Joshua Santora: Pluto is not a planet… or is it? Next on the “Rocket Ranch.”

[ Bird cries ]

Launch Countdown Sequence: EGS Program Chief Engineer, verify no constraints to launch. EGS Chief Engineer team has no constraints. I copy that. You are clear to launch. 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, and lift-off. All clear. Now passing through max Q, maximum dynamic pressure.

Welcome to space.

[ Whipcrack, theme music plays ]

Joshua Santora: Alright. So, I am in the booth now with Dr. Alan Stern. Dr. Stern, thank you for joining me today.

Alan Stern: Hey, Joshua, it’s great to be at “Rocket Ranch.”

Joshua Santora: Yeah, hey, listen. So, your résumé kind of reads like a… I don’t even know how to describe it. It’s impressive — like, everything from the — you’re a planetary scientist. You were the principle investigator for a number of scientific instruments that have flown in space, some aboard the Space Shuttle. You are the principle investigator for New Horizons. You were the associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate for a while. I think I saw you were short-listed to possibly be the administrator for NASA. And for a while there, you were working with some commercial companies, including Moon Express. One lifetime, right?

Alan Stern: You know, it’s good if you don’t need as much sleep as some other people, I guess.

[ Both laugh ]

Joshua Santora: So, and then the real question is, when you were a kid, what did you want to be when you grew up?

Alan Stern: I wanted to be a space explorer like every other kid I grew up with. It was just what every kid wanted to do. The United States was going to the moon, and everybody wanted to be a part of it. And I got to live my dream. It’s been awesome.

Joshua Santora: So, obviously, when people say, “I want to be a space explorer,” they often think about astronauts, and I don’t think you’ve been to space. Of all the things on your exhaustive résumé, I didn’t see actual astronaut travel yet.

Alan Stern: No, that’s right. That’s right. I tried very hard to be an astronaut. I was a finalist. I went through physicals, found that I’m very health, pretty well-adjusted mentally — at least I used to be.

Joshua Santora: [ Laughs ]

Alan Stern: But I was not selected. But, actually, I spent five years flying high-performance jets, NASA jets.

Joshua Santora: Awesome.

Alan Stern: And I have a research program that will be flying on Virgin Galactic…

Joshua Santora: Awesome.

Alan Stern:…as soon as they’re ready for commercial service. Through my company, the Southwest Research Institute — which is a private, nonprofit research institute with about 3,000 employees — I run a program where we’ll be doing astronomical and Earth-observation research from SpaceShipTwo.

Joshua Santora: So, for those that aren’t familiar, SpaceShipTwo is actually the Virgin Galactic Spaceship. It drops off an airplane, and so it’s an airdrop spaceship that actually carries people for suborbital flight, correct?

Alan Stern: That’s exactly right. It’s a suborbital spacecraft built for space tourism, but which we’re applying to space research to do kind of breakthrough, low-price, high-value-return research and education missions.

Joshua Santora: And so obviously you’re talking about sending some science up on board these suborbital flights, looking at minutes’ worth of microgravity experimentation. Are you on the experiments that gets to go at some point? Did you buy yourself a ticket yet?

Alan Stern: Oh, I’ll be flying several times. We have three tickets. That’s what I was referring to. And we’re going to be looking at the Earth’s atmosphere, we’re going to be looking at deep space, and we’re also going to be conducting biomedical experiments on ourselves by wearing a shuttle bio-med harness that measures blood pressure and respiration rates to study the transition from hyper-G on ascent, the high G’s that you have, to microgravity, and then back again at entry into high gravity again. So I’m looking to flying in space maybe as soon as next year or the year after.

Joshua Santora: So, Dr. Stern, obviously, you mentioned you grew up watching the Apollo Program, so you weren’t born yesterday, but it seems like you’re not letting that slow you down, that your career is even accelerating at this point to new heights — very literally.

Alan Stern: Well, you know, space is such a booming and blooming field at the same time. And, you know, the opportunities are just mushrooming. Why quit now?

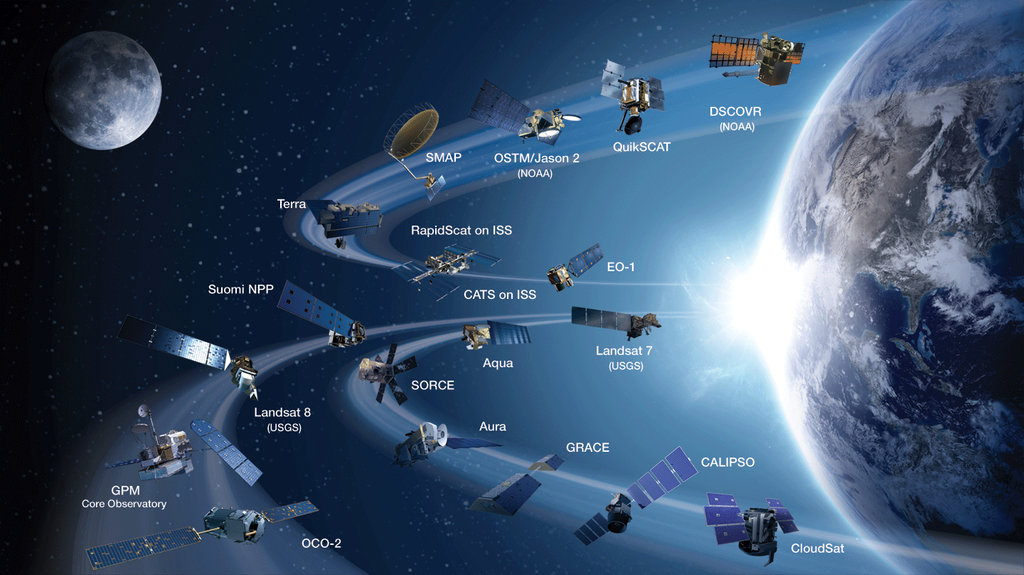

Joshua Santora: So, you mentioned the suborbital flights. Are you involved — or kind of what’s your perspective on this idea of the commercial space market right now? Because suborbital, we have Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic, are two of the big names right now getting into that kind of suborbital opportunities for tourism, as well as science research. We have the Commercial Crew Program here at NASA. We’re getting humans on board commercial spacecraft for the first time to Space Station. We have other companies like Bigalow, and we have companies like — who just launched out of New Zealand?

