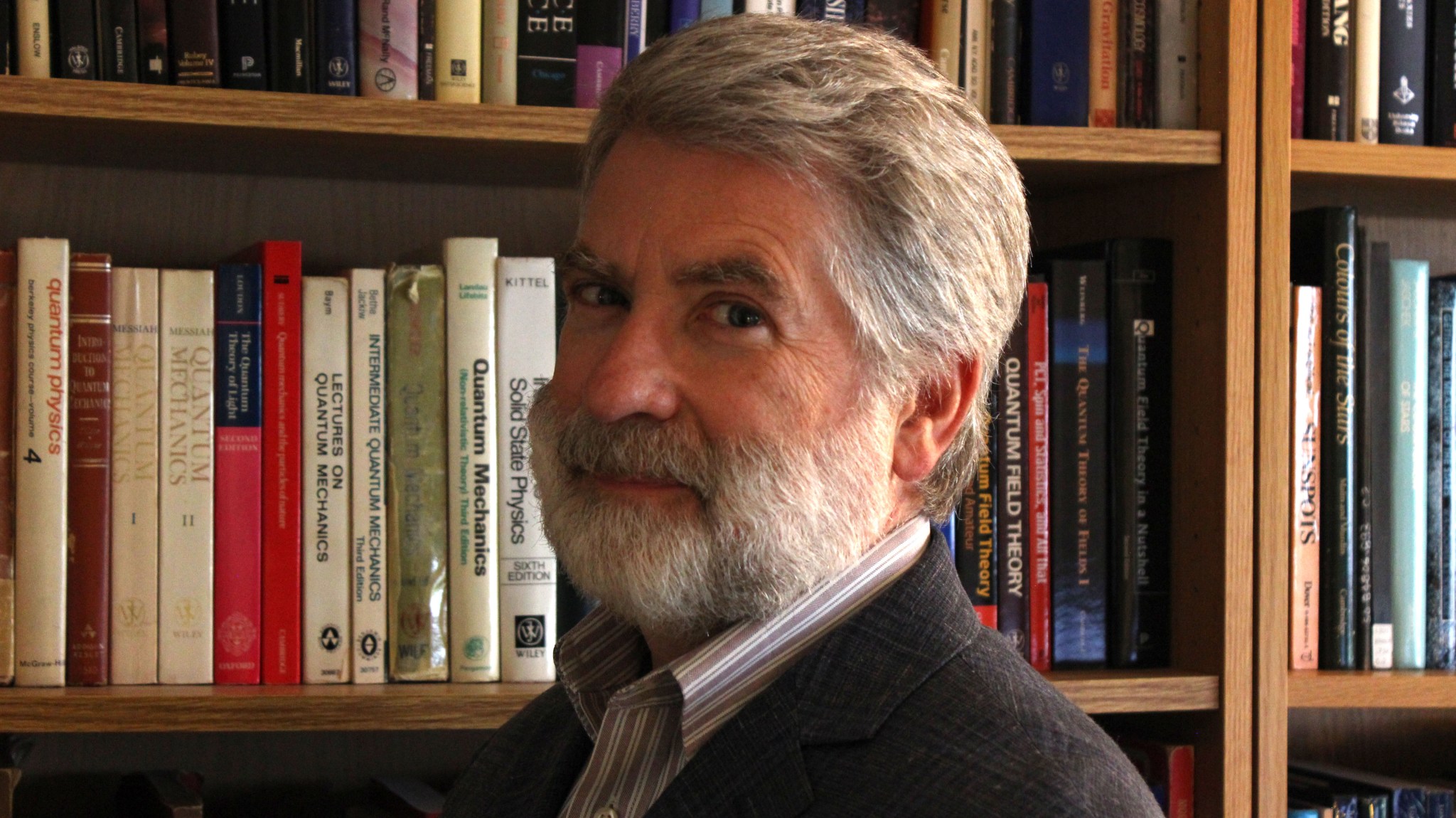

Name: Michael T. Menzel

Title: Lead Mission Systems Engineer for James Webb Space Telescope

Formal Job Classification: Mission system engineer

Organization: Engineering and Technology Division (Code 500)

What do you do and what is most interesting about your role here at Goddard? How do you help support Goddard’s mission?

