New analyses of NASA airborne radar data collected in 2012 reveal the radar detected indications of a huge sinkhole before it collapsed and forced evacuations near Bayou Corne, La. that year.

The findings suggest such radar data, if collected routinely from airborne systems or satellites, could at least in some cases foresee sinkholes before they happen, decreasing danger to people and property.

Sinkholes are depressions in the ground formed when Earth surface layers collapse into caverns below. They usually form without warning. The data were collected as part of an ongoing NASA campaign to monitor sinking of the ground along the Louisiana Gulf Coast.

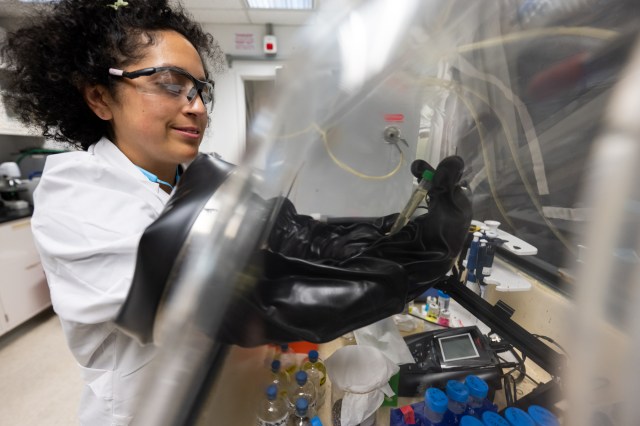

Researchers Cathleen Jones and Ron Blom of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, Calif., analyzed interferometric synthetic aperture radar (InSAR) imagery of the area acquired during flights of the agency’s Uninhabited Airborne Vehicle Synthetic Aperture Radar (UAVSAR), which uses a C-20A jet, in June 2011 and July 2012. InSAR detects and measures very subtle deformations in Earth’s surface.

Their analyses showed the ground surface layer deformed significantly at least a month before the collapse, moving mostly horizontally up to 10.2 inches (260 millimeters) toward where the sinkhole would later form. These precursory surface movements covered a much larger area — about 1,640 by 1,640 feet, (500 by 500 meters) — than that of the initial sinkhole, which measured about 2 acres (1 hectare).

Results of the study are published in the February issue of the journal Geology.

“While horizontal surface deformations had not previously been considered a signature of sinkholes, the new study shows they can precede sinkhole formation well in advance,” said Jones. “This kind of movement may be more common than previously thought, particularly in areas with loose soil near the surface.”

The Bayou Corne sinkhole formed unexpectedly Aug. 3, 2012, after weeks of minor earthquakes and bubbling natural gas that provoked community concern. It was caused by the collapse of a sidewall of an underground storage cavity connected to a nearby well operated by Texas Brine Company and owned by Occidental Petroleum. On-site investigation revealed the storage cavity, located more than 3,000 feet (914 meters) underground, had been mined closer to the edge of the subterranean Napoleonville salt dome than thought. The sinkhole, which filled with slurry –a fluid mixture of water and pulverized solids– has gradually expanded and now measures about 25 acres (10.1 hectares) and is at least 750 feet (229 meters) deep. It is still growing.

“Our work shows radar remote sensing could offer a monitoring technique for identifying at least some sinkholes before their surface collapse, and could be of particular use to the petroleum industry for monitoring operations in salt domes,” said Blom. “Salt domes are dome-shaped structures in sedimentary rocks that form where large masses of salt are forced upward. By measuring strain on Earth’s surface, this capability can reduce risks and provide quantitative information that can be used to predict a sinkhole’s size and growth rate.”

Typically, sinkholes have no natural external surface drainage, and they form through natural processes and human activities. They occur in regions of “karst” terrain where the rock below the surface can be dissolved by groundwater, most commonly in areas with limestone or other carbonate rocks, gypsum, or salt beds. When the rocks dissolve, they form spaces and caverns underground. Sinkholes vary in size from a few feet across to hundreds of acres, and some can be very deep. They are common hazards worldwide and are found in all regions of the United States, with Florida, Missouri, Texas, Alabama, Kentucky, Tennessee and Pennsylvania reporting the most sinkhole damage. While sinkhole deaths are rare, in February 2013 a man in Tampa, Fla., was killed when his house was swallowed by a sinkhole.

The human-produced Bayou Corne sinkhole occurred in an area not prone to sinkholes. The Gulf Coast of Louisiana and eastern Texas sits on an ancient ocean floor with salt layers that form domes as the lower-density salt rises. The Napoleonville salt dome underneath Bayou Corne extends to within 690 feet (210 meters) of the surface. Various companies mine caverns in the dome by dissolving the salt to obtain brine and subsequently store fuels and salt water in the caverns.

Jones and Blom say continued UAVSAR monitoring of the area as recently as October 2013 has shown a widening area of deformation, with the potential to affect other nearby storage cavities located near the salt dome’s outer wall. Because the Bayou Corne sinkhole is now filled with water, it is harder to measure deformation of the area using InSAR. However, if the deformation extends far past the sinkhole boundaries, InSAR could continue to track surface movement caused by changes below the surface.

Continued growth of the sinkhole threatens the community and Highway 70, so there is a pressing need for reliable estimates of how fast it may expand and how big it may eventually get.

“This kind of data could be of great value in determining the direction in which the sinkhole is likely to expand,” said Jones. “At Bayou Corne, it appears that material is continuing to flow into the huge cavern that is undergoing collapse.”

Blom says there are no immediate plans to fly UAVSAR over sinkhole-prone areas.

“You could spend a lot of time flying and processing data without capturing a sinkhole,” he said. “Our discovery at Bayou Corne was really serendipitous. But it does demonstrate one of the expected benefits of an InSAR satellite that would image wide areas frequently.

“Every year, unexpected ground motions from sinkholes, landslides and levee failures cost millions of dollars and many lives,” said Jones. “When there is small movement prior to a catastrophic collapse, such subtle precursory clues can be detected by InSAR.”

NASA monitors Earth’s vital signs from land, air and space with a fleet of satellites and ambitious airborne and ground-based observation campaigns. NASA develops new ways to observe and study Earth’s interconnected natural systems with long-term data records and computer analysis tools to better see how our planet is changing. The agency shares this unique knowledge with the global community and works with institutions in the United States and around the world that contribute to understanding and protecting our home planet.

For more information about UAVSAR, visit:

http://uavsar.jpl.nasa.gov/

For more information about NASA’s Earth science activities in 2014, visit:

https://www.nasa.gov/earthrightnow

For information on the latest NASA Earth science findings, visit:

https://www.nasa.gov/earth

-end-

J.D. Harrington

Headquarters, Washington

202-358-5241

j.d.harrington@nasa.gov

Alan Buis

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

818-354-0474

alan.buis@jpl.nasa.gov