Episode description:

NASA is an exploration agency, and one of our missions is to know our home. In the 1960s, NASA astronauts orbiting the Moon captured a revelatory view of Earth. Today, NASA explores our home planet with a fleet of dozens of spacecraft. In this episode–the first in a miniseries all about Earth–we take in the view from space with Karen St. Germain, the director of NASA’s Earth Science Division.

[Music: Curiosity by SYSTEM Sounds]

PADI BOYD: Welcome to NASA’s Curious Universe, a show full of wild and wonderful adventures for anyone, especially first-time space explorers. I’m Padi Boyd.

JACOB PINTER: I’m Jacob Pinter, and I want to start this episode hot with a pop quiz. Padi, no cheating, because I know you know the answer.

PADI: How about I ask the question then? Here goes: What planet does NASA study more than any other?

[Music: Everyday Mystery by Andy Hopkins and Dean Mahoney]

JACOB: OK now, think about it. I’ll give you a second. You know, I’m not going to play the Jeopardy music, but, like, hum it to yourself or something.

PADI: OK, that’s long enough. The answer is, drumroll, please …

JACOB: Earth! I mean, it’s a special planet for us because we live here. Plus, of all the planets out there, Earth is the only one that we know for sure has life.

PADI: NASA has a fleet of more than two dozen satellites studying Earth from space. Plus, we work with other government agencies, international partners, commercial partners, universities, and all kinds of groups that can use our data.

[Music: Three Voices by Alexis Francois Georges Delong]

JACOB: We are kicking off a five-part series, celebrating NASA’s exploration of our home planet. This is episode one. Over the next few weeks, you’re going to hear how NASA tech that was developed to map the Moon is now giving farmers detailed data about their crops.

PADI: We’ll explore the oceans, as only NASA can. Our satellites track microscopic organisms from space and measure changes in sea level across the globe.

JACOB: And we’ll get the inside story from NASA’s decades of research into one of the world’s biggest environmental challenges—ozone depletion—and how NASA satellites and airplanes work together to study air quality around the world.

PADI: But first, we have to go back to the beginning. This story starts a long time ago and a long way from Earth: 240,000 miles away.

BILL ANDERS: The impact crater with uh, just prior to the subsolar point on the south side, in the floor of it … (fades out)

PADI: In December 1968, NASA astronauts orbited the Moon for the first time. This was the Apollo 8 mission, which paved the way for the first human landing on the Moon.

JACOB: Astronauts Frank Borman, Jim Lovell, and Bill Anders were farther away from our home planet than any person had ever been. As they rounded the far side of the Moon, the astronauts saw an incredible sight out the window.

BILL ANDERS: Oh my God, look at that picture over there! There’s the Earth comin’ up. Wow, is that pretty!

[Music: Beyond the Horizon by Nicholas Smith]

PADI: It was Earth, lit by the Sun, rising above the desolate lunar surface. Inside the cramped command module, the astronauts scrambled to get their cameras.

ANDERS: You got a color film, Jim? Hand me a roll of color, quick, would you?

JIM LOVELL: Oh man, that’s great.

ANDERS: Hurry.

LOVELL: Where is it?

ANDERS: Quick.

JACOB: Borman, Lovell, and Anders saw Earth as a smooth blue ball, brushed with white streaks. It looked small. And beyond Earth there was only blackness.

LOVELL: Hey, I got it right here.

ANDERS: Let me get it out this one, it’s a lot clearer.

LOVELL: Bill, I got it framed, it’s very clear right here!

[shutter click]

LOVELL: Got it?

ANDERS: Yep.

LOVELL: Take several, take several of ’em! Here, give it to me!

ANDERS: Wait a minute, just let me get the right setting here now, just calm down.

LOVELL: Take –

ANDERS: Calm down, Lovell!

LOVELL: Well, I got it right – aw, that’s a beautiful shot.

JACOB: When technicians on Earth developed the film, they saw a shot of gray Moon craters, a distant Earth, and the blackness of space—so much space. Today, that iconic photo is known as Earthrise. It was a powerful symbol that showed why we need to protect our planet. In fact, less than a year and a half after the photo was taken, the world celebrated the very first Earth Day. Today, Bill Anders is credited as the photographer, although for decades his commander, Frank Borman, insisted that he actually took the picture.

PADI: Bill Anders would later say that seeing Earth so small and so far away drove home that we live on a “fragile little ball”. And he summed up the Apollo missions this way: “We came all this way to explore the Moon, and the most important thing is that we discovered the Earth.”

KAREN ST. GERMAIN: As you stand on the surface of the Earth, you’re looking around at your environment, and it may be lovely, and you look up at the sky, and it’s this beautiful blue, and maybe there are clouds, and it all looks lovely out there.

[Music: Overview Effect by Jan Telegra]

PADI: This is Karen St. Germain. She’s the director of Earth science for NASA.

KAREN: But when an astronaut gets to space outside of our atmosphere and they look around, it looks cold and deep and dark, and the Earth looks like this beautiful gem.

PADI: There’s a name for this feeling: the overview effect. Astronauts have described it over and over as we continue to explore space. Most of us will never have that experience ourselves. But with NASA’s view from space, you can recreate the feeling of looking at the entire Earth.

JACOB: And lucky for us, there is a place where you can sit and let that view wash over you. So of course I asked Karen St. Germain to meet me there.

KAREN: Well, we are standing in the Earth Information Center in NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C. And this is a space where we share with the general public the Earth as we can see it from space and what that means.

JACOB: Standing in the Earth Information Center is the closest I’ve ever felt to holding the whole world in my hands. And I should add, it’s open to the public and it’s free, so anyone can do this.

[Music: Garden of Synapses by Jan Telegra]

There is a super wide video screen that takes up most of a wall. It’s like a dashboard showing Earth’s vital signs. I watch animations showing the latest measurements of air pollution and weather patterns, and changes in sea ice and ocean level, all across the planet.

