Planets can force their host stars to act younger than their age, according to a new study of multiple systems using NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory. This may be the best evidence to date that some planets apparently slow down the aging process for their host stars.

While the anti-aging property of “hot Jupiters” (that is, gas giant exoplanets that orbit a star at Mercury’s distance or closer) has been seen before, this result is the first time it has been systematically documented, providing the strongest test yet of this exotic phenomenon.

“In medicine, you need a lot of patients enrolled in a study to know if the effects are real or some sort of outlier,” said Nikoleta Ilic of the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam (AIP) in Germany, who led this new study. “The same can be true in astronomy, and this study gives us the confidence that these hot Jupiters are really making the stars they orbit act younger than they are.”

A hot Jupiter can potentially influence its host star by tidal forces, causing the star to spin more quickly than if it did not have such a planet. This more rapid rotation can make the host star more active and produce more X-rays, signs that are generally associated with stellar youth.

As with humans, however, there are many factors that can determine a star’s vitality. All stars will slow their rotation and activity and undergo fewer outbursts as they age. Because it is challenging to precisely determine the ages of most stars, it has been difficult for astronomers to identify whether a star is unusually active because it is being affected by a close-in planet, making it act younger than it really is, or because it is actually young.

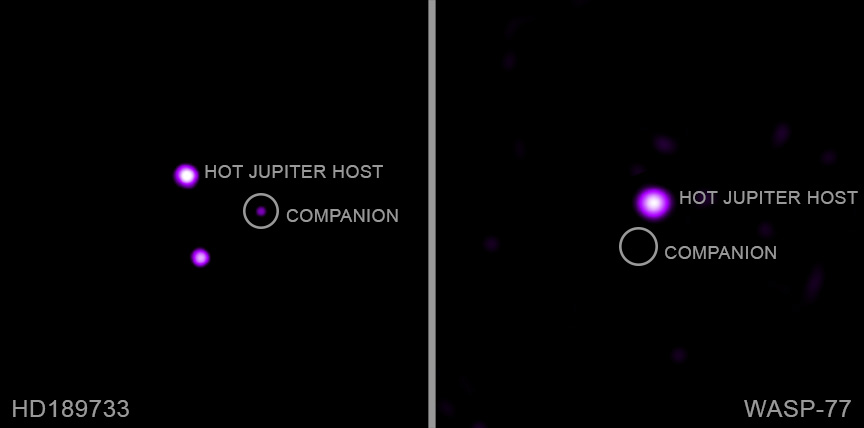

The new Chandra study led by Ilic approached this problem by looking at double-star (or “binary”) systems where the stars are widely separated but only one of them has a hot Jupiter orbiting it. Astronomers know that just like human twins, the stars in binary systems form at the same time. The separation between the stars is much too large for them to influence each other or for the hot Jupiter to affect the other star. This means they could use the planet-free star in the system as a control subject.

“It’s almost like using twins in a study where one twin lives in a completely different neighborhood that affects their health,” said co-author Katja Poppenhaeger, also of AIP. “By comparing one star with a nearby planet to its twin without one, we can study the differences in behavior of the same-aged stars.”

The team used the amount of X-rays to determine how “young” a star is acting. They looked for evidence of planet-to-star influence by studying almost three dozen systems in X-rays (the final sample contained 10 systems observed by Chandra and six by ESA’s XMM-Newton, with several observed by both). They found that the stars with hot Jupiters tended to be brighter in X-rays and therefore more active than their companion stars without hot Jupiters.

“In previous cases there were some very intriguing hints, but now we finally have statistical evidence that some planets are indeed influencing their stars and keeping them acting young,” said co-author Marzieh Hosseini, also of AIP. “Hopefully, future studies will help to uncover more systems to better understand this effect.”

A paper describing these results was published in the July 2022 issue of the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, and appears online.

NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center manages the Chandra program. The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory’s Chandra X-ray Center controls science operations from Cambridge, Massachusetts, and flight operations from Burlington, Massachusetts.

For more Chandra images, multimedia and related materials, visit: