Name: Ernest T. (Ernie) Wright

Title: Science Visualizer

Organization: Scientific Visualization Studio, Science Directorate (Code 606.4)

What do you do and what is most interesting about your role here at Goddard? How do you help support Goddard’s mission?

I work with scientists to put their data into context. We show where that data is located and when it occurs in time. Basically, I make films out of scientific data, cinematic scientific visualization, using the same software that Hollywood uses.

How did you learn to be a visualizer?

I’m mostly self-taught. I’m still learning from my studio colleagues. When I started more than 30 years ago, there weren’t many formal programs in scientific visualization. I just loved using computers to make art that expressed my strong interest in science and space, and I found I had the necessary programming talent to translate actual data into visual stories. I freelanced while being a stay-at-home dad – working from home like a lot of us do now! When my kids got older, I went back to school and finished a bachelor’s in programming at the University of Maryland.

How did you come to Goddard?

Someone I worked with let me know Goddard was hiring visualizers. I’ve always lived nearby – I did a summer program at Goddard while in junior high – and I’d talked with someone from the studio on a Usenet newsgroup, so I knew the studio was a place I would love to be. In 2008, I was hired to work with the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), which is mapping the surface of the Moon.

What are some of the projects you are most proud of?

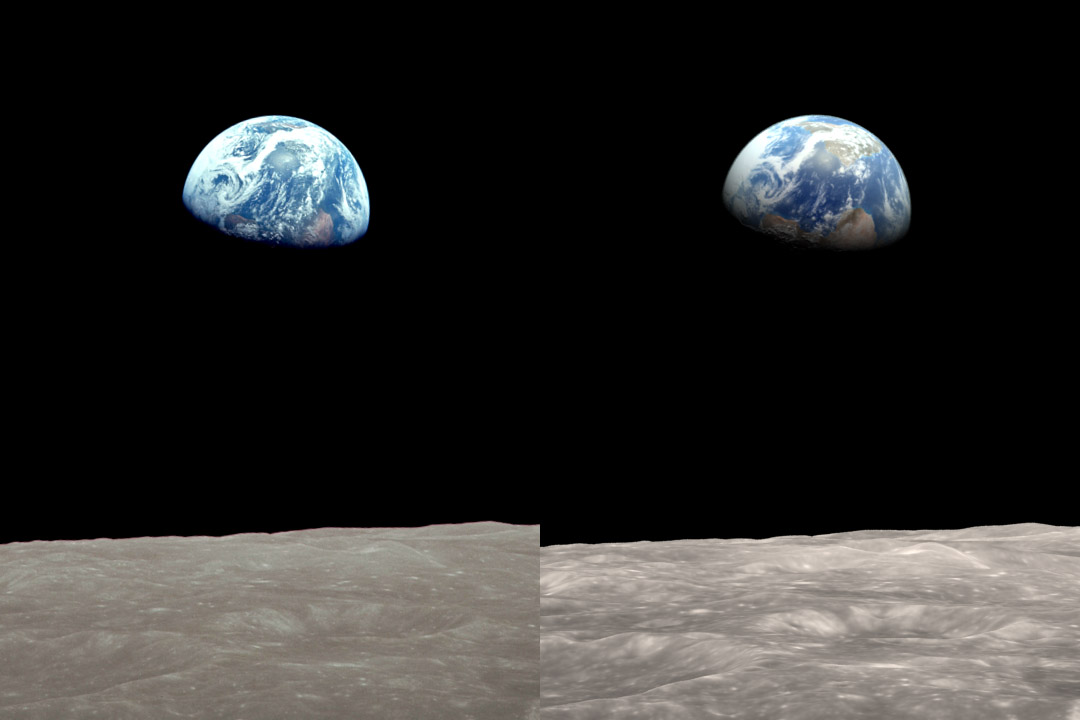

In 2012, I worked on a project to recreate the famous Earthrise photo taken by Apollo 8 astronaut William Anders. My wife had given me a poster of this photo for Christmas, and I thought it’d be a cool way to exhibit LRO data. The photo has the Moon in the foreground with the Earth above the horizon in the background. It was the first time this had been seen by human eyes. I was able to match the computer model of the moon to the original photograph which then told us exactly when the photo was taken, which window it was taken from and who took the picture. I learned from doing this project that these were all open questions, which LRO data helped to answer.