I am the lead mission systems engineer for the James Webb Space Telescope. I am responsible for ensuring that this critical telescope will perform on-orbit. I lead a large team from all over the world. I report to the Goddard project manager as well as the Goddard engineering director.

What makes you unique and different from others at Goddard?

To sum up, I was an MIT physics major. I did well, I got an A average. And during summers I was not doing research, I was driving a taxi in northern New Jersey.

I have over 39 years of experience in aerospace. What makes me even more unusual is that I worked 23 years in industry for commercial and defense missions before I joined NASA over 16 years ago.

Where were you raised?

Elizabeth, New Jersey, Exit 13 for those in the know. Both of my grandfathers worked in the Bayway Refinery, which refined petroleum. I went to a Catholic school. My father was a cab driver and a meter man. My family is still there.

Where did you go to school?

I received a B.S. in physics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1981 and an M.S. in physics from Columbia University in 1986.

Please tell us about your 23 years working in aerospace on the industry side.

After I graduated from MIT, I could not afford to keep going to school. I took a job at the RCA Astro Space Division in East Windsor, New Jersey, as an antenna engineer for communications satellites. I designed flight antennas for commercial and defense communications and remote sensing satellites. I wanted to become a radio astronomer. My boss agreed to send me to Columbia for a master’s and doctorate in astronomy because I said school would help me make a better antenna. I worked full time. My boss allowed me to be in the office three days a week and go to school two days a week.

While I was at Columbia, their one radio astronomy professor left. He was the reason I wanted to go to Columbia. After he left, I got my masters and then returned to RCA full time.

After nine years as an antenna engineer, I went to the systems engineering group at RCA, which became General Electric’s Astro Space Division. I designed commercial, DOD, and civil space systems.

I’ve been in systems ever since. I love it because instead of just designing the antenna, I help design the entire system. I fell into a niche that I really like.

Around 1995, the plant where I worked closed. I moved to Maryland to become Orbital Science’s director of systems engineering. I then went to Lockheed Martin to be the deputy program manager for the Hubble Space Telescope Servicing Group.

Lockheed asked me to be their lead engineer for Lockheed’s Next Generation Space Telescope, which became the Webb telescope. Northrop won the proposal so I joined their team for about two years.

In 2004, I joined Goddard’s Webb telescope team as their mission systems engineer.

