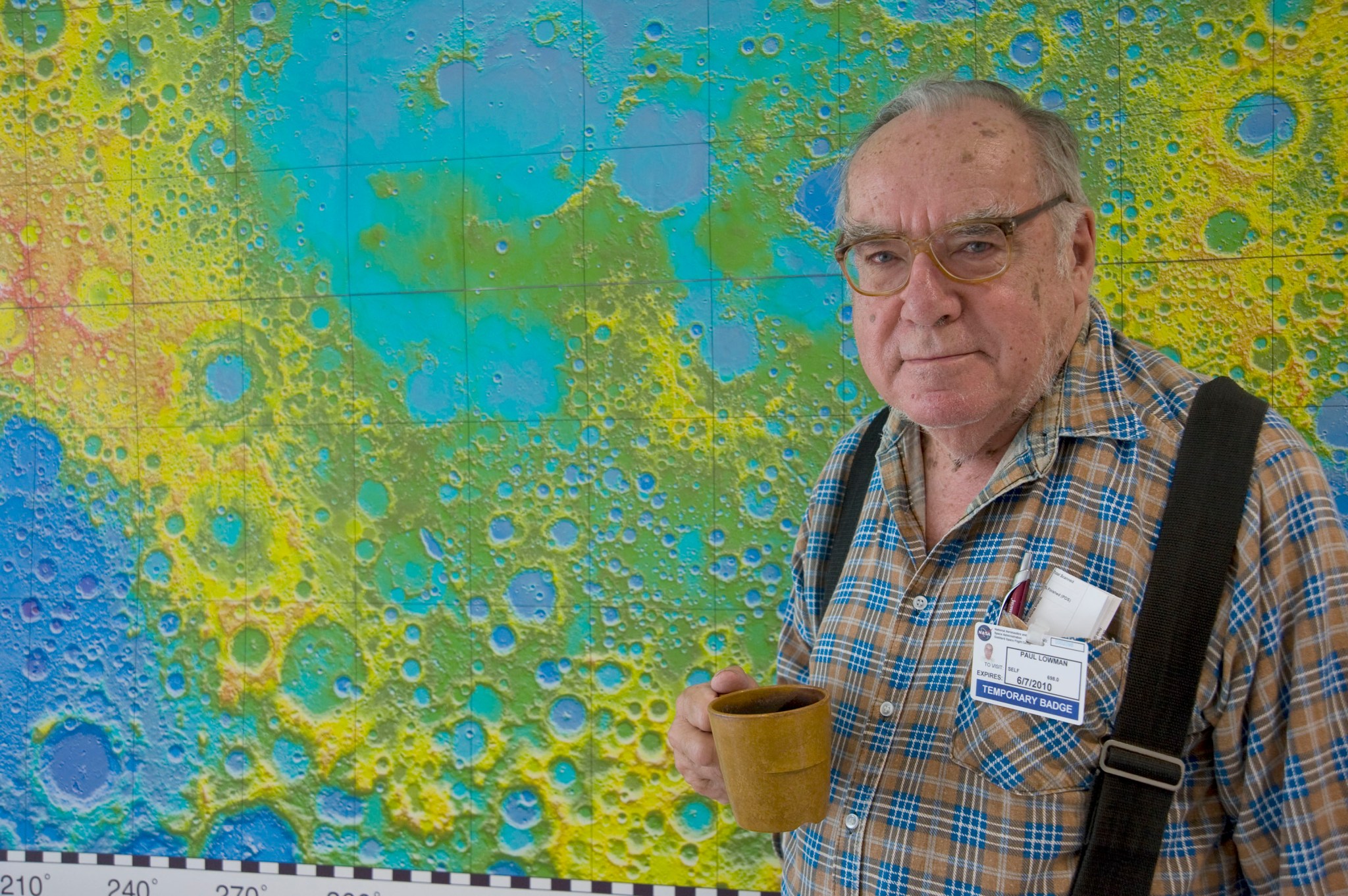

Editor’s Note: Dr. Paul Lowman passed away in 2011.

NASA was not quite a year old in 1959 when Dr. Paul Lowman Jr. started working for the agency. The geophysicist has spent 48 of his 76 years with NASA, and he still commutes daily to the Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md.

The bespectacled scientist has a wide grin, a hearty laugh, and a touch more salt than pepper in his hair. Over the years he says he has built up the reputation of being a bit of a maverick. Like most of his memories, this one comes with a great anecdote.

About 15 years ago, Lowman brought his nephew to a two-mile run held at Goddard. He introduced the young boy to Dr. Noel Hinners, center director at the time: “I said, ‘Neil, I want you to meet my boss, Dr. Hinners.’ And Noel replied, ‘Paul, you don’t have a boss. Nobody can manage you!’ We were friends from the old days, so he knew me well.”

That’s the kind of guy Lowman is, but if he’s something of a maverick, it hasn’t gotten in the way of his friendships or accomplishments.

Lowman grew up in Rahway, N.J., about 10 miles south of Newark. His father, who worked at the nearby Merck & Co. plant, instilled a love of science in his son. Books, magazines, and newspapers were constant surroundings in the household, Lowman says. He watched his first lunar eclipse from his backyard before he was 8 years old.

After high school and a two-year Army stint, Lowman pursued graduate and doctoral studies at Colorado University. As he was finishing his doctorate, the Space Age was just getting started.

NASA, though but a year old, was Lowman’s first choice for a job. There he could combine his interests in geology and the Moon to pursue new and exciting research opportunities – but his first application was turned down.

“I had … gotten back a form letter, ‘Thanks, but no thanks!'” Lowman says. But while back on the East Coast for another job interview, he decided to try his luck again.

Lowman went door to door in NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C. Someone suggested he talk to John O’Keefe, who worked in the Theoretical Division of the freshly formed Goddard Space Flight Center.

In 1959 the massive research center in Greenbelt existed only on paper. Goddard’s first offices were parceled out in buildings across the D.C. area. Lowman bused over to O’Keefe’s office in downtown Silver Spring, Md.

“O’Keefe and I hit it off perfectly from the very beginning,” Lowman says. “He was interested in a problem that I already knew something about, namely tektites and the Moon. … That really got me fired up.”

Lowman was familiar with tektites from his work in Colorado. Essentially, they are pieces of natural glass, similar to obsidian. Scientists used to think they came from the Moon, knocked off by impacts and pulled in by Earth’s gravity. However, years of research have shown tektites are likely the result of meteorite impacts on Earth.

Budding tektite research was only the beginning. In the early 1960s, O’Keefe and Lowman worked on the Sonett Report, which outlined possible experiments for the Apollo missions. O’Keefe and Lowman helped select geological tests for astronauts to perform on the Moon.

Planning these experiments was a critical early step in learning about the Moon. Scientists knew very little about the Moon before the space program, Lowman says. “We knew the Moon didn’t have an iron core,” he says. “It was pretty clear that most of the craters were impact craters, and it was a pretty fair bet that the dark areas were probably lava flows. And that was about it.”

In looking for tests to include, Lowman phoned Mark Langseth, a chief investigator at Columbia University’s Lamont Doherty Geophysical Observatory. Langseth agreed to put together a proposal.

“You could never do that today. … The scientific community has gotten so much bigger,” Lowman says. He calls that growth one of the biggest changes he’s seen in his 48-year career.

In addition to his work on lunar geology’s unknowns, Lowman was partly responsible for getting astronauts to take the first photos of Earth.

He is quick to point out the project was not his idea. “It was Paul Merifield and Dr. John Crowell,” Lowman says. Merifield, who had been a doctoral student at the University of Colorado, got the idea while he was at UCLA, from Crowell. Lowman presented the plan to O’Keefe, who was able to push the project through.

On the first Mercury missions, astronauts snapped Earth photos in what little free time they had, but soon the project became a formal experiment. Because of Lowman’s experience with geology, administrators tapped him to train the astronauts in terrain photography.

“I got three hours to tell them what I wanted done photographically, and how to do it,” Lowman says. They decided to use a Hasselblad camera with an 8mm lens, “because this was the biggest camera you could fit in a Mercury capsule and still have room for the astronaut!”

Gordon Cooper’s flight on Mercury 9 produced the first geologically useful images. Cooper’s photographs of Tibet were of high enough quality for Lowman to begin drawing a map of the region. “From then on, we were off and running,” he says.

These early photos were a far cry from the quality of later satellite images, but they were the first time someone pointed a camera down at Earth to look at something other than weather patterns.

Like millions of people around the world, Lowman was glued to his television screen the evening of July 20, 1969. What drew Lowman’s interest was when Buzz Aldrin said, “Picking up some dust,” just prior to touchdown.

“This was the first actual physical contact with the Moon,” Lowman says. “Once they got that close, I knew they were going to make the landing.”

With the end of the Apollo program in the mid-1970s, Lowman moved from terrain photography to geophysics and began work on a tectonic activity map of the Earth, showing fault lines and sites of volcanic activity over the last million years.

He finished his first map in 1976, and has been updating it ever since. Lowman initials his maps the way artists sign their paintings. That way he can keep track of where they appear. Lowman is possessive of these maps and doesn’t hesitate to call textbook publishers if they make mistakes.

Lowman has accomplished much during his Goddard tenure, but that doesn’t mean he’s thinking of calling it quits. “I plan to work for NASA … as long as my health holds up, or until I get run over!” he says. Lowman bikes to work most of the time.