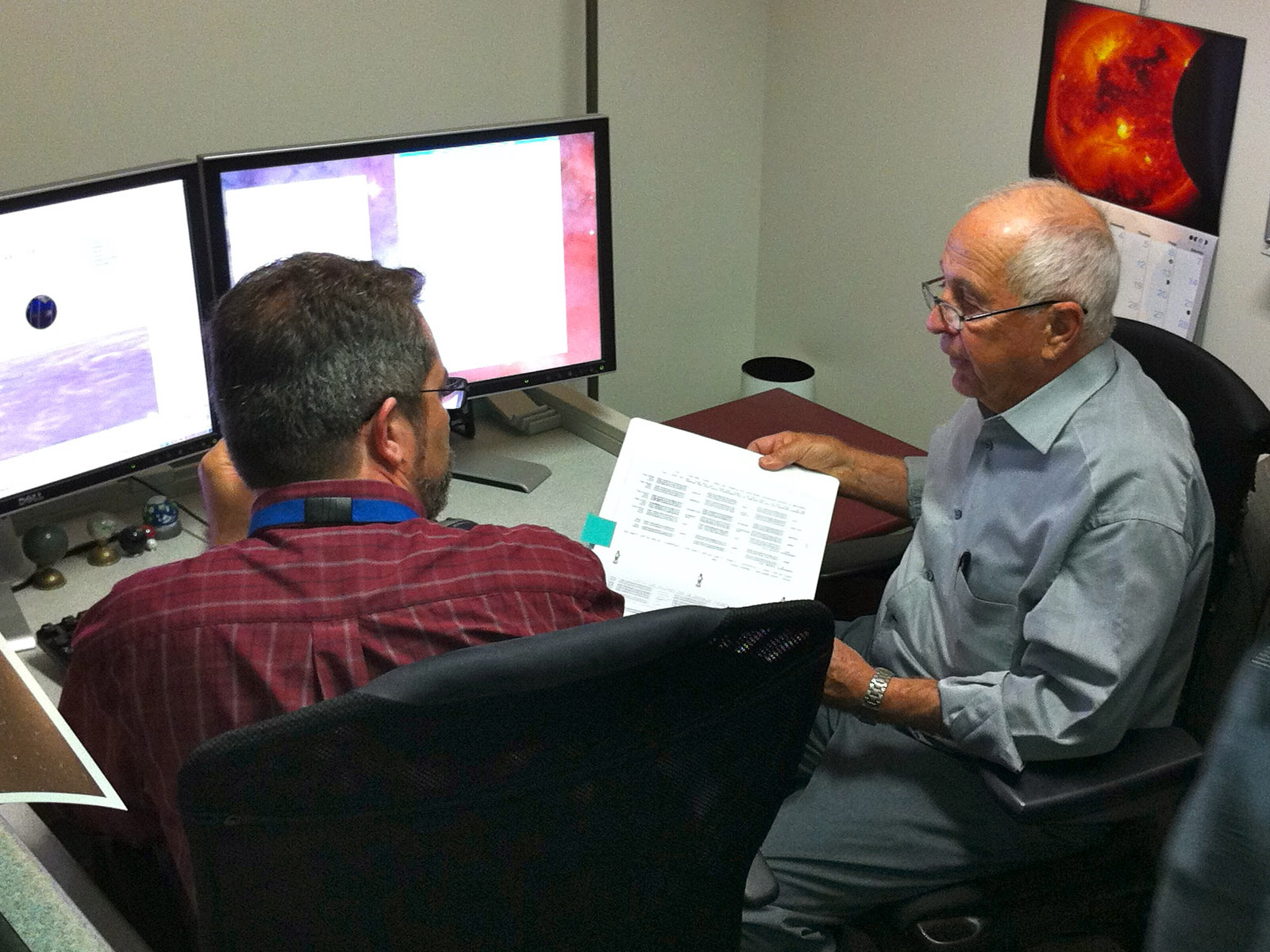

Astronaut Anders came to Goddard to talk to me about it, an amazing and uniquely NASA experience. I wish my dad had been alive to hear about it. He was a big fan of Apollo, something he passed down to me. He collected a bunch of Life and Look magazine special editions that I still have. It was surreal to hear Anders recall the Earthrise moment as I pointed to the computer animation. It seemed to remind him of what it was like in a way he hadn’t seen before.

He gave me an Earthrise poster that he signed, “To Ernie Wright. Your Earthrise was better than mine. Bill Anders, Apollo 8.” This poster is now framed and hanging above my computer.

Since then, I’ve also had the privilege of working with Apollo 17 astronaut Harrison Schmitt, who’s still actively engaged in lunar science. Where else would you get to hang out with two fascinating people who’ve been to the Moon?

Please tell us about your work on Artemis?

I am visualizing the lighting conditions to help the planners understand the unique challenges of that environment, which affects everything they will do on the surface. One of the main challenges about landing at the Moon’s South Pole is the lighting. The Sun is never more than a few degrees above the horizon, so you are always dealing with long shadows. If you are facing the Sun, the Sun is actually in your face, not above you. Visibility is an issue because of the long shadows and glare from the Sun.

All of the Apollo missions landed near the Moon’s equator early in the lunar morning. The lighting was ideal, the surface was not too hot. The astronauts could walk and drive comfortably and see where they were going.

The South Pole is going to be completely different. We are going there because there might be water and other interesting things there including craters in permanent shadow which are some of the coldest spots in the solar system.

Please tell us about your collaboration with the National Philharmonic.

