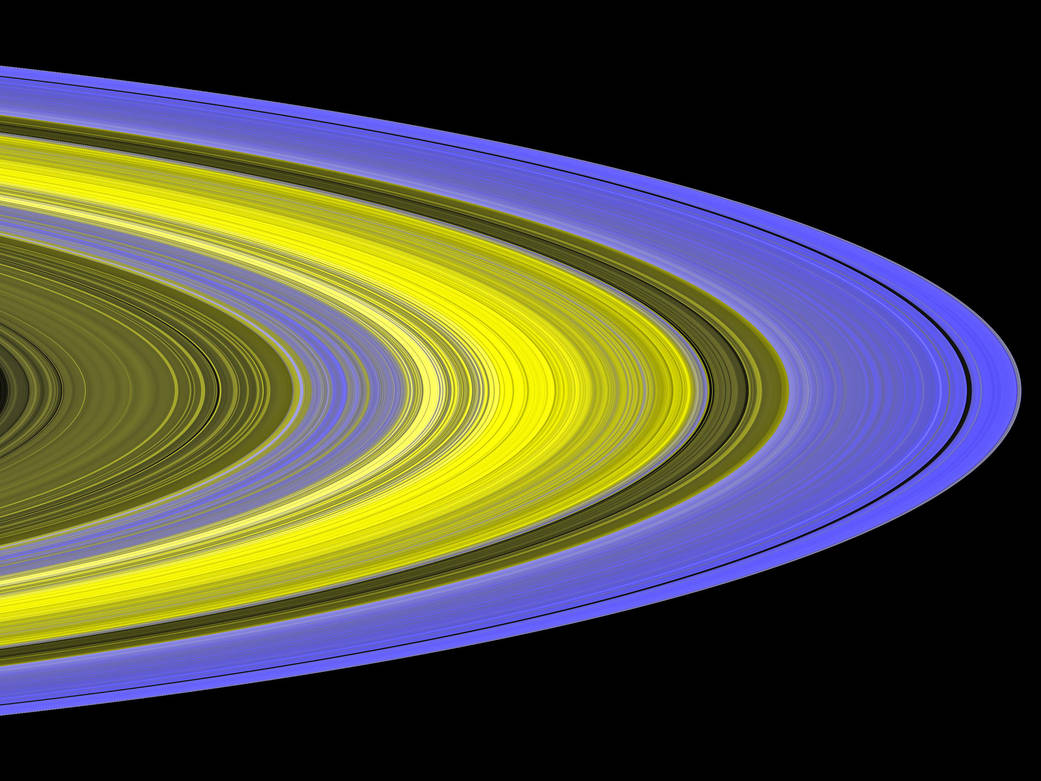

This false-color image of Saturn’s main rings was made by combining data from multiple star occultations using Cassini’s ultraviolet imaging spectrograph. An occultation occurs when one celestial body passes in front of another, thus hiding the other from view.

During occultations, scientists observe the brightness of a star as the rings pass in front of it. This provides a measurement of the amount of ring material between the spacecraft and the star.

Cassini has given scientists the most detailed view yet of Saturn’s densely packed B ring, which is densely packed with clumps, called self-gravity wakes, separated by nearly empty gaps. These clumps in Saturn’s B ring are neatly organized and constantly colliding, which surprised scientists.

The clumps in Saturn’s B ring, 30 to 50 meters (100 to 160 feet) across, are too small to be seen directly. However, scientists can map the distribution, shape and orientation of the clumps. Colors in this image indicate the orientation of clumps, and brightness indicates the density of ring particles. The formation of wakes is strongest in the bluer regions, where ring particles clump together in tilted wakes. Particles in the central yellow regions are too densely packed for any starlight to pass through it.

The ultraviolet imaging spectrograph measured the flickering of the star Alpha Arae as it passed by the rings Nov. 9 and 10, 2006.Image credit: NASA/JPL/University of Colorado

2 min read