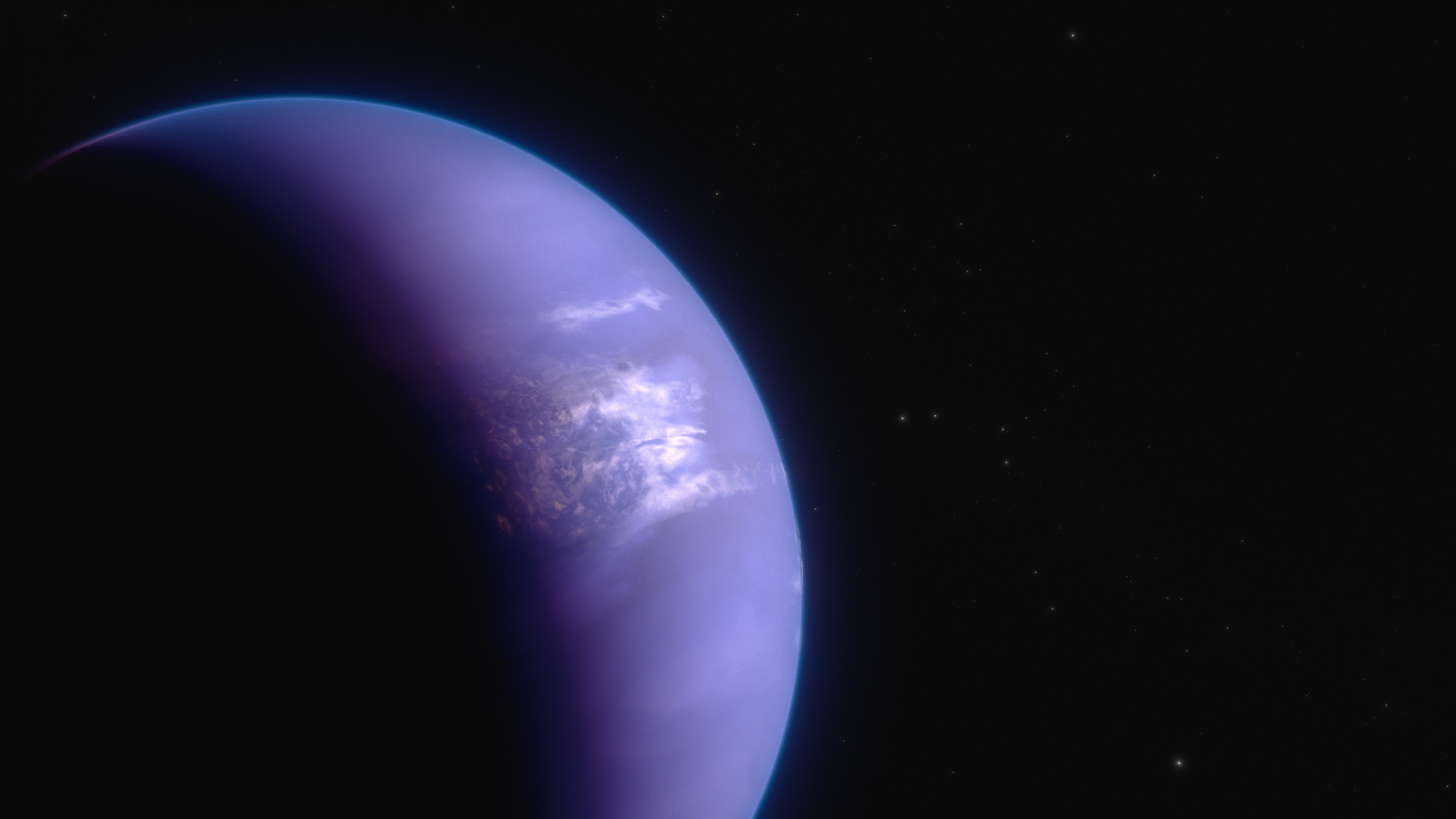

What is most exciting about the Webb telescope?