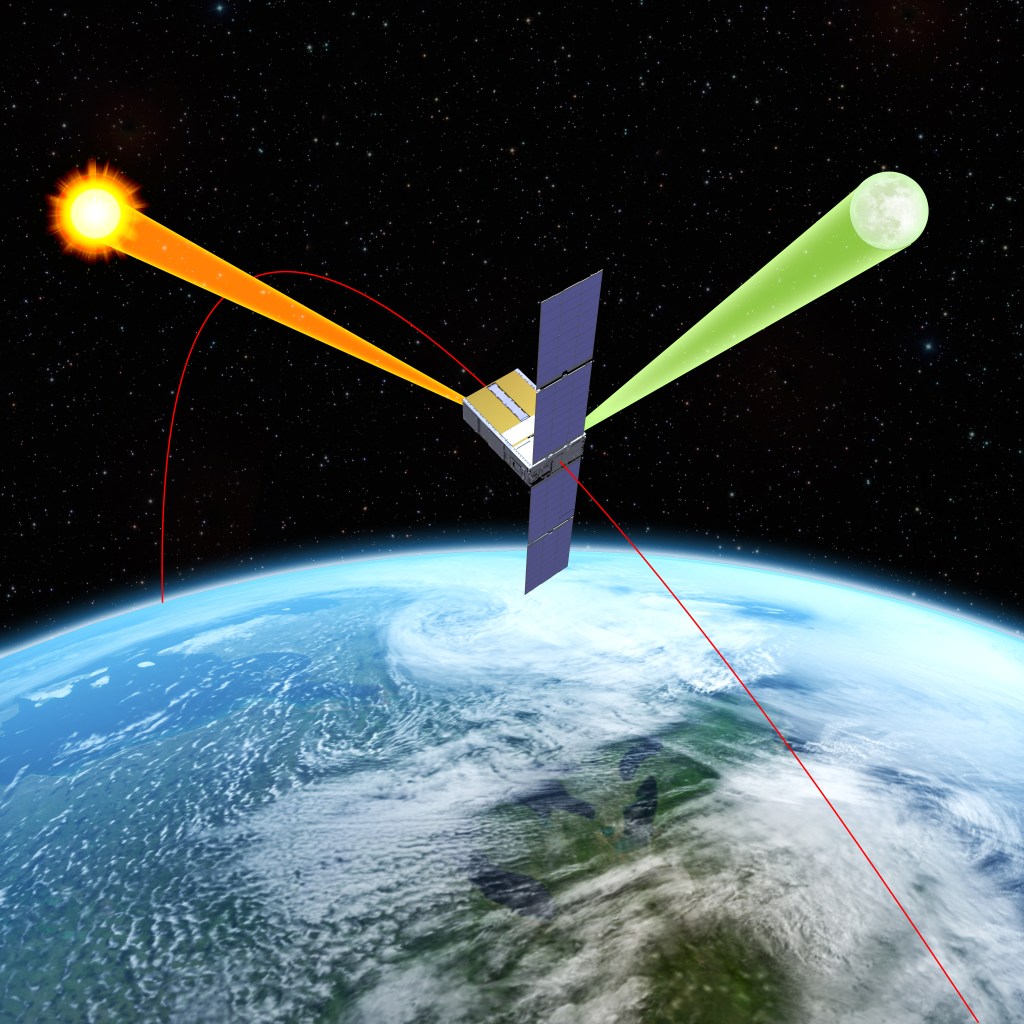

PADI: The technique that makes this possible is called remote sensing. From hundreds or even thousands of miles above Earth’s surface, NASA satellites take in tons of information. They’re equipped with an array of imagers, radars, and other instruments. And while we get a global view of the planet, we can also see incredible details. A mission called NISAR, which is expected to launch in 2025, will show changing features on Earth’s surface as small as one centimeter.

JACOB: When you look at Earth like this, you notice connections that we sometimes take for granted. Like, we all know about the water cycle. Water evaporates from the ocean, it condenses in the atmosphere, it rains onto land, it flows down rivers and streams, and then the cycle continues. But it’s striking to see just how much land, sea, and air are linked. Karen points out one of her favorite views of Earth. It shows ocean currents around the world, color coded by temperature.

KAREN: So think of a rainbow of colors all in motion, depicting how the oceans move but also how they carry heat. If the oceans didn’t do what they do, life as we know it would not be possible, and I didn’t actually know that until I started this job. I mean, I really didn’t viscerally understand it until I started this job and realized it’s the oceans that move heat. And it’s, it’s, it’s a compelling, compelling—it’s beautiful, and it’s the story of life. What could be better?

JACOB: Do you ever—like when you need inspiration, do you just take a walk and come down here and sort of sit? And …

KAREN: I do. In fact, you know, not every day is a great day, and often, on my way out of the building, I’ll stop and I’ll sit on that bench and I’ll just watch the data before me. So it’s—I do. I draw inspiration and real joy, actually, from seeing the Earth as we can only see it from space.

JACOB: Should we head up?

KAREN: Yeah let’s head up.

JACOB: OK. I’ll follow you guys.

[Music: Move As I Move by Jan Telegra]

JACOB: To keep the conversation going, Karen leads me to her office a couple of floors higher. Before she joined NASA, Karen was a research scientist and then held leadership positions at a couple of different government agencies. In her office, she keeps mementoes of some of her greatest science adventures. There was the time she sailed from South America to Antarctica on an icebreaker.

KAREN: And so this was a case where I was working to demonstrate a technique to remotely measure sea ice thickness …

JACOB: The time she snowmobiled across glaciers in Greenland.

KAREN: Greenland is going to be the first place where we start to see some changes in ice sheets …

JACOB: And a photo from where it all started: Karen as a graduate student, stepping out of an aircraft designed to fly directly into tropical storms.

KAREN: This is the certificate they give you when you fly through the eye of a hurricane. I’m not sure it ages well because it says, “To all men, be it known that Karen St. Germain has this day … “

JACOB: Karen earned this certificate in 1988 by flying along with NOAA’s Hurricane Hunters. Now, we’ve had a couple of Hurricane Hunter pilots on Curious Universe, and I can tell you, that job is not for the faint of heart. Karen was studying Hurricane Gilbert. It was a category five storm that rumbled across the Caribbean Sea and made landfall in Mexico. And she says seeing that storm firsthand stuck with her forever.

