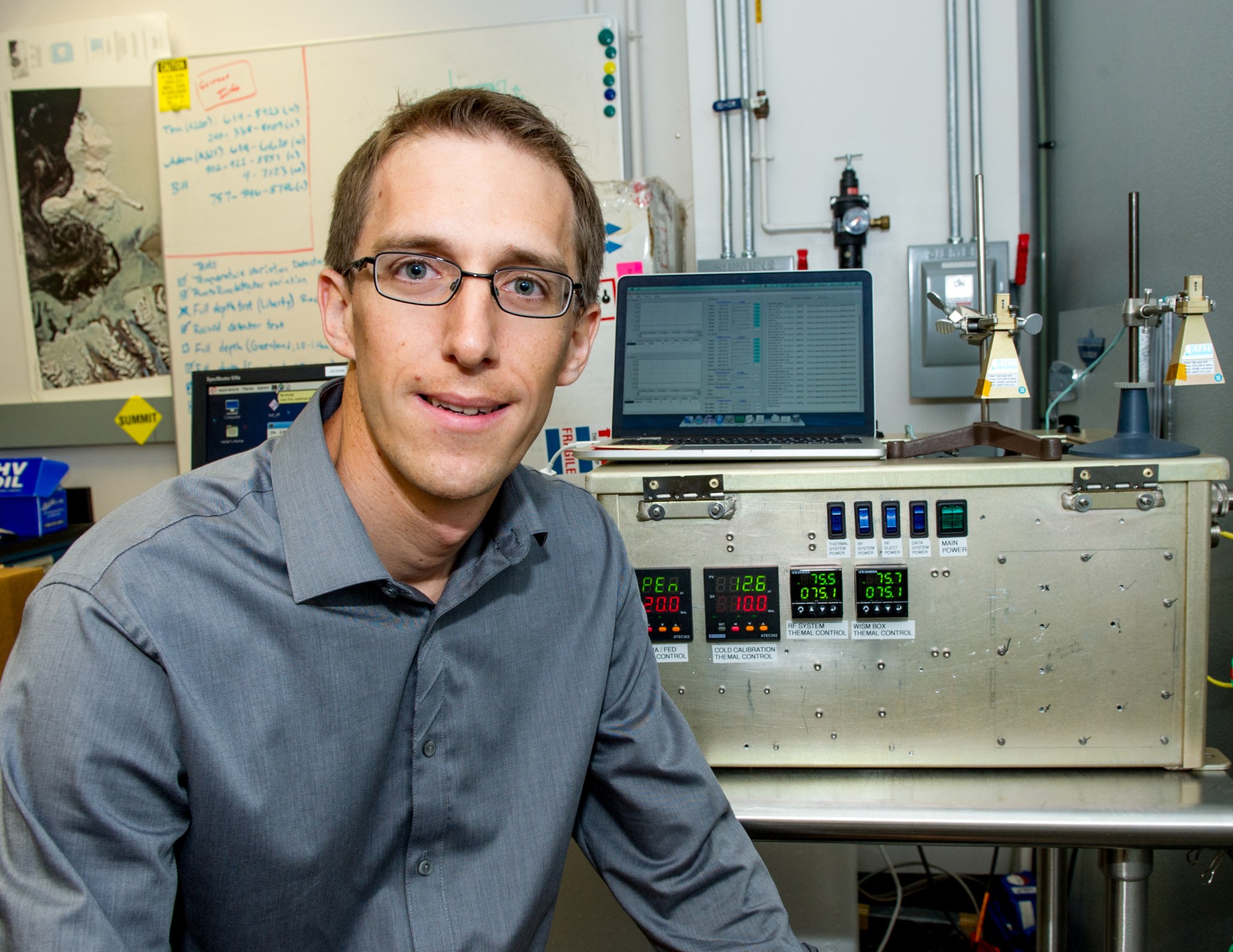

Name: Ludovic Brucker

Title: Earth scientist

Organization: Code 615, Cryospheric Sciences Laboratory, Earth Science Division, Science and Exploration Directorate

Raised in Chamonix, Earth scientist Ludovic Brucker works and plays on the ice.

What do you do and what is most interesting about your role here at Goddard? How do you help support Goddard’s mission?

I develop, evaluate and refine satellite algorithms to study the Earth’s polar regions including Greenland and the Antarctic ice sheets, sea ice and the subarctic regions. These algorithms allow us to obtain snow and ice properties from satellite observations.

These algorithms provide data mainly for climate studies and also for decision making. We need to know the state of our polar regions so that we can investigate and understand the changes happening to them. For instance, every small ice melt off of the Greenland ice sheet has a direct and important impact on sea level rise.

Please tell us about conducting field work for the Satellite Era Accumulation Traverse project on the western Antarctic ice sheet?

The winter of 2011 – 2012, I spent two months on the western Antarctic ice sheet for a NASA and National Science Foundation joint effort called Satellite Era Accumulation Traverse.

We were a team of five, including some from universities.

When it is winter here in the Northern Hemisphere, it is the summer in Antarctica but temperatures went down to minus 40 degrees F. Antarctica has no night in the summer. The temperature was never higher than 0 degree F. The wind was a game changer, since it changes how cold a person feels very quickly.

We traveled 400 miles on the ice sheet. We drove snow mobiles pulling sleds carrying our food and tents, our scientific equipment and radars. We collected radar measurements for snow accumulation. Where snow does not melt, snow accumulates each year as a stack of vertical layers. The age of a tree can be determined by looking at the rings in the truck. Similarly, the age of the snow and the amount of snow for any given year can be determined by counting the layers and measuring their thickness. Our radar can detect every layer of snow and their thickness.

