Using NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and other X-ray observatories, astronomers have found evidence for what is likely one of the most extreme pulsars, or rotating neutron stars, ever detected. The source exhibits properties of a highly magnetized neutron star, or magnetar, yet its deduced spin period is thousands of times longer than any pulsar ever observed.

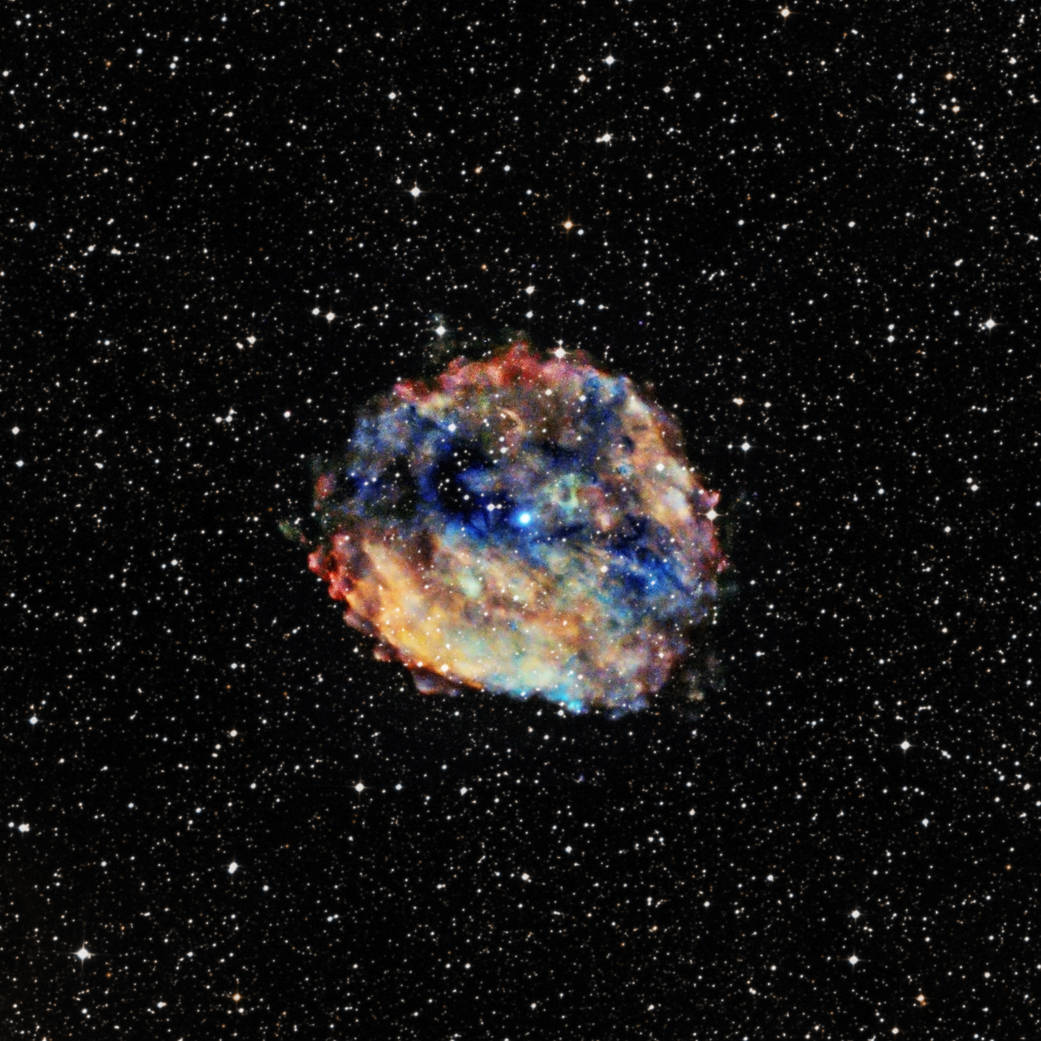

For decades, astronomers have known there is a dense, compact source at the center of RCW 103, the remains of a supernova explosion located about 9,000 light years from Earth. This composite image shows RCW 103 and its central source, known officially as 1E 161348-5055 (1E 1613, for short), in three bands of X-ray light detected by Chandra. In this image, the lowest energy X-rays from Chandra are red, the medium band is green, and the highest energy X-rays are blue. The bright blue X-ray source in the middle of RCW 103 is 1E 1613. The X-ray data have been combined with an optical image from the Digitized Sky Survey.