KAREN: It was a monster of a storm. It was a real beast—the lowest pressure we had ever measured in this hemisphere. The hurricane force winds extended for hundreds of miles, and in particular when it crossed the Yucatan Peninsula, it was enormously damaging—billions of dollars in damage—but more importantly, hundreds of lives lost. And some of those people were swept out to sea and never found, which I didn’t find out about until I was back on the ground in Florida. So I had this juxtaposition of this really interesting science work but then making the connection to human lives and the science really matters. And I, that day, said that should never happen again. People should never be caught unaware or unprepared. That was the moment when I understood I could do this fascinating, interesting work, and it could really matter to lives and livelihoods. How could I do anything else, right?

JACOB: When and why did NASA first get involved in studying Earth, our home planet?

KAREN: Well, the very first inkling that we could study our home planet from space and that it would be valuable was in that Apollo era, with those first photographs of the Earth taken from space. But shortly thereafter, there were a couple of imperatives, at least on the civil side of government. One was weather, seeing clouds and storms forming. Remember, before we had satellites, you would have no way of knowing that a hurricane was forming out at sea—or very little warning in some cases. So that was one of the earliest missionaries, and the other one had to do with food, actually. In 1972 we launched the first satellite that would become the Landsat series, and that first satellite was launched amidst a global food crisis, so the idea was to use that vantage point of space to understand what is growing around the world, what is the state of health of those crops. And that’s a mission that we continue to this day in partnership with USGS, critically important for food security around the world. So those were the first two that really got us off to the races.

JACOB: Why is it important for NASA to continue to do this work, and what is, like, NASA’s slice of that research?

KAREN: Well, there’s a lot that we don’t understand about our home planet.

[Music: Robot Reborn by Nick Herbertsen, Tord Jungsten, and Danny Cullen]

We understand, I would argue, more about the surface of the Moon than we understand about how our oceans work, particularly the deep oceans. So there’s always more to learn about home, and there’s an awful lot of synergy. We use the same kinds of science to understand the Earth’s atmosphere and environment as we would use to understand what would have to happen for humans to live on Mars. The same sensing technologies work on Earth as work in space, and it’s that exploration mission. Our satellites allow us to see parts of the Earth that are still relatively unexplored, parts of the Earth that are difficult to get to, like the Arctic. We can use this vantage point of space to continue to explore our home planet too.

JACOB: Can you say more about that sort of interplay between studying Earth and studying other planets? Like, one of the examples I was thinking about before I was coming to meet you is that we’ve studied Venus well enough to know that it’s got tons of carbon dioxide and at some point must have had some kind of runaway greenhouse effect to get it that way. So like, what can you learn from other NASA scientists studying other places in the solar system or beyond—what can they learn from you, and what can you learn from them?

KAREN: Yeah, this is a question I love. This is a really exciting area of collaboration between our Earth science team and our planetary science team. A lot of the models have common roots. The first models we used to consider planetary exploration were built on models here on Earth, and there have been times in the past where the fact that we couldn’t use our models to explain something happening on another planet pointed to an error in the model that actually matters here on Earth too, right? The laws of physics are the laws of physics. The laws of chemistry are likewise consistent. So having lots of environments to study in the solar system actually just makes our understanding that much richer and that much deeper. So yeah, there’s a lot of room for collaboration there.

JACOB: You know, you mentioned the Landsat program going back 50-something years. So by now, there’s this long record of the Earth and how it’s changed over that time. Tell me a little bit about one, just the value of having that. And what do you see when you look at those 50-something years all together?

KAREN: Yeah, that is one of the most fascinating things and another part of NASA’s job that is really important. We steward, we take great care with that data record, and that tells us a lot about the processes by which the Earth works. The water cycle is a great example.

[Music: A Closer Look by Marc Aaron Jacobs and David Wittman]

So all of the water that we need to live on land, to grow our food—to wash our dishes and ourselves and drink—all of that water that we need to live on land comes from the oceans, and it gets delivered to us by the atmosphere. And then eventually it makes its way back into the oceans. That’s—in a nutshell, that’s the water cycle, and we can see how that is changing over the years, in some cases intensifying. You know that in many areas we’re seeing more or more intense flooding. So it’s only by having a record that you can see, Ah, the system is changing, and that’s really important to understand, because once you understand, you can capture that understanding in models. And once you have a model, you can start looking out into the future. These models give you high beams to see what might be coming, and that’s really in many ways, where the power of science gets unleashed. Because now you can inform decisions, right? So there are a lot of ways in which that record is really useful, but giving us those trends and those ways to look out into the future is one of the most impactful.

JACOB: So I’d love to hear more about some specific missions going on now. I know that there are many, and I know that asking you to pick favorites is probably not going to get me anywhere, but if I do ask you, do you have favorites? Or, you know, how can you sort of like, narrow down this big portfolio into some that we should pay attention to?

KAREN: Oh man. It’s really, really tough. We have missions like TEMPO, and that’s mapping out air quality. And I love the fact that our data is getting right into the hands of managers in cities, helping them figure out when to warn people about air quality so people can make good decisions for themselves. We launched a pair of missions just a couple years back. One of them is called SWOT, and the other one’s called PACE. And I say that they are a pair because the SWOT mission is observing water height—so sea surface height, but also rivers, reservoirs, lakes—at a level of fidelity we’ve never seen before, and this allows us to see ocean currents and eddies from space that we’ve never been able to see. So that instrument is all about the physical processes of the ocean, but its partner, PACE, is seeing biology in a way that allows us to identify, not just that something is growing in the ocean, some algae, but what kind? Is it a toxic kind, or is it a delicious fish food kind, right? And so now for the first time, we can really at high—in high fidelity—understand how the physical ocean and the biological ocean work together. And that is one of the things that I’m super excited about. And I’d be remiss if I did not mention the upcoming launch of NISAR, which is going to be, you know, one of the most sophisticated radars—I think the most sophisticated radar we’ve ever launched. This instrument is going to be able to see any structural change on the surface of the Earth to centimeter scale. Maybe there was a forest that got cut down, or maybe there is a building that shifted a little bit because of an earthquake. I could carry on, but probably I shouldn’t.

JACOB: Another thing that you’ve mentioned a little bit is the way that NASA takes that science and then applies it to some people who can use it, right? So you have all of this data. How do you find the people who it’s really useful for? And how do you, you know, sort of take your peanut butter and their jelly and mix it together so that they can have something to work with?

KAREN: You have to go to where the users or the potential users are meeting, You have to learn about what’s important to them. It’s amazing how rich the conversations are when you ask a person—whether it’s a farmer or a city manager or a water manager in the western states or a park ranger—when you ask them, What are your hardest problems? What are the most challenging decisions you have to make every day? And what information would make a big difference to you if you had it? So I’ll give you one example just to illustrate what I mean. So I mentioned the SWOT instrument, and that measures sea surface height. Great. So we know what sea surface height is today. If I am a mayor in a coastal city, that might be interesting. But what I really am worried about is what’s coming five years from now, right, because I’m making infrastructure investments. So when we can transform sea surface height to flooding days they should anticipate, now that’s information that they can act on. The more runway people have to make decisions to prepare for what we think is the change that’s coming, the better for all of us.

JACOB: When you were on the road talking to farmers and water managers, was there, like, a conversation or two that has just stuck with you since then, that’s been like replaying in your brain?

KAREN: Yeah, there’s one conversation in particular that I will never forget. We were visiting—this was probably two years ago. We were visiting farmers in Iowa. These are mostly corn farmers, but they do some other crop rotation, and they’re mostly family farmers. Now, to paint the picture, these family farmers are running million-dollar operations, multi-million dollar operations, so don’t think, you know, your backyard. And many of them grew up in farming families.

[Music: Robotica by Carl David Harms]

So they were talking about some of the conditions, the changes in the growing conditions that they’re facing. This has to do in many cases with the variability in the spring and the fall. It gets warmer earlier, but then there’s a late frost. So knowing exactly when to plant, for example, is a real challenge for many farmers around the country. These Iowa farmers said—one in particular, Jason, said—the rules I learned to farm by, from my parents and my grandparents, don’t work anymore. Every year I adjust. I try something new. But I don’t know if it worked until I get to the end of the season and I get to measure my yield and the quality of my crop. That means I have one learning data point per year. And he said, at one data point per year, I cannot learn fast enough for me to be sure that I can hand this farm to my kids. That conversation was the catalyst for a discussion about a project where we might be able to set up a virtual farm, where the farmer could come in and, using crop models and our data, run a lot of if/then scenarios with what’s probably coming weather-wise and temperature-wise and different choices that farmer has on what to plant and how to manage it and learn so that they can make a better decision this year.

JACOB: Did you ever follow up with this guy, Jason, and hear—

KAREN: Oh yeah. And we’re kicking off the project with, in partnership with the Iowa corn growers. So yeah, so these conversations, particularly the ones that stick with you, can really be the catalyst for some neat ideas.

JACOB: We all live on Earth, obviously, but most of us don’t get to see it the same way that you and other NASA scientists get to see Earth a lot of the time. Do you find that there is something that regular people outside of NASA either don’t know about our planet or don’t understand or even, like, take for granted that we should just know?

KAREN: The biggest thing would be just how awesome this planet is, how it works.

[Music: Nishimura by Clément Durand]

It’s almost as though it’s living, right? The—how all of the systems work together, it’s beautiful, and it’s so interesting, right? I mean, most of us grow—I mean, I didn’t know this until I got into this business, right? We all grow up in a place. We all love our hometown, our home region, and we see the beauty at the human scale. But the sense of awe when you can see the beauty at a global scale is something I wish I could share. Yeah.

JACOB: Have you been able to make people see that?

KAREN: I will tell you, one of my favorite things to do is sneak into the Earth Information Center and not tell anybody who I am and just watch. To see little kids going into the immersive experience and running out and saying, I want to go again!, just like they do at an amusement park, right? Or watching children and their parents get completely absorbed in the animations. I love that. So I think the answer is yes, and the only trick is how to get that experience for more people.

JACOB: I have one last question for you. What are you still curious about?

KAREN: Wow. That list is way too long. I have spent my life being curious. It’s a great pleasure, actually, to go through life and to have a job like this that allows me to be curious and learn every day. What an incredible gift.

[Music: Eliza’s Daydream by Tim Harvest and Zach Rowan]

I am most curious about how humanity will use the knowledge we’re producing. I think there’s a lot of opportunity there, and I’m curious about whether or not we’ll take that opportunity and run with it.

JACOB: Well, a curious life sounds like a life well lived.

KAREN: I think so.

JACOB: Karen St. Germain is the director of NASA’s Earth Science Division at NASA headquarters. If you want to see Earth the way NASA does, in partnership with other government agencies, data from the Earth Information Center are available online. Find it anytime at earth.gov.

PADI: And we’ve got more exciting stories about our home planet coming up. Get ready to explore the land we live on, the oceans that cover most of Earth’s surface, and the air surrounding it all, as only NASA can.

This is NASA’s Curious Universe. Our Earth series was written and produced by Jacob Pinter and Christian Elliott. Our executive producer is Katie Konans. Krystofer Kim is our show artist. Our theme song was composed by Matt Russo and Andrew Santaguida of SYSTEM Sounds.

Special thanks to NASA’s Earth Science team, including Mike Carlowicz and Liz Vlock. NASA is constantly developing new tools and techniques to understand how our planet works and putting these data to use to help the United States and the world. You can find more information at science.nasa.gov/earth.

If you enjoyed this episode of NASA’s Curious Universe, please let us know. We love to hear what you think, so don’t be afraid to leave us a review. You probably have a friend who lives on Earth. Why not send them this episode, so they can learn m ore about this blue marble we all call home? And remember, you can follow NASA’s Curious Universe in your favorite podcast app to get a notification each time we post a new episode.