An ice shelf collapsed in East Antarctica in March 2022, concerning scientists who track melting glaciers, sea level rise, and other effects of climate change. Catherine Walker, a visiting scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, uses NASA satellite data to look at the progression of events like this one to understand how large ice structures collapse. She is also looking at Jupiter’s moon Europa and what kind of life might be able to survive under the ice there. Learn about her Antarctica adventures and her scientific journey on this episode of Gravity Assist.

Jim Green:On Earth Day, we’re going to talk about water and ice.

Catherine Walker:The ice sheets of the Earth, Greenland and Antarctica are sort of two of the biggest uncertainties, in future climate projections.

Jim Green: Hi, I’m Jim Green, and this Gravity Assist, NASA’s interplanetary talk show. We’re going to explore the inside workings of NASA and meet fascinating people who make space missions happen.

Jim Green: I’m here with Catherine Walker, and she is a management fellow at NASA Headquarters and a visiting scientist at the Goddard Space Flight Center. Catherine has done fantastic research, looking at the oceans and ice on Earth, as well as other planetary bodies. Welcome, Catherine, to Gravity Assist.

Catherine Walker:Thanks. It’s very exciting to be here. (laughs)

Jim Green:Well, you know, I’m really delighted to talk to you about, you know, one of my favorite topics, which is water in whatever form we can get it in. And indeed, you’ve gotten interested in studying oceans and glaciers. How did that happen?

Catherine Walker:Early in my life, we lived near the beach. And so we saw the ocean all the time. And I was sort of just captured by its power, because it, living right on the coast, you get a lot of storm damage and things like that. And other days, you’d look in, it’s flat, calm. And so it was just sort of this dynamic system that you can see moving and doing things on the Earth on really short timescales. And so you know, on a human level, you just want to understand that.

Catherine Walker:Early on in my career, though, I was a geologist. And eventually, that turned into looking at planetary surfaces, things like Mars and the Moon, early in my undergrad career. And then eventually, there was a newspaper article about Cassini had seen Enceladus. And I learned that there were these planets that were made entirely of ice, which, you know, in some, in some sort of thought process that is similar to rock when it’s that far in the solar system. And so I ended up looking at ice on planetary scales, and then coming back down to Earth and saying, “Hey, what does it do here on Earth?” And so I sort of did a roundabout way of becoming a glaciologist.

Jim Green:Well, when you go out in the field, you’ve been actually looking at glaciers. What are you trying to do when you go out and, you know, explore?

Catherine Walker:Yeah, that’s a great question. And I guess there’s multiple answers. The first, first and sort of foremost, when we go out to look at glaciers in my research anyway, we’re looking for how, right at that point where the ocean and ice meet. So these are called marine terminating glaciers. These exist in Greenland, they exist in Alaska, and obviously, Antarctica, which is surrounded by the ocean. And so we look at how the ocean and ice sort of interactions happen over time, and how the warming ocean since that’s the sort of big sink of heat here on Earth, how that changes and how that then affects our ice caps and ice sheets on the Earth. And so we go out there and measure how the ice has, is shrinking, mostly, sometimes growing, but usually using airborne science and satellites. And then some, you know, ground measurements that we go out and measure things like radar, measurements of thickness and things like that. Another answer, though, is we use Earth’s ice sheets to better understand ice on other planets and how it interacts with oceans or water there. And so a lot of the times we go out with the intention of sort of measuring these things, not just for the processes here on Earth, but trying to understand the physics of it so we can sort of take that knowledge and move it to other planets.

Jim Green: Didn’t we just have a big glacial disconnection, where a big ice sheet was broken off? And that and that’s because it just got thinner and thinner and broke off? What do we know about that? And how large was that glacier that broke apart?

Catherine Walker:Yeah, the Conger Ice Shelf, which was in East Antarctica, completely collapsed, which is not totally unprecedented. There have been a few ice shelf collapses in West Antarctica, which is generally thought of as the warmer part of Antarctica. It’s sort of hard to think about Antarctica being warm at all.

Jim Green:(laughs)

Catherine Walker: But the western side is generally what we think about when we think about these melting glaciers and ice sheets that we that we hear about in the news.