Observers had previously agreed that 1E 1613 is a neutron star, an extremely dense star created by the supernova that produced RCW 103. However, the regular variation in the X-ray brightness of the source, with a period of about six and a half hours, presented a puzzle. All proposed models had problems explaining this slow periodicity, but the main ideas were of either a spinning neutron star that is rotating extremely slowly because of an unexplained slow-down mechanism, or a faster-spinning neutron star that is in orbit with a normal star in a binary system.

On June 22, 2016, an instrument aboard NASA’s Swift telescope captured the release of a short burst of X-rays from 1E 1613. The Swift detection caught astronomers’ attention because the source exhibited intense, extremely rapid fluctuations on a time scale of milliseconds, similar to other known magnetars. These exotic objects possess the most powerful magnetic fields in the Universe –trillions of times that observed on the Sun – and can erupt with enormous amounts of energy.

Seeking to investigate further, a team of astronomers led by Nanda Rea of the University of Amsterdam quickly asked two other orbiting telescopes – NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array, or NuSTAR – to follow up with observations.

New data from this trio of high-energy telescopes, and archival data from Chandra, Swift and ESA’s XMM-Newton confirmed that 1E 1613 has the properties of a magnetar, making it only the 30th known. These properties include the relative amounts of X-rays produced at different energies and the way the neutron star cooled after the 2016 burst and another burst seen in 1999. The binary explanation is considered unlikely because the new data show that the strength of the periodic variation in X-rays changes dramatically both with the energy of the X-rays and with time. However, this behavior is typical for magnetars.

But the mystery of the slow spin remained. The source is rotating once every 24,000 seconds (6.67 hours), much slower than the slowest magnetars known until now, which spin around once every 10 seconds. This would make it the slowest spinning neutron star ever detected.

Astronomers expect that a single neutron star will be spinning quickly after its birth in the supernova explosion and will then slow down over time as it loses energy. However, the researchers estimate that the magnetar within RCW 103 is about 2,000 years old, which is not enough time for the pulsar to slow down to a period of 24,000 seconds by conventional means.

While it is still unclear why 1E 1613 is spinning so slowly, scientists do have some ideas. One leading scenario is that debris from the exploded star has fallen back onto magnetic field lines around the spinning neutron star, causing it to spin more slowly with time. Searches are currently being made for other very slowly spinning magnetars to study this idea in more detail.

Another group, led by Antonino D’Aì at the National Institute of Astrophysics (INAF) in Palermo, Italy, monitored 1E 1613 in X-rays using Swift and in the near-infrared and visible light using the 2.2-meter telescope at the European Southern Observatory at La Silla, Chile, to search for any low-energy counterpart to the X-ray burst. They also conclude that 1E 1613 is a magnetar with a very slow spin period.

A paper describing the findings of Rea’s team appears in the September 2, 2016, issue of The Astrophysical Journal Letters and is available online. The authors of that paper are Nanda Rea (University of Amsterdam and IEEC-CSIC, Spain), A. Borghese (Univ. of Amsterdam), P. Esposito (Univ. of Amsterdam), F. Coti Zelati (Univ. of Amsterdam, INAF, Insubria), M. Bachetti (INAF), G. L. Israel (INAF), A. De Luca (INAF).

A paper describing the findings of D’Aì’s team has been accepted for publication by Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society and is also available online.

NuSTAR is a Small Explorer mission led by the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena and managed by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, also in Pasadena, for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington.

NASA’s Swift satellite was launched in November 2004 and is managed by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, manages the Chandra program for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts, controls Chandra’s science and flight operations.

Image credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/University of Amsterdam/N.Rea et al; Optical: DSS

Read More from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory.

For more Chandra images, multimedia and related materials, visit: