Flying unique, one-of-a-kind aircraft is one of the specialties of NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California. A process, built on the foundation of the earliest experimental aircraft, promotes flight safety, and reduces risks associated with even the most interesting concepts.

Examples include the X-29 with its forward-swept wings, the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy 747’s garage door-like mechanism on its fuselage, and the subscale Preliminary Research Aerodynamic Design to Lower Drag, or Prandtl-D, flying wing.

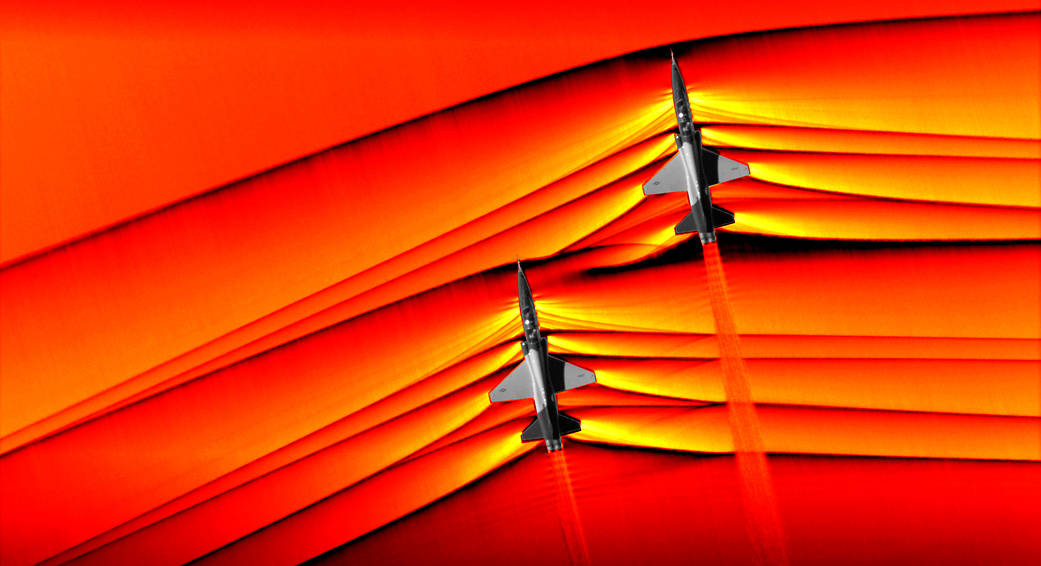

That legacy will expand, with development of the battery-powered X-57 and the uniquely shaped, quiet supersonic X-59.

“We make some pretty strange looking things fly,” said CJ Bixby, NASA Armstrong chief engineer and technical advisor to the center director.“

Whether the aircraft is new and experimental or established and retrofitted for a new task, safety is paramount. The responsibility for airworthiness falls on Bixby and Bradford Neal, NASA Armstrong senior technical adviser to the center director. Neal also serves as the chairman for the airworthiness and flight safety review board and chair for the X-59 aircraft.

“Airworthiness is being ready to fly,” Bixby said. “That means the airplane is a known configuration, everything that you need to fly works, and that the people who work on the airplane are trained and have procedures to follow.”

Another key is nothing flies without the paperwork.

“You can have an airplane sit on the ground and know it’s a perfectly good airplane, but if you don’t have all the pedigree and the paperwork, you’re not airworthy,” Bixby said.

The airworthiness process includes an independent review of what tests the project is attempting to perform and whether they have everything they need – correct procedures, data, thorough risk mitigation, and contingency plans – to do the work safely.

“I work with the projects to help them get through that process,” Bixby said. “That’s my main focus.”

The process begins when a project presents its flight test plans to a Flight Readiness Review Board, an ad hoc board of experts with project-relevant knowledge. The board does a deep dive into the plans, Bixby said.

Next is a review by the Airworthiness and Flight Safety Review Board, a board composed of senior center leaders. It looks at test objectives, how the tests will be conducted, potential risks, and risk mitigation. Then the Project Team has a tech brief.

“The project says here’s the test objectives, here’s how we are going to do it, and here’s all the items we closed out from the last review,” Bixby said. “If the board finds that acceptable, the board signs the flight request. Ultimately the request goes to the center director for approval.”

In flight research, it is not possible to mitigate all risk. The question is how much risk is acceptable – a judgment call based on experience.

“When you look at any of our flight safety review boards, there are a couple hundred years’ worth of flight test experience sitting around the table,” Neal said. “In many cases you have run across something similar before, and so you can start to gauge the risk that remains.”

For the X-59, being built at Lockheed Martin Skunk Works in Palmdale, California, the airworthiness process is the same, Neal said.

“The scale of the process is tailorable,” Neal said. “For X-59 it’s more involved, so we have a larger team of subject matter experts doing the independent review. The airworthiness and flight safety review board has a couple of extra folks on it because we are interfacing with other centers who have done work. It’s the same set of briefings, but the scope changes.”

The X-59 aircraft is a bold, new design, engineered to reduce the sound of the sonic boom that occurs during supersonic flight to a quiet sonic “thump”. Many of its components, however, are from well-established aircraft. Landing gear from an Air Force F-16 fighter, a cockpit canopy from a NASA T-38 trainer, and a control stick from an F-117 stealth fighter, are among the repurposed parts.

The airworthiness process – documents, maintenance procedures – are being created as the Quesst mission progresses. Additional testing and inspections can help fill knowledge gaps.

NASA headquarters adds another layer of review in auditing the center’s airworthiness processes.

“We do have other organizations that come in and look at us and say ‘okay, your process is sound and if you execute that process as you have laid it out you will have a high probability of being safe and getting the data,” Neal said.