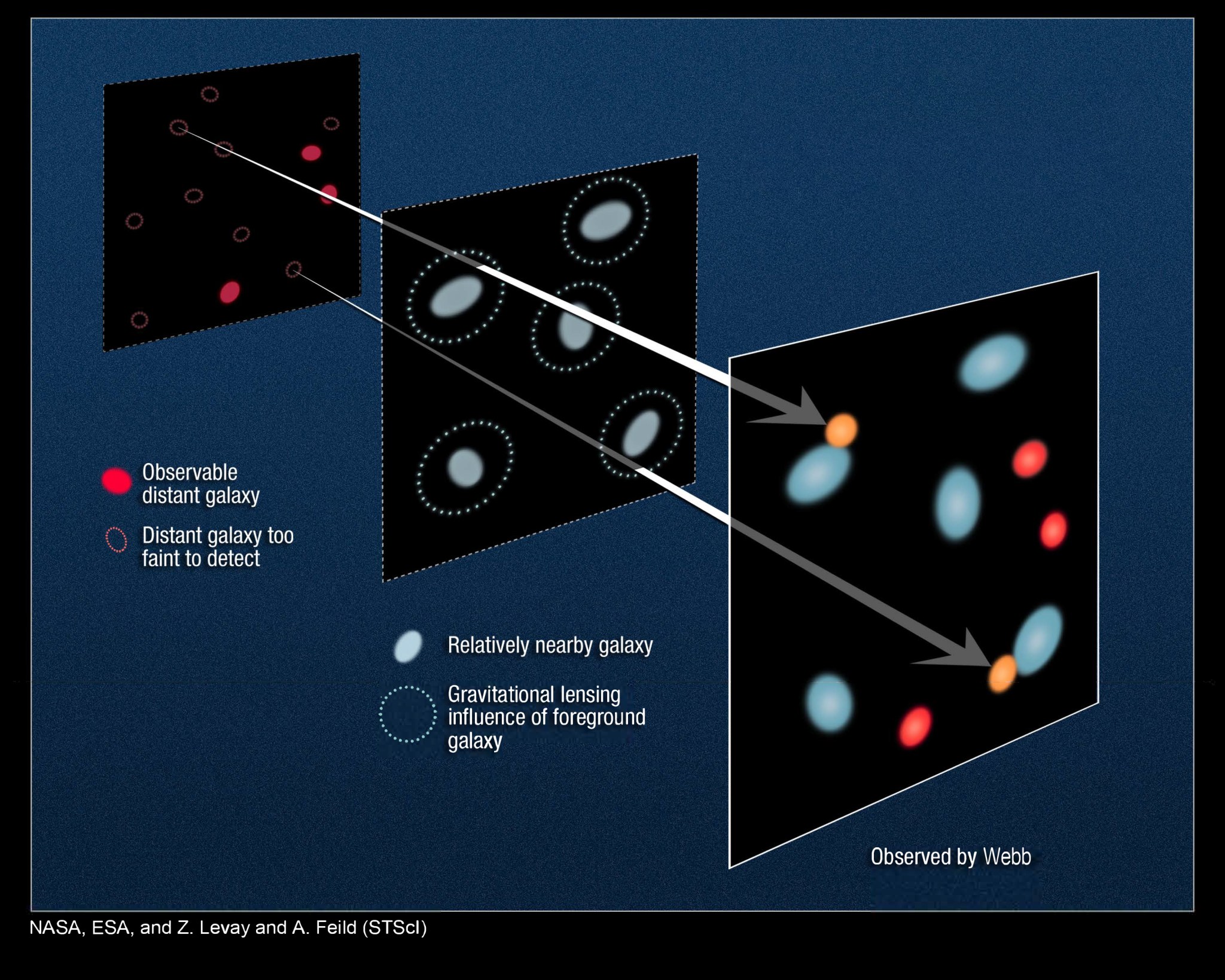

Through the combined power of NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope and gravity creating “natural telescopes” in space, astronomers hope to answer two science questions that are fundamental to understanding the origins and evolution of the universe:

– How did the first galaxies in the universe form, and did they make the universe transparent to light?

– How did later galaxies produce and disperse into the universe the heavier elements that are the building blocks of stars, planets, and even humans?

These questions will be addressed in some of the first observations made by the Webb telescope, slated to launch in March 2021. These observations will be part of the Director’s Discretionary-Early Release Science program, which provides time to selected projects early in the telescope’s mission. This program allows the astronomical community to quickly learn how best to use Webb’s capabilities, while also yielding robust science.

An international team led by Tommaso Treu of the University of California, Los Angeles, has been investigating how Webb can tackle these two key questions about the universe in the Early Release Science program.

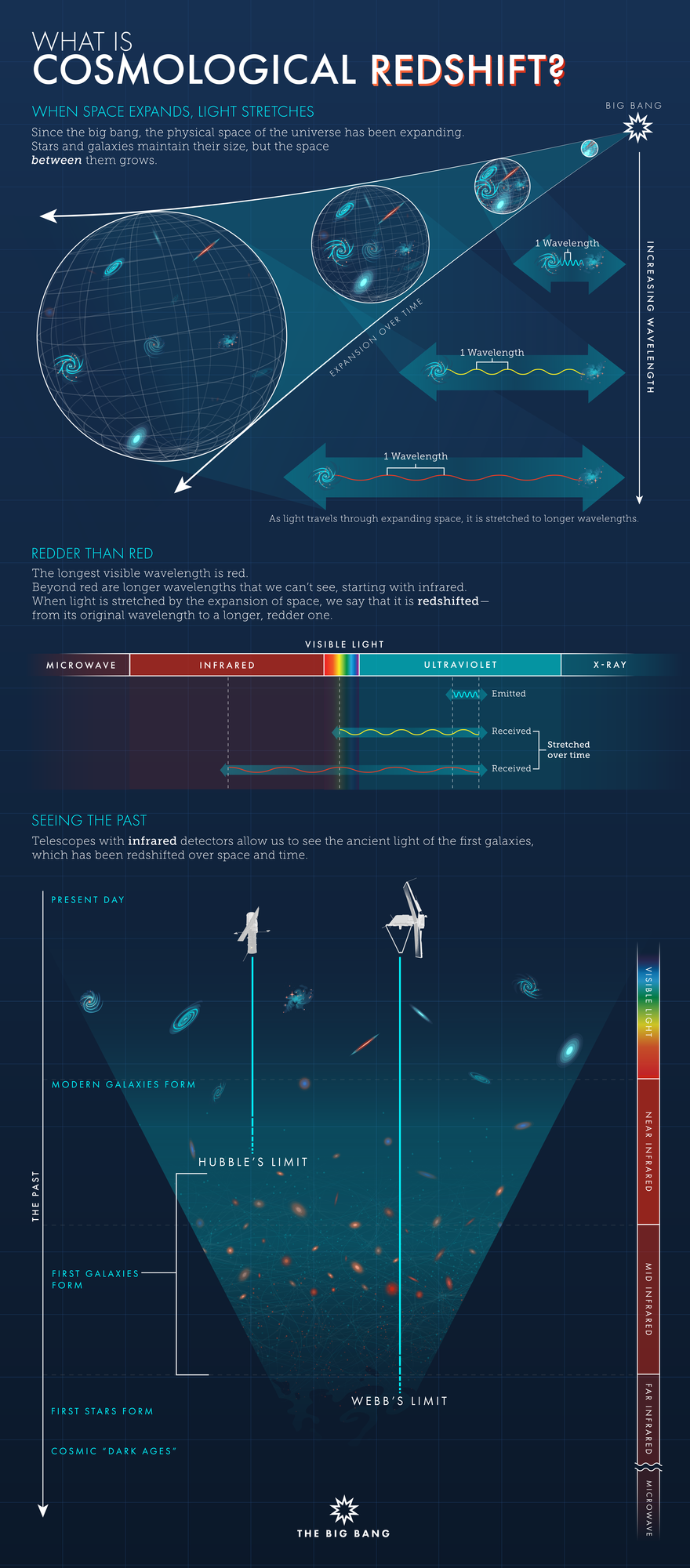

Treu and his team will study the earliest, most distant galaxies to investigate their origins. After the big bang, the universe cooled down. As it cooled, protons and electrons combined to form neutral hydrogen atoms, until the universe became filled with hydrogen and opaque to light. Then at some point, the first galaxies formed, and scientists think these first galaxies emitted enough ultraviolet light to destroy the neutral hydrogen atoms and make the universe transparent to light. This is called the end of the “dark ages.”