In May 2023, NatPhil is going to have a program called “Cosmic Cycles,” combining NASA imagery with an original composition by Henry Dehlinger. The symphony will have six or seven movements.

My part, working with my LRO producer, is to provide 10 minutes of images of the Moon from LRO. We normally start with the music, then add visuals, but this time we are starting with the images without knowing the music. I pulled out the best images from LRO to send to the composer. The goal is to make the Moon seem like a place, not just a light in the sky.

My mother and her parents were all accomplished musicians and music teachers. I failed to carry on the tradition, but that background still informs what I do. Music and math live right next to each other in our brains. Music is a storytelling medium that conveys meaning and emotion through harmony and rhythm, and you can absolutely incorporate those elements into a visual composition.

Who do you collaborate with?

I work on the public engagement team for LRO. We have a wide range of skills. I’m always really impressed with everyone.

I talk to everybody and translate what the scientists say into something the public will understand. I work with producers who are storytellers and communicators who know how to match the story to music and how to structure the story. I work with people who do social media for the Moon and educational materials.

I feel fortunate to work with so many amazingly creative people at Goddard.

How do you describe what makes a person creative?

Creative people are not afraid to be a little bit strange. They are not afraid of exposing their ideas to criticism, particularly in a collaborative environment. Creative people need to be willing to listen to what other people say about what they do.

Careful observation is an important part of creativity and an important part of the scientific process. Creative people notice things that other people do not. Curiosity is also very important.

Do you have a hobby?

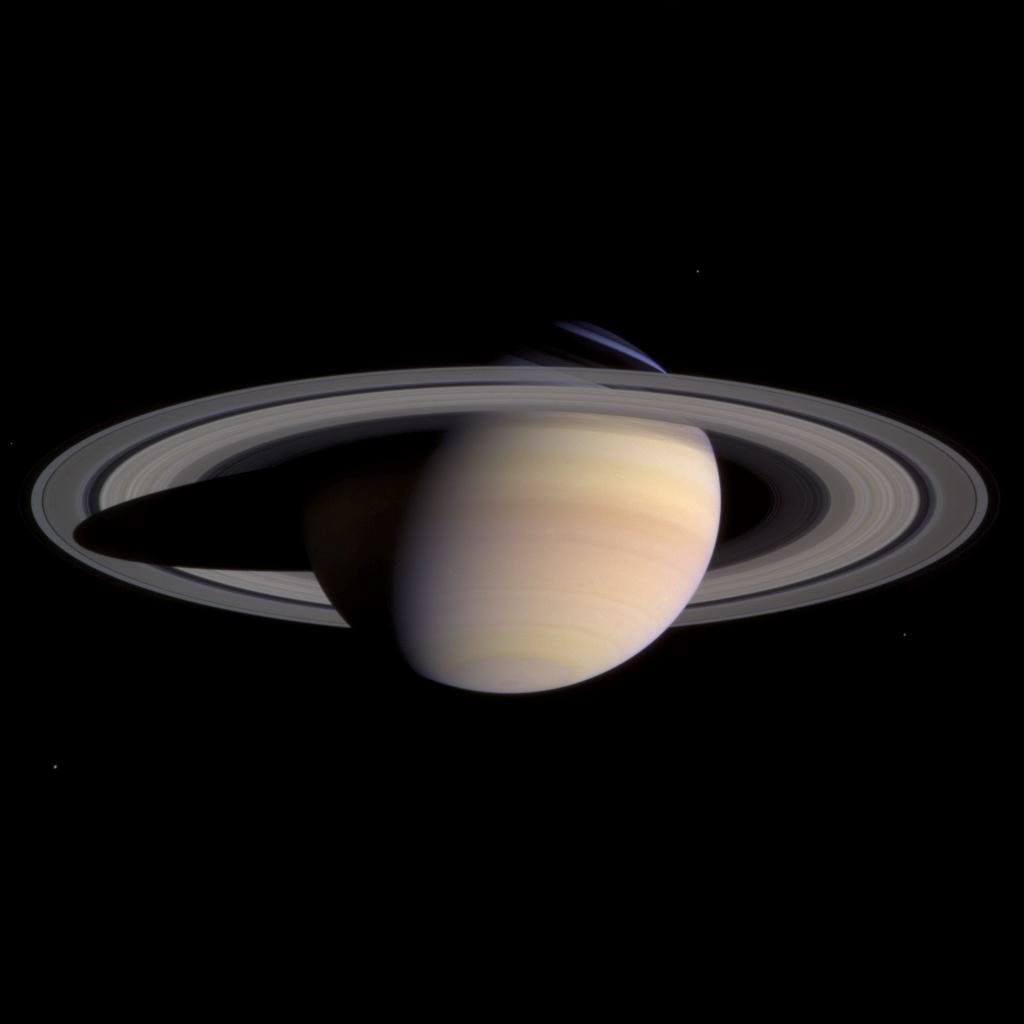

I am an amateur astronomer. I own five telescopes and often go outside when it is dark and clear to look and take photos. Knowing what the Moon looks like has greatly influenced how I render it.

I also enjoy researching family genealogy.

Who is your favorite author?

Martin Gardner, who wrote about the philosophy of science. He also wrote the Mathematical Games column for Scientific American.

Who inspires you?

My wife! I never want her continued faith in me to be unearned. My son’s involvement in musical theater – picking up the family music tradition – played a big role in getting me past my own fears of public speaking, something I started doing for NASA’s 2017 eclipse outreach. And my daughter the published chemist! I’m also inspired by the many Goddard scientists who have the unusual ability to engage the public in NASA science and convey their passion and enthusiasm.

What is your “six-word memoir”? A six-word memoir describes something in just six words.

Luna, a beauty cold and austere.

Conversations With Goddard is a collection of Q&A profiles highlighting the breadth and depth of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center’s talented and diverse workforce. The Conversations have been published twice a month on average since May 2011. Read past editions on Goddard’s “Our People” webpage.