With a merging of technology and tears, the final chapter in the 30-year history of space shuttle flights has been written. For all who have worked to send these first-of-a-kind engineering marvels to space and return them to Earth, all who have flown aboard them, and all who have simply watched with awe and pride as they flew, space shuttle Atlantis’ STS-135 mission was an emotional end of an era.

It was a hot July day on Florida’s Space Coast as nearly a million spectators gathered along the beaches, rivers and causeways to watch history in the making. The weather forecast was a daunting 70 percent “no-go” to start the day, yet the countdown proceeded smoothly.

Just as expectations peaked and launch looked imminent, a last-minute glitch held the clock at T-31 seconds. The issue — whether the gaseous oxygen vent arm had fully retracted — was quickly resolved by the experienced team inside the Launch Control Center at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, and the clock began counting down the final seconds.

Down to the wire, with less than a minute left in the day’s launch window, the three main engines roared to life and the twin solid rocket boosters thundered. Atlantis rose from the launch pad on a plume of fire and parted the high clouds on its way to the International Space Station and to its place in history. The 11:29 a.m. EDT liftoff on July 8, 2011, marked the last time a space shuttle would climb from Kennedy’s seaside launch complex to soar toward the heavens.

“The space shuttle spreads its wings one final time for the start of a sentimental journey into history,” said Ascent Commentator Rob Navias. As the shuttle achieved orbit, Navias added, “For the last time, the space shuttle’s main engines have fallen silent as the shuttle slips into the final chapter of a storied 30-year adventure.”

The crew of four veteran astronauts aboard Atlantis — Commander Chris Ferguson, Pilot Doug Hurley, and Mission Specialists Sandy Magnus and Rex Walheim — set off on the STS-135 mission to deliver a stockpile of supplies and parts to the space station.

“We’re really looking forward to a great mission. This is a very critical mission for station resupply,” said Space Shuttle Program Launch Integration Manager and chairman of the preflight Mission Management Team Mike Moses as he spoke at the post-launch news conference. “I think the shuttle program is ending exactly as it should. We’ve built the International Space Station, we’re stocking it up for the future, and ready to hand it off — and we finish really, really strong.”

The crew got down to business after reaching orbit as they headed for a rendezvous and docking with the space station two days after launch. One of the main tasks before meeting up with the station was getting a close look at Atlantis’ heat shield to verify that it hadn’t sustained any damage during the climb to orbit. Mission Control in Houston gave them a “thumbs up” on the inspection results a few days later.

Once Atlantis caught up to the space station, Ferguson executed a backflip about 600 feet below to enable station crew members to photograph the shuttle’s heat shield. The photos were evaluated by experts on the ground to look for any damage and none was found.

With that complete, Atlantis began its final approach to the station from about eight miles and successfully docked two days after launch. The station crew greeted Atlantis with the ceremonial ringing of the station’s bell, welcoming a visiting space shuttle for the final time.

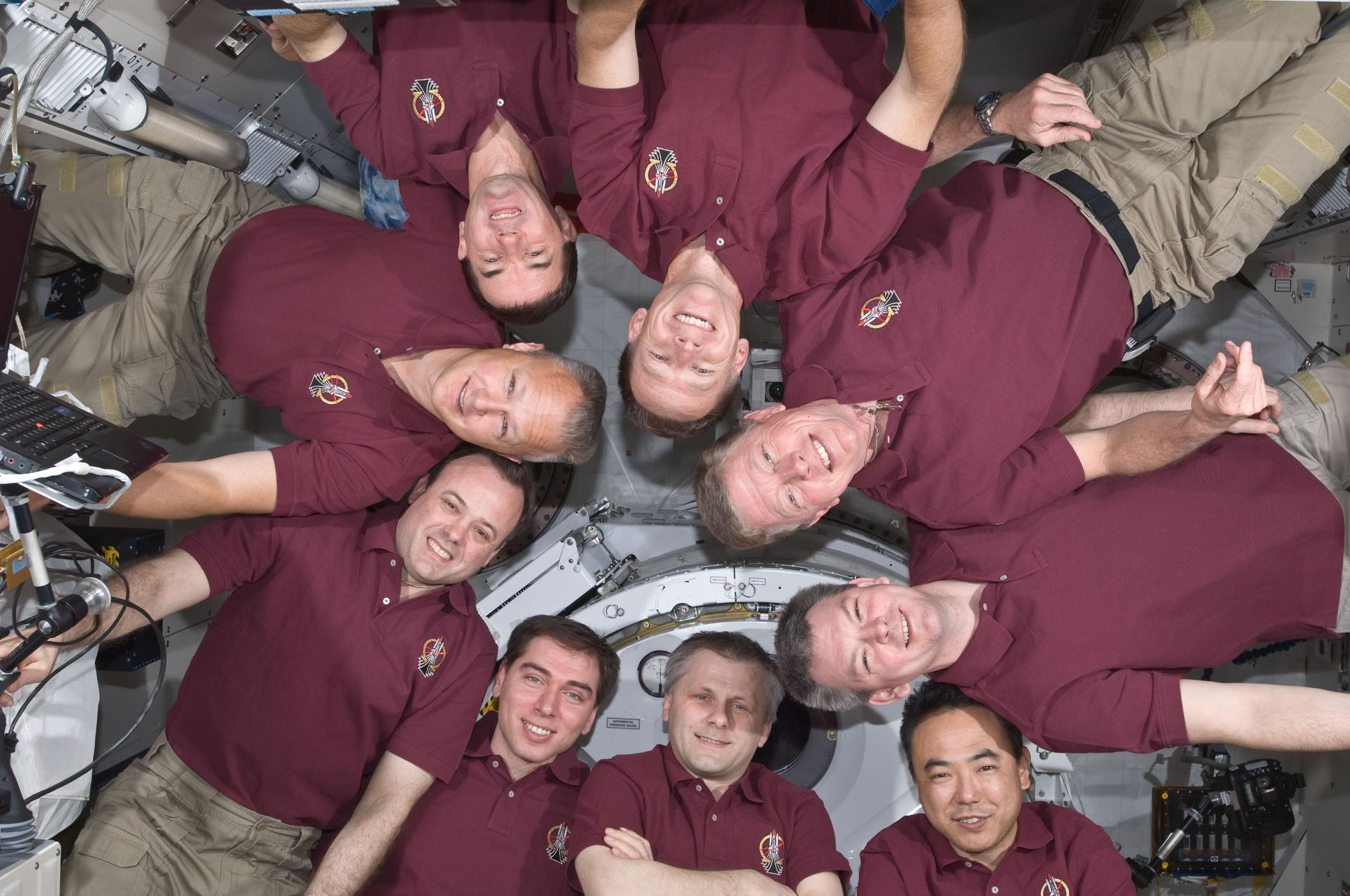

After docking, the hatches separating the two spacecraft were opened. Waiting aboard the station to greet the Atlantis astronauts were Expedition 28 Commander Andrey Borisenko and Flight Engineers Alexander Samokutyaev, Ron Garan, Sergei Volkov, Mike Fossum and Satoshi Furukawa.

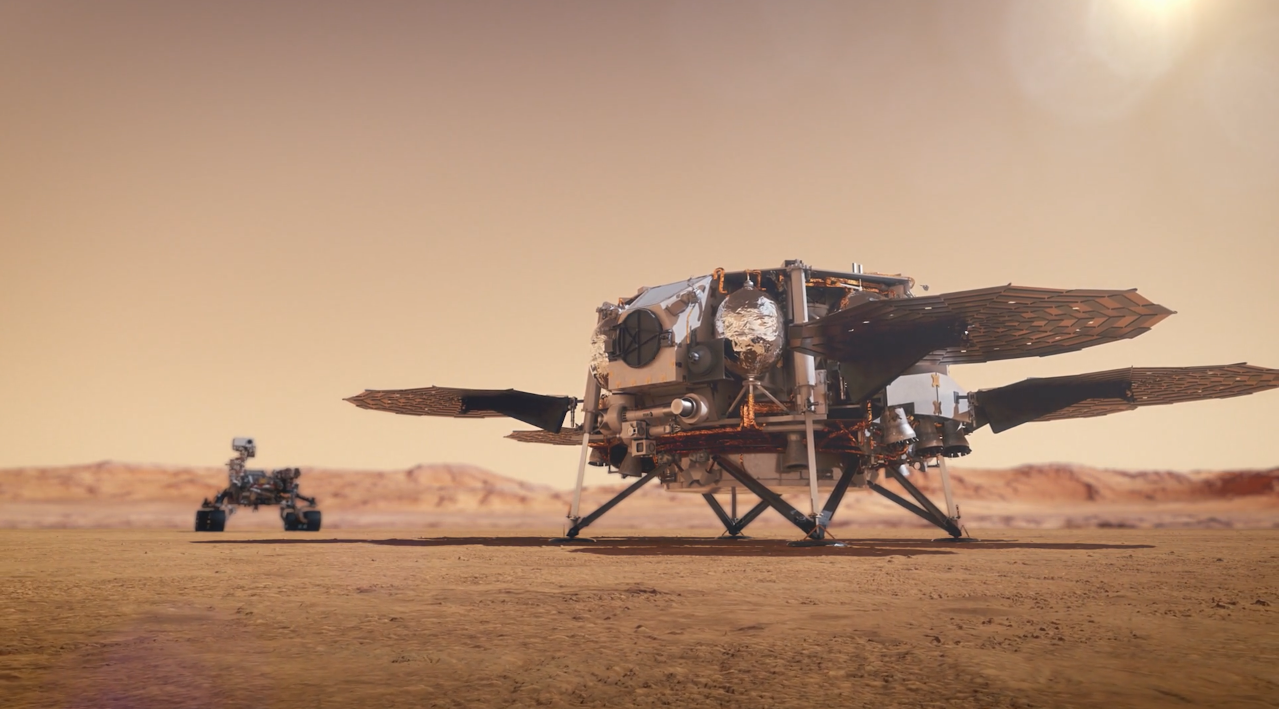

Getting down to the main objective of their mission, Magnus and Hurley took the controls of the space station’s robotic arm and removed the Raffaello multipurpose logistics module from the shuttle’s cargo bay and temporarily installed it on the Earth-facing port of the station’s Harmony node.

While the bulk of the work on many shuttle missions has revolved around spacewalks, this mission’s main focus was inside. Over the course of the more than eight days Atlantis spent docked to the station, both crews spent much of their time unloading more than 9,400 pounds of supplies and equipment from Raffaello, plus the additional 2,200 pounds stowed on the shuttle’s middeck. For the return trip to Earth, Raffaello was with filled with 5,700 pounds of equipment and discards no longer needed on the station.

Magnus, a former space station resident, served as the mission’s load master in charge of the massive moving operations. While moving objects in the weightlessness of space might sound easy, the mass of the cargo bags require effort to put them in motion, change their direction and stop their motion. The crew was given some extra time to complete the extensive transfer when the mission was extended by one day.

Two days after Atlantis arrived at the station, the only spacewalk during the mission was performed not by shuttle astronauts, but by two station residents who three years earlier had collaborated on three spacewalks when they were STS-124 shuttle crewmates.

Now as Expedition 28 flight engineers, Fossum and Garan were paired again as they spent six hours and 31 minutes working outside the station. Choreographed from inside Atlantis by Walheim, Hurley and Magnus operated the station’s 58-foot-long robotic arm to maneuver the spacewalkers around the exterior of the joined spacecraft.

Among the spacewalkers’ tasks was retrieving the station’s failed 1,400-pound cooling system pump module that was replaced after it stopped working in 2010. Moving the pump from its temporary storage location, it was packed it in the shuttle’s cargo bay. Returning the pump to Earth will allow engineers to look into what caused its failure and then refurbish it for use as a spare in the future.

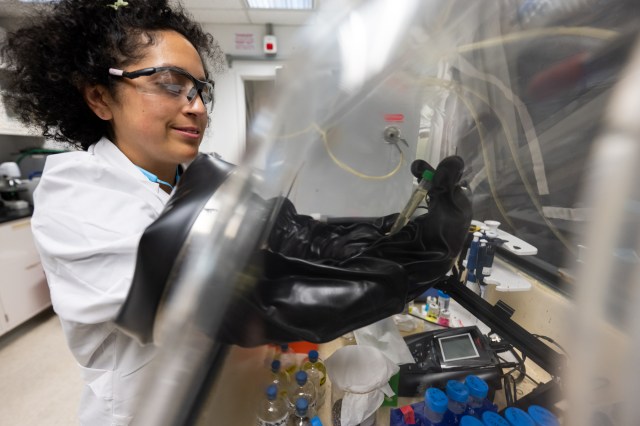

The pair installed the Robotic Refueling Mission experiment, which will test whether remote-controlled robots can perform satellite refueling tasks in orbit, using commands sent from controllers on Earth. The capability is expected to reduce costs and risks, and lay the foundation for future robotic servicing missions.

Another experiment deployed during the spacewalk was the Optical Reflector Materials Experiment, a portion of the Materials International Space Station Experiment 8 that was installed on the External Logistics Carrier 2 during STS-134.

With the completion of several other outside maintenance tasks, the pair ended this 249th spacewalk by U.S. astronauts, which marked the seventh for Fossum and the fourth for Garan. It was the 160th spacewalk in support of station assembly and maintenance.

One week into Atlantis’ mission, President Barack Obama radioed the combined shuttle and station crews to help mark the final shuttle flight. The President told them, “We’re all watching as the 10 of you work together as a team,” adding, “Your example means so much not just to your fellow Americans, but also your fellow citizens on Earth. The space program has always embodied our sense of adventure and explorations and courage.”

He also thanked those who have supported the Space Shuttle Program during the past 30 years of flight, and all the men and women of NASA who helped the country lead the space age.

During the mission, the crew took time out from their duties to speak with media and students on the ground. They also tackled some unscheduled repair work, fixing both a broken door latch on Atlantis’ middeck floor and getting the shuttle’s general purpose computer 4 back online after reloading its software.

Ferguson presented the station’s crew a U.S. flag flown on the first space shuttle mission, STS-1. The flag will remain displayed onboard the station until the next crew launched from the U.S. retrieves it for return to Earth so that it can be carried by the first crew launched from the U.S. on a journey of exploration beyond Earth orbit.

With the last of the mission’s work at the station complete, shuttle and station crews parted company for the last time.

As Atlantis departed, Ferguson reflected on the view of the completed station, saying, “When a generation accomplishes a great thing, it’s got a right to stand back and for just a moment admire and take pride in its work.” He added, “As the ISS now enters the era of utilization we’ll never forget the role the space shuttle played in its creation. Like a proud parent, we anticipate great things to follow from the men and women who build, operate and live there. From this unique vantage point we can see a great thing has been accomplished. Farewell ISS. Make us proud.”

After slowly backing away from the station, Atlantis began a unique fly-around. Hurley moved the shuttle 600 feet in front of the complex and paused while the orbiting laboratory changed its orientation by rotating 90 degrees to the right. Atlantis began a half loop around the station, giving Walheim and Magnus the opportunity to snap digital pictures of the station from angles never photographed before during a fly-around. The images will be evaluated by experts on the ground to get additional information on the condition of the station’s exterior. After completing the half loop, two separation burns propelled the shuttle away from the station.

Flying alone in space once more, the astronauts finished up their work during last few days aboard Atlantis. They deployed a small, eight-pound technology demonstration satellite from a canister in the shuttle cargo bay. The satellite, called PicoSat, will relay data back to investigators regarding the performance of its solar cells. PicoSat became the 180th and last payload deployed from a space shuttle.

In preparation for landing, the astronauts used the 50-foot-long Orbiter Boom Sensor System to conduct a high-fidelity, three-dimensional scan of Atlantis’ wing leading edges and nose cap and received the “all clear” from mission managers. The crew also checked out the shuttle’s flight control surfaces, hot fired its reaction control system jets and rehearsed landing on a laptop computer.

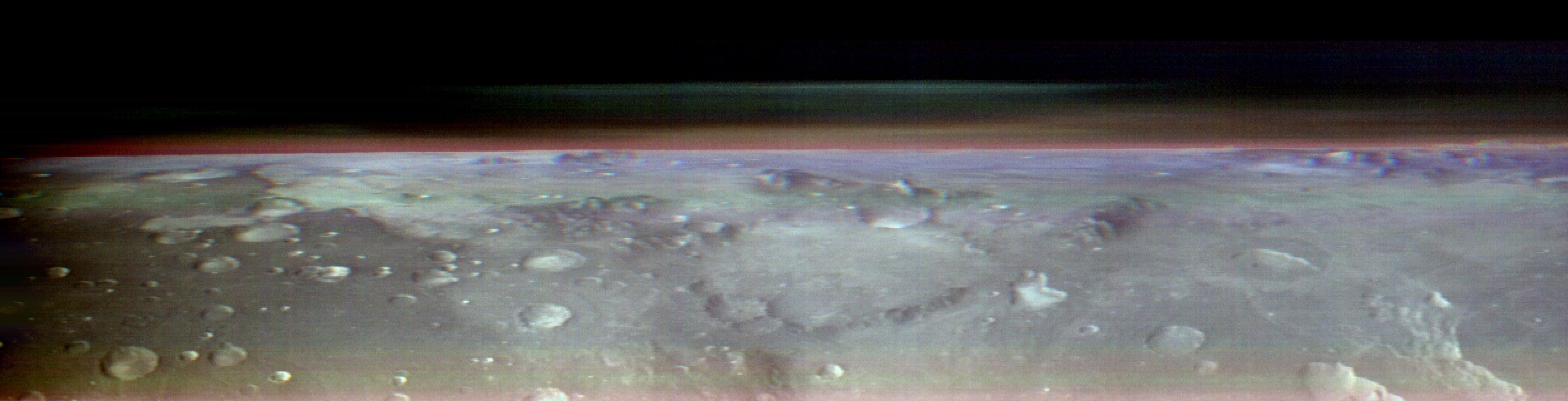

Weather on landing day proved more predictable than it was for launch, and Mission Control in Houston gave the STS-135 astronauts the “go” for a deorbit burn that would bring them home on their 200th orbit of Earth. At 5:57 a.m. on July 21, space shuttle Atlantis dropped out of the predawn darkness and landed at Kennedy’s Shuttle Landing Facility Runway 15. Caught in the last seconds by the brilliant xenon lights, a space shuttle rolled to a stop for the final time.

“Although we got to take the ride,” said Commander Chris Ferguson on behalf of his crew as they stood on the runway, “we sure hope that everybody who has ever worked on, or touched, or looked at, or envied or admired a space shuttle was able to take just a little part of the journey with us.”

With that, the flying days of the most amazing and complicated machine ever built came to an end. But its legacy will live on as the quest to explore space continues.

More about STS-135:

› STS-135 Mission by the Numbers

› Wake Up Calls

› Crew Poster (2.35MB PDF)

› Mission Poster (2.23MB PDF)

Cheryl L. Mansfield

NASA’s John F. Kennedy Space Center