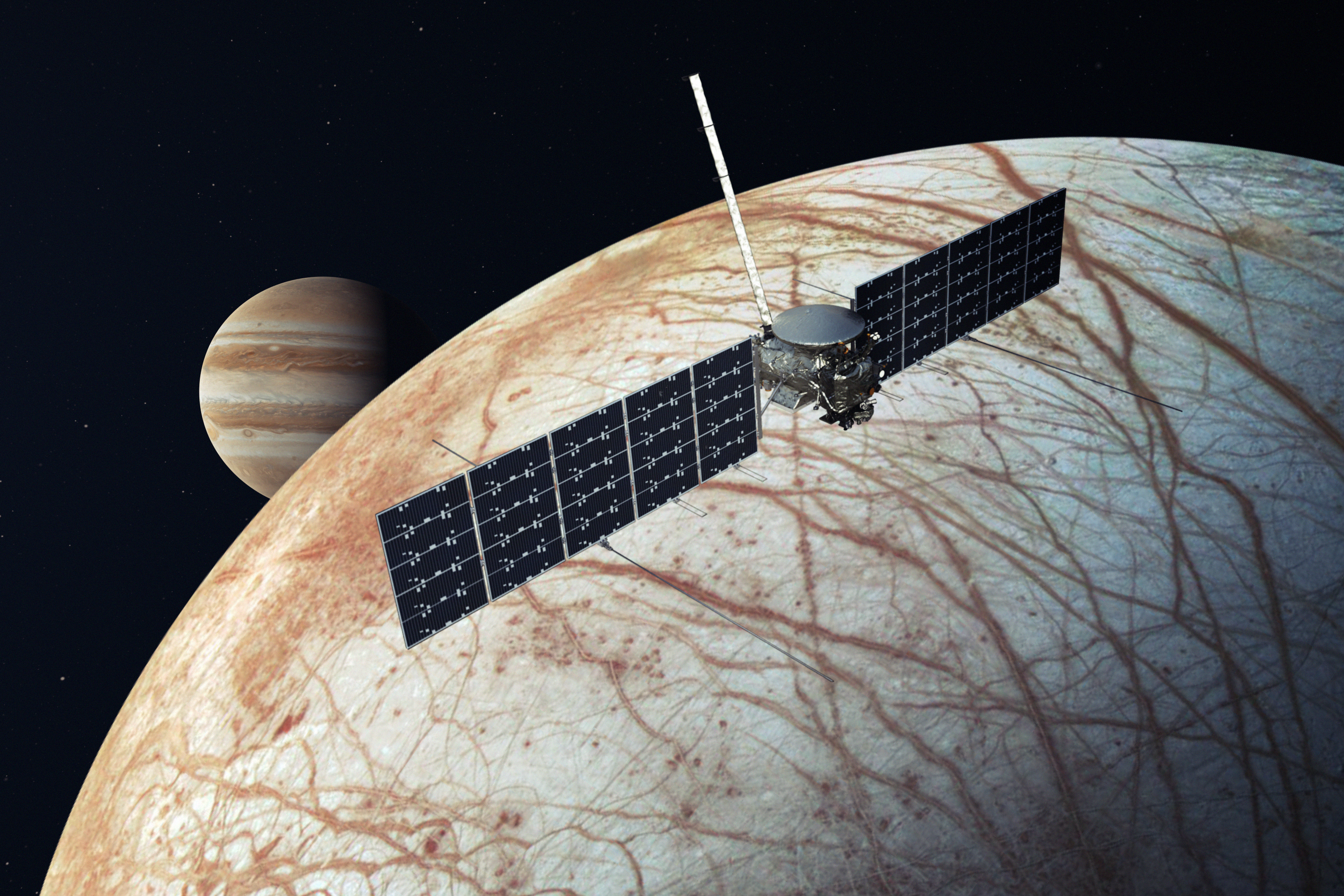

It will be the largest telescope ever put into space. It has an incredible potential for new discoveries. Even though we are designing it to do some really great science, typically what has happened in the past, as with Hubble, the telescope discovers things we never dreamed about. The possibility of Webb doing this is even more likely that it was for Hubble.

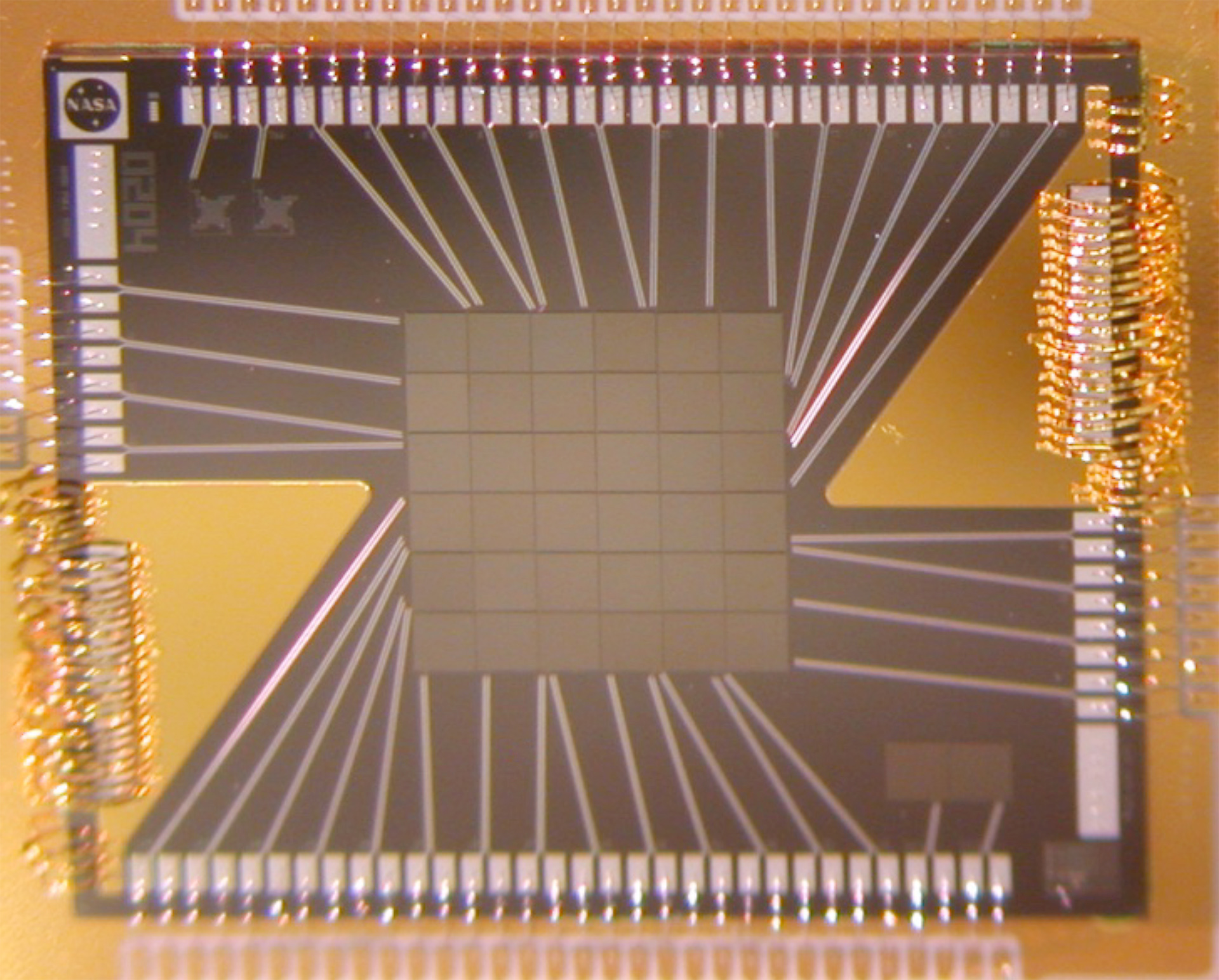

Webb will not only rewrite the textbooks for astronomy, we are already starting to rewrite the textbooks for engineering. We have already done things that have never been done before for spacecraft. For instance, we are building a telescope roughly the size of a house. We built it, we are aligning it, we will make sure it works, and then we will break it up and fold it up and then rebuild it on orbit robotically. No one has ever done this before.

Who are our Webb telescope partners?

ESA (the European Space Agency) is providing two of the four instruments and the Arianne launch vehicle. The Canadian Space Agency is providing one of the four instruments. The University of Arizona is providing the fourth instrument. We are making sure that all these instruments will work with the spacecraft and vice versa.

The telescope was integrated at Goddard and is now integrated to the spacecraft out at Northrop in Redondo Beach, California.

How do you best communicate across internationally diverse teams?

It takes a lot of collaboration to ensure that the instruments, telescope, launch vehicle and spacecraft all work together. I manage about 200 people across the world. We have a lot of meetings.

I have to establish the correct lines of communications with the correct information. Goddard fosters open communication. Open communication is important and very useful. But bad information can travel as quickly as good information, so you need the right filters to make sure that you only react to the proper information. I have to make sure that the right people are talking to the right people with the right information. We in the systems engineering group have taken great pains to do this, to make sure that the good information gets to the right people.

As a manager, what makes Goddard unique?

Goddard has a lot of talent. You need to harness that talent correctly. We have brilliant people and we need to leverage the talents they have.

A lot of what goes on at Goddard is almost organic. If I have three people, and three jobs, and none of them fit into the jobs then I redefine the jobs. I figure out how to leverage the best in each one of them. This is a good thing. This is one of the things I like about Goddard. We have a lot of passionate people who love the space program. We have a lot of flexibility in using them to their best talents.

This organic process does not typically take place in industry. In industry, this does not happen that much.

Who is the most interesting, inspiring or amazing person you have met or worked with at Goddard?

Phil Sabelhaus, who recently passed in 2017. He was the second program manager for the Webb telescope. He is the one who hired me. He was a great guy, full of passion. He just did not suffer fools well and would let you know very directly. Being a North Jersey boy, I grew up with this type of mentor. I was used to his style.

I’m not sure he taught me formally, but he was a role model for me. He was the most honest, up-front guy I ever met. He said to just always tell the truth. If people did not like it and got upset, he did not care. He always said that as long as you are honest, just say what you have to say. All you had to do is make sure you were honest.

