[Editorial Headnote: The transition team assembled to advise President-elect Ronald Reagan on space issues consisted of individuals with long experience in the field, both within and outside of NASA. It was chaired by George M. Low, who had left NASA in 1976 after a long career to become President of the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, New York. The team’s report provided a detailed set of recommendations and actions for the incoming administration. A copy of this report is available in the NASA Historical Reference Collection, NASA History Office, NASA Headquarters, Washington, DC.]

December 19, 1980

Mr. Richard Fairbanks, Director

Transition Resources and Development Group

1726 M Street, NW

Washington, DC 20270

Dear Mr. Fairbanks:

I am pleased to submit the report of the transition team for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). We hope you will find that it presents a balanced view of the status of the agency, its problems, strengths, end potentials. Team members received full cooperation from NASA officials. Our group worked together well, with frequent unanimity on identification and resolution of issues.

Recognizing that many members have been involved in the past with space programs, the team was particularly sensitive to its appearance of a pro-space bias. Members worked hard to prepare an objective report, with minimal personal advocacy. Team members have asked, however, that in this letter I emphasize our view that NASA and its civil space program represent an opportunity for positive accomplishment by the Reagan administration. In contrast with many government agencies that are mired in seemingly insoluble controversy, NASA can be many things in the future—the best in American accomplishment and inspiration for citizens.

We are pleased to have had the opportunity to aid the new administration and trust that our report will serve you and the next NASA Administrator well. The members of the team and I will be happy to provide additional consultation should it be needed.

Sincerely,

George M. Low

Team Leader

NASA Transition Team

…

[1]

I. Introduction

A. Overview

In 1958 the people of the United States set out to lead the world in space. By 1970 they had achieved their goal. Men walked on the moon, scientific satellites opened new windows to the universe, and communications satellites and new technologies brought economic return. With these came new knowledge and ideas, a sense of pride, and national prestige.

In 1980, by contrast, United States leadership and preeminence are seriously threatened and measurably eroded. The Soviet Union has established an essentially permanent manned presence in space, and is using this presence to meet economic, military, and foreign policy goals. Japan is broadcasting directly from space to individual homes and business, and France is moving ahead of the United States in preparing to reap the economic benefits of satellite resource observation. Ironically, U.S. commercial enterprises are turning to France to launch their satellites. In space science, the United States has decided to forego the rare opportunity to visit Halley’s comet in 1986, yet the Soviet Union, the European Space Agency, and Japan are all planning such a venture.

Technically, it is within our means to reestablish U.S. preeminence in space. The civil space program and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration offer a number of options to carry out the purpose and direction of U.S. aeronautics and space activities. These options are examined in this report in full recognition of the need for fiscal restraint in the immediate future.

B. The U.S. Aeronautics and Space Program in 1980

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) was created in 1958 by the National Aeronautics and Space Act (PL 85-568), largely as a response to the launch of Sputnik by the Soviet Union.

The Act declared that it is the policy of the United States that activities in space be developed to peaceful purposes for the benefit of all mankind, and that these activities (except those primarily associated with the defense of the United States) should be the responsibility of a civilian agency. [2] This agency—NASA—was chartered to carry out significant programs in aeronautics, space science, space technology and applications, and manned space flight.

In 1961, the President challenged the nation to land men on the Moon by the end of that decade. The Apollo project not only made the United States preeminent in space technology, but also instilled a sense of pride in the American people. Apollo’s success was due to a long term commitment; adequate and stable financial support; a technological partnership among government, industry and universities; and disciplined managers drawn from within and outside the government.

