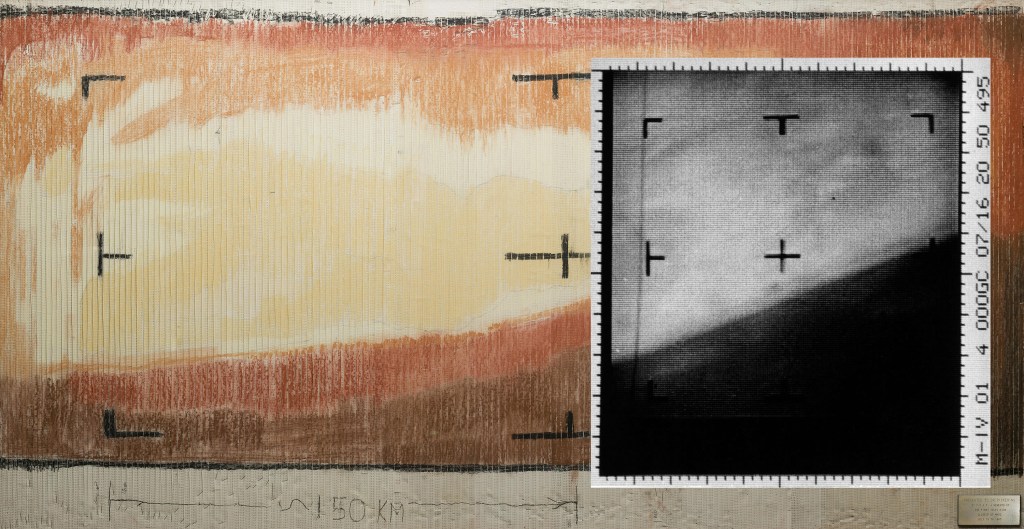

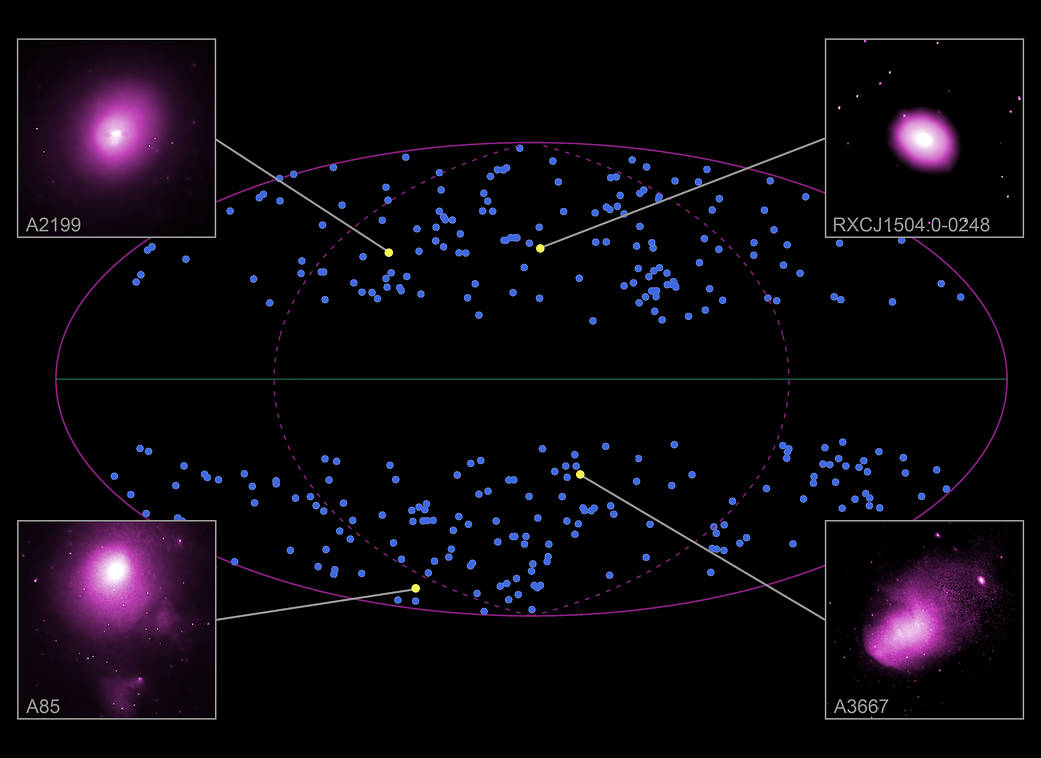

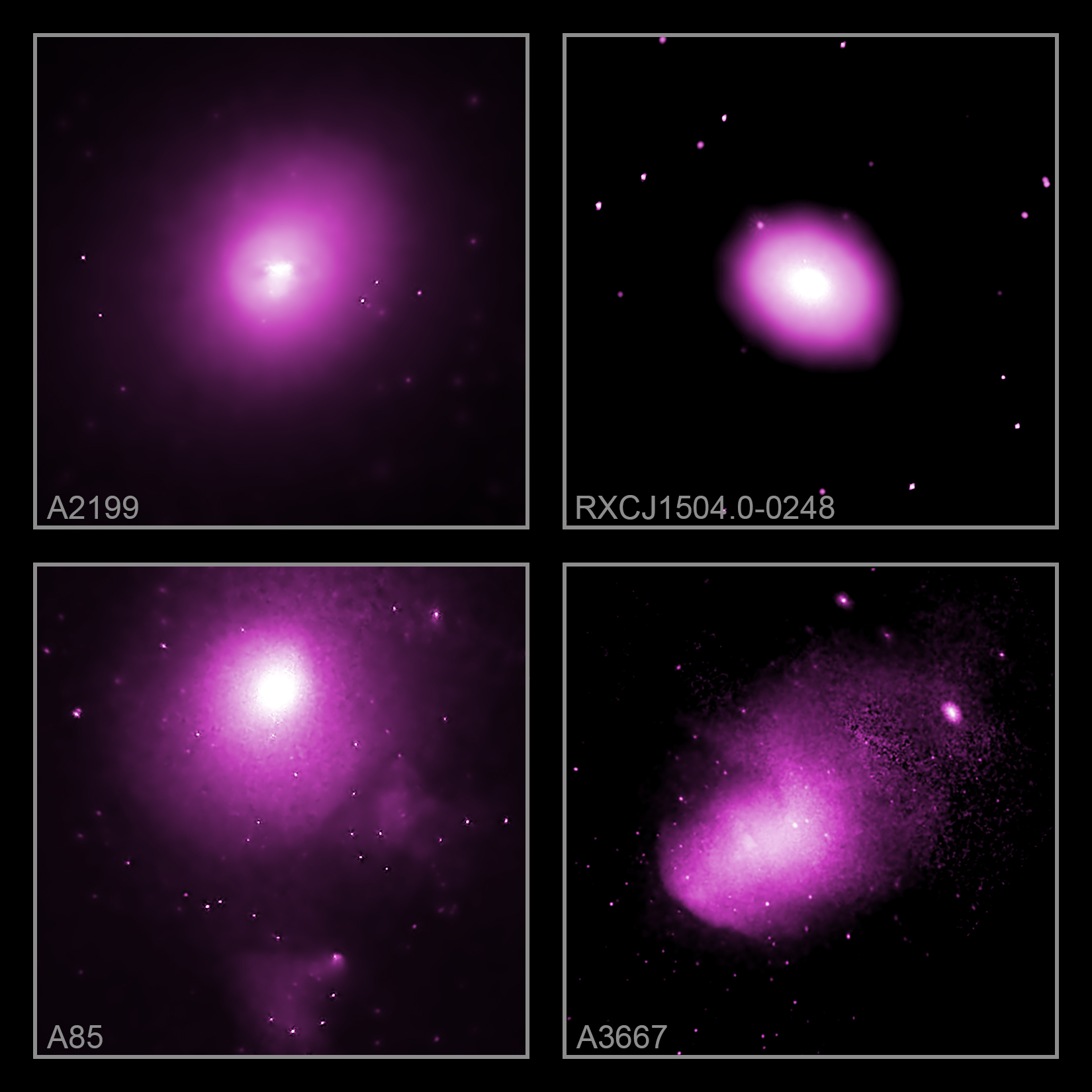

This graphic contains a map of the full sky and shows four of the hundreds of galaxy clusters that were analyzed to test whether the Universe is the same in all directions over large scales, as described in our latest press release. Galaxy clusters are the largest objects in the Universe bound by gravity and astronomers can use them to measure important cosmological properties. This latest study uses data from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and ESA’s XMM-Newton to investigate whether or not the Universe is “isotropic.”

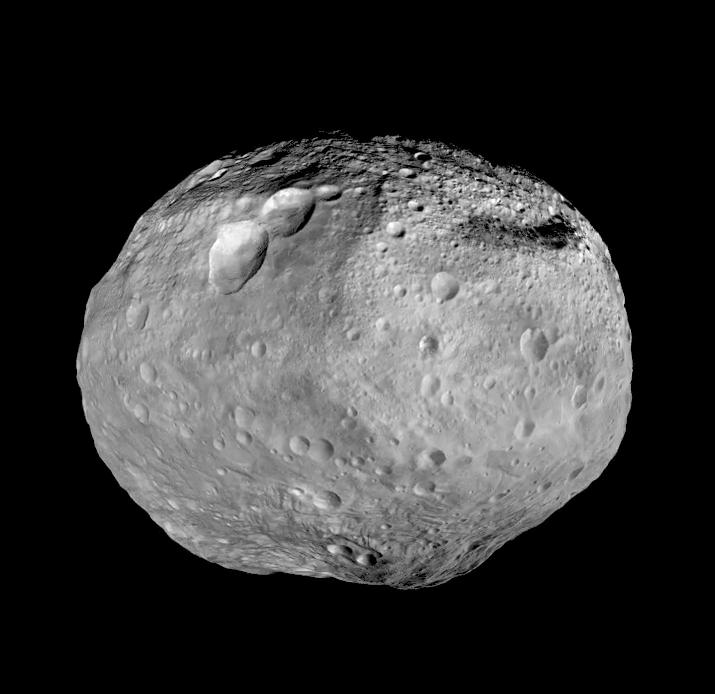

The sky map in this schematic is in “galactic coordinates,” with the plane of the Milky Way running along the middle (instead of the equator like is used for Earth). Galactic longitude runs in the horizontal, or “x” direction, and galactic latitude runs in the vertical, or “y” direction. The dark points show the location in the sky map of the 313 galaxy clusters observed with Chandra and XMM-Newton and included in this study. The four Chandra images of galaxy clusters from the new study are, in a clockwise direction from the top left, Abell 2199, RXJ1504.1-0248, Abell 3667 and Abell 85. Galaxy clusters with galactic latitudes less than 20 degrees were not included in the survey to avoid obscuration from the Galaxy itself, which has most of its stars, gas and dust along a thin plane. Similarly, galaxy clusters behind two nearby galaxies, the Small Magellanic Cloud and the Large Magellanic Cloud, and behind the Virgo galaxy cluster were not included to avoid obscuration.

Astronomers generally agree that after the Big Bang, the cosmos has continuously expanded like a baking loaf of raisin bread. As the bread bakes, the raisins (which represent cosmic objects like galaxies and galaxy clusters) all move away from one another as the entire loaf (representing space) expands. With an even mix the expansion should be uniform in all directions, as it should be with an isotropic universe.

This latest test uses a powerful, novel and independent technique and suggests the concept of an isotropic Universe may not entirely fit. The study capitalizes on the relationship between the temperature of the hot gas pervading a galaxy cluster and the amount of X-rays it produces, known as the cluster’s X-ray luminosity. The higher the temperature of the gas in a cluster, the higher the X-ray luminosity is. Once the temperature of the cluster gas is measured, the X-ray luminosity can be estimated. This method is independent of cosmological quantities, including the expansion speed of the universe.

Once they estimated the X-ray luminosities of their clusters using this technique, scientists then calculated luminosities using a different method that does depend on cosmological quantities, including the universe’s expansion speed. The results gave the researchers apparent expansion speeds across the whole sky – revealing that the universe appears to be moving away from us faster in some directions than others.

The authors of this new study came up with two possible explanations for their results that involve cosmology. One of these explanations is that large groups of galaxy clusters might be moving together, but not because of cosmic expansion. For example, it is possible some nearby clusters are being pulled in the same direction by the gravity of groups of other galaxy clusters. If the motion is rapid enough it could lead to errors in estimating the luminosities of the clusters.

A second possible explanation is that the universe is not actually the same in all directions. One intriguing reason could be that dark energy – the mysterious force that seems to be driving acceleration of the expansion of the universe – is itself not uniform. In other words, the X-rays may reveal that dark energy is stronger in some parts of the universe than others, causing different expansion rates.

Either of these two cosmological explanations would have significant consequences. The astronomical community must perform other scrutinized tests obtaining consistent results every time to truly know if the concept of an isotropic Universe should be reconsidered.

A paper describing these results will appear in the April 2020 issue of the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics and is available online. The authors are Konstantinos Migkas (University of Bonn, Germany), Gerrit Schellenberger (Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian), Thomas Reiprich, Florian Pacaud and Miriam Elizabeth Ramos-Ceja (University of Bonn), and Lorenzo Lovisari (CfA).

Image credit: NASA/CXC/Univ. of Bonn/K. Migkas et al.

Read more from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory.

For more Chandra images, multimedia and related materials, visit: