Part 5 in Kennedy Space Center’s History series

In the 1990s, the number of space shuttle missions doubled that of the ’80s, enabling everyday wonder, rather than rare scientific study.

The shuttle program was in full-swing and proved to be Earth’s bridge to space, serving the U.S., Russia and our other international partners.

Throughout the ’90s, the agency enhanced our knowledge of the world around us through the first three of four Great Observatories, proved that humans could handle long-duration spaceflight through the Shuttle-Mir Program, began to assemble the International Space Station and launched additional planetary missions, allowing us to explore further.

“During the mid-shuttle program, we had a well-oiled machine with a clearly defined mission, and it was our job to keep it flying safely,” said Jay Honeycutt, Kennedy’s center director from January 1995 to March 1997. “When people look back at that time, I hope they see an era of high performance in a challenging environment, safely executed by a motivated workforce who really enjoyed doing what they were doing.”

NASA’s first Great Observatory, the Hubble Space Telescope, was processed at Kennedy and launched April 24, 1990, aboard shuttle Discovery. Hubble has been attributed with expanding our understanding of star birth and death, and has transitioned black holes from scientific theory to fact. Since Hubble launched, it has gone through numerous maintenance and servicing missions, including the replacement of its optic lens.

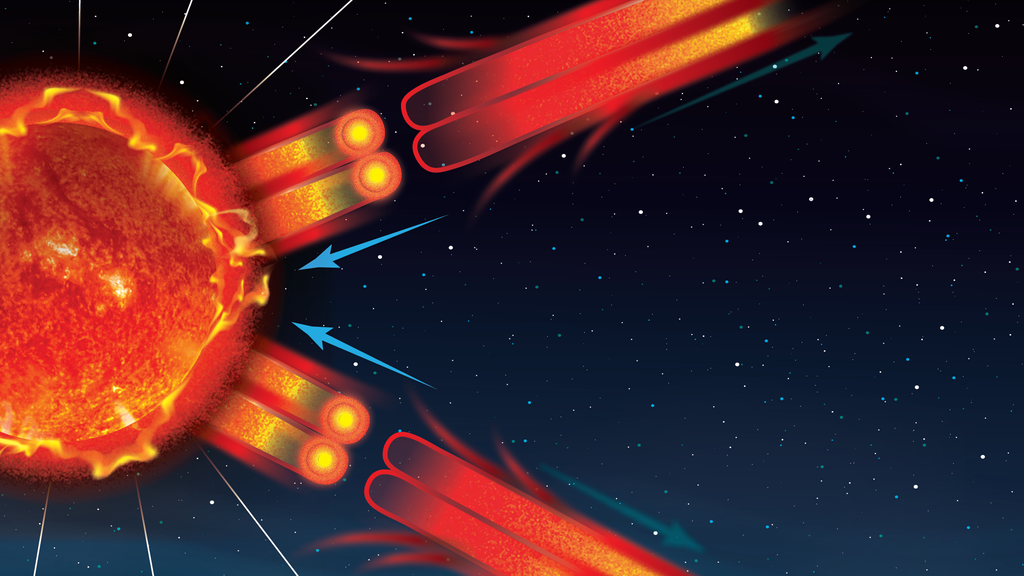

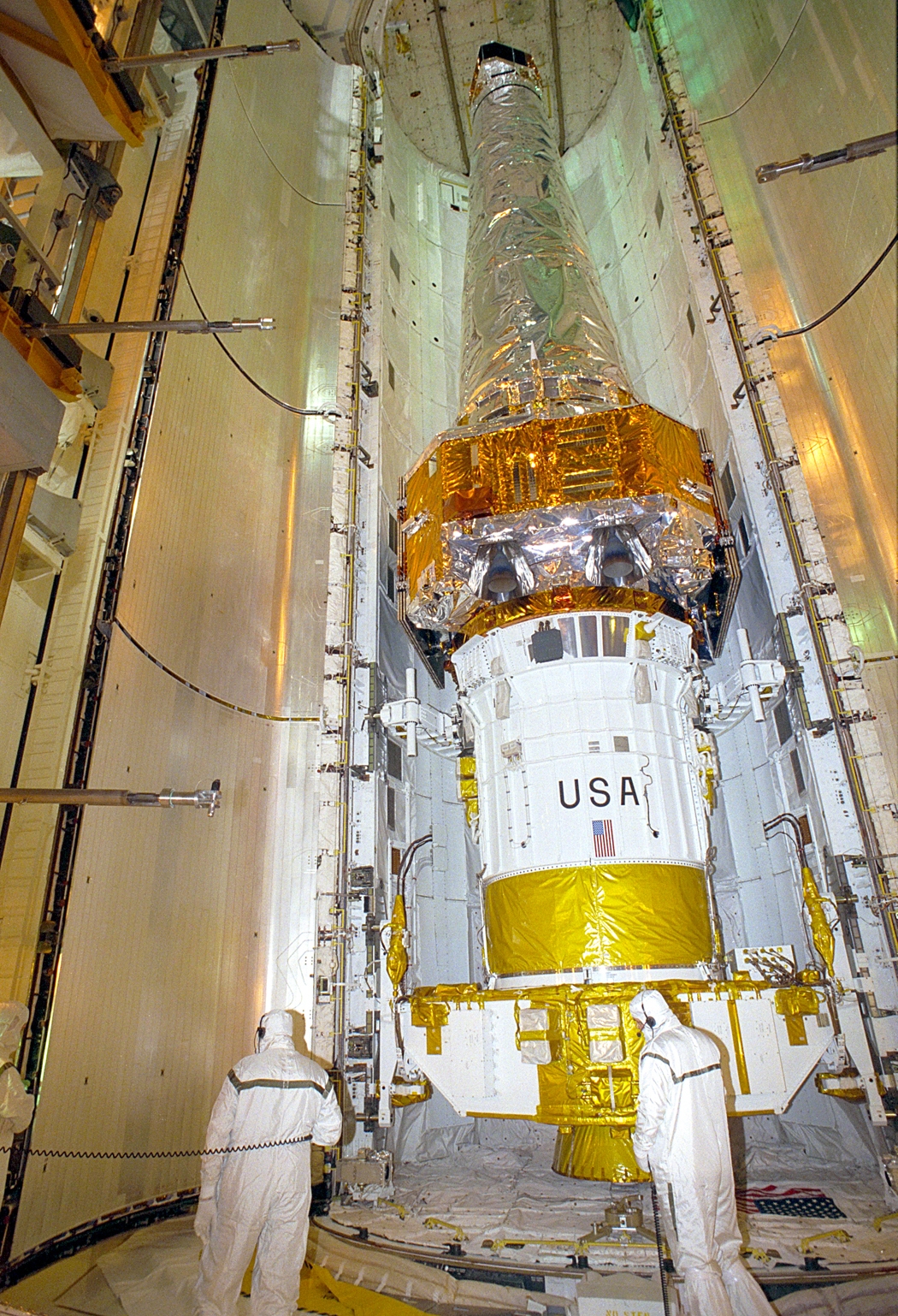

The Compton Gamma Ray Observatory, a 17-ton satellite, was the heaviest payload to have flown in space at the time of its launch April 5, 1991, aboard shuttle Atlantis. This mission collected data on high-radiation sources called gamma rays, characterized by their extremely high energies.

The third was the Chandra X-ray Observatory, launched into a high Earth orbit aboard shuttle Columbia on July 23, 1999. Chandra was designed to study black holes, supernovas and dark matter in greater detail than previously possible to increase our understanding of the origin, evolution and destiny of the universe.

It wasn’t until the ’90s that the space shuttle was used for the primary mission for which it was designed, the assembly and outfitting of a space station.

The construction of Kennedy’s Space Station Processing Facility, or SSPF, began in April 1991. One of the special attributes of the facility was the ability to perform multi-element integrated testing, saving the agency billions of dollars that would have been spent transporting hardware.

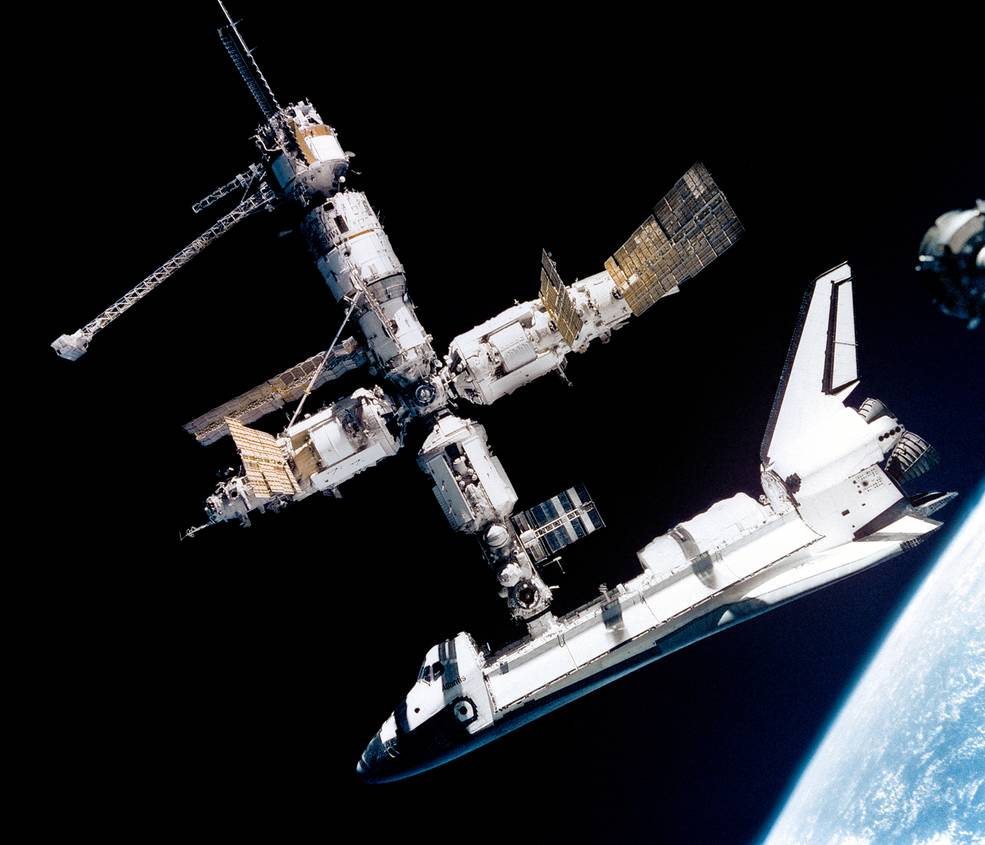

On June 17, 1992, U.S. President George H.W. Bush and Russian President Boris Yeltsin signed an agreement allowing the U.S. to use the Russian space station, Mir, to enhance our knowledge of long-duration missions. The agreement, which became known as the Shuttle-Mir Program, was later expanded to include 10 shuttle flights to Mir with extended stays on the station by U.S. astronauts.

In fall 1994, the Russian-built Mir-2 Docking Module was the first flight hardware to be processed through the SSPF.

During the three-year program, the shuttle docked with Mir nine times. It was a good precursor to the assembly of the International Space Station because it introduced NASA astronauts to living and working in space on long-duration missions.

The first U.S.-built piece of hardware to be processed through the facility was the Unity module in June 1997. Since then, all payloads sent to the station aboard the space shuttle were processed in the SSPF.

By the end of the ’90s, a Russian Proton rocket and two shuttle missions assembled the core of the space station and outfitted it with necessary supplies. The first station assembly mission began Nov. 20, 1998, with the launch of the Zarya control module atop a Russian rocket. Zarya provided the station battery power and fuel storage. The launch of shuttle Endeavour followed Dec. 4 to deliver the Unity node. The STS-88 crew captured Zarya and mated it with Unity, and the new station emerged.

Shuttle Discovery launched May 27, 1999, with the STS-96 crew to deliver and outfit the fledgling station with the logistics and supplies necessary to give the international research laboratory a strong beginning.