If you were not Webb’s mission system engineer, what would you be doing?

For the earlier part of my career, I was an adjunct professor at various colleges. I taught astronomy, physics, and math. I love teaching at the college level.

For the past 15 years, I have been traveling so much that I cannot commit to being an adjunct anymore. Instead, I have given many lectures about the Webb telescope. I may return to teaching when I retire.

What has working at Goddard taught you?

Coming to Goddard, if I didn’t know how to do it already, it certainly taught me how to leverage the talents of people. At Goddard, we have the freedom to learn how to have people do what they do and like best. I have this freedom and learned how to exercise it.

What would you tell somebody just starting his or her career at Goddard?

It depends on where the person is coming from. If they are coming from industry as I did, I would tell them that things are not as structured, they are more open, which could appear chaotic. That may confuse you at first, but you will get used to it. It is better because it does not shoehorn you into a role that may not best suit you. If you give it time, you will find it is a really good system with many more advantages than disadvantages.

If they are fresh out from school, I think they would find Goddard to be very similar to the academic environments they are coming from without much adjustment.

I love Goddard. I would tell them that too.

Your next-door office neighbor is Nobel laureate Dr. John Mather. How does that make you feel?

I do not want to bother him because he is very busy, but if I have a question or a problem then I can just walk into his office.

He is the type of guy you want to win a Nobel Prize. In addition to being brilliant, he is just a great guy, a true gentleman.

I am a North Jersey boy. When I hear malarkey, I call it what it is. I just hope he can’t hear through the walls. Unfortunately I’m pretty sure he can!

What is the coolest thing you’ve ever done as part of your job at Goddard?

One of the coolest things I’ve ever done period is when I went to Scotland for Webb. I was with Dr. Mather, so they treated us very special. Because I had taught, I knew a lot of great books. Once in Scotland, I happened to visit a library with all kinds of old, valuable books that were just out for anyone to pick up and read.

I saw one book in particular. Stunned, I asked the friendly librarian if that book was what I thought it was. The librarian said yes and that I could hold the book – “Starry Messenger,” a book Galileo wrote with his original observations.

I actually held the original book Galileo himself wrote! In the U.S., it would be behind bulletproof glass.

What is surprising about you that people do not generally know?

While I was at MIT, I worked during holidays and summers at night as a cab driver since my old man was a cab driver. This was back in the late ’70s. I was probably the only MIT student at the time who went home to drive a taxi at night. That’s how I know Northern New Jersey so well.

I had the usual fares. I brought the pregnant lady about to deliver to the hospital. After 3 a.m., the bars closed and business dropped off. I was the youngest cab driver, only 18 when I started.

One morning around 3 a.m., we were all on the main corner in Elizabeth, playing cards, money all over the street, killing time. My uncle, another cab driver, was there. Then we saw a cop walk over to us. The others said to keep dealing cards. I was the dealer. I did not know what to think or do. Then the cop, a huge guy with hamhock-sized hands, put his hand on my shoulder. He asked if I was Ray Menzel’s kid. I said yes. He said that he knew my father well and that he had actually worked part time for my father.

Driving a cab was my night job. During the day, I was a tour guide for Thomas Edison’s place owned by the Park Service. I was a seasonal park ranger, GS 4 or 5. The lead ranger knew I went to MIT. Thomas Edison’s son Theodore also went to MIT. The lead ranger introduced us and Theodore and I became friendly. I was 18 and he was 88 or so. A few times, Theodore invited me to his lab and we traded math problems. He told me all these stories about his old man. I saw him once or twice each season. So a while, until I changed day jobs, I knew Thomas Edison’s son.

My grandfather Saverio Dileo was a WWII vet, Marine. He had his own private plane. I flew with him since I was 11 years old. Old Grandpa Dileo was not one for following the rules. He would open up the map in the cockpit while I flew the plane while he figured out where we were. In time, I did fly solo and was getting my private pilot license but stopped because I was traveling too much. One of my regrets is that I never got my private pilot’s license.

What is your “six-word memoir”? A six-word memoir describes something in just six words.

Ex-cab driver. MIT graduate. NASA engineer.

By Elizabeth M. Jarrell

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center