“We’re not exactly sure when this happens, and we think it’s galaxies making the universe transparent, but we are not totally sure,” Treu said. “One of the things our proposal will try to do is establish whether indeed galaxies are the ones that are making the universe transparent — ending the cosmic dark ages — and what kind of galaxies they are, what are their properties, and when this happens.”

Using Gravity as a “Natural Telescope“

To see the faintest, farthest galaxies, the team will combine the power of Webb with the magnification of a “natural telescope” in space. The phenomenon, called gravitational lensing, occurs when a huge amount of matter, such as a cluster of galaxies, creates a gravitational field that distorts and magnifies the light from distant galaxies that are behind it, but in the same line of sight. The effect allows researchers to study the details of early galaxies too far away to be seen with current technology and telescopes.

One gravitational lens is Abell 2744, an enormous cluster of four smaller galaxy clusters. Also known as Pandora’s Cluster, this giant collection of galaxies has been well studied, including by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope. Abell 2744 is one of many clusters that scientists can use in combination with Webb to peer back into the universe’s distant past.

“It’s a cluster that we know very well,” Treu said. “The fact that we know it so well means that we can calculate very precisely the properties of the lens. Using our models, we can compute very accurately how the background images have been distorted. Then we can invert that to figure out the intrinsic properties of the objects as they would look without the lens in front.”

Simultaneously, the team will take deep images in the near and medium infrared of two fields offset from the cluster. “We will use those to count galaxies in the very early universe and figure out how many there are,” explained Treu. “Those are the sources that are suspected to eventually produce the ionizing photons that end the dark ages.”

Forming the Universe‘s Heavier Elements

The big bang only formed hydrogen, helium, and traces of other light elements. Heavier elements like iron, oxygen, and carbon, which are made in stars, eventually ended up in the universe—but scientists don’t know exactly how this process happened.

“In astronomy, we think of hydrogen and helium as the light elements, and everything else we call a ‘metal,’” explained team member Alaina Henry of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland. “We want to measure the metals that are produced by the first stars in the first supernovae. This tells us how the stars evolve, and how many end their lives as supernovae, where the heaviest elements—such as iron—are made.”

Identifying the “Fingerprints“ of Elements in the Light

Answering both questions requires the unique spectroscopic capabilities of the Webb telescope. Spectroscopy separates an object’s light into its component colors, allowing scientists to see the “fingerprints” of different elements. By analyzing these spectral fingerprints, astronomers can determine the physical properties of that object, including its temperature, mass, luminosity, and composition.

Treu and his team will use two different spectrographs on Webb, each with different strengths and functions. Comparing and contrasting these capabilities is an important technical goal of their program.

Webb’s Near Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph (NIRISS) gives observers spatial information, so they can determine how a spectrum changes across the sky. However, it has relatively low spectral resolution, meaning it is harder to differentiate between very similar colors.

The telescope’s Near Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) has a quarter of a million tiny microshutters, each as wide as a human hair. These shutters can be opened or closed individually to isolate the light from a particular object. “In exchange for that, you lose spatial information,” said Treu, “but you get much higher spectral information. You can see the motion of the gas, both within galaxies and flowing in and out of them.”

“Webb will effectively be a much more capable spectrograph than we have ever had in space,” Treu added. “It will have multiple instruments to disperse the light. We need to understand the strengths of each one and how they complement each other.”

Expectations

Looking deep into the cosmos, Treu and his team expect to get a very good idea of the opacity of the universe, and also learn how ionizing photons — particles of light —escaped from the very early galaxies. They will also observe nearer galaxies at later times, when the galaxies are forming stars very vigorously.” We will get the best view ever of this process of gas flowing in, forming stars, and then being blown out by super-winds,” Treu said.

“It would be really fun if we found spectral features that we hadn’t seen very often, or maybe not at all before,” added Henry.

The James Webb Space Telescope will be the world’s premier space science observatory when it launches in 2021. Webb will solve mysteries of our solar system, look beyond to distant worlds around other stars, and probe the mysterious structures and origins of our universe and our place in it. Webb is an international project led by NASA with its partners, ESA (European Space Agency) and the Canadian Space Agency.

For more information about Webb, visit: www.nasa.gov/webb

By Ann Jenkins

Space Telescope Science Institute, Baltimore, Md.