Alan Stern: [ Chuckles ] That’s Rocket Lab.

Joshua Santora: Rocket Lab, thank you. Yes, I think they said that that was like their ninth flight this year or something?

Alan Stern: That’s their ninth orbital flight, yeah, and eighth successful one. They’re really up-and-coming.

Joshua Santora: So, what’s your perspective on this market? Obviously, you mentioned the booming and blooming, and I don’t think anybody would argue with that, but kind of where do you see this going? And what’s the rate at which this is gonna move?

Alan Stern: Oh, it’s going at an accelerating rate, and truth in advertising is — I worked for as a consultant for both Branson and Bezos at their companies, at Virgin Galactic and at Blue Origin in the early part of this decade. When I was associative administrator for the Science Mission Directorate, I started a program for using these commercial vehicles. It’s now essentially morphed its way into the Space Technology Mission Directorate program called Flight Opportunities.

Joshua Santora: Awesome.

Alan Stern: And then, as I said, at Southwest Research Institute, I’m the principal investigator for a suborbital research program that will be flying scientists on these vehicles to conduct these experiments at much higher reliability and lower cost than we could with automation. Super excited about this and the advent of commercial orbital spaceflight. It’s really — I think the late teens and the ’20s are the breakout moment. And when I give public talks, I tell people, I said, “You know, this is the best time to be alive, to be in space ever.” Because people will look back in 200 years and say, “Back then, in the teens and ’20s, the beginning of the 21st century, that’s where ‘Star Trek’ began.”

Joshua Santora: [ Laughs ] Yeah, it’s tough to — again, assuming that the rate is accelerating like you say it is — and I am not one to disagree with you — that seems inevitable.

Alan Stern: Just think about it. Let’s reel back 10 years.

Joshua Santora: Let’s do it.

Alan Stern: Okay? It’s not very far back, 2009.

Joshua Santora: No, not at all.

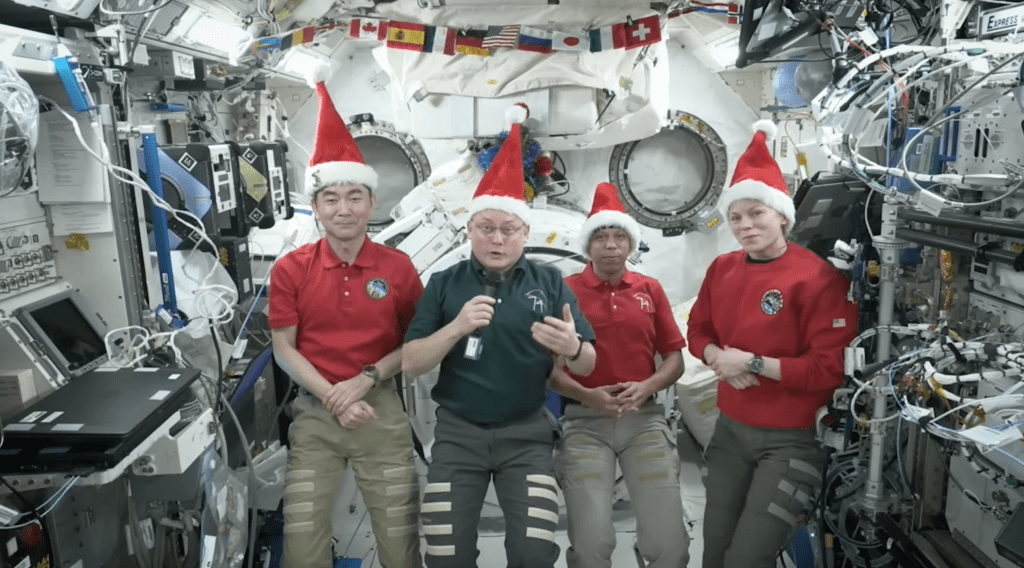

Alan Stern: We had a space shuttle, this fantastic flying machine, taking people in payloads up to the ISS. And in terms of human space light, the Russians had their vehicles, flying Soyuz up to ISS. That was it. Now let’s go forward not 10 years, but half as far, five years from now. Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic will be flying suborbital space flights with paying tourists, researchers, educators, maybe even NASA astronauts at the rate of one or more times per week…

Joshua Santora: Wow.

Alan Stern: Maybe daily. Then, on top of it, we’re going to have Orion flying. We’re going to have boots on the moon, men and women exploring the lunar surface for the first time in half a century in person, doing what robots still can’t do, which is the fieldwork that really requires humans on the spot.

Joshua Santora: Sure.

Alan Stern: We’re going to be turning our attention to Mars, and, at the same time, we’re going to have commercial crew vehicles from Boeing and SpaceX that are regularly shuttling astronauts and researchers, nonprofessional astronauts, maybe people like myself back and forth to the ISS and even commercial space stations. Compare that to what was going on 10 years ago.

Joshua Santora: Yeah.

Alan Stern: How could you say anything except it’s booming and blooming?

Joshua Santora: Yeah, yeah. You mentioned, obviously, you’re a planetary scientist, so one of your expertise lies in that field, so thinking about kind of the exploration and expansion to the moon, certainly, most kind of… we’ll call them Joe on the street. Most of them kind of think of, “Unless you’re getting to somewhere like to the moon, we aren’t doing anything different or new.”

Alan Stern: Mm-hmm.

Joshua Santora: So do you kind of look at this move towards a colony on the moon or Mars or even farther — I know you mentioned earlier to me you are working on a mission for Europa, headed to Europa. So what does this all kind of look like moving forward in exploring our solar system?

Alan Stern: Well, it’s amazing. We have the robotic fleet of spacecraft like Europa Clipper that’s going to be studying the ocean beneath Europa’s surface. We have Mars Sample Return coming up. Go ahead.

Joshua Santora: Do you do that with a giant drill? Are we just sending, like, a giant drill to Europa to just, like, carve a hole in the ice? Is that really the goal?

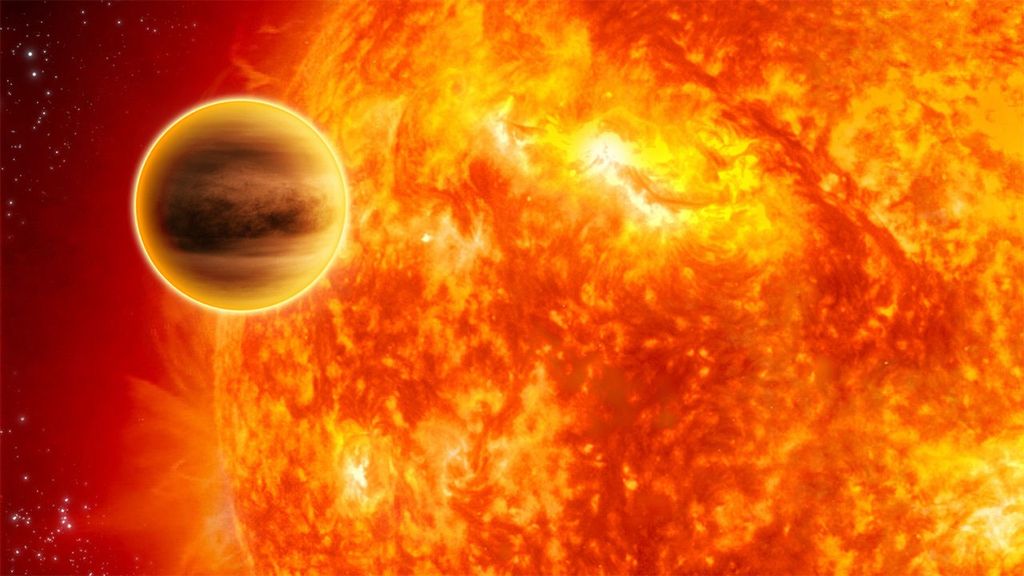

Alan Stern: That’ll be some future mission in which we’ll go down beneath the ice. Europa Clipper is actually a mission that orbits Jupiter and makes dozens of close flybys to Europa, which is this planet-sized moon of Jupiter, which has an ocean on the inside, beneath the ice, and which is very likely spewing ocean material out through geysers into space. And this very sophisticated robotic spacecraft called Europa Clipper will be studying the geology, the geophysics, the geysers, and maybe even sampling material coming out of those geysers as the spacecraft flies through it to make a precursor set of observations to lead us to a future surface mission.

Joshua Santora: And when you say we’re gonna gather these resources, hopefully, that are kind of flying off of Europa, how close are we talking about getting to this thing that you’re hoping to capture some of those?

Alan Stern: Yeah, so we’re going to go right down on the deck. If you made Europa a beach ball, some of the flybys would be as close as just a fraction of an inch above the surface of that beach ball.

Joshua Santora: Oh, wow.

Alan Stern: Other flybys will be further back because we want to get the global view, and those are both good types of science, so it’s not always about how close you go. But we’re going to get right down there on the deck.

Joshua Santora: That’s awesome. And I want to go back — you were mentioning Mars and kind of our exploration towards Mars.

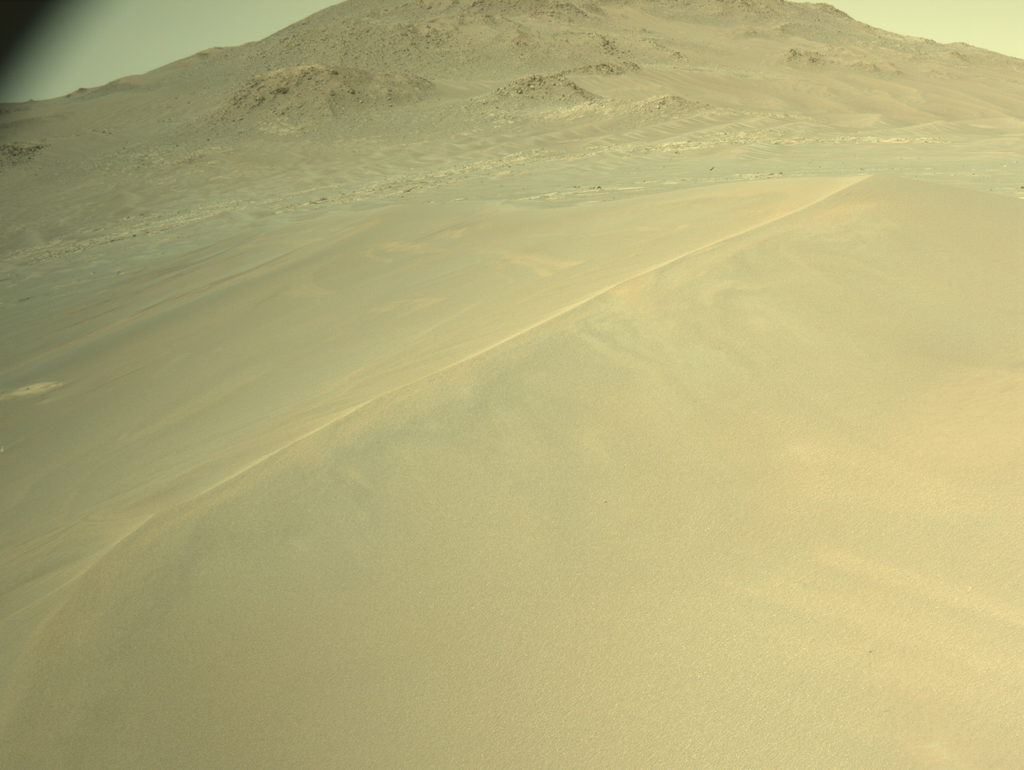

Alan Stern: Well, for Mars, for the moon, and for asteroids in between, the big next thing after Mars Sample Return is going to be humans — human bases on the moon, on Mars, probably on asteroids, as well. I spent a month down at South Pole early in my career, doing astronomy from the South Pole. And I think that we will have lunar bases and then Mars bases that have similar scope to what the National Science Foundation does down at South Pole, within the lifetimes of people who are in their careers now. It’s going to be incredibly exciting, and it really is where “Star Trek” begins.

