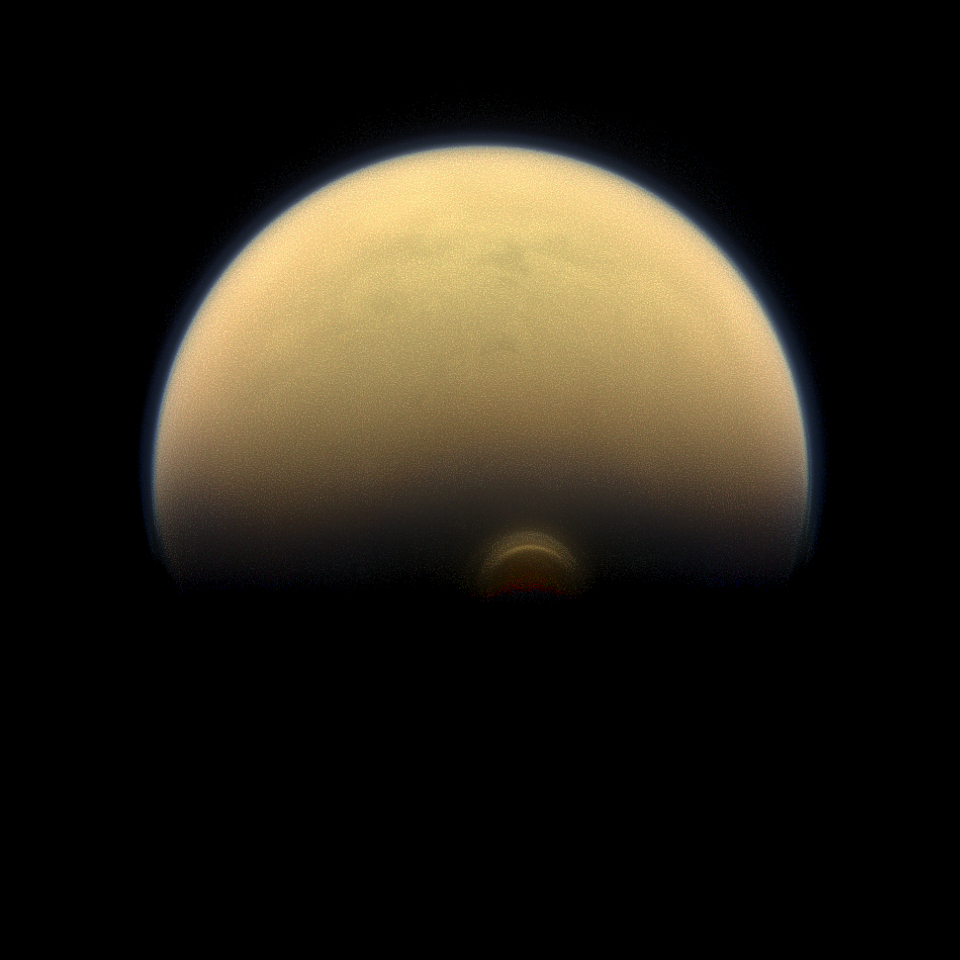

New observations made near the south pole of Titan by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft add to the evidence that winter comes in like a lion on this moon of Saturn.

Scientists have detected a monstrous new cloud of frozen compounds in the moon’s low- to mid-stratosphere – a stable atmospheric region above the troposphere, or active weather layer.

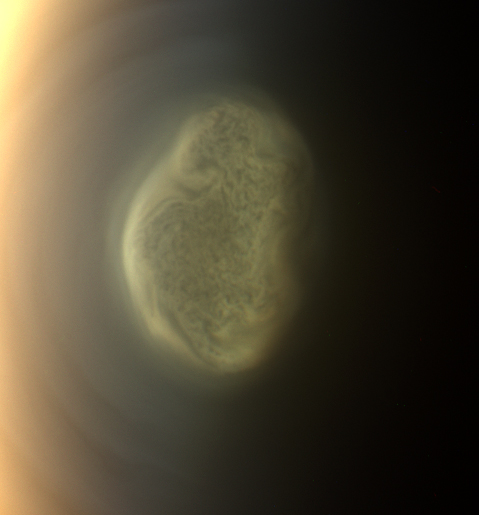

Cassini’s camera had already imaged an impressive cloud hovering over Titan’s south pole at an altitude of about 186 miles (300 kilometers). However, that cloud, first seen in 2012, turned out to be just the tip of the iceberg. A much more massive ice cloud system has now been found lower in the stratosphere, peaking at an altitude of about 124 miles (200 kilometers).

The new cloud was detected by Cassini’s infrared instrument – the Composite Infrared Spectrometer, or CIRS – which obtains profiles of the atmosphere at invisible thermal wavelengths. The cloud has a low density, similar to Earth’s fog but likely flat on top.

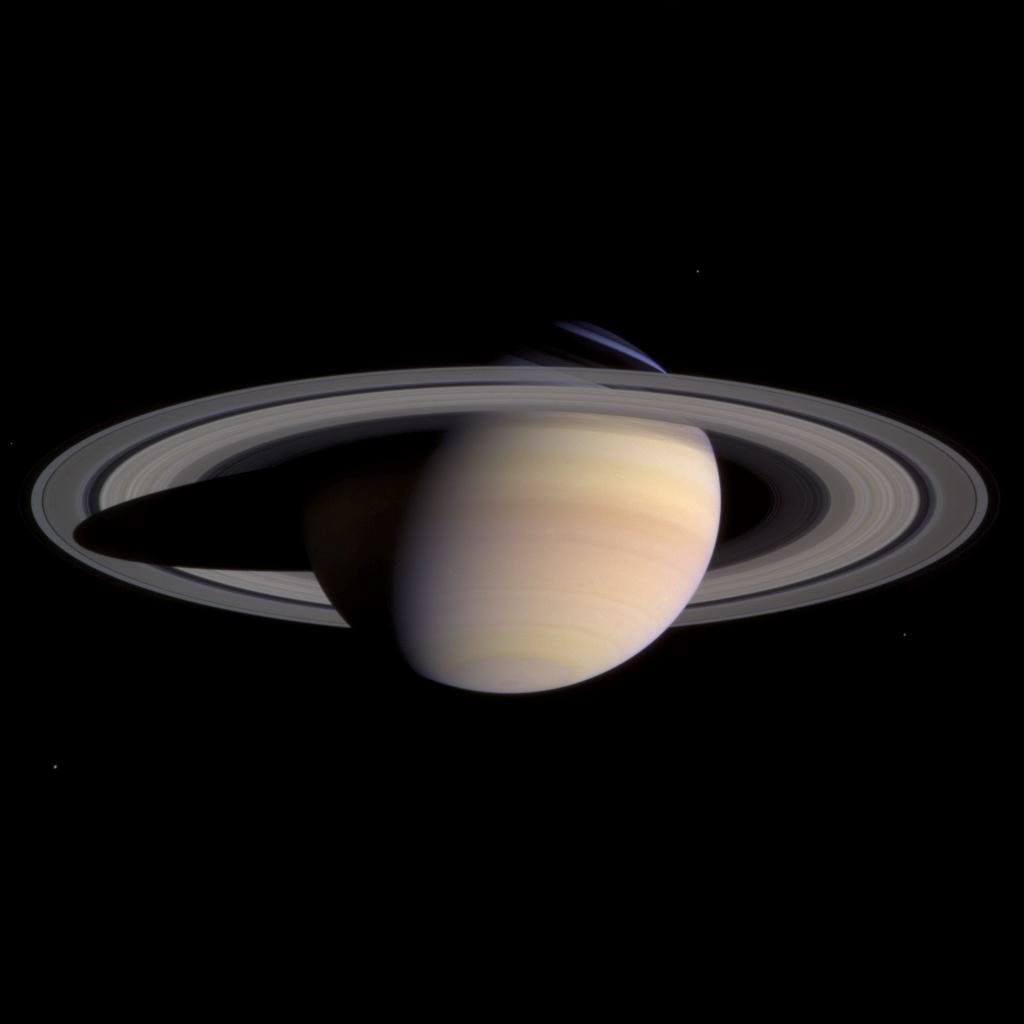

For the past few years, Cassini has been catching glimpses of the transition from fall to winter at Titan’s south pole – the first time any spacecraft has seen the onset of a Titan winter. Because each Titan season lasts about 7-1/2 years on Earth’s calendar, the south pole will still be enveloped in winter when the Cassini mission ends in 2017.

“When we looked at the infrared data, this ice cloud stood out like nothing we’ve ever seen before,” said Carrie Anderson of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “It practically smacked us in the face.”

Anderson is presenting the findings at the annual Meeting of the Division of Planetary Sciences of the American Astronomical Society at National Harbor, Maryland, on Nov. 11.

The ice clouds at Titan’s pole don’t form in the same way as Earth’s familiar rain clouds.

For rain clouds, water evaporates from the surface and encounters cooler temperatures as it rises through the troposphere. Clouds form when the water vapor reaches an altitude where the combination of temperature and air pressure is right for condensation. The methane clouds in Titan’s troposphere form in a similar way.

However, Titan’s polar clouds form higher in the atmosphere by a different process. Circulation in the atmosphere transports gases from the pole in the warm hemisphere to the pole in the cold hemisphere. At the cold pole, the warm air sinks, almost like water draining out of a bathtub, in a process known as subsidence.

The sinking gases – a mixture of smog-like hydrocarbons and nitrogen-bearing chemicals called nitriles – encounter colder and colder temperatures on the way down. Different gases will condense at different temperatures, resulting in a layering of clouds over a range of altitudes.

Cassini arrived at Saturn in 2004 – mid-winter at Titan’s north pole. As the north pole has been transitioning into springtime, the ice clouds there have been disappearing. Meanwhile, new clouds have been forming at the south pole. The build-up of these southern clouds indicates that the direction of Titan’s global circulation is changing.

“Titan’s seasonal changes continue to excite and surprise,” said Scott Edgington, Cassini deputy project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California. “Cassini, with its very capable suite of instruments, will continue to periodically study how changes occur on Titan until its Solstice mission ends in 2017.”

The size, altitude and composition of the polar ice clouds help scientists understand the nature and severity of Titan’s winter. From the ice cloud seen earlier by Cassini’s camera, scientists determined that temperatures at the south pole must get down to at least -238 degrees Fahrenheit (-150 degrees Celsius).

The new cloud was found in the lower stratosphere, where temperatures are even colder. The ice particles are made up of a variety of compounds containing hydrogen, carbon and nitrogen.

Anderson and her colleagues had found the same signature in CIRS data from the north pole, but in that case, the signal was much weaker. The very strong signature of the south polar cloud supports the idea that the onset of winter is much harsher than the end.

“The opportunity to see the early stages of winter on Titan is very exciting,” said Robert Samuelson, a Goddard researcher working with Anderson. “Everything we are finding at the south pole tells us that the onset of southern winter is much more severe than the late stages of Titan’s northern winter.”

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, ESA (European Space Agency) and the Italian Space Agency. JPL manages the mission for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. The CIRS team is based at Goddard.

For more information about Cassini, visit:

By: Elizabeth Zubritsky

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

JPL Media Contact:

Preston Dyches

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

818-354-7013

preston.dyches@jpl.nasa.gov