The Moon’s persistent mysteries and Lowman’s lunar enthusiasm have led to his current project. “There is a burning need for a usable book on the geology of the Moon,” he says. “I think it’s going to be a real blockbuster, because there’s nothing like it now up to date.”

The Moon has revealed but the smallest fraction of its secrets, he says. There are many geological features that scientists have known about for decades, but in some cases, they are still puzzled as to what they are, or where they came from.

For example, Apollo 15 and 16 took along sensing equipment that detected the presence of radon in some locations. “Radon has a half-life of only a few days,” which means it breaks apart shortly after it appears, Lowman says. “So, if you’re seeing radon, it must’ve just come out of the Moon.”

That seems to buck the notion that the Moon is a dead world, he says. “The more you learn, the more complicated it gets.”

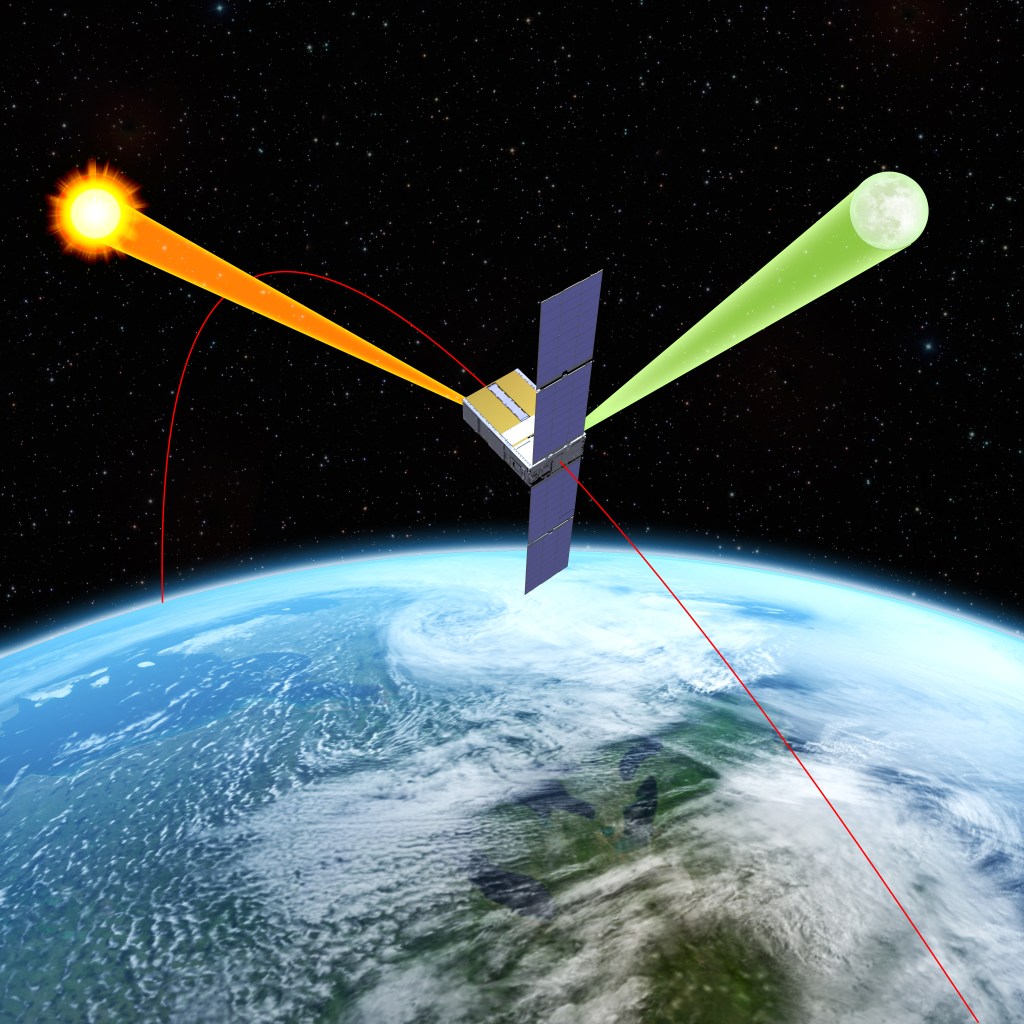

That’s one of many reasons he calls future Moon missions imperative, and one of many reasons why he’s pleased be involved with the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, scheduled for launch next October. Among other things, LRO will scout possible landing sites for future manned missions.

To Paul Lowman, the Moon is just as exciting now as it was when he saw his first lunar eclipse as a boy in New Jersey, as it was when the Apollo 11 Lunar Module blew out dust clouds on its descent. Lowman is glad we’re on our way back and thrilled to be part of making mankind’s return a reality.

By Rob Garner

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.