Catherine Walker: East Antarctica, on the other hand, scientists generally think of as relatively stable. We sort of have that as our bank of, of freshwater ice on the Earth. It’s very cold, it’s very slow. It’s like the definition of glacial pace over there. Doesn’t really do much. And so we were sort of thinking that it of that place is stable. But yeah, a couple of weeks ago, a small ice shelf called Conger Ice Shelf, which is about 1,200 square kilometers in area. We were watching it over a few months now. But now that we have, now that we know we collapsed, we can use that satellite record to look backwards in time and see what it was doing over time. And we could see that it was just getting thinner and thinner, as the ocean warmed it.

Catherine Walker: And eventually, something called an atmospheric river arrived in Antarctica in early March. And what an atmospheric river is, it’s a big weather event that sort of brings in heat and moisture from the tropics, which is not unprecedented, but very rare in Antarctica, and you get these temperatures and winds and waves that came in with this, with this sort of low pressure event that turned it into this, sort of, “too much to handle” for this thinning ice shelf, so it collapsed.

Jim Green:Wow. Well, what happens to it then? Does it eventually completely get consumed by the ocean that it swims in and then the ocean rises?

Catherine Walker:Yeah, so the ice shelf, as it broke up, it made a few big icebergs that are now floating off into the southern ocean and they’ll go on to melt probably within a few months or a year. You know, sort of trailing freshwater and changing the nutrient amounts for, for ecosystems down there as they go. The other sort of, I guess, concern that we have is now that that ice shelf has come away from the coast, there’s nothing holding back the glaciers behind it. And that’s usually what we worry about when we talk about sea level rise. When these ice shelves around edges of the continent collapse, they can release all this ice uphill, to slide more quickly into the ocean, and that’s what will cause sea level rise.

Jim Green:Wow. Well, how does your research fit into the bigger picture of climate change?

Catherine Walker:Yeah, that’s a great question. So the ice sheets of the Earth, Greenland and Antarctica, are sort of two of the biggest uncertainties, in future climate projections and in particular projections, for sea level rise, timing and volume, I guess. So when we think about how, you know, studying ice and ocean interactions, how those inform on future climate predictions, we usually think about how those will affect sea level as we know it.

Catherine Walker: And one of the biggest unknowns right now anyway, in glacier science is how quickly something can collapse, which seems like a big, fairly easy question to answer, like, you know, if you look at the Cliffs of Dover, for example, why aren’t those collapsing? How are they holding themselves up? You know, it’s not a miracle. That sort of material, rocky material has a strength to it, it can hold itself up to a certain degree, and then you get these little calving off periods.

Catherine Walker:Same thing happens for ice. We just watch things like this recent Conger collapse, Conger Ice Shelf collapse. We use those events to study how strong ice is. And then we can study how quickly these retreats can happen, and how then how quickly sea level rise will happen. So yeah, that’s how those two sort of feed into our expectations for the future.

Jim Green: Well, I heard that you also had a robot in Antarctica. What were you doing down there? And what was that project all about?

Catherine Walker: Yeah. So this is a nice tie-in to this sort of cross between Earth science and planetary science. So when I was a postdoc researcher at Georgia Tech, I was working on a project looking at the ice-ocean interface. So when we think about these ice shelves in Antarctica, it’s just this big slab of ice that’s about, can be up to 100 meters thick. So we’re talking substantial ice cover. So you have this ocean underneath that is completely removed from sunlight, or really any current activity or anything like that.

Catherine Walker: It’s just sort of this cavity underneath ice. And so we were down there, trying to study what’s happening right at that interface between the ocean and the ice underneath, and what sort of life lives under there. And so, you know, how else do you do that, but you send down a submersible vehicle. Unfortunately, people couldn’t go in it, which would have been fun, but we couldn’t go. It was just a little, basically a camera and some oceanographic instruments. And we sent it down. It sort of looked like a torpedo.

Catherine Walker: And we sent it down through a hole in the ice, and it swam around down there. And it was really neat, because I guess as a, as a glaciologist, or an ice person, I was sort of just there to see what the shape of the ice looked like and what how much was melting and things like that. But once we got to the sea floor, we could actually see these, you know, anemones and starfish and like something I thought was a lobster but it was just a giant shrimp. It was it was really cool. And you know, just thinking of how these things live down there with no sunlight. And no, you know, no nutrient source or anything like that was, was sort of super cool to see. Just sort of proved the point of like, you never know what you’re going to find when you go exploring.

