Puerto Rico now has an air quality warning system that provides three days of advance notice about potentially harmful dust that travels across the Atlantic Ocean from the Sahara Desert.

NASA Earth-observing satellite data have shown that dust can ride air currents for 6,000 miles or more, affecting air quality that can be hazardous to human health. The project is led by NASA-funded researcher Pablo Méndez-Lázaro.

“Being able to see this dust before it arrives is a critical tool for public health,” said Méndez-Lázaro, an associate professor at the University of Puerto Rico Medical Sciences Campus in San Juan. “We alerted federal and state agencies as well as medical doctors, which gave them time to alert the public and vulnerable populations like people with asthma. Before, decision-makers lacked the specific information to help the public protect themselves in advance.”

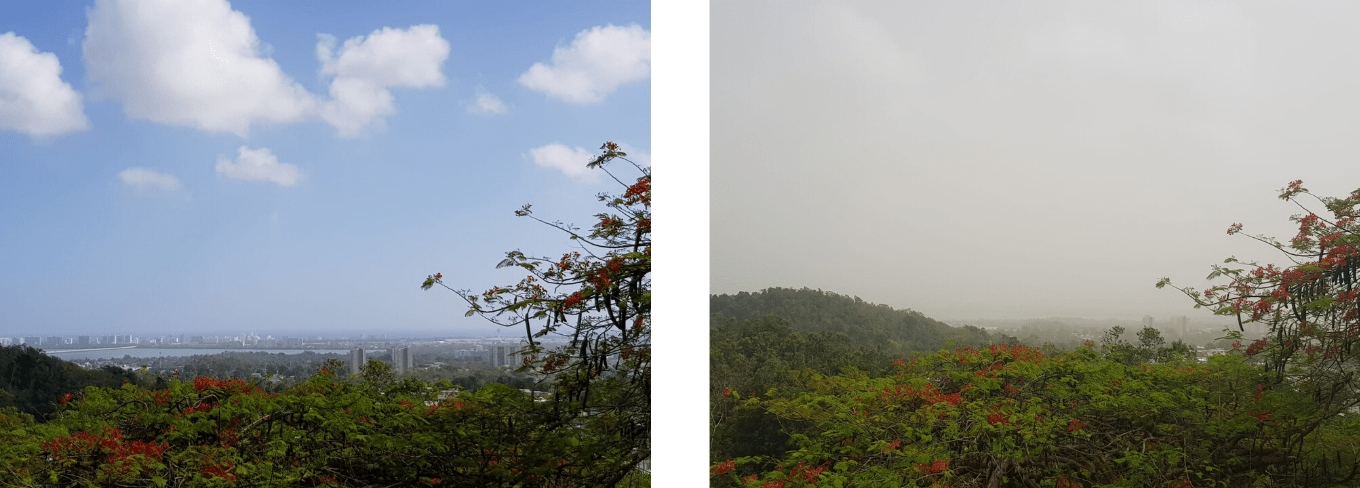

Dust often travels across the Atlantic and is a natural fertilizer for plants and coral, but the dust, especially in large quantities, causes poor visibility and air quality. It affects human health by causing irritation of eyes, nose and throat and it often contains fine particulates of silica and other minerals that are of a size that can easily infiltrate and irritate lung tissue.

“Vulnerable populations like children, the elderly and people with asthma or other pre-existing health conditions can be adversely affected,” Méndez-Lázaro said. “So, getting three additional days of warning can give people time to prepare.”

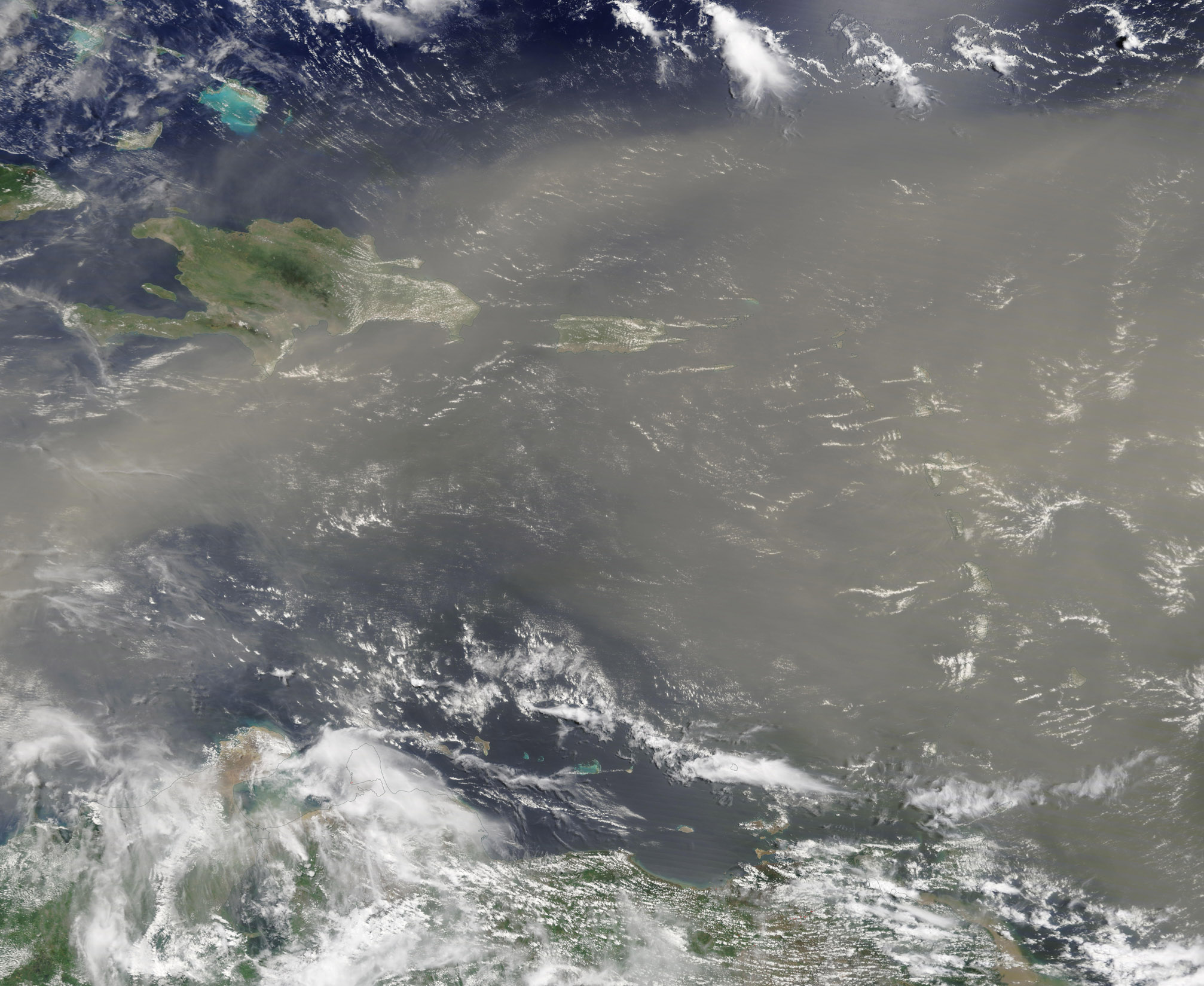

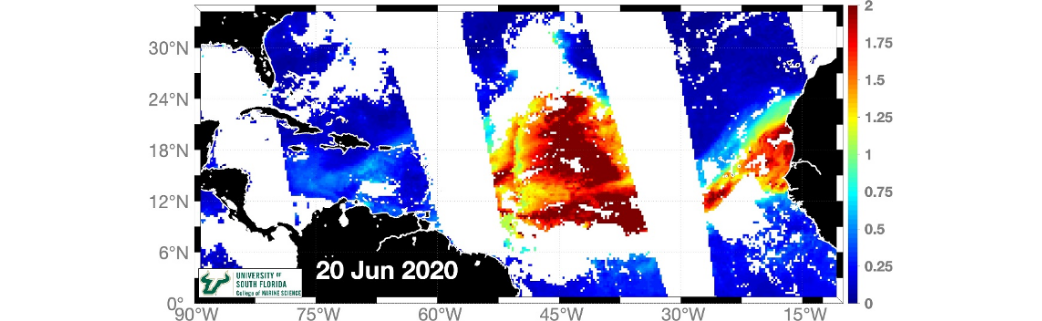

Méndez-Lázaro’s air quality monitoring system was in place just in time for the historically large cloud of Saharan dust reaching Puerto Rico in June. “We saw the dust cloud forming and crossing the Atlantic almost a week before it arrived in Puerto Rico,” Méndez-Lázaro said.

His team swung into action, contacting federal and state health agencies like the Puerto Rico Department of Health, the National Weather Service-San Juan Office and the Department of Natural Resources-Office of Air Quality.

As a result, the Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response (OPHPR) and the Emergency Management Office in Puerto Rico issued a press release with suggestions and recommendations to protect public health. In addition, during the dust event OPHPR helped keep the public informed through their Facebook page, while Méndez-Lázaro’s team also provided updates through the University of Puerto Rico’s Facebook pages.

The team reached out directly to the medical doctors already collaborating with their research team to raise awareness of the upcoming hazardous conditions, allowing them to alert their at-risk patients. “Having those three days allowed people to prepare to take steps like staying indoors or taking needed medication,” Méndez-Lázaro said. In turn, the doctors informed Méndez-Lázaro’s team about the health coverage they delivered during the event, helping the NASA team understand how patients responded to these warnings.

The team also did a Facebook Live broadcast with local meteorologist Ada Monzón that reached 374,000 people, and a Facebook Live broadcast with National Weather Service – San Juan Office. The broadcasts explained the hazardous conditions while providing preparedness measures and recommendations.

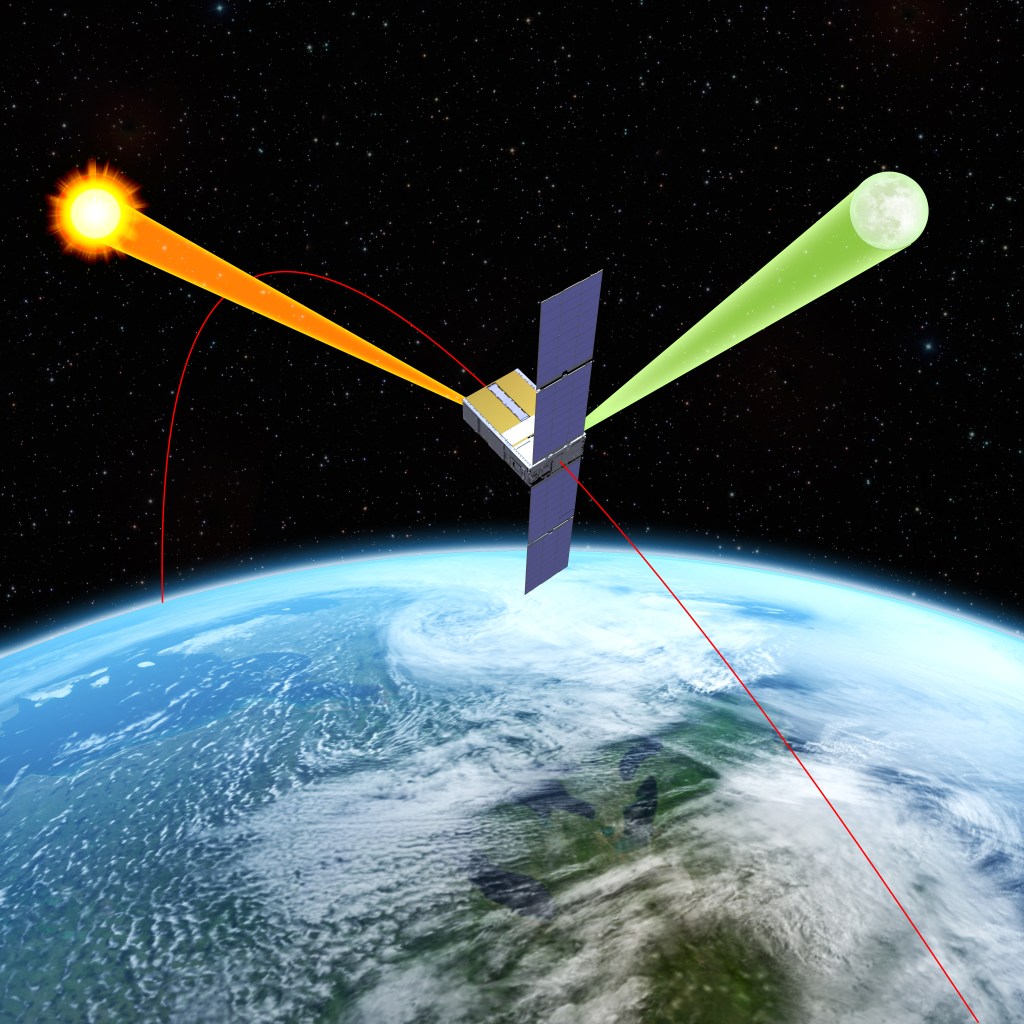

In setting up the air quality system, Méndez-Lázaro’s team installed on-the-ground air monitors as well as analyzed data from Earth-observing satellites. As Saharan dust travels across the Atlantic, it reflects visible and infrared light, which is detected by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) GOES-16 (EAST) satellite; the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometers (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites; and the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) on the joint NASA/NOAA Suomi NPP satellite.

While satellites collect data from orbit, Olga Mayol-Bracero and others on Méndez-Lázaro’s team also took samples from the ground-based air monitors. Using a technique called light scattering to assess the dust samples, they could discern if the particles were from Saharan dust or local pollution sources. By confirming the origin of the dust samples on the ground, the team was able to confirm predictions they had made based on satellite data about when the dust would make landfall. Ensuring the team’s predictions were correct resulted in public officials in Puerto Rico having reliable information three days before the arrival of potentially hazardous Saharan dust.

Achieving these three days of lead time took Méndez-Lázaro’s team three years of overcoming one unusual obstacle after another, from a hurricane to an earthquake to a global pandemic.

The 2020 Saharan dust storm was just the most recent event affecting the project and local residents of the island. In January 2020, a significant earthquake interrupted communications in Puerto Rico. Then, the spread of coronavirus (COVID-19) around the world led to travel restrictions, preventing the team from installing a round of instruments for air quality monitoring in the city of San Juan.

Even before those challenges, the team had to overcome significant adversity to get the system up and running. Three years ago, in summer 2017, Méndez-Lázaro’s team was just preparing to present to NASA this applied research idea of tracking the movement of dust from the Sahara Desert across the ocean. Then one of the most powerful storms to hit Puerto Rico arrived; Hurricane Maria, the first Category 4 cyclone to hit the island since 1932.

Because Méndez-Lázaro’s team is part of a medical college, they helped with hurricane response efforts – including providing supplies, medical assistance and educational material on environmental health and hygiene issues like water, air and food quality. “Working on a medical science campus, we have access to physicians and medicine. We were able to form a public health brigade five to six days after the hurricane – even outside the scope of our project – to visit communities unable to get access to medical services.”

In the wake of the hurricane’s devastation, citizens and businesses began using portable electric generators which affected air quality in a way that public health officials were not expecting. This was a turning point for the NASA project, giving Méndez-Lázaro’s team the idea to incorporate this growing source of pollution in their research proposal. They worked through power, internet and phone outages to prepare a new proposal for the NASA Earth Applied Sciences Program – and it was accepted.

Since then, Méndez-Lázaro has worked with patients, doctors and decision-makers to understand the information that local communities need to make decisions on air quality management. He discovered that many residents were not aware that dust was a threat to their health – and realized that education efforts would be critical for the success of this early warning system.

“We can send out a warning, but it’s no good if people aren’t listening.” said Méndez-Lázaro. “Our challenge is also to help people understand why this matters and what their options are to protect themselves. This is especially important to the most vulnerable – kids, the elderly and patients with preexisting conditions are most susceptible to African dust.”

As they prepared focus group discussions with doctors and residents, a political crisis in summer 2019 led to the resignation of the governor of Puerto Rico. This event interrupted funding at the public university, but the team was able to restore access to lab equipment and finished collecting feedback on the types of educational outreach and warnings that would best help the community.

“After all these obstacles, we visited Puerto Rico and expected their activities to have come to a standstill,” said John Haynes, head of NASA’s Health and Air Quality program area. “Instead, we saw several hundred partners, researchers and community practitioners who were excited to contribute to this project and continue advancing the study of air quality for public health.”

Despite all the challenges, Méndez-Lázaro sees the opportunity to make things better for the future. “Sometimes, it’s overwhelming when you try to get your head above water and these things push you back down,” he said. “But I’ve also seen them as opportunities to get stronger for Puerto Rico. A lot of learning experiences where, if we are smart enough to make it through, we can be better prepared for the future.”

Now, the team is focusing on next steps, including continuing their collaboration with researchers Dan Otis, Digna Rueda and Frank Muller-Karger from the University of South Florida in Tampa, who were instrumental in incorporating NASA satellite data from the VIIRS instrument. They also are strengthening their outreach for physicians, decision-makers and the general public including printed brochures, infographics and working with Ecoexploratorio the Museum of Science in Puerto Rico.

by Lia Poteet, NASA Earth Science Division