Joshua Santora: [ Chuckles ] So, when you get asked the question like, “Why bother?” — because there are people right now, high-profile people, that are saying, “Eh, Mars isn’t worth the hassle.” How do you, as a planetary scientist — obviously, there’s a lot to discover and explore there, but is it worth sending people there on this nine-month journey, on this planet that’s ultimately currently a hostile environment for humans, and trying to set up these habitats there?

Alan Stern: Well, you know, a long time ago, Arizona was a pretty hostile environment for humans, and it was even worse because other humans were chasing you with lethal weapons.

Joshua Santora: [ Chuckles ]

Alan Stern: We won’t find that on Mars.

Joshua Santora: [ Chuckles ] We hope not.

Alan Stern: Right, but if you think about the value of what we’re doing — and I don’t want to discount it, but I’m not talking about the value of rewriting textbooks and expanding our knowledge and doing epochal science like finding out how prevalent life is in the solar system, right? If you think about the United States as a world leader and setting the pace for the whole planet, space exploration is one important way we do that. It’s also soft power projection because every kid in every nation on the Earth reads in their science textbooks, and they have these brands that they read about. NASA’s a brand, but even when NASA isn’t mentioned, just the Hubble Space Telescope, the ISS, a mission like New Horizons, that’s soft power projection. They’re learning about what great things the United States does even in countries that don’t like us very much just because the kids are taught about space science. But way beyond that, the breakout moment for the economy, for space becoming a very important part of the economy, from colonization of other worlds, to applications like remote sensing, security, handheld communications on the Internet from any spot on the Earth, fire and disaster recovery, and then all the applications we haven’t thought of, including space tourism. Everybody wants to go to space. Everybody wants to see the Earth from space.

Joshua Santora: Yeah.

Alan Stern: Right? People want to actually walk on the moon and go to Mars, and it’s not possible yet, but later in this century, it will be. And to ask what is the value of that is a little bit like, you know, the naivete of asking the tinkerers with electronics a century and a half ago, “What’s all that research about? What’s ever gonna come of those things with the wires?”

[ Both laugh ]

Joshua Santora: Or, “The Internet’s just a fad. It’s just a fad.”

Alan Stern: Yeah, like that.

Joshua Santora: So, when you talk about the moon playing a part in our economy, can you flesh that out for me some more? Because I hear people say that — and, again, I don’t know that I can disagree, but how does that happen on a practical level?

Alan Stern: Yeah, well, I think, at first, it’ll be a “walk before we run” thing.

Joshua Santora: Sure.

Alan Stern: We will have a NASA/international presence on the moon at the South Pole that will be a research establishment, and private companies will be there selling services, right up through space tourism, I think. But then people will start to settle there, and very much like the push across the Americas centuries ago, little dots of light will start to appear across the surface of the moon as humans establish multiple locations, and we’ll have everything we have here on Earth eventually. There will be schools and hospitals and businesses and everything else because the solar system is this unlimited frontier with these tremendous resources and opportunities for our economy, coming across how many centuries into the future? I don’t know. But it’s humankind’s playground, if you will, it’s our backyard before we launched to the stars, when we have the technology to do that.

Joshua Santora: So you talk about kind of the expansion across the moon. Do you envision a time when you walk out your door here on Earth, and you look up at the moon and it’s not just reflecting the sun’s light anymore, but now you actually see lights being generated that are visible from Earth?

Alan Stern: I think about that a lot, and I think one of the most powerful things we can do, as soon as we set up the first outpost on the moon –

Joshua Santora: To prove we did it and send a light back?

Alan Stern: Not to prove we did it, but to be inspirational.

Joshua Santora: Mm.

Alan Stern: If you can see that base through binoculars or even naked eye because there’s a searchlight there, or some equivalent thereof…

Joshua Santora: Yeah.

Alan Stern: When moms and dads can take their kids out in the yard and point up at the moon and say, “You see that light there on the moon?

Joshua Santora: Mm.

Alan Stern: “People live there.” I think that’s gonna be so powerful, and not just for STEM education, just for feeling the power of what humans can do.

Joshua Santora: Mm.

Alan Stern: That we can live off our cradle of the Earth, that we can move out into the universe in a real way. Not in the way that Apollo did it, to be there for a few moments or a weekend and come back, but that people really live and work there on another world, and, you know, Mars and the asteroids, eventually humans will go further. Those places are so much further away…

Joshua Santora: Yeah.

Alan Stern:…that although they’ll be very important, the moon is the only world close enough where you can look up, naked eye, and you will be able to see the outposts and eventually the cities that are there.

Joshua Santora: Mm. Do you see anything stopping humanity? Like, are there dangers that we have to encounter, or we don’t even kind of foresee coming that will just, like, thwart this effort?

Alan Stern: There might be, but I think that the very great odds are that this is what we’re gonna be doing more and more of in every decade of this century, and because it’s now flowering into the commercial — the private sector — so that it doesn’t just depend upon votes and legislatures and government budgets, but that it’s the civil plus the commercial partnered together in public, private enterprises, and, to some extent, just private things and just civil things, also, that it’s a much more robust and nuanced space economy that we’re looking at then the old-school 1960s centrally planned “Let’s compete with the Soviets” model that entirely depended upon the whim and will of administrations and Congresses.

Joshua Santora: Mm. So thinking about, obviously, your work — People know your name. They probably know it as associated with New Horizons and the Pluto fly-by — I think 2015 was the year we saw the fly-by happen. So certainly, like, I feel like congratulations are always in order for that. I’m sure it feels good to have it out there exploring, but — So can you kind of recap, for our listeners who maybe aren’t familiar, take us through, like, a fly-by of the development, the launch, and then that fly-by that happened and kind of now what’s coming up in the future?

Alan Stern: Right. Sure. Happy to do that, and let me say, you know, New Horizons has been the mission of a lifetime to be involved in, and 2,500 American men and women were involved in designing, building, and flying that spacecraft out to the edge of our solar system. New Horizons made the first exploration of the Pluto system and then went on out into the Kuiper Belt and has explored the farthest worlds ever explored, the farthest places in human history. It’s a single little spacecraft that was built up in Maryland by the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab in a mission that I am, to this day, pinching myself that I’ve been the Principal Investigator for. I have a tremendous team of people. The flight team is about 50 men and women. Around the fly-bys, it bulks up to a couple hundred with very intensive activity for just a few weeks.

Joshua Santora: Sure.

Alan Stern: Back when we were building it, as I said, there were thousands of people involved, including in the launch vehicle here at the Cape where we launched it from, but it’s just a single small robotic spacecraft, very high-tech, built in the early 2000s, launched in 2006 that’s now further than 4 billion miles — billion with a “B”, as Carl Sagan would say — “billion” miles away, right? Been traveling a million miles a day for almost 14 years now, and it’s not going slowly. It’s the fastest spacecraft ever launched. It got to the moon not in three days like Apollo, but in 9 hours, and it’s been traveling at that clip ever since for 14 years. It’s not as far away as the Voyagers because they launched in the ’70s.

Joshua Santora: Sure. It’s gonna take a while to get there.

Alan Stern: But it explored worlds farther away than the Voyagers ever went to.

Joshua Santora: Sure.

Alan Stern: And it’s revolutionized our knowledge about small planets and about the origin of planets through the studies of the Kuiper Belt, which has the power and fuel and, frankly, the health onboard the spacecraft to keep doing this for another 20 years.

Joshua Santora: There’s been years of development. There was 9 years of flight. So, Pluto is so far away that we’re traveling a million miles a day and it took us 9 years to get there, expedited by, I think, a gravity assist around Jupiter…

Alan Stern: That’s right.

Joshua Santora:…that we almost missed out on. It would have cost us, like, 4 more years if we had been a little bit later.

Alan Stern: But we got it!

Joshua Santora: But we got it.

Alan Stern: We launched on time from the Cape, and we made it to Jupiter.

Joshua Santora: So you’ve waited decades for this moment, and the fly-by’s happening. There’s still a little bit of concern that you’re gonna fly right through some debris and mess up instruments.

Alan Stern: Or destroy-shred the spacecraft.

Joshua Santora: Or just shred the spacecraft.

Alan Stern: Yeah.

Joshua Santora: And so tell me about this day with your team, and what are the emotions, and what’s kind of like the process of watching this data come back?

Alan Stern: You know, Joshua, it’s so hard to describe. When you work with people so long, in our case from 2001 to 2015, from the time we competed with other teams as to who was gonna get selected by NASA to be the team to build and fly this, and we had many problems in development because all space missions do, they’re complex.

Joshua Santora: Sure.

Alan Stern: We had many challenges. We overcame them. We had a textbook launch and a very long flight across the solar system. We planned for everything we could think of, and we brought in experts, helping us think of things we couldn’t even think of just to be prepared for contingencies.

Joshua Santora: Sure.

Alan Stern: And then when it worked, and when the first high-resolution images came back on the 14th of July 2015, which, by the way, was, to the very day, the 50th anniversary of the first images from Mars.

Joshua Santora: That’s awesome.

Alan Stern: Amazing.

Joshua Santora: That’s awesome.

Alan Stern: When that happened –

Joshua Santora: Did you time that? You planned that out, didn’t you?

Alan Stern: I wish I could say that we timed it that way. It just worked out. But, you know, when we saw those images, it’s not an exaggeration to say that adults cried.

Joshua Santora: Yeah.

Alan Stern: People who had worked on it that long, and there was no back-up, there was no second chance. It’s not like Voyager. There isn’t a New Horizons II if we got it wrong. You know? It was all make-or-break, and when it all worked out, to see — not just to see your work succeed but to see how excited people all around the world were and to see how provocative, how game-changing the science was, all of that at once was almost overwhelming. For some people, it was overwhelming, and it was super emotional, which I think is great. You know, space flight — We’re not all Spock.

Joshua Santora: There’s lots of emotions.

Alan Stern: Yeah.

Joshua Santora: No, that’s so good, and I enjoy getting to work with students and kind of talk about New Horizons over the past decade of my career — If I’m correct, I think that before 2015, the best shot we had at Pluto was basically four fuzzy pixels.

Alan Stern: That’s right, and that’s with the Hubble, which you can’t get a better telescope, right? It’s just so far away.

Joshua Santora: It’s so far.

Alan Stern: And the other interesting thing about it is that, in 2015, we had not been to a new planet. We had not sent a spacecraft to a wholly new, you know, large place since 1989. I was in graduate school. I finished my PhD that year, in December of that year, and that was the same year that Voyager made its last hurrah of planetary exploration by going through the Neptune system.

Joshua Santora: Cool.

Alan Stern: So for anybody that was born from the early ’80s on, they were either not alive then or they were too young to remember it, and by the time that we got to 2015, according to Census Bureau records, 40% of the people in the United States, almost half, had never seen anything like this before.

Joshua Santora: Wow.

Alan Stern: They’d never been a part of this kind of raw first time, unwrap the present and see what’s inside, see what a whole new planet’s all about.

Joshua Santora: Yeah.

Alan Stern: See a point of light become a planet almost overnight. And I think that was part of the tidal wave of excitement, was for a new generation to actually get to take part in that and to see how cool it was.

Joshua Santora: Yeah.

Alan Stern: And, to this day, you know, we’re four-plus years later. Not only I, but others on my team, we give public talks, we go to schools, universities, corporations, planetarium shows, we go to conventions, and everywhere we go, people come up to us and say — Somebody will tell you at almost any talk, “This was life-changing for me. It made me want to be an engineer.”

Joshua Santora: Mm.

Alan Stern: “It made me want to be a scientist.” “It turned my son or daughter around to be a good student.” I’ve heard so many stories like this, and it, for me, as a scientist, it’s something that was really unanticipated. I knew people would groove on it, but I didn’t think it would be life-changing, that something we would do –

Joshua Santora: Yeah.

Alan Stern:…that was really dorky and geeky and, you know, done for knowledge would be so inspiring to other people.

Joshua Santora: Yeah. Yeah, one of the things that I tried to convey when I speak about New Horizons is pulling up just these magnificent and beautiful images that were captured of Pluto, and then reminding everybody that the camera that took that left Earth 9 years earlier, and it was built years before that, and the picture looked like it was a modern high-definition image. And so it’s remarkable to think about, like, the amount of technology and, like, that brilliant work that stood the test of, I mean, more or less, like 13, 14 years…

Alan Stern: Yeah.

Joshua Santora:…from the time it was created until it got to fly by, and in a four-hour chunk, you got this data that I think you were still receiving a year-and-a-half later.

Alan Stern: It took about a year-and-a-half, yeah, it did. Yeah.

Joshua Santora: Which is unreal.

Alan Stern: Yeah.

Joshua Santora: And I would remiss if I didn’t ask the question because I would contend — Certainly I think this mission got the respect that it was due, but I think that a lot of attention was drawn to it especially because of the controversy over Pluto being a planet or not. And so I’ll pose the question to you, Dr. Stern. Is Pluto a planet?

Alan Stern: Of course it’s a planet. Take a look at it. If it came on the viewfinder of a starship on “Star Trek,” you would say they’re orbiting a planet. You wouldn’t know what else to call it, and neither do planetary scientists. The people who actually practice the field consider all these small planets, planets and use that in the scientific literature. Now, I realize the astronomers, the people that work on black holes and galaxies, you know, they had their say back in 2006, but other than the press, I really don’t know who ever bought that, and certainly, from a professional planetary scientist standpoint, you know, I would claim that the New Horizons team is more expert in this than almost anybody.

Joshua Santora: Mm.

Alan Stern: But you can go way beyond us. The general planetary science community calls these worlds planets in technical publications because we don’t know what else to call them. That’s what they are, and it doesn’t matter what they orbit with or what they orbit around or where they are, you know, just from a purely physics and geophysics standpoint, these worlds are planets.

Joshua Santora: Hm.

Alan Stern: And Pluto is kind of the poster child for what we call dwarf planets. What a lot of people don’t know and maybe a lot of listeners don’t know is that the sun is called a dwarf star by astronomers.

Joshua Santora: Right.

Alan Stern: And just as dwarf stars are stars and dwarf galaxies are galaxies, dwarf planets are planets. They’re just smaller ones. They’re the size of continents. The surface are of Pluto is not very different from the surface area of the United States. It’s a big place.

Joshua Santora: Interesting.

Alan Stern: You wouldn’t want to walk across it.

Joshua Santora: So, and then, again, thinking about New Horizons, the fly-by was obviously of Pluto — That’s the primary mission.

Alan Stern: Mm-hmm.

Joshua Santora: That’s what it was built for.

Alan Stern: Right.

Joshua Santora: But certainly built with some excess capacity there. So I know there’s a process to kind of get extensions, but you guys were approved for extensions, so what’s happened since 2015? Because New Horizons is still going and still sending data as far as I know.

Alan Stern: We are. We had — Our most recent fly-by took place on January 1st, just 37 minutes East Coast Time into the new year.

Joshua Santora: Cool.

Alan Stern: And beyond where we encountered Pluto, a billion miles beyond — just a billion miles.

Joshua Santora: Just a billion miles, no big deal.

Alan Stern: Yeah, yeah. Just between us on New Horizons. Another billion miles out, we did a close fly-by of this geeky object called 2014 MU69.

Joshua Santora: Is this the hourglass-looking one?

Alan Stern: Yeah.

Joshua Santora: Okay.

Alan Stern: It kind of looks like that, or a snowman, maybe, you would say.

Joshua Santora: Sure. Yeah.

Alan Stern: But it’s really one of the building blocks of the planets out there, and it’s been untouched for 4.5 billion years. It’s kind of archaeological dig into history of the solar system. Nobody had ever been something this ancient and untouched before. It was a very tough technical challenge. We had to hunt it down in the darkness out there and fly by it at 32,000 miles an hour with, you know, literally only about an hour-and-a-half to get all the data, and, again, no second chance.

Joshua Santora: Yeah. Yeah.

Alan Stern: And we made all that work, and then we’ve been spooling the data back because the data transmission rates are low. It’s still coming back, and it will still be coming back through most of next year to finish the job on that fly-by. And then we’re gonna look for other targets. Whether we’ll find one or not depends as much on Mother Nature as anything else. We have all these great giant ground-based telescopes. We have telescopes onboard New Horizons, we have the Hubble space telescope, and we’re gonna use all those techniques to look for another fly-by target, still further out, billions of miles further out, and we have the fuel and the power to fly New Horizons into the late 2030s.

Joshua Santora: Cool.

Alan Stern: We’ll probably be beyond the Kuiper Belt by the late 2020s.

Joshua Santora: Okay.

Alan Stern: So 8, 9 years from now. But that’s a long time. So we’re gonna be looking, and we’re gonna propose a second extended mission to go on. We made, I think, an A-plus at Pluto. I think we made an A-plus at MU69. The spacecraft is in great health, and, you know, that’s what we were sent out here to do, is to go exploring, and there’s nothing else coming this way. There probably will be missions in the future, but, right now, there’s not even one that’s been approved to get started.

Joshua Santora: Sure.

Alan Stern: So for a long time, this is it for Kuiper Belt exploration, and we’re gonna milk New Horizons to get as much out of it as we possibly can because we put our brains and our hearts into building it. Now it’s there. We want to use it!

Joshua Santora: Sure. Sure.

Alan Stern: Yeah.

Joshua Santora: So past the Kuiper Belt, is New Horizons set up to kind of analyze intergalactic space?

Alan Stern: If we get that far, yes.

Joshua Santora: Okay.

Alan Stern: And, you know, the Voyagers are out there in the interstellar medium now. They’re beyond the sun’s cocoon called the heliosphere.

Joshua Santora: Okay.

Alan Stern: And we have the possibility — We have much more sophisticated sensors onboard than what they could build in the ’70s.

Joshua Santora: Sure.

Alan Stern: Right? Right?

Joshua Santora: Right.

Alan Stern: Right? I mean, think of what a computer was like then. It filled the room and had blinking lights, and it couldn’t figure out anything compared to your iPhone or Droid.

Joshua Santora: Right.

Alan Stern: But, anyway, New Horizons was built to do this exploration and to go on much further, and not only for the interstellar exploration but to go beyond the Kuiper Belt and study the inner reaches of the so-called Oort Cloud of our solar system are all things where we’re the only spaceship that’s out there that can do anything about it. And we want to get as much out of it — We’ve already paid for it.

Joshua Santora: Sure.

Alan Stern: The ongoing cost of operating it every year is just tiny compared to what it cost to build it and launch it and fly it out there.

Joshua Santora: Sure.

Alan Stern: So now, you know, it’s just more presents to unwrap every year.

Joshua Santora: Does it feel like it’s Christmas every year?

Alan Stern: It feels like it’s Christmas every month on New Horizons.

Joshua Santora: Awesome. Very cool.

Alan Stern: Because there’s new data coming down all the time.

Joshua Santora: So, I know you mentioned your sub-orbital science research work. Obviously, New Horizons — I want to give a tip of the hat, again, I think you mentioned — I think it was an Atlas V it launched on?

Alan Stern: We did launch — We launched on an Atlas V in 2006, just a few months before the United Launch Alliance was in business. At that time, it was a Lockheed rocket with a Boeing upper stage.

Joshua Santora: Oh, interesting. Okay.

Alan Stern: And those two companies formed ULA together in a 50-50 partnership.

Joshua Santora: Awesome.

Alan Stern: So we were not under the ULA banner when it launched, but ULA operates the Atlas line now.

Joshua Santora: Oh, interesting.

Alan Stern: And we’re very grateful to all those engineers and executives and everybody else that worked at Lockheed and at Boeing to create that launch vehicle that worked so perfectly.

Joshua Santora: Yeah, so –

Alan Stern: And the folks at the Cape that got it launched.

Joshua Santora: And want to also shout-out to the Launch Services Program folks involved in that process.

Alan Stern: You know, the LSP was just tremendous for us, and we even had technical challenges with regard to the rocket because of some testing taking place on other models, and the LSP team, the Engineering team at LSP got us cleared to launch and did it, really, under the gun on schedule because we had to launch in January of 2006 to get the Jupiter fly-by that we talked about earlier.

Joshua Santora: Yeah.

Alan Stern: And they didn’t skip any steps, but they worked — They really burned the midnight oil to make sure that they got their work done in order to get us cleared to launch so that we would make that critical launch window.

Joshua Santora: Cool.

Alan Stern: Amazing job. I will never forget it.

Joshua Santora: Cool. And you’re working on another one of the missions that they’re helping to manage, or a couple. Lucy is one of them. I know — I think Lucy’s targeted for like a late 2021 launch date?

Alan Stern: We’re gonna launch two years from this past October.

Joshua Santora: Okay.

Alan Stern: So just under two years from now.

Joshua Santora: Cool.

Alan Stern: On a mission to explore a class of asteroids called the Jovian Trojans that are actually leftover relics from the formation days of the Giant Planets. Really excited about that. And then involved in Europa Clipper. We don’t know what it’s gonna launch on just yet. That’s somebody else’s to decide.

Joshua Santora: Sure.

Alan Stern: But the spacecraft is coming along very nicely, and it’ll be ready to launch in the early ’20s also.

Joshua Santora: All right, so I’m gonna — hopefully I won’t come across as too ignorant here, but all those things you just mentioned, I have never heard of them before — the spacer going to investigate and these Giant Planets you speak of, can you give me a little bit more on those?

Alan Stern: Mm-hmm. Well, sure. Sure.

Joshua Santora: Obviously you’re going to learn more about them, so you don’t know as much as you will in a couple years from now.

Alan Stern: Right. Right. Right. And, you know, they are — they’re gonna be a lot better-known once we go there, and they’re gonna be more in the public consciousness.

Joshua Santora: Sure.

Alan Stern: Just as other words that are closer to home got explored, now, you know, we know about them. The Jovian Trojans are a vast field of asteroids that orbit in Jupiter’s orbit. They were trapped by Jupiter’s gravity in these stable pockets that lead and trail the Giant Planet Jupiter. But what’s important is not where they orbit and how they got trapped, it’s that they were — they are samples left over from the formation days of the Giant Planets, and they have been kept in this deep freeze of space, like a perfect preservation of the chemistry and the formation conditions of these bodies that will teach us about not only how the Giant Planets formed, but about the bombardment of the Earth, how volatiles and organics were originally transported to the terrestrial planets, including the Earth, and, you know, just from a scientific standpoint, just understanding the story of our solar system, how did it come to be? How did it come to be arranged this way? And so this is a very important mission, and it’s a relatively low-cost planetary mission. New Horizons was only about a quarter as expensive as Voyager.

Joshua Santora: Oh, wow.

Alan Stern: Lucy is half as expensive as New Horizons.

Joshua Santora: Wow.

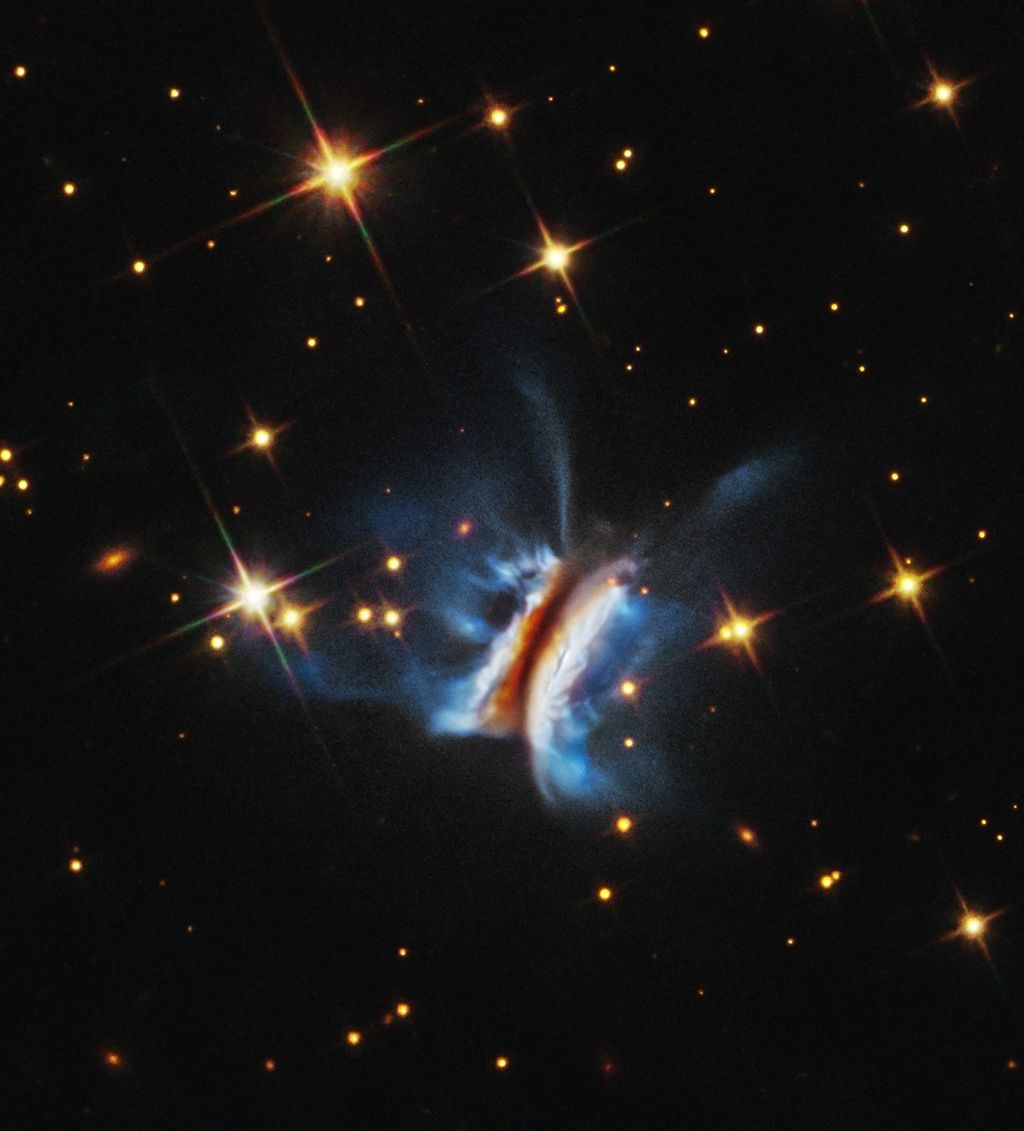

Alan Stern: And then Europa Clipper is a bigger mission with a much more bristling scientific payload than either New Horizons or Lucy, but it’s gonna do one of the most important things in the entirety of space science, which is look for habitable environments. These oceans that are so prevalent in the outer solar system, beneath the ice of satellites, or the Giant Planets, for that matter, Pluto, we think, almost certainly has an ocean on the inside, too.

Joshua Santora: Hm.

Alan Stern: These could be abodes for life, and much more hospitable in many ways than the surface of Mars. So even though they’re farther away, they have a higher astrobiological potential, and we’re just beginning their real exploration. Europa Clipper — pardon the pun, but it’s the ice-breaker mission for this whole field.

Joshua Santora: Awesome. We’re just about out of time, but I want to ask you — Dr. Stern, whip out your crystal ball for a second and tell me if you look forward, kind of as you see exploration in space the next 10 years, what’s the most exciting thing we see happen in the next decade?

Alan Stern: Wow. You made that so hard by — I don’t know how to pick one thing. I mean –

Joshua Santora: All right, well, give me a couple, then. Give me a couple.

Alan Stern: I just think that the advent of space tourism in which so many people from different walks of life are gonna get to do what only test pilots and scientists could do, which is see the Earth from space, and maybe even in 10 years, even have tourists that have been to the moon. It’s gonna be game-changing. I think the development of lunar outpost over the next 10 years, even the very earliest stages of it, like when the ISS was, you know, this tiny little thing in Earth orbit, is gonna be very powerful. The advent of worldwide Internet, where not just the first-world and second-world nations, but everybody on the Earth is connected…

Joshua Santora: Mm-hmm.

Alan Stern:…is gonna be very powerful.

Joshua Santora: Yeah.

Alan Stern: The search for life and habitability around other worlds in our solar system and across the galaxy — That’s another game-changer, and that’s before the things we haven’t thought of, you know, what comes out of nowhere the way that people didn’t really predict the Internet, but then it happened, and it changed the world. I think all of this is gonna be happening in the ’20s. It is just the most exciting time for space there has ever been.

Joshua Santora: All right, Dr. Stern, if people want to learn more about what you’re doing and kind of keep track of what you’re up to, how can they follow you?

Alan Stern: Well, I guess it’s like anybody else. You can go to my website, AlanStern.space. That’s A-L-A-N-S-T-E-R-N-dot-S-P-A-C-E. And I have a Twitter feed, and that’s just @AlanStern. A-L-A-N-S-T-E-R-N. Thanks for asking.

Joshua Santora: Awesome. Well, as you head out, I don’t think you’re going for necessarily just tourist-y purposes, but enjoy your time in space, suborbital flight here sooner than later. Good luck with Lucy and the other missions you got coming up. Dr. Stern, thanks for joining me.

Alan Stern: Thank you so much, Joshua.

Joshua Santora: I’m Joshua Santora, and that’s our show. Thanks for stopping by the “Rocket Ranch.” And special thanks to my guest, Dr. Alan Stern. To learn more about New Horizons, visit NASA.gov/NewHorizons. And to learn more about everything going on at the Kennedy Space Center, go to nasa.gov/kennedy. Check out NASA’s other podcasts to learn more about what’s happening at all of our centers at nasa.gov/podcasts. A special shout-out to our producer, John Sackman, our soundman, Lorne Mathre, editor, Michelle Stone, and special thanks to Mary McLachlan. And remember, on the “Rocket Ranch,” even the sky isn’t the limit.