Name: Andrew Sayer

Title: Research Scientist

Organization: Code 613, Climate and Radiation Laboratory, Earth Sciences Division, Sciences Directorate

What do you do and what is most interesting about your role here at Goddard? How do you help support Goddard’s mission?

I am an atmospheric scientist. We have satellites orbiting the Earth with instruments on board. You can think of them as space cameras, recording images of the Earth, except that they can see all the way from ultraviolet to infrared light and not just visible light. Each pixel comes out to something like half a mile across on the ground. My job is to figure out ways to automatically turn these observations, which are like pictures, into useful scientific information.

Most of what I do concerns aerosols such as volcanic ash, dust from desert storms or smoke from wildfires. We convert the satellite images into data showing the amount of aerosol which is important in determining air quality, hazard avoidance, solar energy yields and understanding climate change, among other things.

What is the fundamental question you are trying to answer?

The question my work helps answer is how much aerosol is there in the atmosphere, where does it come from and where does it go, and what is it made of? Typically, aerosols have a lifetime from a few days to a few years, and the amount and composition vary widely from one location to another, so it’s a difficult question to answer.

Which satellites provide you information?

Currently I am working with data from instruments on four different satellites. The instruments are called SeaWiFS, MODIS (there are two of these) and VIIRS. These are all polar-orbiting so they each see any given location on Earth approximately once during the day and approximately once during the night. Most of what we do uses only the daytime measurements, because it works using reflected sunlight. Depending on the latitude, sometimes the satellite sees an area more than once a day.

How do you validate the data?

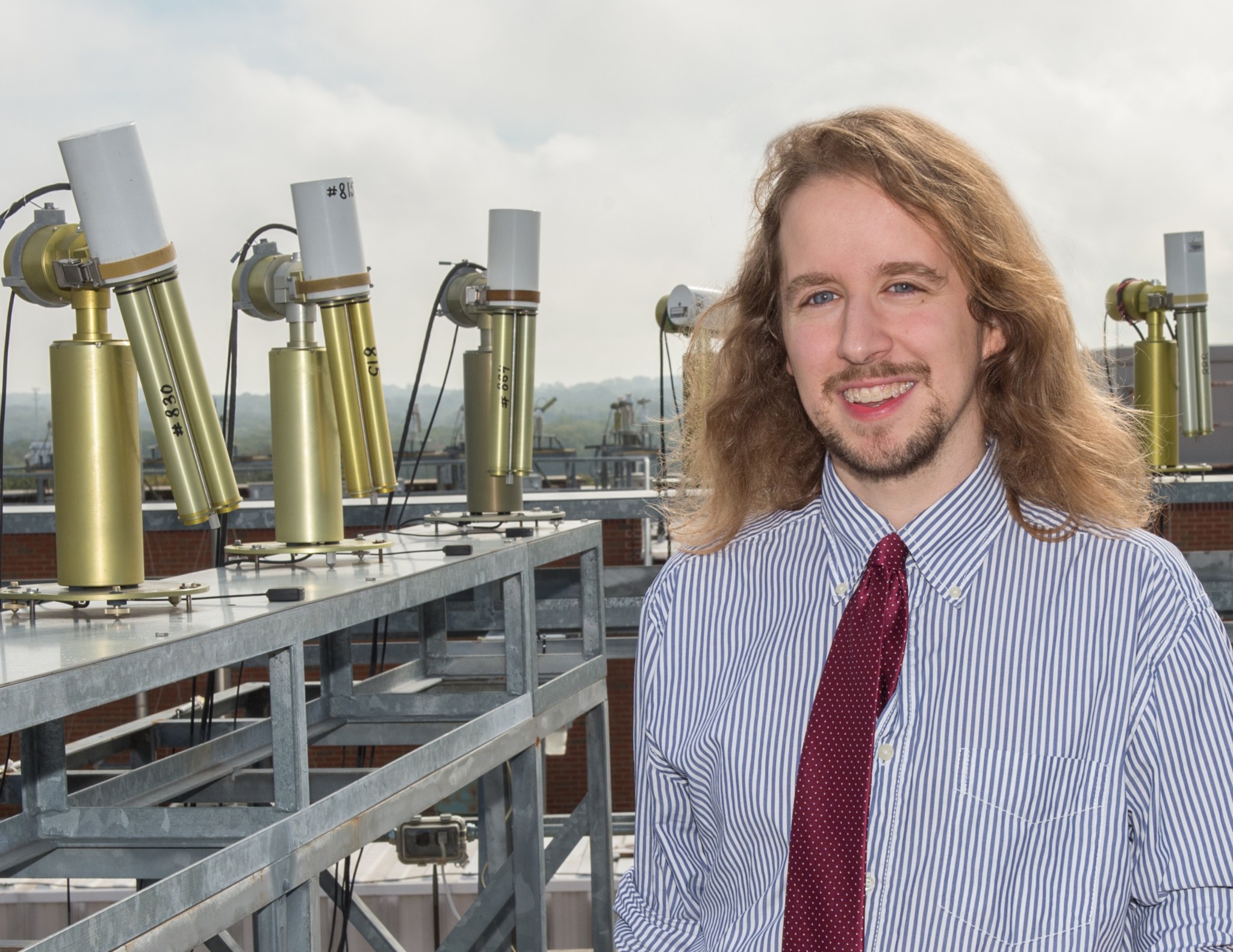

We use ground-based instruments called sun photometers to validate the data from the satellites. The sun photometers provide very accurate information, but only about their specific location. The satellites operate automatically, and have on-board calibration to monitor their stability. The great thing about satellites is that you can see the whole world every day.

NASA has the largest network around the world of about 400 sun photometers. Every so often, the sun photometers are brought in from the field to recalibrate them on top of Building 33 here at NASA Goddard.

What is one of the aerosol events you have worked on that we might know about?

During spring 2010, when I was working in the U.K., the volcano Eyjafjallajökull erupted in Iceland. The ash cloud moved across the European airspace. People needed to figure out the location and amount of ash, to determine if and where it was safe for aircraft to fly. If a plane flies through too much ash, its engines may get damaged or fail.

There are nine Volcanic Ash Advisory Centers (VAACs) globally, one of which is in the United Kingdom. The VAACs use a combination of satellite observations and computer models to try to understand where the ash clouds are and then predict where they will go. Just like a weather forecast, but for ash clouds. As we improve our satellite capabilities, we can help the VAACs improve their predictions.

What is your educational background?

I was born in Scotland and grew up in Scotland and in England. I have a master’s in chemistry from the University of York. After that I was evenly split between going into physics and biology, and ultimately combined my interests, in a sense. I have a doctorate in atmospheric physics from the University of Oxford.

After I got my doctorate, I did a post-doc for another year and a half at Oxford and the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, which is a British national laboratory specializing in physics.

Why did you become a scientist?

When I was about 14, I read Carl Sagan’s book “The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark.” His book outlines what science is and explains the scientific method. It appealed to me because it’s a structured way to go about figuring out how things work. I realized that that I wanted to understand more about the world.

I decided then to become a scientist. I was not yet sure which kind I wanted to be, but I was always interested in the natural world.

I was inspired by my doctorate adviser (professor Don Grainger) who was researching aerosols and clouds using satellite observations. I was interested in how he was using mathematics to help explain something we experience every day.

Everyone sees clouds. I liked the real-world, practical usefulness. When I met him it cemented my decision to pursue a doctorate in physics rather than biology.

How did you get from Oxford to Goddard?

While I was working on my doctorate, I met my Goddard sponsor, Dr. Christina Hsu, an Earth scientist, at a conference in Germany about observing aerosols from space. I was interested in her work at Goddard. Toward the end of my post-doc, I asked her if she had any positions and she helped me come to Goddard. I have been in the same laboratory at Goddard for six years as part of her research group.

Who or what inspires you at Goddard?

I try to attend the monthly Maniac Talks typically given by our senior scientists which are, in effect, a mini biography of where they started and where they are now in their scientific lives. I feel that it really helps to understand where people come from, what they have been through, and their hopes for the future. Knowing these things help increase my profound respect for both their scientific and personal lives including the cultures they came from.

It is not that often that we have time to sit down with someone and listen to their life story and world view. The Maniac Talks allow us to do this.

What lessons or words of wisdom have you passed along to your summer interns?

Last summer, I was in charge of three high-school interns. What I tried to show them is that science is not about having the answers, it is more about asking the right questions and knowing how to figure out the answers.

We really benefit from having people from different backgrounds with different expertise thinking about problems in different ways. A lot of what we do is interdisciplinary.

We don’t have any true Renaissance men any more. No one person can figure out everything on their own. In science, there simply is not enough time to do everything with all the data. We need each other.

Is there something surprising about you that people do not generally know?

I am a member of a classical band called the Arlington Concert Band. I play tenor saxophone, which I have played since I was 11. We play around half a dozen free concerts in the Arlington area throughout the year, especially in schools. Our band has about 50 musicians, from high school students through retired people. It is a great way to meet people in the community and hopefully encourage school children to always keep music a part of their lives.

Who is your science hero?

If pressed, I’d probably say Carl Sagan because he was the initial force that set me on the path to becoming a scientist. My parents aren’t scientists, but always fostered my curiosity and creativity growing up, so they deserve some credit too! It’s hard to single out because I admire so many different people.

What do you miss most about Scotland?

I miss the rolling hills, fields and woodlands. Acadia National Park in Maine and Nova Scotia (Canada), are the closest I have come to finding the same ambiance in North America. I love a lot of the terrain in the U.S.; there’s so much to see. But I miss what I grew up with.

Have you ever met a member of the royal family?

When I was at Oxford, I was in Trinity College, which then celebrated its 450th anniversary. Prince Charles came to commemorate the occasion. I was one of a few students my college invited to meet Prince Charles and tell him about what we did. I even shook his hand.

Beforehand the group of us were given a short briefing to go through the etiquette of the appropriate way to address him (“Your Royal Highness”), as meeting royalty was a new experience for us!

By Elizabeth M. Jarrell

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

Conversations With Goddard is a collection of Q&A profiles highlighting the breadth and depth of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center’s talented and diverse workforce. The Conversations have been published twice a month on average since May 2011. Read past editions on Goddard’s “Our People” webpage.