From Earth orbit to the Moon and Mars, explore the world of human spaceflight with NASA each week on the official podcast of the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. Listen to in-depth conversations with the astronauts, scientists and engineers who make it possible.

On Episode 233, NASA communicators describe the various ways that the agency connects with mass audiences. This panel was recorded on January 21, 2022.

Transcript

Gary Jordan (Host): Houston, we have a podcast! Welcome to the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, Episode 233, “How NASA Communicates Space.” I’m Gary Jordan, and I’ll be introducing this panel today. On this podcast we bring in the experts, scientists, engineers, and astronauts, all to let you know what’s going on in the world of human spaceflight and more. You’re probably listening to this podcast because you’re interested in space. To quench that interest, you in particular decided that podcasts was the way that you were going to learn this stuff that you’re interested in. Maybe you also watch our live programming or visit our websites or download posters. In any case, how NASA communicates with different audiences is part of a strategic communications plan and approach, all backed by an agency charter that tells us the communicators to reach out to a massive audience. Recently, I had the privilege to speak on a panel, hosted by Space Center Houston, with some talented communicators at NASA about why and how we do what we do. I very much enjoyed the discussion and I think it does a good job of laying out the many unique ways that we reach out and connect with audiences. I asked the museum if we could perhaps rebroadcast the discussion on this podcast and they were kind enough to let us share it. The panelists are introduced by Space Center Houston’s CEO, William Harris, who moderated the discussion. So let’s get right into it: how NASA communicates space. Enjoy.

[Music]

William Harris: For six decades, NASA has been doing amazing things and the scope of its scores of research projects keep expanding. From better understanding Earth and its systems to exploring our solar system, the universe and beyond. How does NASA share the remarkable programs and discoveries? This is a very challenging goal. This Thought Leader program will focus on how NASA communicates some of its many exciting programs. The tireless communicators at NASA are figuring out how to tell these stories, helping us marvel at the engineering feats of achievement and remarkable scientific learning happening every day. I’m delighted to welcome our panelists for Galactic Herald: How NASA Communicates Space, presented by UTMB (University of Texas Medical Branch). Today, we’re going to hear from NASA Johnson Space Center Public Affairs Officer Gary Jordan, NASA Exoplanet Exploration Program Office Public Outreach Lead Thalia Kahn, NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory Public Outreach Lead Kaitlyn Soares, and NASA Goddard Spaceflight Center Producer Michael Starobin. Our first presenter, Gary Jordan, is a public affairs officer at NASA Johnson Space Center. His responsibilities include managing public messaging and media relations for commercial low-Earth orbit development, Commercial Crew and the International Space Station. Leading the digital multimedia content team, hosting live television commentary of dynamic spaceflight in Mission Control Houston, and producing the very popular show and hosting it, “Houston We Have a Podcast.” Our second presenter, Thalia Khan, is the public outreach lead for NASA’s Exoplanet Exploration Program Office. She engages the public with exoplanet science through producing creative products, organizing public and science events, coordinating communications activities across the theme of exoplanet science, missions and technology development. In addition to her communications role with ExEP, Thalia provides support for NASA’s Universe of Learning education cooperative agreement. She provides informal science institutions with resources to educate the public on general topics of astrophysics. Thalia has a bachelor of arts and communication and is currently finishing her master of arts and communication at Johns Hopkins University. Our third presenter, Kaitlyn Soares, is passionate exploring the convergence of art and science and how the relationship between those subjects can serve the public. In her current role as public outreach lead for astrophysics at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, she translates data through a creative lens that improves access and perception of complex scientific information. Before joining NASA, Kaitlyn managed digital strategy for art and cultural institutions in New York and Boston. She has a master of science in communication from Boston University, is currently earning her master of business administration at Boston University Questrom School of Business. Our fourth presenter, Michael Starobin, is a senior producer for television and multimedia at the NASA Goddard Spaceflight Center. For the past year he’s focused exclusively on work as the producer and director for live events about the James Webb Space Telescope. Michael has reported on and off camera for NASA on a wide range of missions from locations including Greenland, Japan, Canada, Chile, and Antarctica. He’s developed speeches and presentations for NASA administrators and center directors, as well as led numerous high level media initiatives at the mission level and the directorate level. Welcome to all of you. Our panelists will now provide more information about their backgrounds and the scope of their work. Then we’ll launch into our conversation. We’ll first hear from Gary.