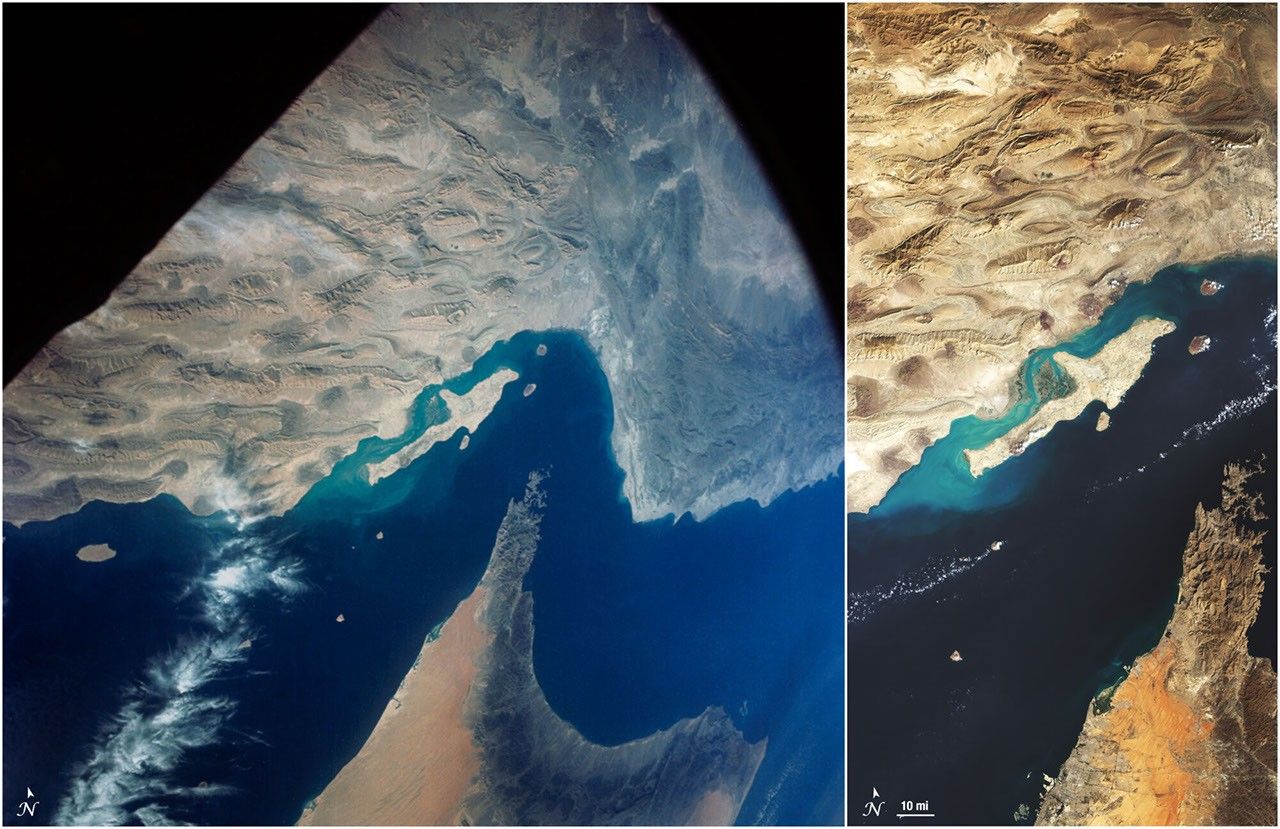

Although the Space Shuttle Program and the International Space Station were the primary focus of human spaceflight at Kennedy, two important planetary missions were launched on expendable launch vehicles from neighboring Cape Canaveral Air Force Station. The Mars Pathfinder with the Sojourner micro-rover launched Dec. 2, 1996, arriving on the Martian surface July 4, 1997. Sojourner, the first rover to explore the surface of the Red Planet, lasted 12 times its life expectancy of seven days and returned 550 images of the surrounding area.

Cassini, a joint venture between NASA, the European Space Agency, or ESA, and the Italian Space Agency, advanced our knowledge of Saturn, its rings, moons and magnetic environment. Cassini launched Oct. 15, 1997, on a seven-year journey to the ringed planet. One of the primary targets was Titan, Saturn’s largest moon. A probe provided by ESA descended to Titan’s surface to directly sample the atmosphere and provide the first view of its surface.

The Launch Services Program, originally known as Unmanned Launch Operations and then Expendable Launch Vehicle Operations, became an official program at Kennedy in October 1998. The program took the separate and distinct work of three NASA centers and combined it under one cohesive organization that serves the agency by procuring, managing and launching awe-inspiring scientific missions.

The ’90s were a very dynamic time at Kennedy. Three center directors saw Kennedy through numerous programs of national and international importance. Though the Kennedy team had a variety of missions and focuses, one theme was constant: Each of the center directors proudly proclaim that Kennedy had and still has the best team around.

“Despite the challenging environment, the Kennedy team delivered excellent results,” said Roy Bridges, center director from March 1997 to August 2003. “We successfully built the ISS, prepared and launched the shuttle on many amazing missions, had an excellent track record with ELV launches, and ramped up our concept of spaceport and range technology development.”