To validate the layering detected by the radar, we also drilled about 20 yards into the ice to compare the remote sensing signal with the actual ice core. We consider 20 yards to be shallow drilling.

How did you stay warm?

By moving, shoveling snow, and drinking hot beverages. Truly, we are very well equipped. The United States Antarctic Program provided expedition-class gear and we wore multiple layers, all of which help us stay warm. But when I had to dig snow to measure snow properties in depth, I removed several of these warm layers because I could not afford to sweat and risk freezing my skin.

Where did you sleep?

We slept in tents. When it was very cold, we went into our sleeping bags with a hot water bottle. On Christmas day, we splurged by using two hot water bottles!

What other supplies did you carry?

We carried propane to melt snow for water and also to cook. We carried enough food for a month, satellite phones, multiple batteries and electric generators to recharge them.

How did you cook?

We carried frozen and canned food. Using a camp stove, we melted the snow for water, boiled it, and then we cooked our food.

If someone had been injured, what would you have done?

We are trained for decision making and the team leader is responsible for the final decision. We know what to do and who to contact. Above all, we are all extremely careful due to the remoteness of the location.

What were the legs of your trip to Antarctica?

From McMurdo, we flew on another United States Air Force plane to Byrd Station, a United States scientific base which is a six hour flight inland. There were only about 50 people at Byrd Station.

How did you feel when your team left Byrd Station?

After about three days, our research team of five people left from Byrd Station. I was really thrilled to be starting, but I also realized how far away we would be from anything and how careful we would have to be. I will remember that moment all my life. It really was a life-altering moment.

Where did your team conduct research?

Starting from Byrd Station, our team made a 400-mile loop in three weeks. We stopped in seven different locations for conducting detailed measurements.

Did you work on a schedule?

Typically, one day was a travel day. We dismounted camp in the early morning and traveled all day to our new location. We collected radar observations along the route. The next day was a day spent at camp taking local measurements. If we had a storm day, then we had to maintain camp. This meant that we had to remove the snow from the top of the tents and clear the doorways.

What was your most difficult storm day?

The strongest and longest storm hit us Christmas Eve. We spent the entire day shoveling snow. The wind and our constant shoveling created very high walls of snow around each tent, up to 7 feet in places.

How did you get home?

After three weeks, we returned to Byrd Station. We spent New Year’s Eve there celebrating with the station staff and other scientists. After a couple of days packing our equipment, we flew back to McMurdo Station, spent two days there and then each flew back to the U.S.

Are you in touch with your teammates?

Of course, both personally and professionally. Our team has remained in contact to discuss and evaluate the data. A summer intern who worked with me this year also helped with the data analysis.

Please describe your field work in Greenland for the firn aquifer project?

In 2013 and 2014, Clement Miege, my Antarctica teammate, and I conducted field work in Greenland. We took the same kinds of snow measurements. These data helped us understand the formation of the aquifer, which is the liquid water within the ice sheet. We were standing on the ice on top of 12 yards of snow, under that were 18 yards of ice and water, and under that were 800 yards of ice. We call the mixture of ice and water a firn aquifer.

Did you name the firn aquifer?

It was discovered during the 2011 Arctic Circle Traverse. It was not named. I do not think that the team who discovered it thought about giving it a name. It is a natural phenomenon on Earth, and there is a scientific/technical term for it. It never occurred to us to name it.

How many field campaigns do you average a year?

Usually, one campaign per year. On average, I spend two months a year on field campaigns.

What is your next field campaign?

In the spring of 2015, I am going to Cambridge Bay on Victoria Island, Nunavut, Canada, for a NASA and Canada joint project on the detection of rain-on-snow events. The rain water percolates through the snow pack, either melting the snow cover or creating an ice layer in it which in some cases prevents ungulates such as reindeer and caribou from breaking through it to access the pasture.

Earlier this year, 100,000 reindeer, 10 percent of the world population, starved to death on the Yamal Peninsula. In 2003, on Banks Island, Canada, 30,000 caribou starved to death. The indigenous populations like the Sami depend on their herds. If we can detect a rain-on-snow event, we may inform some herders who can then try to relocate their herds to a better location.

What do you think about snow days in Maryland?

I was here during the events of 2010. I received an email that Goddard was closing due to snow. At that point, we had about four inches of snow but nothing on the roads. I didn’t understand why I should leave, so I stayed working, but a guard came by and told me to leave. So I biked home and went grocery shopping on my way. I was shocked at the overall panic: there was nothing left to buy.

Why are you so fascinated by snow and ice?

I was born in northeastern part of France, but my parents moved to Chamonix when I was four years old. Chamonix is in the Alps and in that valley there is the highest mountain in Europe. There are glaciers flowing down from the mountain into the valley. We have snow from December to April.

I am a skier and an ice and rock climber, all of which likely contribute to enjoying the cryospheric sciences.

Honors and Awards: Ludovic Brucker received the 2014 Scientific Achievement Award from the NASA Hydrospheric and Biospheric Sciences “for excellent and innovative work advancing microwave research over the cryosphere from multiple sensors and through field work.”

By Elizabeth M. Jarrell

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

Conversations With Goddard is a collection of Q&A profiles highlighting the breadth and depth of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center’s talented and diverse workforce. The Conversations have been published twice a month on average since May 2011. Read past editions on Goddard’s “Our People” webpage.