Jim Green:That’s right. And you always have to look. So yeah, so these interfaces between the ice and the water are really important. And I’m just delighted that you were continuing to find life in those interfaces, because the Earth is not the only planet that has those kinds of interfaces. But before we talk about things out in the solar system, I want to ask you about some memorable stories that you may have had in the Antarctic.

Catherine Walker:Sure. So one of the most memorable things that happened to me when I was there. So maybe this is, you know, not clear to anyone who hasn’t been there, maybe. And I didn’t know this before I got there. But so GPS doesn’t work near the poles, just because it sort of searches and searches for north or south but can’t find it. So you can’t use that to figure out where you are. And since we had this robot underneath the ice, we also couldn’t visually see it, because it’s covered, you know, there’s ice, but then there’s lots of snow on top of it. So you can’t see through the ice or anything.

Catherine Walker:And so to figure out where the robot was below us, when we were standing on top of the ice, we had these giant magnetic rings that we had to hold and wear earphones. And when the magnetic pinger on the robot was below us, it would make a buzz in our, in our ears. And so we were sort of wandering around this great big area on the ice, hoping to hear a ping to figure out where the robot was. And I saw this sort of hill, and I was like, “Oh, I’m gonna go that way.” And so I started walking up. And I knew from my experience in my PhD that usually those hills meant that this was the transition between sea ice and an ice shelf. It’s just windblown snow, that sort of making that transition. So sea ice is not permanent ice, it’s, it’s frozen out of the ocean in the winter.

Catherine Walker: And so that’s what I had been walking on. And I was like, “I’m gonna go up onto the ice shelf, which is where we thought the robot was underneath.” And so knowing my significant experience looking at satellite images of the area, I said, “Oh, I didn’t realize they were attached to each other, the sea ice and the ice shelf.” But in my eye at the time, I was like, “No, it looks connected, I’m going to walk up this hill.” And so I walked up, and suddenly I dropped up to my armpits, basically, into the snow. And I had to hoist myself out.

Catherine Walker: And I grabbed the, the magnetic ring. I was like, “Oh, my God, what happened?” and I looked back down, to where I popped out of, and there was this giant opening. And it was basically it wasn’t connected, I was right, from my satellite experience. There was about a 20-meter drop down into the ocean from there, and so survived that. (laughs) But that teaches you to trust your intuition and not your visual sight. (laughs)

Jim Green: Wow. Yeah, that could have been dangerous. I’m so glad you survived that, indeed. (laughs)

Jim Green:So as our ice sheets begin to melt, and that’s going to continue to happen. Is there a process for which they can come back?

Catherine Walker: That’s a great question, one that’s sort of goes to our hope for the for the future, right? Because we hear a lot of news reports and things that say, Hey, you know, expect the worst. Another ice sheet or an ice other ice shelf has collapsed? Oh, no. Which it is sad to watch them collapse, of course. And there is a large amount of evidence that the ice on Earth is shrinking, of course, but one of the things that we don’t know, aside from some of the stuff I talked about before about how it’s holding itself together, we also don’t know, you know, as more ice melts into the ocean, we don’t know how all that freshwater getting added to the system will change the ocean currents in the ocean system as well.

Catherine Walker: And so most of what we think about in terms of how If we expect things to change in the in the future is set up based on how things work now. But we don’t exactly know, you know, if you add a whole bunch of, you know, say all of West Antarctica disintegrated, which hopefully it doesn’t. But even if it all did, you know, what would that actually do to the ocean? And it might even stop itself, it might change current systems and things like that to either slow or stop the process from continuing.

Catherine Walker: So we don’t know a lot of those natural feedbacks that might actually kick in to help, you know, reverse the, the process. They’re also, you know, a lot of, I guess geoengineering ideas about how to sort of enhance the albedo of the earth and reflect more sunlight back up. You know, the Earth has a natural process in sea ice formation that does that already. But if we can sort of prop up that process and cool things down maybe, there are a lot of ideas like that circulating as well. So it’s not all it’s not all bad news.