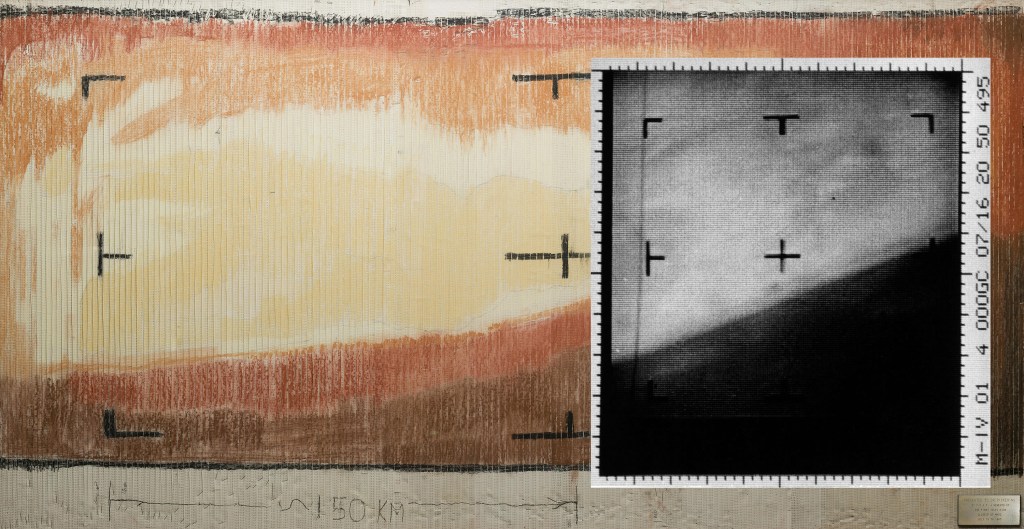

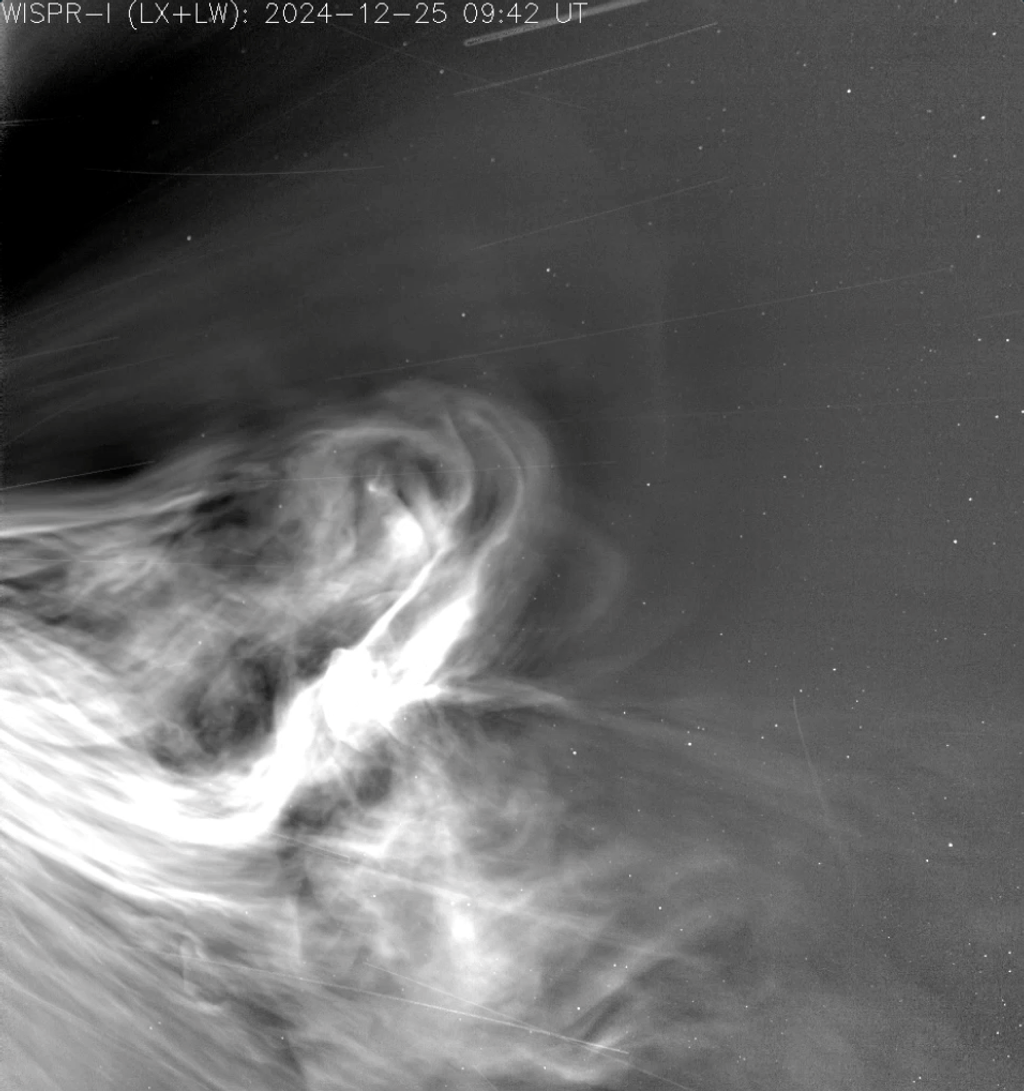

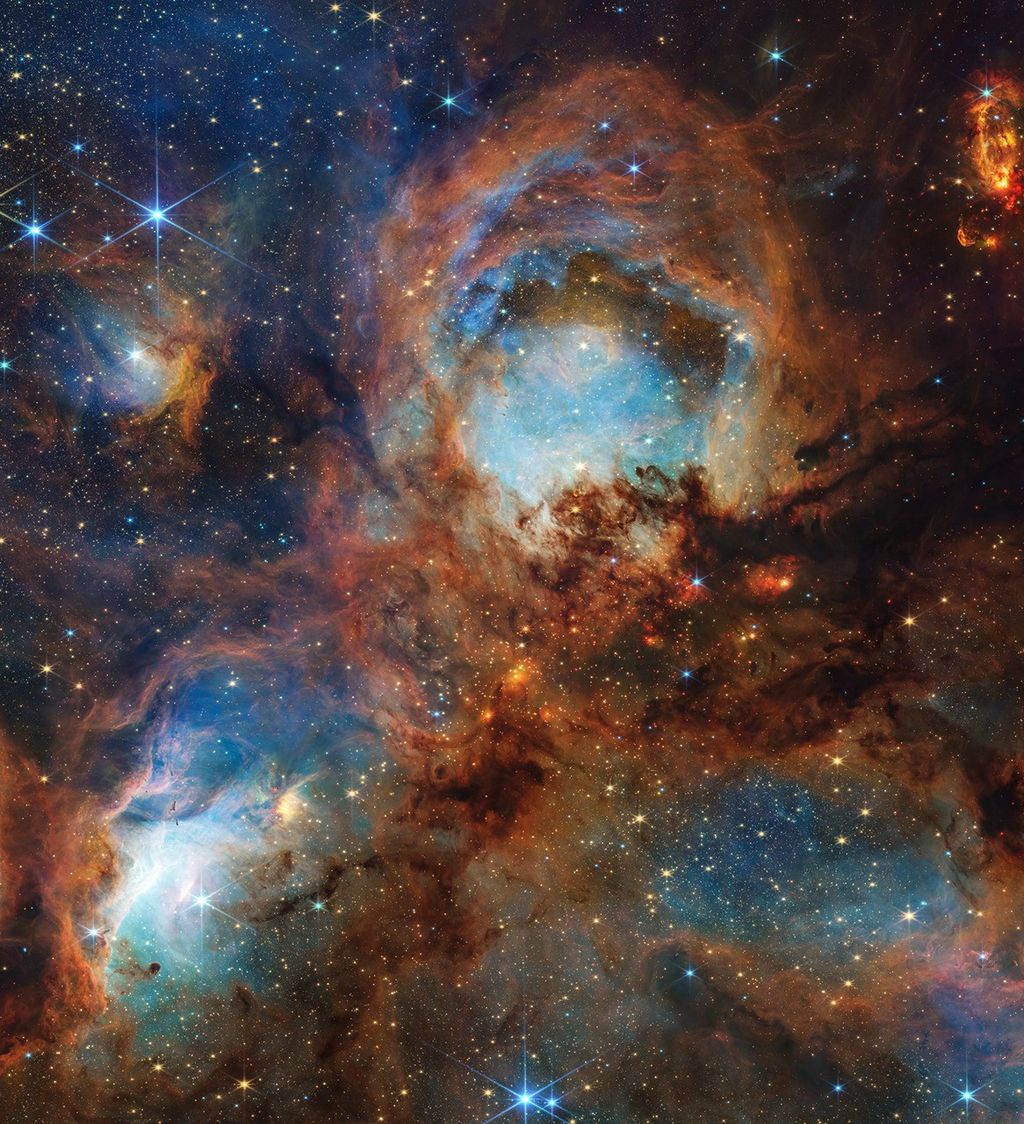

Also in the past two decades, automated spacecraft explored Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn, while telescopes above the earth’s atmosphere gave us new eyes to learn about our universe—the strange world of pulsars, quasars and black holes. The result was a new understanding of the past, present, and future of our total environment.

In the meantime, communications satellites have spawned an entire new industry, weather satellites can warn us of storms, and remote sensing satellites offer tremendous economic potential from assessing and managing the earth’s resources.

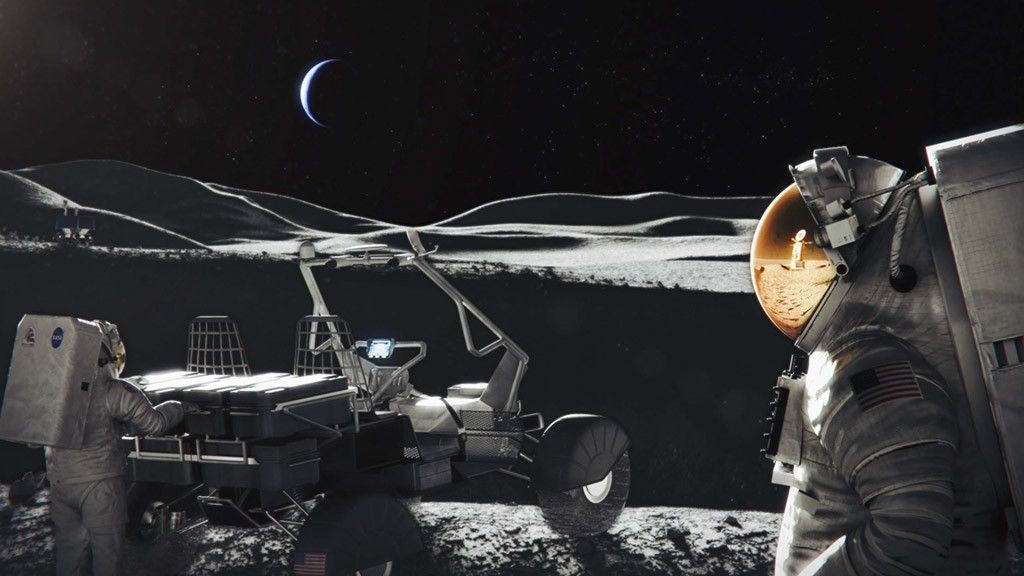

At the end of 1980 we are on the eve of the launch of Columbia, the first Space Shuttle, and its promise to provide a multiplicity of benefits—in science, in exploration, in terrestrial applications, and in the security of our nation—from easy access to this new ocean of space.

C. Aeronautics

Since 1915 NASA (and its predecessor, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics) has been the world leader in aeronautical research. At NASA’s laboratories are many of the national facilities and technical experts necessary to continue progress in the rapidly advancing field of aviation. NASA is also at the focal point of a unique partnership among industry, universities, the Department of Defense, and NASA itself that has been responsible for U.S. preeminence in aeronautics.

Built on the foundation of this research and technology base, the U.S. aviation industry employs about 1,000,000 Americans, ranks second largest among U.S. manufacturing employers, contributes more than any other manufacturing industry to the U.S. balance of trade, and has replaced agriculture as first in net trade contribution.

Continued advancements in research and technology are essential if the U.S. aviation industry is to remain a viable competitor in the world market.

D. The Space Program and U.S. Policy

In recent years the United States has lost its competitive edge in the world, militarily, commercially, and economically, [3] and our competition with the Soviet Union has taken on a new dimension.

The Soviet Union recognizes that science and technology are major factors in that competition. The nation that is strong in science and technology has the foundation to be strong in all other areas and will be perceived as a world leader.

Aeronautics and space can be major factors in our technological strength. They demand the very best in engineering, because the consequences of mistakes are great: the crash of an aircraft, or the complete failure of a spaceship.

A viable aviation industry and a strong space program are important visible elements in our international competition. Beyond these fundamental points, the United States civil space program, unlike many other government programs and agencies, has significant actual and potential impact on U.S. policy. Although some elements of the program have been so utilized, their potential in U.S. policy remains largely unrecognized and unrealized. The major factors are as follows:

1. National Pride and Prestige

National pride is how we view ourselves. Without a national sense of purpose and identity, national pride ebbs and flows in accordance with short-term events. The Iranian hostage situation and the abortive rescue mission have done harm to our national pride quite out of proportion to our true abilities as a nation. On the other hand, the recent Voyager visit to Saturn, reported by an enthusiastic press, made a significant contribution to our sense of self-worth. The space program has characteristics of American historic self-image: a sense of purpose; a pioneering spirit of exploration, discovery, and adventure; a challenge of frontiers and goals; a recognition of individual contributions and team efforts; and a firm sense of innovation and leadership.

National prestige is how others view us, the global perception of this country’s intellectual, scientific, technological, and organizational capabilities. In recent history, the space program has been the unique positive factor in this regard. The Apollo exploration of the Moon restored our image in the post-Sputnik years, and the Voyager exploration of Saturn was a bright spot in an otherwise gloomy period of dwindling world recognition. With space programs we are a nation of the present and the future, while in the eyes of the world we become outward and forward looking.

2. Economics and Space Technology

A vigorous space program has provided many technological challenges to our nation. Efforts such as Apollo, Voyager, and the Space Shuttle have involved challenges and risks far more significant than those of short-term technological needs.

Meeting these challenges has resulted in a “technological push” to American industry, fostering significant innovation in [4] a wide range of high technology fields such as electronics, computers, science, aviation, communications and biomedicine. The return on the space investment is higher productivity, and greater competitiveness in the world market.

The space program also returns direct dividends, as in the field of satellite communications. The potential economic returns from satellite exploration for earth’s resources are great.

3. Scientific Knowledge and Inspiration for the Nation’s Youth

U.S. leadership in the scientific exploration of space has provided new knowledge about the earth and the universe, thus forming the basis for applied research and development—a significant factor in our society and economy.

The exploration of space has provided an inspirational focus for large numbers of young people who have become students of engineering and science. At a time when there is a shortage of technically trained people, when the U.S. productive vitality depends on the application of science, the space program could help attract young people into these fields.

4. Relation to U.S. Foreign Policy

Aspects of the civil space program can serve as instruments to develop and further U.S. foreign policy objectives. Not only can the space program contribute to how this country is viewed in the eyes of the world, but cooperative space activities, such as the U.S.-U.S.S.R. Apollo-Soyuz mission and European Space Agency payloads on the Space Shuttle, are important to other countries. Technology associated with the space program has resulted in strong economic and technological interaction with developed countries, as well as in important aid to underdeveloped countries, particularly in the areas of communications and resource exploration.

E. Observations

At the end of 1980 the U.S. civil space program stands at a crossroads. The United States has invested in a great capability for space exploration and applications, a capability that provides benefits in national pride and prestige, in science and technology, in the inspiration of young people, in foreign policy, and in economic gain.

Now this capability is waning. NASA and the space program are without clear purpose or direction. . . .

[39]

VI. Summary of Recommendations

NASA represents an important investment by the United States in aeronautics and space. The agency’s programs have provided, and continue to offer, benefits in science and technology, in national pride and prestige, in foreign policy, and in economic gain. However, in recent years the agency has been underfunded, without purpose or direction. The new administration finds NASA at a crossroads, with possible moves toward either retrenchment or growth. The transition team has examined ten major areas and various options for dealing with them. For each issue, the team has made recommendations as follows:

A. Presidential statement of purpose of the U.S. civil space program [pages 5–7]

It is recommended:

- That the President recognize the importance of the U.S. space program at an early date (e.g., the inaugural address) without yet making a commitment.

