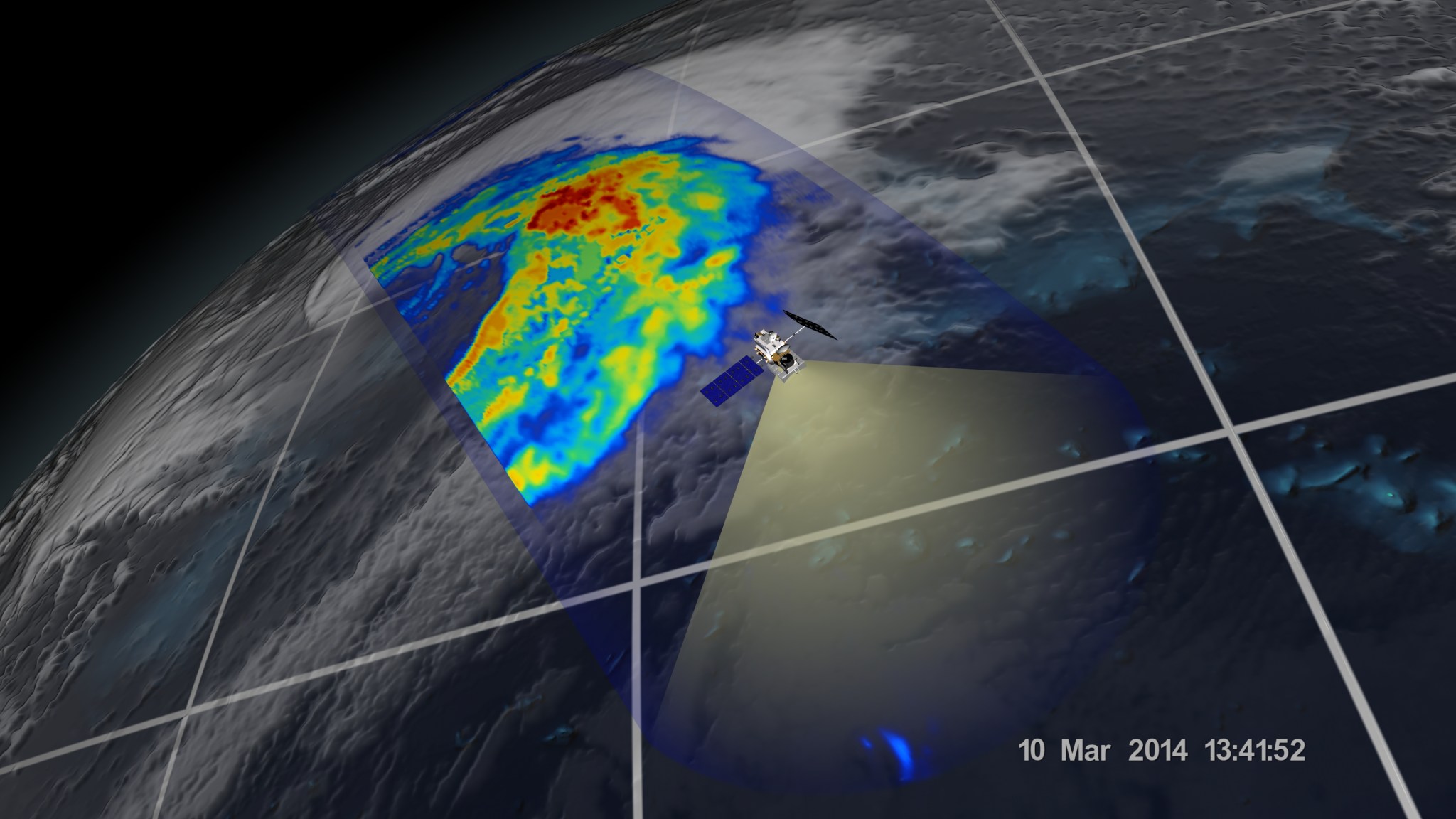

NASA and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) have released the first images captured by their newest Earth-observing satellite, the Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) Core Observatory, which launched into space Feb. 27.

Wallops plays a key role in supporting GPM ground validation studies through remote campaigns in various weather conditions and terrains as well as through its precipitation facility using radars and rain/snow gauges. The ground validation activity supports scientists in improving forecasting models using GPM data and also verifies data from the GPM Core Observatory.

In addition, Wallops engineers and technicians designed and developed the core components of the spacecraft’s high gain antenna system, key for transferring data from and communications with the satellite.