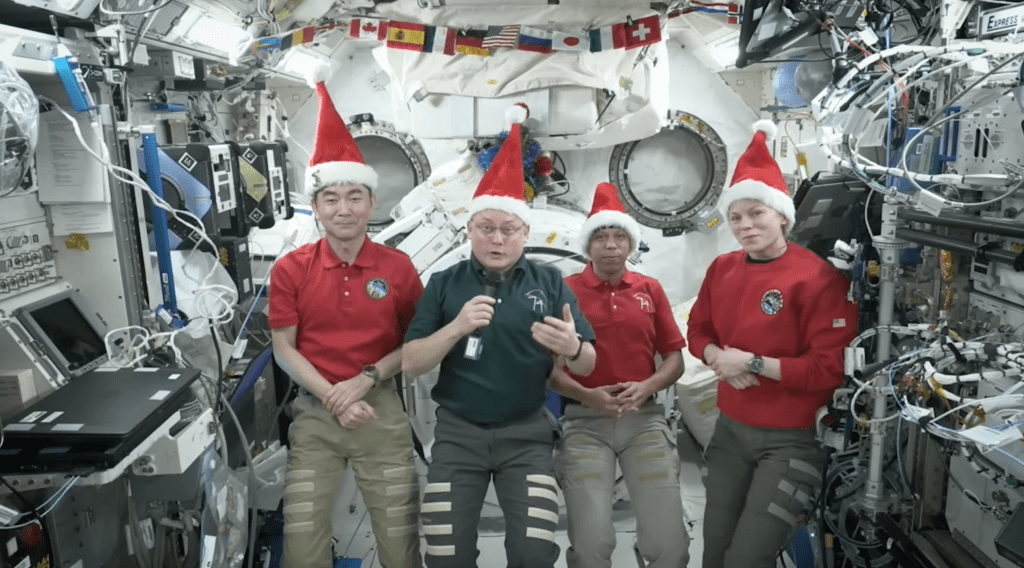

Gary Jordan: Hey, thank you so much, William, and I am certainly honored to, uh, be a part of this panel, so many talented people that help to share NASA’s messaging. And so I wanted to talk a little bit about what I do at the Johnson Space Center, what our team does really, to communicate namely human spaceflight. And I wanted to kick it off by sharing sort of the message and, and, and the charter that is instilled within all of us, all of the panelists that you see today. It is really the purpose of why we’re communicating. Um, and then of course, we’ll get into how we’re communicating. This is, uh, section 203 of the Space Act, and it truly is, it is our purpose, it is our charter, and it reads, “to provide the widest practicable and appropriate dissemination of information concerning its activities and the results thereof, and to enhance public understanding of and participation in the nation’s space program and in accordance with NASA strategic plan.” That language really says that we have to communicate our message to a mass audience and make it consumable and understandable; so, namely the U.S. taxpayer, has full understanding of exactly what we’re doing. The NASA strategic, uh, plan is really the, the tactical approach, the strategic approach, of how we do that and to the various, uh, audiences that we’re communicating to. So I’m going to go through a couple of examples. One of my favorites, of course, is, uh, “Houston We Have a Podcast.” This is sort of a passion project of mine that came, that was born out of the fact that I moved into the downtown city of Houston and my commute down to the NASA Johnson Space Center went up to about 45 minutes. And in that 45 minutes, I needed to buy some time. So I wasn’t necessarily listening to the radio and I discovered podcasts. Naturally, I was looking for a NASA podcast or a space podcast to tell me about what was going on and I couldn’t find one. So I thought we’d make one. It, the format is really a long-form conversation with a NASA expert about a specific topic. Um, what I like to think about it is, it’s a way for me to trap someone and ask them questions that I’ve always wanted to ask them. Um, I love doing it, and it’s certainly a unique way of reaching out to a new audience that has proven to be, uh, quite popular. When we started we were about, we were the second real podcast, the only other one, uh, at NASA, at least. The only other one that was out was “NASA in Silicon Valley” telling stories that was happening there. And then the rest of the NASA podcast, suites of products, was really just repurposed videos and, and other products. Um, so this sort of kicked off, uh, uh, a movement, really, where we see a lot of, uh, if you go to NASA.gov/podcasts now you’ll see a lot of great content from other centers and, and, and the agency having its own enterprise podcast represented. And there’s a lot of stories to tell. Um, it’s been a unique way to communicate what we’re doing to an audience and really dive deeper than we’ve ever done before. But it’s not necessarily the only way that we do it. Um, one of the ways that I really enjoy communicating the message is through live programming. Uh, I can’t quite take credit for Launch America; it was a massive project. Um, but I certainly had a minor part in building, uh, what it is today. Launch America is the effort that we’re taking here at the Johnson Space Center, and really across the entire agency, to share the message of why it’s important to launch crew from the United States on U.S. commercial vehicles, on U.S. commercial rockets. Um, it’s a movement that’s going to lead into, I think, some discussion we’ll have later about what it means to build a low-Earth orbit economy. Um, but Launch America is the communication effort — the brand, really, that goes behind our live messaging. I’m sure Michael, when we get to his, uh, description, uh, on what he did for the James Webb Space Telescope, it all fits in with branding and trying to tell the story. And so, Launch America was branded a certain way. So you see here this is just a, a screenshot from what is really continuous coverage, from pre-launch, uh, through the duration of a capsule’s flight with the crew inside until it docks to the International Space Station and the crew enters. So it’s quite a long program that we have to run, but we have hosts, we have a graphics package, we have a certain style, and we have participation, uh, from really several different centers as well as the commercial, uh, partner that we are with. In this case, what we’ve seen, uh, historically for the past coming up on two years now, almost, uh, even more than that, is a joint broadcast with our commercial partner SpaceX. Uh, and we tell the, the same story. How we’re telling the story is through, of course, the visuals, but it’s a pretty complicated story to tell through all phases of flight, human spaceflight is not necessarily easy. So we created graphics packages from the ground up to really tell exactly what’s happening and show it, too. We build these packages that can be previewed ahead of an event as well as is during the event itself, really guide the viewer through a mission and, and really engage them. So, so when they engage and it, it is truly an engaging event, it’s not necessarily a live broadcast, we are talking through social media, that they have full awareness of what’s going on. Visually, it’s super-important to make sure that we are telling the story together. One of the thing we built up from the ground up is not to do two separate broadcasts. When SpaceX started up and started sharing the messages on their, uh, of their efforts and whatever they were doing at the time, they of course built up their own infrastructure from the ground up on a SpaceX webcast. And we, uh, broadcast live on NASA TV. It was super-important that we were able to come together and come up with an agreement on how we can tell that story together. Uh, so you can tell, we have hosts that are able to share this story very passionately. Um, we obviously tried to bring a passionate and, and – a face, a good face that can tell the information. Of course, space — of course, they had a hard, hard time finding a good face from the NASA side, so I had to step in. But the important thing is that NASA and SpaceX, you can see as this image, are together, uh, the SpaceX NASA and the NASA logo is an important story to tell. And that messaging is really at the ground level, that this is a joint effort. We’re doing this together and, and we are accomplishing this together. It’s the only way that that can happen. A little bit on the less-fun side, but equally important is when we’re sharing the messaging is who we’re sharing it to. Now, a couple of the first examples I’ve mentioned — the podcast and the live broadcast — is meant for truly what the charter is, a mass audience, but it’s not necessarily direct to the mass audience every time. Sometimes we have to go through the media and the media, of course, do a great job of amplifying the stories that we tell. So we design events specifically for them. Right here is an example of a live broadcast that we’re doing during COVID times. Uh, so it is, look, it does look a little bit unique. You meet, even, even as we’re doing this today, we’re all remote, we’re all in separate locations, so we have to bring in all of these great, uh, talent from, uh, and, and leaders from the agencies, NASA and SpaceX, and the European Space Agency, bring them together and share our story. Um, it’s been challenging of course, to do during, uh, COVID times, but, uh, it is very important that when we share this messaging, we do it, we make sure we are including all audiences. So that this is an event that’s specifically meant for media. We put the leadership in front of media, and they have the opportunity to ask questions and we bring everyone together. Again, having us safe, side by side, telling the same story, is very important to the mission. We’re all in this together. This was a briefing, uh, that was specifically for a Commercial Crew mission. So it includes U.S. industry, it includes the U.S. uh, space agency, NASA, and our partners, the European Space Agency, who were flying an astronaut on board. Into some of the more fun things. We get to explore unique ways to reach out to new audiences. Not everyone is a space fan, but we want them to be, we want them to know what’s going on. And sometimes we have the opportunity to dive deep into a subject like we do at the podcast, that’s really meant for, for space fans. But how do we engage those folks that are just new, and they don’t know anything, and we want to build them from the ground up? So we’ve explored unique ways of doing that. And sometimes we, we, uh – we build videos, uh, that are specifically meant for new audiences in ways and styles that are very close to what you would see on, uh, a social media platform. Uh, I have the privilege of leading a group that does just that. It’s a small tiger team group that thinks about unique ways to reach out to new audiences, um, in ways that NASA typically doesn’t, and, and then we explore it and then we try new things. Uh, this video, uh, is called “Everything About Living in Space”; I hope you check it out. Uh, it’s a video of, uh, astronaut Reid Wiseman walking around one of the mockups we have at the Johnson Space Center and showing everything about the, about the space station that he lived on for about 165 days. And he answers a lot of questions in a very short amount of time. We’ve also created a suite of gifs as part of the same group. Um, they are reactionary gifs. So if you are looking up a reaction to something and you just type in the word “NASA,” we are part of your conversation. Um, something that’s more of an introductory thing, right? So we can, if you’re talking about space you have a way to engage, you have a way to connect a very purposeful statement, right, it, it, but it is a way to introduce you and involve you as, as a listener and as a participant in what we’re doing at NASA. Early on in my career, uh, this is sort of what kicked off the group that exists today is, I had the opportunity to create a fun music video called “NASA Johnson Style.” I hope you get to check that video out. Um, it was singing and dancing following the trend at the time, back in 2012, that was the Gangnam style trend. Uh, a lot of people made parody videos, but as a student, we got to explore new things for new audiences. And we were of course, the, the right people to do so because, um, we, we were also new. So we were trying to engage, um, really peers, colleagues, uh, and we tried this new thing. It, it caught on very quickly, became very popular. And so, that’s why we’re doing some of these continuing efforts today, uh, is because, uh, NASA, uh, saw some value in that. Uh, we can get into this more, uh, when we have a discussion, but it’s not all fun and games, and of course there are limitations. One of the unique limitations is that NASA, we as an agency cannot advertise. So how do we get our messaging out without doing paid promotions, without tying with different brands and amplifying in ways, uh, as a, as a marketing professional would? It’s very unique and very challenging in its own way. The media guidelines are very searchable online. You can check them out. I’m not going to, I’m definitely not going to read them to you, but there are, are significant limitations to what we were able to accomplish, or what we were able to do. But we still accomplish great things. Just like, uh, being able to put the NASA brand on a pair of shoes, another unique way of engaging and, and sharing, uh, the NASA brand, having people, uh, to engage by wearing a brand, by, by making it an extension of their own identity. Uh, this is a partnership that we made with, uh, Adidas. I was more at the ground level, I wasn’t at the execution level, um, but, but it was a partnership based on some research that Adidas was doing and wanted to amplify on their brand. And so, even with some of the restrictions, we find very unique and interesting ways, uh, to share our story. So William, I’m very, I’m very honored to be a part of this, uh, panel, and I’m very excited to hear what some of the other panelists have to say. Um, and I hope this, this is a really good intro, this is a really good introduction, to the great conversation we’re about to have. Thanks for having me.

William Harris: Great, Gary, thank you so much. I was wondering who was behind NASA Gangnam style? You know, we’re still actually using that video as some of our education programs, by the way. So let it, so, you know, it has had a, a shelf life that’s pretty significant of over a decade.

Gary Jordan: I, I was part of a small group, but I directed it, edited it and filmed, and, and then I had a bunch of other talented people help me out as well. Um, it was a group effort, but it’s, it’s certainly, it’s certainly still around. That’s very good to hear.

William Harris: Yeah. It, it really is. It’s a lot of fun. Thank you so much. Can’t wait to dive into more questions with you. Now, we’ll hear from Thalia Khan. Thalia.

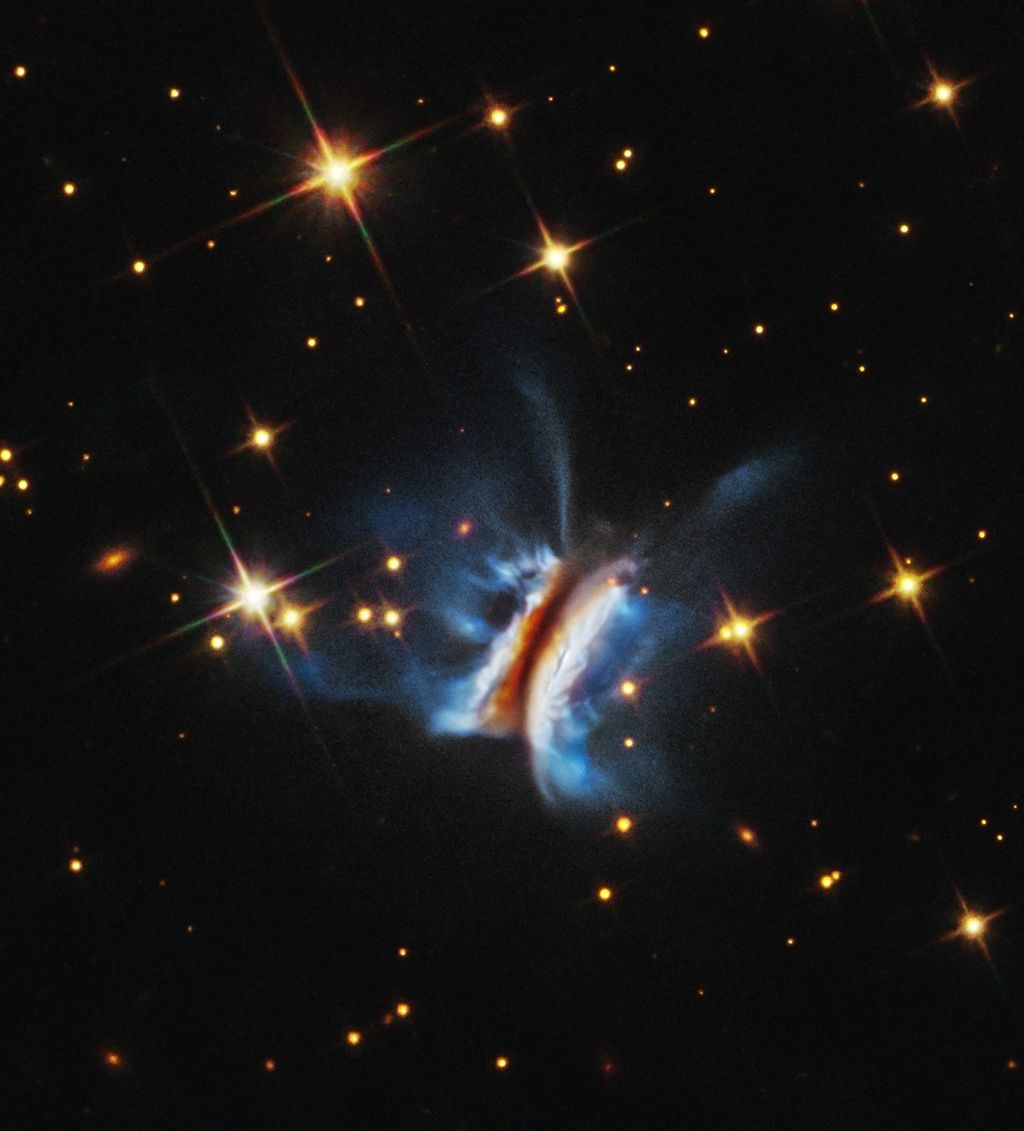

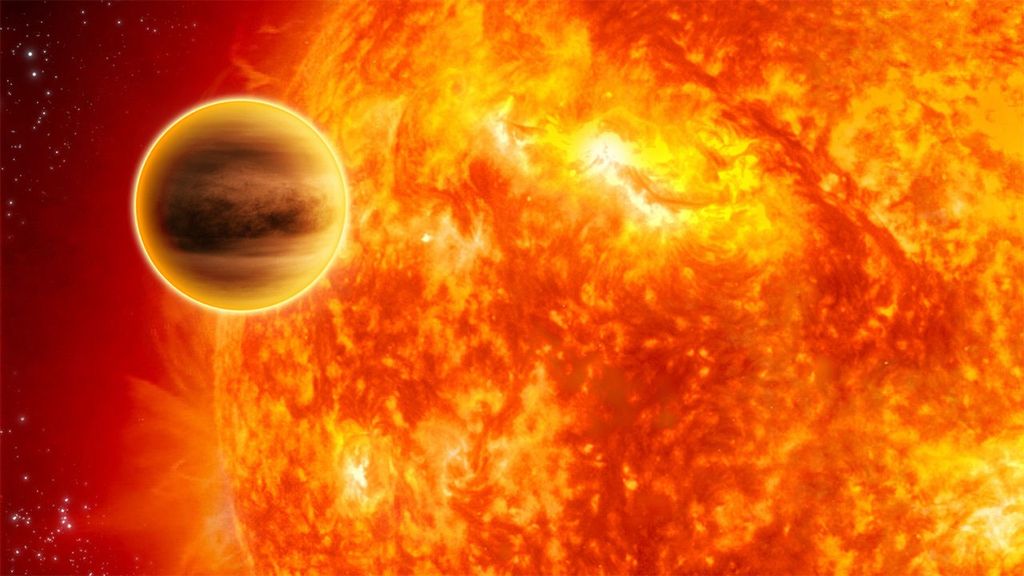

Thalia Khan: Thank you, William. So, fantastic, uh, presentation, Gary. I think when a lot of people think of NASA, they really do think about astronauts and going to space and rockets. Um, and it takes them a little bit of time to understand that, uh, NASA is more than just astronauts going up into space. Um, so there is a universe of, uh, discoveries being made every day, all the time. Um, and so I’m here to talk to you a little bit about the communications that we do for exoplanets, which are planets that are outside of our solar system. So I work for NASA’s Exoplanet Exploration Program office. I get to talk about the discovery and characterization of these alien planets, or these alien worlds. And, and so when people think of exoplanets, they think of maybe planets that look like Earth or planets that look like Jupiter, but what is really a challenge about communicating exoplanet science to the public is, um, exactly what you see right here. This is what we know of exoplanets. Uh, when we talk about observing exoplanets, um, or, um, you know, studying exoplanets, what we’re really studying is lines on a graph. So this right here, um, is a demonstration of an exoplanet light curve. This is where we get all of our information, um, from when an exo — from what an exoplanet could potentially look like, how big it is, how long it takes to travel around its star. Um, so there really is a challenge in trying to communicate to the public what these places look like when we can’t even see them ourselves. So my team has actually, um, taken on the, this challenge, um, and we have discovered different ways to get this science in front of people to make it more relatable. Um, we created this series of posters, uh, called the Exoplanet Travel Bureau, where we get to imagine worlds that we would, um, like to maybe live on. Um, so as you can see here, we have a bunch of different, uh, snippets of posters. We have planets where, um, there are seven other planets in the system and you can see them in the sky from whatever planet you’re standing on. We have a planet where it’s entirely covered in an ocean of lava. We have a planet that we discovered orbiting two stars, um, and we nicknamed it Tatooine. And so, the travel bureau was actually taken, uh, by some folks over at Goddard and made into a video. Um, you know, we are trying to make science accessible to as many people as possible and by doing so, we try to reach people who may not already necessarily be interested in science or astronomy or NASA. Um, and so by creating videos and creating, um, basically travel advertisements, we can get people to get interested, um, we can spark their curiosity and we can get them interested in learning more. So next up, we have a video, um, of the travel bureau planets.

[Video plays/Music]

Thalia Khan: So it takes a lot, um, for us to take, uh, abstract concepts or very technical topics and be able to make them accessible to the public. Um, but we’ve done that through developing really, um, captivating materials, such as posters. And so here is an example of a project that I worked on. Um, I just want to talk a little bit through the process of getting to work with some of the brightest minds, uh, in the world. Um, and here you can see the sort of, you know, rough concepts at the beginning, um, to maybe a near-final draft of a poster. Um, this is 55 Cancri e, it is a planet, um, that is completely covered in an ocean of lava. And, um, the reason I show this is because I want to show that it is an iterative process to create a lot of the content that we create. Um, it takes a lot of going back and forth with scientists, with engineers, with experts in the field, um, to walk through what some of these, uh, planets may look like. And because we can’t see them we have to have, heavily rely on, um, you know, educated guesses or, um, a lot of the data that we collect and how scientists interpret it. Um, so you can see from the left-hand side, we have a planet, um, that has a surface; we have a train going through it; um, and then on the right-hand side, you can see that we no longer have a surface on the planet because, um, throughout the process of developing this poster, we discovered it was too hot to have a surface. Um, so this is just an example of some of the materials that we create. And you can see that not only do we try to communicate the science behind exoplanets, but we also try to communicate the missions that discover these planets. This is from a series of posters that is dedicated to highlighting telescopes that discover exoplanets. So this poster is actually the test satellite, and it was a really fun project to work on because it really brought the science community a lot closer to the public. Um, and it is really a great connection between, um, you know, what the science community finds very exciting about, you know, sending a mission to space and what the general public could, you know, potentially learn about these missions. So it was a really wonderful way to connect, um, I guess our audience and then our science community. And this is the series of posters that you can download on our website, exoplanets.NASA.gov. Um, and we highlight all the telescopes that are in space, because they don’t ever leave space. You know, we get to talk a little bit about what makes them so fantastic and how they really expand, um, our view of the universe. And so aside from creating really engaging content that we get to publish online and share with our audience, um, we also get to organize, um, and support events where we get to reach out to people, um, where they are. And I think that’s something that is very, um, important for a lot of, you know, communicators at NASA is reaching people where they already are. Um, you know, we really want to engage people who may not even know that they’re interested in science or know that they’re interested in STEM (science, technology, engineering and math), so we do spend a lot of time trying to reach people at events like South by Southwest, Comic-Con, the LA Food Fest. And we also partner with, um, like the Hispanic Heritage Foundation to reach, um, typically historically-excluded audiences from STEM. So that’s something that’s very important to making science accessible for all. Um, and we do that by, um, making partnerships, and we also do that by translating a lot of our products into different languages, such as Spanish. And, um, these are some snapshots from some events that we’ve done in the past. Um, and this is really where I draw a lot of my inspiration from. So as a young, you know, kid, I was always really interested in science, um, and STEM. I wanted to work at NASA. I wanted to be an astronaut. Um, but, um, I didn’t know that you can do that. And so being able to meet people in person and engage them in science and STEM and open up their world to the many wonders of the universe has been incredibly rewarding. Um, and being able to, um, go to work every day and help educate people on science and astronomy and exoplanets, um, you know, keeps me inspired to keep doing what I’m doing.

William Harris: Wow. Thank you so much, Thalia, that was fascinating. I love those travel posters. I’m ready to go kayaking on Titan. That was quite enticing and that really does stimulate your imagination. Next, you’re going to hear from Kaitlyn Soares. Kaitlyn.

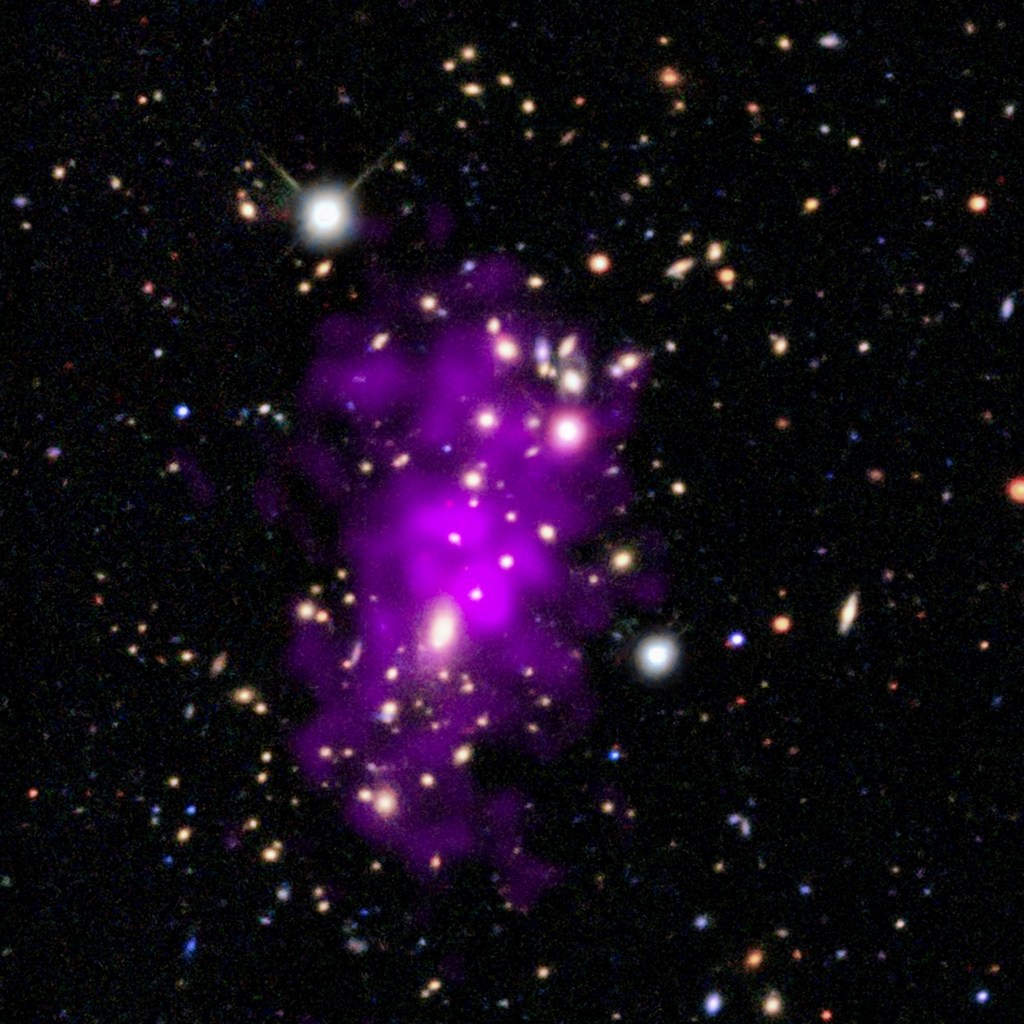

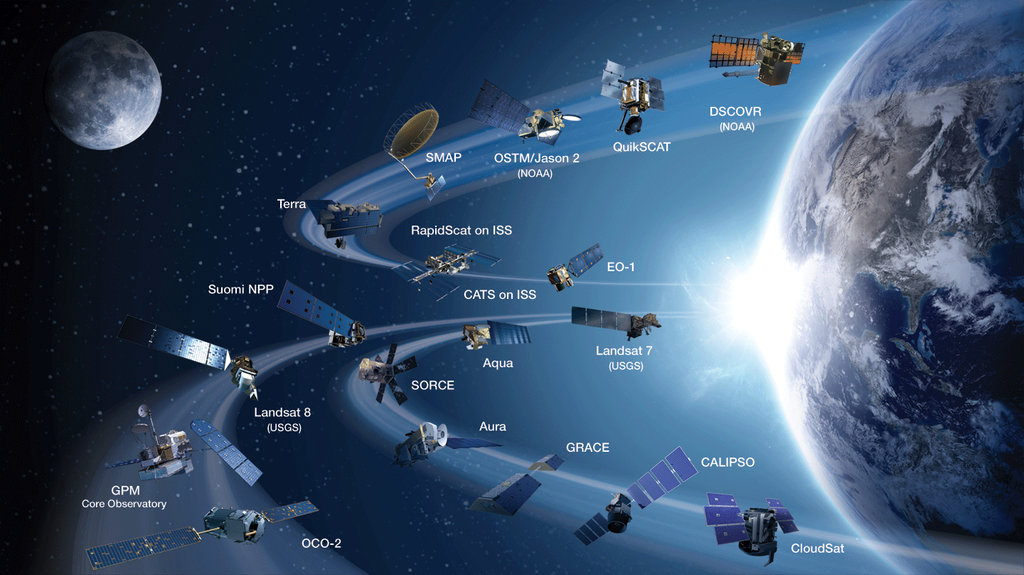

Kaitlyn Soares: Thank you, William. Um, hi everyone. I’m Kaitlyn and I’m a public outreach specialist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory with Thalia in Pasadena, California. Um, I wanted to introduce myself today by taking it back a few decades. Um, so one of my most vivid memories as a little girl was, uh, seeing the Moon through a humble telescope in the backyard of my childhood home. And from that moment on, I was hooked on space and I knew I wanted to work at NASA. But for a long time I thought NASA only hired people who were good at STEM subjects. I can confidently say that I am not gifted in math. [Laughter] My professional talents lie more in the communications and the arts. Um, so those are the subjects I focused on earlier in my career. Um, luckily though, through NASA’s outreach efforts, I discovered that NASA hires communicators like artists and photographers, designers and writers, um, to tell our stories beautifully and comprehensively. A picture here is my colleague artist, Kat Park. Um, she is sketching visuals for a mission called SPHEREx (Spectro-Photometer for the History of the Universe, Epoch of Reionization and Ices Explorer), which I’ll talk about in a moment. Um, so now that I, I work with the agency, it’s my responsibility to ensure that the convergence of science and art can be harnessed to reach as many members of the public as possible. Uh, in my role, I specifically lead outreach for NASA’s astrophysics missions and other astrophysics projects managed by JPL, many of them pictured here in this image. It is my job to be curious and ask some of the world’s most brilliant astrophysicists to explain their science to me, so that along with my team we’re able to translate and communicate it to the public. Um, and it is such an exciting time for astrophysics at NASA right now. Um, so over at JPL we led the construction of one of the main instruments on the James Webb telescope, pictured here on the left. Um, James Webb is NASA’s newest great observatory that launched this past December. Um, the name of the instrument we constructed is MIRI, or the Mid-Infrared Instrument, and it will help the Webb telescope see objects like distinct galaxies and newly-forming stars. Um, as the Webb telescope gets positioned and calibrated to start observing the universe, um, the buzz continues to increase in the astrophysics community, of course, uh, but also with the public who have been following the telescope’s journey for years, thanks to NASA’s dedicated team of science communicators. At JPL we’re also developing a mission called SPHEREx, which will perform an all-sky survey. And what that means is that this small, but mighty telescope will map about 99% of the celestial sphere, or the entire sky. Um, by comparison, Hubble has observed about 0.1% of the sky, I believe. So in, in doing this SPHEREx will help astronomers and other scientists investigate some of the most profound questions humanity has ever asked about the universe. Um, these are question like, how did the universe behave in the milliseconds after the big bang; um, what are early planetary systems made of and how do they form; and how have galaxies evolved over the life of the universe? What does that mean for the fate of our own galaxy, the Milky Way? Um, so clearly I, I love space telescopes, but the, the process of working with these missions and taking the complex, uh, almost ethereal scientific goals they aim to achieve and making them accessible to you is my goal when I wake up every morning. And one of my favorite projects I’ve worked on to date is called NASA’s Galaxy of Horrors series, which was the brainchild of my partner Thalia here. Um, it is a poster and video series that showcases some of the scariest astrophysical phenomena in the universe and presents them as movie posters. So here we have dark matter and dark energy, which are two completely different phenomena despite their similar names. Dark matter is an invisible material that scientists believe makes up roughly one quarter of matter in the universe. The only way that we know this actually exists is because we see its gravitational effects on visible matter, uh, things like galaxies. So dark matter pushes and pulls visible matter much like a spider might weave a web. And we know that dark matter is mysterious. It’s a little scary. So the poster on the left is how we chose to interpret dark matter artistically for this series. Dark energy on the other hand, is, uh, relentless force that is causing the universe to expand at a quickening rate, like a vampire bat expanding its wings and clearing anything in its path. Um, so scientists believe dark energy will continue to push galaxies farther and farther apart causing the universe to become colder and darker over time. Uh, it takes a team of at least six people to create these posters. Um, I’m the producer. We obviously have the artists, we have a copywriter, an art director, and a team of scientist-advisors who help us. Um, in most cases we also hire translators as well. Um, all of the posters and graphics that our team creates are produced in both English and Spanish, Spanish, of course, being a top language spoken in, in the United States. Um, so we, we also write bilingual alt-text for all of our products, so anyone who cannot see these products can still learn about the science that they convey. Um, all of our art and our explainers and our resources are available for free on our website, which is exoplanets.NASA.gov. Um, you can download our files from home or your local library. Uh, it’s truly our purpose to create things that captivate the science-initiated, the science-interested, um, and also people who might know nothing about astrophysics and be completely taken by surprise when they come across our black hole poster and learn that there’s a super-massive black hole lurking at the center of the Milky Way. Uh, so with all of that being said, um, it’s an honor to join the panel today with my talented colleagues, um, and thanks as well to the space center for the opportunity to share our work with you today.

William Harris: Great. Thank you, Kaitlyn. You must have a lot of fun coming up with these bylines. I like is when it’s dinnertime, you’re the meal; a lot of fun. [Laughter] Great. And now we’ll hear from our final panelists. Michael Starobin. And Michael, I’m very much looking forward to your presentation.

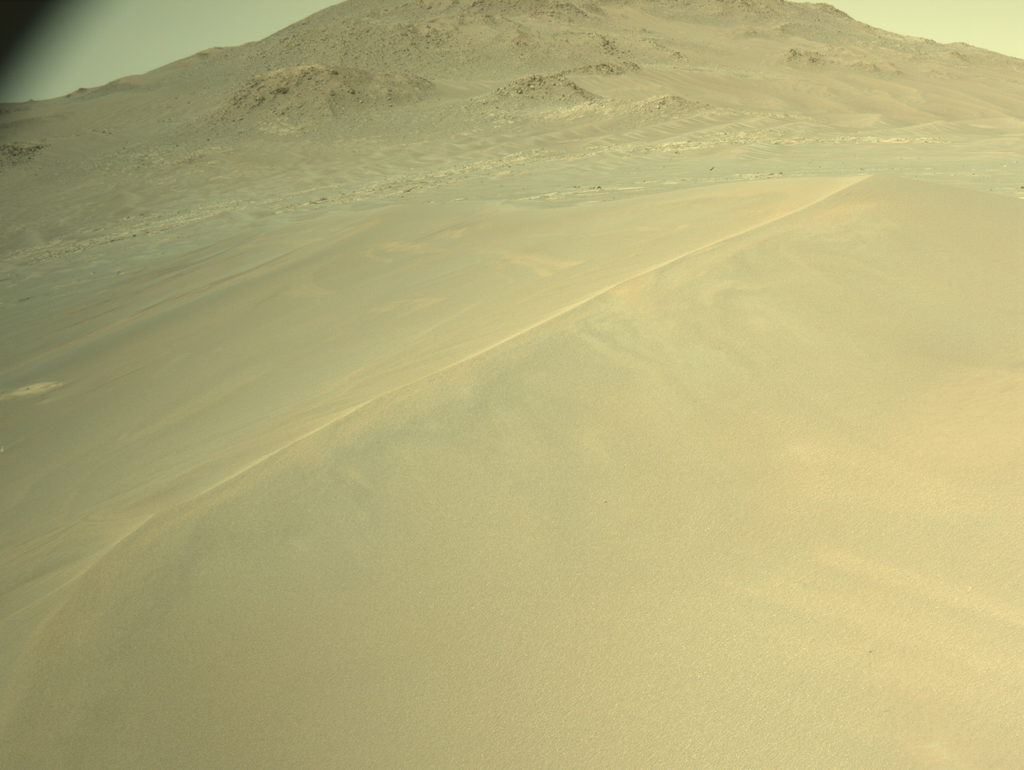

Michael Starobin: Hi, it’s really great to be here. Thank you, William. Um, as you gather from my colleagues, uh, there’s a theme here is that NASA is not just for scientists and engineers, even though NASA is, of course, a science and engineering agency. And it’s really, uh, very satisfying, uh, coming to NASA as someone who is also not a scientist, as my colleagues have suggested. Uh, I am a filmmaker, and there is a range of skills and tools you have to bring to the position which are sometimes atypical. People in the general public often think of NASA as astronauts, of course, big rockets, and occasionally a robot on Mars. Um, but a lot of people don’t know about the science that we do, the things that, uh, look at the atmosphere, the weather, uh, how airplanes work, how do you build esoteric pieces of hardware which have real and material impacts on what we know about the world, the universe, uh, how everything functions together. And that process of storytelling makes this a possibility for general audiences, but for us as the creators it’s a moment of translation. How do you take often specialized languages, and using words and pictures, find a way to communicate it in non-technical language? And this past year I had the privilege of trying to translate one of the largest missions that NASA has ever done in pure science, and that’s the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope, as you’ve heard about this already, uh, in this presentation. Webb launched on December 25th from French Guiana, it’s a launch site in the jungles of South America. It almost feels like a science fiction novel. NASA launched the James Webb, uh, there because our European partners have an extraordinary rocket called the Ariane 5: it’s very large and it’s able to carry this massive, massive telescope. Now I’ve been chasing this telescope for years, uh, all over the country, including at the Johnson Space Center, at its main fabrication location at Goddard, and also in, uh, in California, where it was being built at a facility, uh, in its final stages. And it is exceedingly complicated to try and present how does this all come together for launch, and to tell the story in a live event I had a massive team working with me — over 30 people in a live show, people overseas, people in Baltimore at the mission operations center at the Space Telescope Science Institute. It’s a lot of pieces to wrangle. It’s like a real-time film that you were directing to tell this story. But while Webb has been a thrill to be a part of, it certainly is on the far side, the extreme side, of the kind of storytelling that we do. It’s rare that I will get a crew that large for that long who are going to look for direction on how are we going to build pictures and, and interviews and all of the components, live-action videography, I worked with a fantastic, uh, colleague and, and many other people to develop those, those tools. But there are other stories that we do as well. Many of my stories are very small. They have to be translated. And then you are a one-person operation. Astrophysics is inherently a romantic discipline: you’re looking out into the universe, often at beautiful objects. You’ll never see them in person. You’ll never reach them yourself. So they’re inherently romantic in a poetic sense. But climate change, or how does rain affect energy circulation in the atmosphere, always feels ordinary. You walk outside, rain falls on your head, you’re wet. It doesn’t feel like a moment of scientific thrill. And the challenge is, if you’re a one-person producer out in the field, how do you take NASA data and make that story come alive? So you have to have the soul of a poet to do this, and a bit of a, of an intrepid, uh, Indiana Jones, uh, mentality sometimes. As you’re looking here, I’ve been in exotic places around the world. Uh, in Kangerlussuaq, Greenland, I spent a month flying with a hotshot team of scientists and engineers, very, very low over the Arctic ice sheet, uh, taking measurements, uh, as we watched the mass balance of ice change, something fundamental to study in climate change. And that mission continued doing overflights, uh, in Antarctica, uh, flying over the South Pole but also some of the ice sheets around the edges of the continent, taking similar measurements. This is critical, um, to determining where the planet is going and how it’s going to evolve. And often in doing this, you’re on your own. You don’t necessarily have the ability to get things fixed. You don’t necessarily have the opportunity to have a warm place to sleep at night. People think of NASA as having all of the resources in the world, but if you’re a storyteller in the field, over ice, it’s you, whatever cameras you could carry on your back, and whatever clever solutions you can find. And you’ll be lucky if you can find a hot meal at the end of the day. And if that’s not interesting, it’s probably not for you. I happen to find it kind of thrilling, and I know that this is the extreme to the giant productions of leading something like Webb. It’s just as exciting to have to say, how am I going to tell this story on my own? Sometimes you don’t know what you’re going to encounter in the, uh, image in your upper right, you see I have a penguin that’s standing onto some of my camera boxes as I’m talking about climate change. Turns out it was an animated penguin, but sometimes you get to deliver unexpected resources in the service of telling a story. Most of the time, though, it’s you at your computer with words and pictures. It’s often a very quiet internal space, except when you turn the volume up. Webb is an extraordinary experience. Again, a massive crew on a sound stage telling the story in real time, this is a comfortable space for me as a film director, but it, but most days of the week, in most days of the year, you’re writing, you’re editing photos, you’re editing video, you’re making things come together that otherwise are only in your mind. And that’s where the theater of this is. I would suggest one, uh, other thing about how to tell complex stories. I would say that stories themselves are more important than the atoms we know in the universe. Stories are more important than atoms, but there are endless atoms in the universe. There are trees and cars and rocks and people, but it is only in the collection of them in context that we begin to find meaning. There’s no way a video I do about Webb is going to make you an expert in Webb, but it is by placing context around the engineering, the construction of the mirrors, the reason for their position on the architecture of the unusual shape of the telescope, that you begin to appreciate some of the nuances of something that other people have spent their entire careers on. So the context of how atoms fit together is what we as storytellers are responsible for doing. We add that context to how atoms are assembled. I would show you one image here. This looks to you like the Earth, but I’m going to assert actually it’s not the Earth. My assertion, it’s not the Earth because this is composed of data. There is no camera that can capture this image. The last time humans took this picture was in an Apollo capsule many years ago; there’s only one satellite, or spacecraft, actually, called DSCOVR (Deep Space Climate Observatory) launched in 2015, that’s capable of this vantage point. So how do we see this image? We build up layers of low-altitude orbiting spacecraft around the Earth, there’s land surface and the cloud layer and the city lights layer, which you can barely see in the shadowed part of the globe. This, the dividing line between day and night, which we call the terminator, has actually been artificially calculated in the computer. And that blue stuff, the ocean, is completely fabricated because you can’t really see blue ocean from space, it appears mostly black. But this contains a sense of Earthness. It conveys what the Earth is for the purposes of communication. And it is based on factual data, real data. We say we made up the ocean, but we know the actual precise outlines of the ocean basin. For the purposes of this image, it conveys Earthness and therefore it helps me tell a story about the Earth. And it’s that abstraction of thinking which is what makes so much storytelling inside NASA possible, because we don’t go to space as storytellers and we don’t launch the telescope as storytellers, but we do find the abstractions that make you, a non-expert, come to appreciate something nuanced that you might not otherwise have had available. In this next image you’ll see a blue line ascending to the right, and without any context it’s impossible to know meaning; but this blue line is critical for climate change research. It’s based on rigorous data, it’s vital in the narrative of climate change. When we add context, we discover this is something called the Keeling Curve. And what this shows in this sawtooth pattern is the seasonal variation of carbon uptake and recession as we watch an overall trend of rising CO2 levels in the atmosphere. Now, if you don’t know what the importance of rising CO2 levels in the atmosphere are at all, the precision of this chart is irrelevant. But if we talk about the context of rising CO2 levels, this suddenly becomes an abstraction, something that can unpack climate change and enables us to have a much deeper conversation that just a pure recitation of data by itself would enable. So my final point is to say that as storytellers, as we look at various movie posters that are created or videos that show tours of various planets around the solar system or music videos that convey a sense of who we are and what we aspire to, it’s important to recognize that each of us are bringing a sense of abstraction to the narrative in order to present something that’s beyond just the recitation of data itself. I’m looking forward to questions; uh, it’s very exciting to be part of this panel.

