use the hashtag SmallStepsGiantLeaps. Thanks for listening.