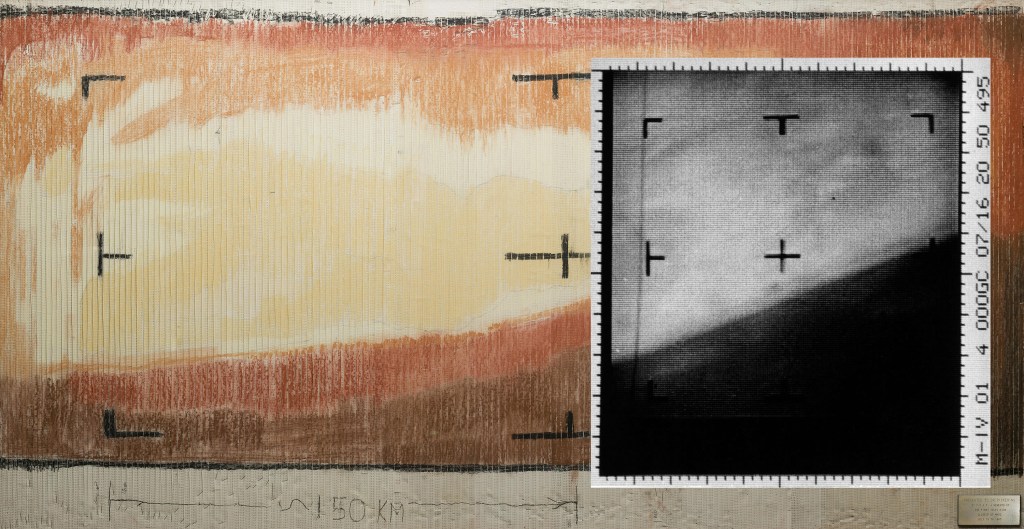

The images received show precipitation falling inside a March 10 cyclone over the northwest Pacific Ocean, approximately 1,000 miles east of Japan. The data were collected by the GPM Core Observatory’s two instruments: JAXA’s Dual-frequency Precipitation Radar (DPR), which imaged a three-dimensional cross-section of the storm; and, NASA’s GPM Microwave Imager (GMI), which observed precipitation across a broad swath.

“It was really exciting to see this high-quality GPM data for the first time,” said GPM project scientist Gail Skofronick-Jackson at NASA’s Goddard Spaceflight Center in Greenbelt, Md. “I knew we had entered a new era in measuring precipitation from space. We now can measure global precipitation of all types, from light drizzle to heavy downpours to falling snow.”

The satellite’s capabilities are apparent in the first images of the cyclone. Cyclones such as the one imaged — an extra-tropical cyclone — occur when masses of warm air collide with masses of cold air north or south of the tropics. These storm systems can produce rain, snow, ice, high winds, and other severe weather. In these first images, the warm front ahead of the cyclone shows a broad area of precipitation — in this case, rain — with a narrower band of precipitation associated with the cold front trailing to the southwest. Snow is seen falling in the northern reaches of the storm.

The GMI instrument has 13 channels that measure natural energy radiated by Earth’s surface and also by precipitation itself. Liquid raindrops and ice particles affect the microwave energy differently, so each channel is sensitive to a different precipitation type. With the addition of four new channels, the GPM Core Observatory is the first spacecraft designed to detect light rain and snowfall from space.

In addition to seeing all types of rain, GMI’s technological advancements allow the instrument to identify rain structures as small as about 3 to 9 miles (5 to 15 kilometers) across. This higher resolution is a significant improvement over the capability of an earlier instrument flown on the Tropical Rainfall Measurement Mission in 1997.

“You can clearly see them in the GMI data because the resolution is that much better,” said Skofronick-Jackson.

The DPR instrument adds another dimension to the observations that puts the data into high relief. The radar sends signals that bounce off the raindrops and snowflakes to reveal the 3D structure of the entire storm. Like GMI, its two frequencies are sensitive to different rain and snow particle sizes. One frequency senses heavy and moderate rain. A new, second radar frequency is sensitive to lighter rainfall and snowfall.

“Both return independent measurements of the size of raindrops or snowflakes and how they are distributed within the weather system,” said DPR scientist Bob Meneghini at Goddard. “DPR allows scientists to see at what height different types of rain and snow or a mixture occur — details that show what is happening inside sometimes complicated storm systems.”

The DPR data, combined with data from GMI, also contribute to more accurate rain estimates. Scientists use the data from both instruments to calculate the rain rate, which is how much rain or snow falls to Earth. Rain rate is one of the Core Observatory’s essential measurements for understanding where water is on Earth and where it’s going.

“All this new information comes together to help us better understand how fresh water moves through Earth’s system and contributes to things like floods and droughts,” said Skofronick-Jackson.

GMI was built by Ball Aerospace & Technologies, Corp., in Boulder, Colo., under contract to NASA. DPR was developed by JAXA with the National Institute of Information and Communication Technology.

These first GPM Core Observatory images were captured during the first few weeks after launch, when mission controllers at the NASA Goddard Mission Operations Center put the spacecraft and its science instruments through their paces to ensure they were healthy and functioning as expected. The engineering team calibrates the sensors, and Goddard’s team at the Precipitation Processing System verifies the accuracy of the data.

This initial science data from the GPM Core Observatory will be validated and then released for free by September online at:

http://pps.gsfc.nasa.gov

For more information and the GPM mission, visit:

https://www.nasa.gov/gpm

and

http://www.jaxa.jp/projects/sat/gpm/index_e.html

The GPM Core Observatory was the first of five planned Earth science launches for the agency in 2014. The joint NASA/JAXA mission will study rain and snow around the world, joining with an international network of partner satellites to make global observations every three hours.

NASA monitors Earth’s vital signs from land, air and space with a fleet of satellites and ambitious airborne and ground-based observation campaigns. NASA develops new ways to observe and study Earth’s interconnected natural systems with long-term data records and computer analysis tools to better see how our planet is changing. The agency shares this unique knowledge with the global community and works with institutions in the United States and around the world that contribute to understanding and protecting our home planet.

For more information about NASA’s Earth science activities in 2014, visit:

https://www.nasa.gov/earthrightnow