Jim Green:Well, your experience on Earth about oceans and ice, and we’re finding those kinds of objects out in the solar system. What are the top icy moons that you’re interested in when you when you think about these, these wonderful phenomena?

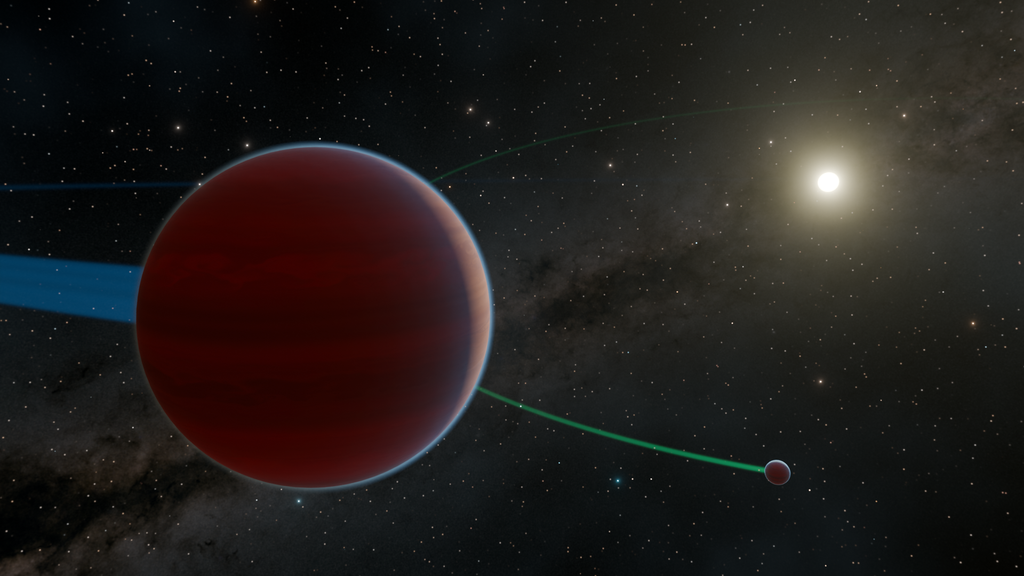

Catherine Walker:Well, the first one that comes to mind, of course, is Europa. It’s sort of this perfect, or seemingly perfect laboratory, for life to maybe evolve if it’s there. It’s got a liquid ocean underneath a nearly pure water ice ice shell. We can see in the cracks on the surface, that there’s a lot of salts and things that you might expect from an ocean very similar to ours. So that one’s sort of a pretty obvious one.

Catherine Walker:There’s also Enceladus which is a moon of Saturn. (laughs) Which also likely has a, well, it at least has a south polar ocean if not a global ocean, also a pure water ice ice shell. And there’s other ones I guess, like, you know, Ganymede or Callisto, which are older well and Ganymede, it’s much larger. But a lot of these places that maybe people don’t think about all the time, but I think it’s hard for us to imagine an ocean below any sort of solid crust, but there’s a lot of these places. a lot of these icy moons out there that, you know, look very solid to us and are expected to be solid because they’re sitting out in the middle of, you know, way-below-freezing solar system, but they actually have a lot of water. And you know, comparatively Earth is pretty dry compared to some of these places. So it’s exciting.

Jim Green: It sounds to me like our new view of the solar system is that the solar system is a soggy place.

Catherine Walker:(laughs) It’s a good way to put it.

Jim Green:(laughs) Well, what projects are you currently working on now?

Catherine Walker:So a few things, I guess, out in the solar system, we’re working on a project to try to look at how life might have evolved in Europa’s ocean, looking at sort of how you might expect things to evolve with the lack of sunlight, which is usually what we think of here on Earth, we think of “oh, you need photosynthesis and sunlight and water to survive.” And obviously, they have enough water on Europa, but none of those other things, and a lot of radiation, which we don’t have here on Earth. And so we have to sort of rethink how we think about how life forms and how it maintains itself. So we’re looking at that.

Catherine Walker:Another project I’m working on is looking at that Conger Ice Shelf that we were talking about earlier, how that is going to affect that particular region of Antarctica, in the near term and long term. And another project that I’m working on now is just looking at sort of how to how to better I guess, observe high mountain regions. The ICESAT spacecraft, it’s a really great spacecraft to look at flat things which is good for ice sheets, for example, but it doesn’t do so well on things that are highly sloped. For example, like mountain regions, or quickly changing glaciers so at the edges of the ice, you get these places that are highly cracked and are moving really quickly and unfortunately ICESAT doesn’t do as well there. So we’re looking at designing new technologies to try to figure out how to do that better.

Jim Green:In thinking about the possibility of life underneath the icy crust of Europa, how could they possibly survive? And what would they look like?

Catherine Walker:That’s a great question. And I’m sure a lot of people have a lot of answers. But one of the things we can think about on Earth is that, you know, a few decades ago, I think the general idea of life on Earth was, you need sunlight, you need water, you need certain number of nutrients. But, you know, over, over the last few decades, even this is new, sort of science, you know, we know now, things called extremophiles have been found things that live in, you know, some of the hottest places, the bottom the ocean at those vents, those sort of mid-Atlantic ridge vents, never would have thought of that before, you know, a few decades ago, that that would be a place that anybody would like to live.

Catherine WalkerBut, you know, we found organisms that not only don’t need sunlight, but then they can also live with these high-high-heat places in the darkness, and things like that. And we also found underneath the ice sheets on Earth, you know, we’ve drilled a really deep hole in the ice in the middle of the ice sheet in Antarctica, you know, 1,200 meters down, found a pocket of water, and there was literally a shrimp in there living — you know, no sunlight, no, nothing that we think of as nutrients. But he was living down there, probably with a family. And so there’s the sources of energy and things that we don’t, we still don’t know all about. And so, you know, I imagine at Europa, there’s very similar sort of resourceful organisms that can figure out how to survive and how to sort of turn that, any energy they can get into something they can live on.

Jim Green:Yeah, that would be fantastic, if we could find life in the ocean of Europa. It would tell us that, that life is a pretty universal thing, and perhaps all over our galaxy.

Jim Green:Well, Catherine, I always like to ask my guests to tell me what was the person, place or event that has gotten them so excited about being the scientist they are today. And I call that event a gravity assist. So Catherine, what was your gravity assist?

Catherine Walker:So I guess I have a two-fold gravity assist, I think I like to think of it as maybe my exit from low-Earth orbit. And then the next one was a, you know, slingshot around the moon or something like that. So the first one that I can think of, that sort of got me into getting interested in being a scientist, was, this is gonna sound silly, but I saw the movie Apollo 13, when I was about 10 years old.

Catherine Walker:I told my parents, I said, “I’m gonna be an astronaut,” which is basically the same as most 10 year olds, probably. And then unlike most other folks, I think I’d never let that go. As I continued through my career, I said, “Oh, you know, I liked the ocean. I like geology.” And I said, “hey, those things would actually help me be an astronaut someday.” And so I never gave that up. Later in my career, once I was getting through college and things like that, I got an internship at the University of New Hampshire with a scientist named Antoinette Galvin, and she was the PI on the, one of the instruments on the STEREO mission. And I got a summer internship there. I was excited. It was close to home.

Catherine Walker: And it was exciting because it was an actual mission at NASA, and I was, you know, finally working on a NASA thing. And she was very kind to me, I’d never had any sort of spacecraft experience before. So, you know, it was perfectly reasonable if she was sort of like, “Hey, do this summer project, and then you’re done.” But she, you know, she was super helpful and encouraging. And she kept me on after the summer. She said, “Would you like to keep working with us, we’d love to have you on the team.” And she was just one of those people that didn’t have to be that nice. But she was and she was interested, I guess, in you know, sort of paying it forward in the in the field. And so that really got me started at NASA. And got me even more excited about being involved in stuff like this. So yeah, she’s, she’s the person that sort of pushed me forward.

Jim Green: That’s fantastic. Well, Catherine, thanks so much for joining me and talking about a fantastic look at water, not only as liquid but as ice.

Catherine Walker:You’re welcome. Thanks so much for having me.

Jim Green:Well, join me next time as we continue our journey to look under the hood at NASA and see how we do what we do. I’m Jim Green, and this is your Gravity Assist.

Credits

Lead producer: Elizabeth Landau

Audio engineer: Manny Cooper