- That the purpose and direction of the U.S. space effort be defined, and that a commitment to a viable space program be articulated by the President at a timely opportunity, such as the first flight of the Shuttle in the spring of 1981. (N.B. A viable space program could be smaller than, equal to, or larger than the present one, but it must have purpose and direction.)

B. NASA as an organization [pages 8–11]

- The NASA Administrator

It is recommended that the President select a politically experienced and strong manager as NASA Administrator, that he reestablish the Administrator’s role as that of principal advisor on civil space matters, and that he be accessible to the Administrator as necessary. - Management capability

It is recommended that the Administrator, working either within the agency or with an outside group, assess NASA’s vitality and discipline in management of complex projects, and make changes necessary to effect improvements. - Staffing

It is recommended that the dual problem of bringing experienced people from industry into government, and of [40] attracting bright young engineers and scientists into government service be addressed immediately, for the government as a whole and for NASA in particular. - The size of NASA

It is recommended that the question of whether or not NASA needs all its field centers be addressed as soon as the purpose of the aeronautics and space program is defined.

C. Space policy and conflict resolution [pages 12–16]

It is recommended that space policy development and conflict resolution be assigned to the NASA Administrator or special ad hoc groups as the need arises; and that consideration be given to a permanent space policy board for this purpose.

D. The civil space program and national policy [pages 14–15]

It is recommended that the administration develop an unequivocal statement of national space policy and an organizational framework that promotes economic exploitation of our capabilities and uses space to further our international goals.

In the area of remote sensing, the administration should undertake the development of an integrated civil program.

In foreign policy, the administration should develop procedures for the Department of State and other government agencies, together with industry, to employ space technology to further foreign policy objectives.

E. Space Shuttle flight readiness [pages 16–17)

It is recommended that:

- The NASA Administrator schedule immediate briefings and reviews, with NASA and contractor personnel, to become familiar with the Shuttle and its problems.

- The Administrator obtain a formal assessment of Shuttle readiness from the Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel.

- The Administrator seek the advice (outside the regular review process), of the knowledgeable outside experts.

- The Administrator and/or Deputy participate in scheduled reviews and make specified Flight Readiness Firing and Launch decisions.

[41] F. U.S. space launch capability [pages 18–19]

It is recommended:

- That existing plans for initial Shuttle operations, retention of expendable launch vehicles for the time being, and transfer of payloads to the Shuttle, be allowed to stand.

- That at an appropriate time after the first flight (or flights) of the Shuttle, the President direct the Administrator of NASA to address the issues of Shuttle enhancement, continued Shuttle production, and expendable launch vehicle production; and to resolve them in the best interest of the United States, taking into account all users—commercial, civilian, government, DOD, and foreign.

G. The transfer from research and development to operations [pages 20–22]

It is recommended:

- That the question of operational management of remote sensing satellite systems be addressed on an urgent basis (see section on “The Civil Space Program and National Policy”).

- That consideration be given to turning the operation of expendable launch vehicles over to a government agency other than NASA or to a private commercial organization in the next year.

- That long term Space Shuttle operations be addressed only after some flight experience with the Shuttle is in hand.

H. Aeronautics [pages 23–24]

It is recommended that NASA’s traditional role of research and technology support to civil and military aviation be reaffirmed, and perhaps even strengthened, to help stem the loss of U.S. leadership in aviation.

I. NASA’s role in areas other than aeronautics and space [pages 25–26]

It is recommended that NASA’s future role in non-aeronautics and non-space activities be confined to assistance to other agencies as requested for limited periods of time only, using cost reimbursements as possible, and that current long term commitments in other areas be eventually moved from NASA.

[42] J. Personnel [pages 27–30]

It is recommended that the new NASA Administrator review the situation of reemployed annuitants at an early date with the view of terminating the employment of many of them. …