William Harris: Fantastic presentations by all of you. So interesting what you have to comprehend in order to interpret to the public, uh, the complex and amazing science that NASA has underway and with its partners. I guess I wanted to begin with Gary, because it is a new territory now for NASA to be collaborating with commercial partners in co-presenting, and you have two different brands who are, uh, have, you know, similar goals and objectives but different ways of presenting things. How do you determine the key messages that you are going to convey when you’re working with a commercial partner, say like a company like SpaceX who is now, um, transporting astronauts to the ISS?

Gary Jordan: A really good question, William, and, and that was certainly a challenge. Um, it, it, we, when we started we, of course, to your point had different messages, had different stories we wanted to tell, um, but after, you know, a lot of months and, and just, uh, constant meetings and efforts to really talk about what those were, you find out that actually we are all part of the same team and trying to do the same thing, communicate that same message. And then over time it became easier to actually write it out and say, this is, you know, this is our parts together, this is our mission. And really it wasn’t, you know, to an extent there is, you know, here at NASA we this is our goals, here at SpaceX, this is our goals. But what we found is that we were all sharing in the same thing. And this is actually true when we work with our international partners, too, um, when we tell the stories of science and, and what we’re doing on board the International Space Station, the collaboration to make that, uh, that complex what it is and to continue it, uh, now, you know, extended to 2030. It is all because we are trying to do the same thing. We’re trying to explore, uh, we’re trying to do new things, um, and we, and in order to do that we need to come together, and everybody’s messaging is the same. So we, when, when it comes to commercial, uh, it’s going to be a new world. It, we’re developing it right now. My, my, my main job right now is, is actually, I’m working very closely with Axiom and SpaceX, uh, to develop what the show for the first private astronaut mission to the space station’s going to look like, which is new in its own way. It’s different from what we do for Commercial Crew missions, which of course the objective is to take government astronauts up to the space station. Now we’re taking private astronauts. So what’s the messaging there? Everybody has to play a part, so how are we going to, how are we going to construct it? Um, but it is progressing in a positive way and it’s setting the ground for truly what the future of low-Earth orbit is going to look like. It’s going to look like government astronauts, international astronauts, and commercial astronauts all working together. And so, I think that that platform of having our messages synchronized to tell the same story is really going to continue.

William Harris: That’s great. Well, I’m very curious, uh, Thalia, I’ve worked with many scientists over the years, and I know that they often can be quite literal. And I think, uh, both you and Kaitlyn are using kind of graphics and representation that really kind of press the fabric of kind of, if you will, kind of technical representation, uh, tourism, of course, in other planets. Um, but I know that sci-fi is a really important way to enthuse people about science and often it leads to innovation and creativity. How do you strike that balance, working with the scientists at, at JPL to get them to buy into the imagery that you’re trying to convey to create enthusiasm for people to understand exoplanets?

Thalia Khan: Well, it’s definitely a fun process. Um, I, I think there really is, um, we really have to make the effort to strike that balance because I think sometimes it doesn’t come naturally. Um, right? I don’t have a science background so I have, um, you know, to really try to understand, first of all, you know, the science that I’m trying to explain. And trying to get, um, some of our more technical thinkers on board with some of these really, um, fun, uh, you know, sci-fi-ish projects is, is definitely sometimes a challenge. Um, but more often than not we do get a lot of our scientists and a lot of our engineers and a lot of our experts who are just really excited to be able to tell the story of their science, um, you know, whether it be a new discovery that they’ve made or an area where they’re really pushing, um, you know, the boundaries of exploration. And so being able to, um, balance, I guess, more technical, uh, thinking and minds and trying to make sure that, um, you know, this is their science, right, this is things, these are, uh, topics that they’ve spent decades researching and studying, and so, um, being able to find, um, I guess that sort of soft spot where they’re comfortable with, you know, what some of these really, uh, fun and imaginative products look like, um, is definitely something that we have to work on. But, um, more often than not our scientists and experts are excited to tell the story, um, so they’re usually very happy to help and contribute to communicating that science to the public.

William Harris: That’s fantastic. I know, I know that scientists can, and a lot of the JPL and NASA folks, can have a lot of fun with sci-fi. So, uh, fortunately, too, we also have the activities, uh, you know, working with the commercial sector and working with, of course, the private film industry. Um, so Kaitlyn, I’m curious, if you could tell me a little bit about how did, how did you move into this realm of space exploration, interpreting it, because your background is in the arts and you’re, you’re, you kind of have the mesh here of arts with science and, and how did you kind of find that sweet spot for yourself?

Kaitlyn Soares: Sure. Um, I, I think a lot of it just happened naturally. Um, my natural interest as a little girl was outer space. Um, science in general, my mother is a scientist, um, so she really cultivated, uh, that love of learning and curiosity in the natural world in me. Um, but again, as someone who wasn’t, uh, as strong in math, I didn’t really see myself at NASA. Um, so I, I gravitated toward the museum sphere and I worked in museums in New York City and Boston, um, for almost, uh, about eight, eight to ten years of my career. Um, and then, uh, I just, through, through NASA’s outreach, um, efforts, I, I met folks and saw myself in the NASA community. I saw communicators, I saw, um, designers and artists, and I, and I didn’t realize that this was something that NASA did until the outreach effort showed me that. Um, so it was kind of this natural progression where I started in the arts, um, still kind of working in the arts, I guess, but now melding, um, science and art together to reach folks, and hopefully I can bring, um, you know, more talented people into, into NASA to pass on the baton who will take it and see them at the agency someday as a creative or as a communicator.

William Harris: So, I wanted to delve a little bit more into that because all of you, too, have trying to reach, um, a wide range of audiences, very, very diverse audiences, from youth to adults and elderly and people with different backgrounds. Um, what are some of the ways or, or strategies you’ve used to, to reach out to, um, diverse is such a broad word but I guess it is a diverse, you know, people who have different views and perspectives. I know, for example, at Space Center Houston, um, and we’re the official visitor center for NASA Johnson Space Center, we know that 80% of our visitors are what we, are what we call skimmers: you know, they’re people who have kind of an interest and they’re like, well, let’s go to NASA, and they don’t actually really know much about what NASA or Johnson Space Center does. And then we have swimmers and divers, right, the people who really want to get in deep and have a mastery of the basic information. So how, how do you, what are some of the strategies you’ve used that have been really effective to get to those skimmers? Maybe we’ll start with you, Kaitlyn.

Kaitlyn Soares: Um, sure. I think one of the most important things we do in outreach at NASA is working with individuals and organizations who are directly embedded in their communities, um, like the space centers. So science can be more relatable and interesting when it’s delivered by someone that you recognize, either as a neighbor or, um, part of your culture or some other common thread. At JPL and at NASA in general, we work with public schools, museums, libraries, and other local organizations in reaching their communities with space content, where they are. Um, NASA also has a network of about 1200 ambassadors. We call the Solar System Ambassadors. Um, and these, uh, folks are trained and empowered by the agency to host space-related events in their own communities. Um, they’re located in every state, um, Puerto Rico and Guam as well. And, uh, we, we ensure that the products that we make are, are as accessible as possible. We give them to the Solar System Ambassadors, and we distribute them ourselves. Um, but in terms of the language presented, um, abilities and backgrounds of our audiences, we keep that in mind when we’re, we’re creating all of our products. Um, and something I’m really excited to, to deep dive into in the coming months with my team is presenting a nontraditional way of engaging with data from space telescopes through something called data sonification. Um, so we want people to be able to hear stars and galaxies and black holes, to, to interact, um, in, in an audio way with the universe. And NASA already has products like this, but we’re building more of them. And, um, uh, it’s what I find most attractive about data sonification is that we’re presenting a new way for people to interact with science, and maybe we’ll, we’ll pull in some audio nerds, um, or, or folks who might not otherwise be interacting with, uh, space and science in a way that, that we have, um, products.

William Harris: Well, you’ve taught me a new word today: data sonification; that is absolutely fascinating. So, uh, how soon will we be listening to the stars?

Kaitlyn Soares: Um, so NASA already has products like this, but we’re building more. Um, and I’m really excited to, um, start turning some out from JPL, from our astrophysics team. So stay tuned and probably in the coming months we’ll have some more products for you to check out.

William Harris: Well, I want to jump over similar question for, for Gary. Of course, we know the podcast is very popular and of course, I know how to dance Gangnam style, so it was really fun to do that along with the NASA video. What are some other ways, or one of the most fun things you’ve done to kind of reach out to, if you will, a non-traditional audience or audiences?

Gary Jordan: I, I I’d actually say the podcast. Um, and it was because it was a nontraditional audience, and it was a nontraditional method of communication. Like I said, when, when the, when the podcast started, it was really at the ground level, there was only one other true NASA podcast. And so, we were sort of paving the way and exploring a new way of communication that NASA had not truly explored before. Um, so when we came up with the idea for the podcast, I, the reason why I was so passionate about the project is because I was really into podcasts at the time. And I was listening to a number of them. Uh, I think, you know, TED Talk, uh, there was, there was TED Talk, uh, a podcast. I was listening to a lot of science ones, um, Science Vs, uh, uh, Neil deGrasse Tyson’s podcast. But, and all of them, most of them, there was another one, the Nerdist podcast, which is now under a new name. They’re all podcasts that have that long format: let’s just sit down and have a casual conversation. And I thought that was such a unique way to tell the story, uh, that NASA wasn’t doing before. We of course, had the live broadcast, which is probably some of the longer formats that we’ve done, but at the time everyone was really invested in the newness of short form, of the, I think Vine was, was still around when we were exploring the podcast, which is of course, ten second video clips. And how do you capture someone in 10 seconds? This was a way to capture someone in a long-form conversation. And so I wanted to explore that and, and enter into this space and put NASA into this space, um, without necessarily knowing, you know, is this, I, I have a feeling, I had a gut feeling that this is definitely something that NASA can contribute to. How do we differentiate ourselves from what was, um, a exponentially-growing platform? Right now, I think there are a million podcasts. I think, maybe, I might be, overexaggerating; maybe 200,000. It’s, it’s a lot, it’s, it’s an, uh, an extraordinary amount of podcasts. So how do you tell that story? And all of a sudden NASA was in this space that wasn’t there before, and we were part of a story. And I think that really helps, um, introducing it to new audiences. People are curious, they didn’t know NASA was already telling this story, right, I mean, a lot of these things that I’m saying are not new, um, they’re just repurposed in a long-form conversation that maybe people weren’t necessarily exploring before. And that’s just, it, it’s — not necessarily, you know, one of the ways you can reach out to new audiences is find the audience that isn’t, that you’re not reaching out to. Um, the, the podcast audience was one that we were, a space that we were not in, and it was a gap, I’ll say, it was a gap in our communication. So we of course needed to explore it. And I think it benefited.

William Harris: Fascinating. Well, when you said that, it caused me just a quickly look and according to a Google, in 2021, there were 850,000 podcasts. So you were pretty close to that 1 million estimate. [Laughter]

Gary Jordan: Okay. Yeah. Maybe 2022 might be a million now, but okay. I was, I was pretty close. All right, good. Thank you for checking that.

William Harris: Absolutely. Absolutely. Well, I wanted to go to Michael; Michael, you are a storyteller, you know, as a filmmaker and my gosh, you make it look so easy with the final product. And it was fascinating today to see kind of how you break it down and how you take information and try to find a way to make it engaging, uh, to the public. And that really is your job, you know, to do in your challenge, but were you always interested in space and space exploration? Um, how was it that you came to collaborate with, with Goddard in this way?

Michael Starobin: Well, you know, I’ll, I’ll say it’s the same story I think for all of us. I also, uh, thought when I was very young, at four years old, I was watching the Apollo 17 launch from the living room of my grandmother’s, uh, house and said, oh, I’m going to be an astronaut. And, uh, I, we, I am not a scientist, I am not a mathematician, and those dreams die hard. And then you realize what I am is something different. I’m a creative, I’m an artist. And you realize that there might be a way to put these two interests together and to have a value in the space agency. And I, I, I came in kind of through the back door. I had really built a science bureau for a news organization, um, that is no longer, it was absorbed by other companies, but I was working on their national science desk as a reporter. But what I was interested in and started spending more time is developing more feature stories that told about science, about engineering, about changes in the internet when I was a, a younger reporter. And I had spent a lot of my time in school as in the performing arts. And I thought there’s something here that’s just not gelling. I, I’m keeping these spaces separate and I, I want to put them together. And NASA had an unusual position open for a producer to talk about, uh, stories in a new way. And I signed on to the job and thought, well, we’ll see how this goes. And, uh, when I realized that there was a hunger for translation, not just for explanation, I discovered sky’s the limit, if you’ll pardon the pun. And, uh, there was so much flexibility in taking these esoteric subjects and finding ways to make them compelling. And I, I realized we understand the rules of storytelling because it’s the oldest thing we do. We tell stories around the campfire, going back into pre-history. And as recently as today, we tell stories to each other: how was your day today? What, how do you feel, what are you doing later this afternoon? These are all stories. And you have to tell your friends or your family the salient parts or their eyes are going to roll back in their head. You have to find the parts that are interesting and that keep the momentum going. And that’s true, even when talking about rigorous data, rigorous science, what are the parts that matter most?

William Harris: Well, I wanted to, to pivot a little bit specifically to James Webb Space Telescope, because what an exciting project to represent. Um, and you, and, and really the material is so fantastic to help the public understand it. Um, and I think it’s a big challenge we face in general in, uh, space interpretation centers like ours at Space Center Houston, where we have these objects that do amazing things, but when people see them, they’re static. And there’s a real, you know, question about, that brought someone to the Moon? Or, that actually was a suit that an astronaut wore in order to go and do a, an EVA (extravehicular activity)? So my question to you is, if there was such expectation around James Webb, and then of course there were challenges which can happen, it got delayed and delayed and delayed and delayed. And so, you had to maintain the excitement, um, through different visual representation. So, uh, did you anticipate that in your planning that you were going to have to keep refreshing and coming up with new ways to interpret, to sustain the public interest and enthusiasm is, and then the corollary to that is, um, you know, the cost was going up and there were a lot of questions about, should we just cut our losses and not send this into space, um, is it really worth the investment, are we going to get, uh, insights, scientific insights from it that are really going to advance humanity and, and our understanding of, um, not only our solar system but the universe?

Michael Starobin: And William that’s, that’s a superb pair of questions. And I, you’re absolutely right That we were conscious all the time of how do we maintain audience interest in the mission. But, you know, it had this inherently built-in drama to it. So the fact that it kept getting kicked down the road, on one hand, kept making audiences, we would see and then responses we would get from the public of, ah, when are you going to launch this overpriced behemoth, to a ratcheting up of tension and drama. So if you lean into the drama and you leave the, the hard engineering realities to the engineers, we focused on, fine, there’s a lot more stories we can tell: how is it going to work, why was it designed this way, what are the challenges, why are these things harder to do than you thought? There’s so many stories for Webb to tell. We focused on that. And to tell you the truth, it gave us a chance to really stretch out with some ambitious plans that a, a faster tempo might not have allowed us to do, but that was definitely making lemonade out of lemons. In terms of the question about cost, I think it’s important to say that, you know, filmmaking is expensive but there’s nothing like spaceflight to really make you take a deep breath about budgets. We knew that the agency itself is going to face certain political challenges, of course: this is public money to do something that most people would question its ultimate utility. But I, I think to myself, whenever I speak about, is it worth the cost, you know, what is the value of a symphony or a painting? Well, it’s priceless. There’s no value at all, but I’d hate to live in a world without them. And I feel that way about Webb and other instruments and other missions. Is it worth it? I suppose if you’re looking for return on investment, the return is that all of us become greater than the sum of our parts. We expand, not just what we know, but what we’re capable of dreaming about. And we can focus that on rigorous fact, we can focus it on actual observations. We can focus it on our trust in each other to be telling the truth about what our machines do, our process and our data. And as a storyteller I think, what an opportunity to find something dramatic in something that’s fact-based and yet full of mystery and discovery. So, is it worth the cost? My feeling is its essential cost. It’s, it’s vital for a vibrant society to do.

William Harris:I totally agree. [Laughter]

Michael Starobin: And I thought you might be biased on this one.

William Harris: A little biased, but I think that’s, I think a challenge in society now, because we become very literal and we also have very low tolerance for risk. And uh, you know, the, some of the greatest discoveries were accidents, things that were not the intent, um, or the question that, the main question that had been asked, and that as a consequence of it, we had other tremendous insights and understandings. And we all know that, uh, we on Earth are the greatest beneficiaries of exploration and science as we’ve been understanding our Earth’s needs, challenges and issues that we’re facing. Um, Thalia, I think you probably have the most challenging job in trying to, uh, help people understand exoplanets, because we know they’re out there, we do know they, they exist, and we are collecting data in different ways. Um, and I’m sure that the data we we’re anticipating getting back from James Webb is going to help, right, in that understanding, um, and providing us kind of with, with, with more data. But, uh, how do you respond to the public or people who say to you, why are you focusing on those things, they’re so far away? Why is that relevant to us here on Earth?

Thalia Khan: That is a great question. Um, and that’s actually one of my favorite questions to answer when people ask me, like, will we ever be able to visit an exoplanet? And I tell them, no, we won’t because they’re too far. Um, and then they ask, well then why do we study them? Why do we care about them? Um, and there is a number of reasons why we want to learn more about planets outside of our solar system. Um, you know, because it really, studying exoplanets tells us a lot about our own planet. It tells us a lot about the own, our planets and our own solar system. Um, you know, it can really provide a lot of insight into, um, whether or not we’re alone in the universe or how we got here, um, and how the universe works. And by better understanding those planets outside of our solar system, some that are, but a lot older than Earth, some that are a lot older than our solar system, um, can really help us identify, um, our place in the universe and maybe what the future holds for us. So, um, it’s a very interesting, uh, topic to dive into. Um, and you know, I think it is very important to learn about, you know, where we come from and um, our place in the universe and being able to, um, you know, use telescopes like the James Webb Space Telescope to tell us a bit more about those other planets will definitely advance our knowledge in that area.

William Harris: Well, you know, it is, it is fascinating challenge. And I think we live in a time when people again, are very literal. Um, I had the good fortune, my grandfather lived to 106 and um, got to know him as a young adult, and he was born in the late 1800s. And it was amazing in a hundred years of his life, all that he saw, the advent of: you know, having plumbing in your home, electricity, um, the advent of the car as a common transport vehicle for individuals, because he used to ride a horse, you know, early in his life. Um, that when he traveled to Europe, he went on a steamship. Um, you know, so all these technologies that have, we’ve developed in just a hundred year’s times really remarkable. So what, who knows what the next a hundred years will hold and, and what these discoveries and insights are going to provide for us. And you know, there’s a lot of research happening around new propulsion systems, which can get us there hopefully a lot faster and that’s going to completely change, uh, our approach to space. And then also space tourism. You know, we now have ways for everyday citizens to go into space, and soon, as Gary was describing with the Axiom project with NASA, they’re going to be private citizens going to do research for a week on a space station. Um, and then there are three proposed space stations, you know, in the next decade. So it’s, times are changing very rapidly. And, and uh, so how do you keep on top of these rapid, uh, introduction of new content, new information, new perspective, new ways of, of looking at things? Um, how do you keep yourself informed in determining how to communicate those evolving, uh, strategies and architectures? Maybe begin with you, Kaitlyn.

Kaitlyn Soares: Sure. Um, so I think, um, across the agency we do a pretty good job at communicating with each other. Um, NASA has, uh, don’t quote me on this, I believe ten different centers. Um, and we all work together as a, as a larger communications team throughout the entire agency. We coordinate a lot on best practices, we have a community of practice. Um, you know, there are a lot of resources that the agency offers us to be able to, um, keep up to date with what the best communication strategies are at any given time, um, as you know, professionals in, in the field ourselves, uh, these are things that we’re constantly reading about and, um, research searching through what other agencies or other brands might be doing. Um, there’s very much a marketing, um, uh, relation to what we do and, uh, staying up to date with the best practices is, um, more or less the best practice. Uh, so, so we do that. Um, I mentioned data sonification, um, this is something that NASA, um, has done in the past but is doing more of now. Um, so we work with, uh, musicians and, and folks who are, um, you know, masters in the field of music to, to learn more about how we can sonify data. Um, so really it, it, it depends on, um, uh, clear and, um, consistent communication between, uh, the centers and fellow communicators, um, like my friends here at Goddard, um, and also, um, folks in, in, in different fields. Bringing in guest speakers, learning more about what they’re working on, um, sharing our, our experiences in different fields.

William Harris: And Gary, how about you, my gosh, you are charged with, in very short order, being able to present new concepts and ideas and, and insights and things that are happening. And we know the people delivering that are really busy doing their jobs, and sometimes they’re not as accessible as you want them to give you that latest information. Uh, so how do you balance that? How do you manage that?

Gary Jordan: Well, um, I’ll just, I’ll piggyback on what Kaitlyn was saying and, and stress how important relationships are. Um, it’s certainly one of the, one of the keys to, to having successful communication. Um, you asked about how we can stay on top of the latest, how, how do we effectively communicate; building relationships across the board has been, I, I think one of the strengths to doing a good job of that. Um, it, it is, it is getting to know people. It is, um, having them trust you, and that’s internally and externally. Um, particularly with this Axiom project, it is very important to create strong relationships with Axiom Space, with SpaceX, and with people inside of NASA who all are communicating with each other so we can all be on the same page and execute the same mission, and we’re not talking in the void or working in the void. And it’s certainly been challenging, but I think what’s very unique and great about that particular project and, and trying to execute it is that it’s not necessarily starting from scratch. It’s certainly a new approach to human spaceflight, um, especially for, for NASA. We are, we are in pretty much brand-new territory here. But it’s, it’s, we can lean on experiences like Commercial Crew and the relationships we build with commercial companies. Of course, we have commercial companies that deliver cargo to the space station. Uh, we have the International Space Station U.S. Laboratory, that’s working with companies all around the globe, U.S., especially, uh, contributing science investigations to the space station. And we’re, of course, working with all of them and, and getting to know context. And I, and I have, you know, I get to know all these great people, these smart people, and it is fantastic. But to be a successful communicator, not only externally, right, to make sure that the public and your intended audience is, is getting the messaging, um, it, that’s not only a very strong skill that you should have as a communicator but, and this is not necessarily being in this job, being a strong communicator, this is literally anything that you could do, uh, whether you’re a scientist, engineer or anything contributing to the space industry, uh, is to work on those communication skills and relationship-building.

William Harris: So Thalia, I wanted to ask a similar question of you, but with a slightly different twist, because for many years there really were kind of two nations who were real leads in space exploration, the former Soviet Union and now Russia, and the United States. And now you have scores of country around the world who are exploring, and now there are nations who are very interested and going deeper into our solar system and have done that successfully, and are also looking, uh, further out of our solar system and, and beyond. Do you report on, represent in any way, or acknowledge, what other nations are doing when you’re talking about NASA’s research around exoplanets and deep space?

Thalia Khan: So I think, uh, exoplanets is pretty universal in terms of, you know, the discovery and characterization. We have a lot of partners that we work with, um, you know, from other agencies. And I think the collaboration of, um, you know, a lot of different minds, a lot of brilliant minds around the world, uh, definitely does contribute to advancing the science of exoplanet exploration. Um, so I think it’s definitely essential for, um, you know, our scientists to be able to collaborate. You know, they oftentimes get to go to conferences, although they’re virtual now, but they did get to go in person, um, you know, where they get to talk to their colleagues, you know, from different agencies, from different, um, you know, countries. And being able to have, have that collaboration and being able to, um, you know, coordinate on, you know, the, the discovery or collaborate on a paper is super-important to advancing the science. So it’s definitely a core part of, you know, making sure that science is accessible and making sure that that science is, um, you know, being, um, you know, reviewed and is being, um, shared.

William Harris: So, Michael, I wanted to ask a slightly different question of you, and that is around, because you have such an important medium, we’re visual beasts, humans, right — or I shouldn’t call us “beasts” — but we’re visual species, and we love things that help us understand our universe, primarily visually. And so, um, and film is so important, important part of human expression and documentation and interpretation. Um, are, do you have a, a project that you can share with us that’s kind of on the drawing board that’s coming up that space-related, uh, that we can look out for?

Michael Starobin: I’ll give you a, advanced notice about something that’s coming in another 18 months, and that’s the return of the OSIRIS-REx (Origins, Spectral Interpretation, Resource Identification, Security-Regolith Explorer) mission to Earth. Uh, I was the director of live coverage when the OSIRIS-REx probe made contact with its asteroid called Bennu, uh, last October, now about 16 months ago, it was a really exciting operation. Uh, we’re operating a probe out in the asteroid, uh, belt, um, actually adjacent to the asteroid belt, making a sample and bringing it back to Earth. And it’s going to be landing in the Utah desert in 2023. And this is something that’s still, uh, a little further off than I think people imagine, we don’t usually plan our lives that far in advance, unless you’re looking at, you know, going to school for a number of years. Uh, but it’s really something we’re starting to pay attention to because it’s an incredibly exciting story, bringing back an extraterrestrial sample to Earth. Um, and it, visually speaking, it’s very complicated to tell well: there’s a high-speed object coming into Earth’s atmosphere that we’re tracking, and we’re going to monitor as it lands in a designated landing zone via a parachute, uh, and crews going to retrieve it very carefully, and it’s going to be remote so how do you get those pictures back in real time, and how do you illustrate the journey hundreds of millions of miles of this probe going out and coming back? So the data visualizations, and the conceptual animations, are all very sophisticated to tell well. This one is, uh, really on my mind. I’m, I’m excited, I’ve been following OSIRIS-REx since I made the original funding film for it back in the first few years of the, the 21st century. And now to see that it’s coming back to Earth, and being part of that team to tell its, uh, its other side of the story, I’m very excited about. Uh, so watch for that, uh, in a year and a half.

William Harris: I’m very excited about that as well. We actually broadcast the recording of the encounter with the asteroid and the, the crash and, and people were absolutely fascinated by it. So I am really curious to see what that sample can tell us once it returns to Earth next year. So, fingers crossed, it all comes back and everything goes well with the reentry and the, the land and the desert. I am sad to say, we’ve come to the close of our time. It is absolutely been fascinating speaking with the four of you and I’m sure we could go on for much longer, but I wanted to express my heartfelt thanks on behalf of Space Center Houston for sharing your experiences, insights, views, and, and stories. It’s, it’s absolutely been intriguing and I’m sure our viewers are, are enjoying it very, very much. And so just again, want to thank all of our viewers for, for being part of this fascinating conversation. And if you’d like to learn more information on this topic, please follow Space Center Houston on our social media channels and check out our blog at spacecenter.org. Again, my heartfelt thanks for our panelists. And we look forward to seeing you again at another Thought Leaders program at Space Center Houston.

[Music]

Host: Hey, thanks for sticking around! Really good conversation I had with some incredibly smart and talented folks. I, uh, I hope you learned something today. Really do. Um, if you like this podcast, we have a lot of episodes that you can check out and there’s also a couple of other podcasts across the agency; go to NASA.gov/podcasts to check them all out. If you want to talk to just us, we’re on the NASA Johnson Space Center pages of Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. Just use the hashtag #AskNASA on your favorite platform to submit an idea for the show. Make sure to mention it’s for us at Houston We Have a Podcast. This panel was recorded on January 21, 2022. Thanks to Alex Perryman, Pat Ryan, Heidi Lavelle, and Belinda Pulido for their work on the podcast as always, and thanks to Kimberly Lobit, Michael Hare, and Meridyth Moore from Space Center Houston for putting this together and sharing this discussion for the podcast. And thanks of course to William Harris for moderating the discussion, and to Michael Starobin, Kaitlyn Soares and Thalia Khan for a great conversation. Give us a rating and feedback on whatever platform you’re listening to us on and tell us what you think of our podcast. We’ll be back next week.