As many Americans prepare for a socially distanced Thanksgiving meal, some may be aware that NASA helped develop the tiny, highly efficient video cameras in the devices that will allow virtual family dinners, and a few may know it was the space agency that first modernized conference calling. But there’s an even more important contribution from NASA on the table: food that’s safe to eat.

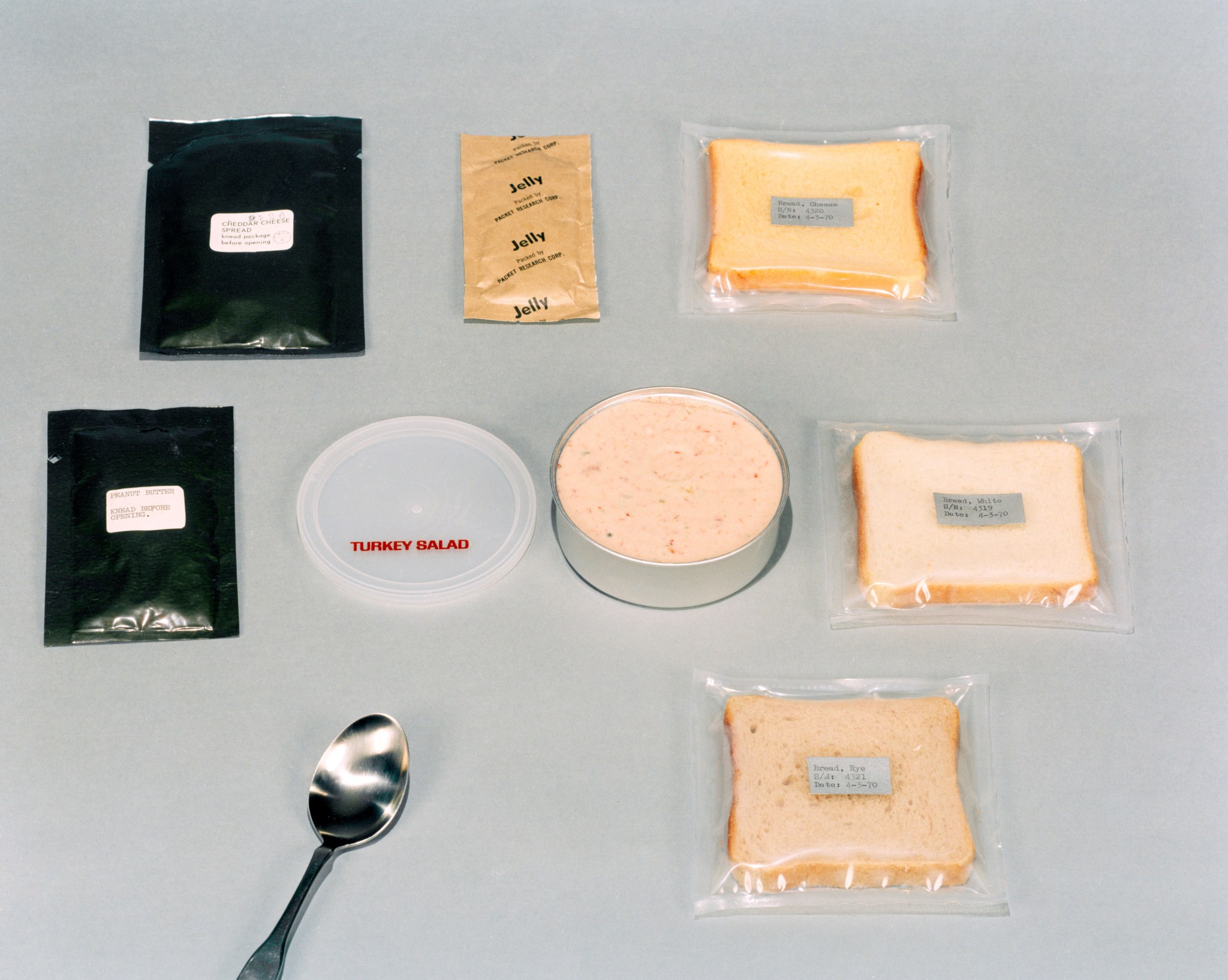

Today, outbreaks of illness from packaged food are exceedingly rare, in part because the industry has almost universally adopted a system created for astronaut food in the early days of the Apollo program.

All the companies putting food on your Thanksgiving table use this approach – called the Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) system – and cite it as a major reason for the reduction in foodborne illness.

“It’s one of these things where we maybe don’t appreciate the benefits, we just take them for granted now, because HACCP is so ingrained in how we produce food,” said Alice Johnson, vice president of food safety and quality at Butterball Turkey LLC.

