NASA is assessing the feasibility of adding a crew to the first integrated flight of the agency’s Space Launch System (SLS) rocket and Orion spacecraft, Exploration Mission-1 (EM-1). NASA is building new deep space capabilities to take humans farther into the solar system than we have ever traveled, and ultimately to Mars.

Acting Administrator Robert Lightfoot announced Feb. 15 that he had asked William Gerstenmaier, associate administrator for NASA’s Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate in Washington, to conduct the study, and it is now underway. NASA expects it to be completed in early spring.

The assessment will review the technical feasibility, risks, benefits, additional work required, resources needed and any associated schedule impacts to add crew to the first mission.

“Our priority is to ensure the safe and effective execution of all our planned exploration missions with the Orion spacecraft and Space Launch System rocket,” said Gerstenmaier. “This is an assessment and not a decision as the primary mission for EM-1 remains an uncrewed flight test.”

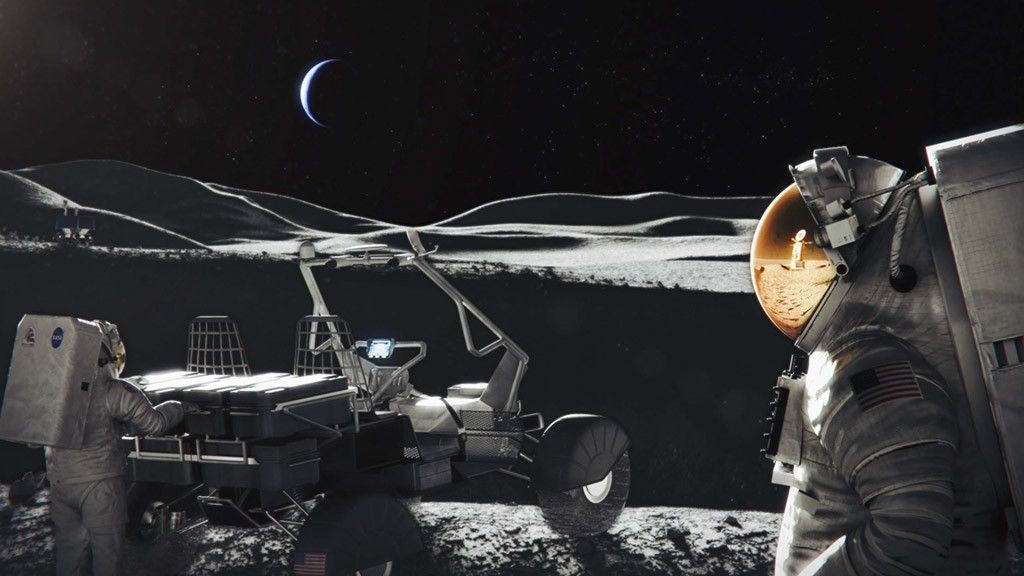

The assessment is evaluating the advantages and disadvantages of this concept with regards to short- and long-term goals of achieving deep space exploration capabilities for the nation. It will assume launching two crew members in mid-2019, and consider adjustments to the current EM-1 mission profile.

During the first mission of SLS and Orion, NASA plans to send the spacecraft into a distant lunar retrograde orbit, which will require additional propulsion moves, a flyby of the moon and return trajectory burns. The mission is planned as a challenging trajectory to test maneuvers and the environment of space expected on future missions to deep space. If the agency decides to put crew on the first flight, the mission profile for Exploration Mission-2 would likely replace it, which is an approximately eight-day mission with a multi-translunar injection with a free return trajectory.

NASA is investigating hardware changes associated with the system that will be needed if crew are to be added to EM-1. As a starting condition, NASA would maintain the Interim Cryogenic Propulsion stage for the first flight. The agency will also consider moving up the ascent abort test for Orion before the mission.

Regardless of the outcome for the study, the feasibility assessment does not conflict with NASA’s ongoing work schedules for the first two missions. Hardware for the first flight has already started arriving at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, where the missions will launch from the agency’s historic Pad 39B.

NASA recently completed the installation of the final topmost level in the Vehicle Assembly Building at Kennedy, completing the 10 levels of work platforms, 20 platform halves altogether, that will surround the rocket and the Orion spacecraft and allow access during processing for missions. In the last month, major construction was completed on the largest new SLS structural test stand, and engineers are now installing equipment needed to test the rocket’s biggest fuel tank. The stand is critical for ensuring SLS’s liquid hydrogen tank can withstand the extreme forces of launch and ascent on its first flight. In a lab at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, engineers simulated conditions that astronauts in spacesuits would experience when the Orion spacecraft is vibrating during launch on its way to deep space destinations to assess how well the crew can interact with the displays and controls they will use to monitor Orion’s systems and operate the spacecraft when necessary.

NASA is leveraging the very best the country has to offer on its deep space exploration plans, and it’s advancing the national economy. The SLS and Orion missions, coupled with record levels of private investment in space, will help put the agency and America in a position to unlock the mysteries of space and to ensure this nation’s world preeminence in exploring the cosmos.