Analyze Hazards, Establish Control

The effort began at the Manned Spacecraft Center, now NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, in the early 1960s. Leading the way was Paul Lachance, whose background in nutrition at the Air Force’s Quartermaster Food and Container Institute was complemented by that of Howard Bauman, a microbiologist at Pillsbury, which partnered with NASA in this mission to provide safe food for the astronauts on the Gemini and Apollo missions.

Whereas earlier efforts focused on thoroughly testing end products, the Apollo Program Office placed a heavy emphasis on identifying and controlling any potential points of failure. The guidelines were written with space system hardware in mind, but food was also deemed mission-critical.

The approach Lachance and Bauman came up with at NASA’s direction was to identify points in the food production process where hazards could be introduced, determine how those hazards could be prevented, and monitor these critical control points with frequent measurements. NASA also required the team to keep meticulous records, which became another critical aspect of HACCP.

No one in the Apollo Program Office could have imagined they had set in motion a system that would improve food safety around the world – and it took decades for that to happen. But Bauman liked what he saw. He went on to become one of the most outspoken advocates for HACCP’s widespread adoption.

Pillsbury presented HACCP to the world at the first National Conference on Food Protection in 1971. Following two deaths from botulism, a serious food-borne illness caused by bacterial toxins, that summer, the National Canners Association and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) agreed to make low-acid canned food manufacturers the first to be subject to HACCP regulations. In 1993, an outbreak of food poisoning at a fast-food chain caused the meat and poultry industries to lobby for regulation to restore consumer confidence. Within a decade, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) had HACCP regulations in place for meat and poultry, and the FDA required the system for all seafood and juice producers.

Then came the 2011 FDA Food Safety Modernization Act. Although it doesn’t mention HACCP by name, the law phased in HACCP-like requirements across the remaining U.S. food producers that register with the FDA and also requires importers to verify that foreign manufacturers comply with these requirements. The last businesses were phased into the requirements in 2018.

“It basically mandates HACCP on steroids for all other FDA-regulated food products,” said Jenny Scott, senior advisor in the FDA’s Office of Food Safety, although many producers had long before put HACCP-like systems in place voluntarily and required their suppliers to do likewise.

“Brainstorming What Could Go Wrong”

Because the system is intended to target the specific hazards in a given production line, every HACCP plan is different. At a Butterball plant, Johnson said, control points for a HACCP plan likely include a checkpoint to look for any “farm residue” like pesticide, refrigeration that has to be below a certain temperature, and antimicrobial sprays or dip tanks.

Katy Latimer, vice president of research and development for Ocean Spray, said critical control points for cranberry sauce include the washing area where berries are first received, filtration and metal detection points where any foreign materials are removed, a heat treatment pasteurization area, and acidity checks, among others.

By requiring producers to analyze and address the risks of each product line individually, HACCP has changed the relationship between companies and regulators, Johnson said. “Instead of going to the government and saying, ‘We’ve got a problem, what do you think we should do?’ it’s up to us to decide what to do and justify why we’re doing it.”

“It takes a team of quality assurance folks, engineers, and scientists to identify critical control points for safety and quality,” said Latimer, calling it a process of “brainstorming what could go wrong.”

While it takes time and money, Mark Fryling, vice president of global food safety and quality at General Mills, which now owns Pillsbury, said it costs far less than a product recall and the resulting damage to a brand name.

By mandating meticulous records, HACCP also makes inspections more effective, said Scott at the FDA. Before, inspectors only saw a snapshot of plant conditions on the day of their visit, she explained. Now, “We still poke and sniff, but records give a better picture of whether they’re consistently in control of their processes.”

The result, said Scott Seebohm, deputy director of the policy development staff for the USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service, is a marked improvement in food safety. It can be difficult to quantify this improvement, because while industry has gotten better at preventing outbreaks, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have gotten better at detecting them. Nevertheless, despite an increase in known outbreaks caused by Salmonella, for example, through the late 1990s and early 2000s, the total number of people infected dropped.

Meanwhile, this spinoff from the Apollo program has gone global: much of Europe took up HACCP many years ago, and many other suppliers around the world use HACCP-like systems to be allowed to export to countries that require it.

Latimer at Ocean Spray said deaths from botulism, linked to unsafe practices, initially gave rise to the packaged-food industry, and “it’s really cool to see how the space program moved that along.” A small NASA program helped the industry make good on its most basic promise – that of safe, worry-free meals, on Thanksgiving and all year round.

NASA has a long history of transferring technology to the private sector. The agency’s Spinoff publication profiles NASA technologies that have transformed into commercial products and services, demonstrating the broader benefits of America’s investment in its space program. Spinoff is a publication of the Technology Transfer program in NASA’s Space Technology Mission Directorate.

To learn more about this NASA spinoff and how NASA brings space technology down to Earth, read the original article or visit:

By Mike DiCicco

NASA’s Spinoff Publication