Soon after the opening of the Space Age, both the Soviet Union and the United States set their sights on the Moon as a target for exploration by robotic spacecraft. In March 1958, the Soviet Union approved the development of one series of spacecraft to impact the Moon’s surface and another to photograph the Moon’s hidden far side during a flyby. That same month, the United States announced the development of a series of Pioneer spacecraft to study the Moon with orbiter and flyby missions.

The first three Soviet attempts to reach the Moon in 1958 ended in launch failures caused by various anomalies with the R-7 rocket. On Jan. 2, 1959, the Soviet Union announced the launch of their first Cosmic Rocket (retroactively renamed Luna 1 in 1963), carrying a 796-pound spherical spacecraft containing six scientific experiments to monitor space radiation, magnetic fields, and micrometeorite impacts. The rocket’s new upper stage provided the thrust needed to achieve escape velocity, sending the spacecraft on a trajectory toward the Moon. However, the upper stage fired longer than planned, and the probe missed the Moon by about 4,000 miles 34 hours after launch. On the way to the Moon, the upper stage released one kilogram of sodium gas at a distance of 74,000 miles, creating a cloud that Soviet ground-based astronomers were able to photograph. Ground controllers maintained contact with Luna 1 until about 62 hours after launch when its batteries were drained, at which point it was 370,000 miles from Earth and had already become the first spacecraft to enter solar orbit.

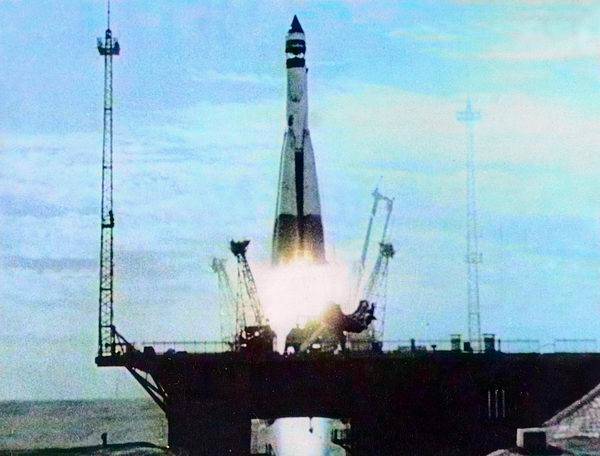

Left: Launch of a Luna spacecraft in 1959. Right: Luna 1 shown attached to its upper stage.

Credits: RKK Energiya.

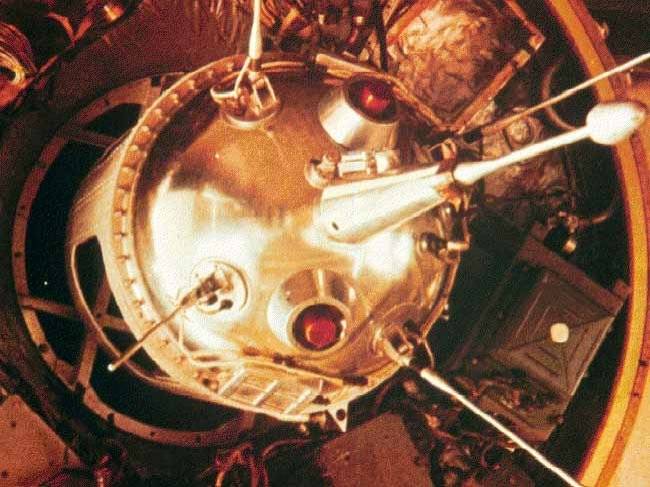

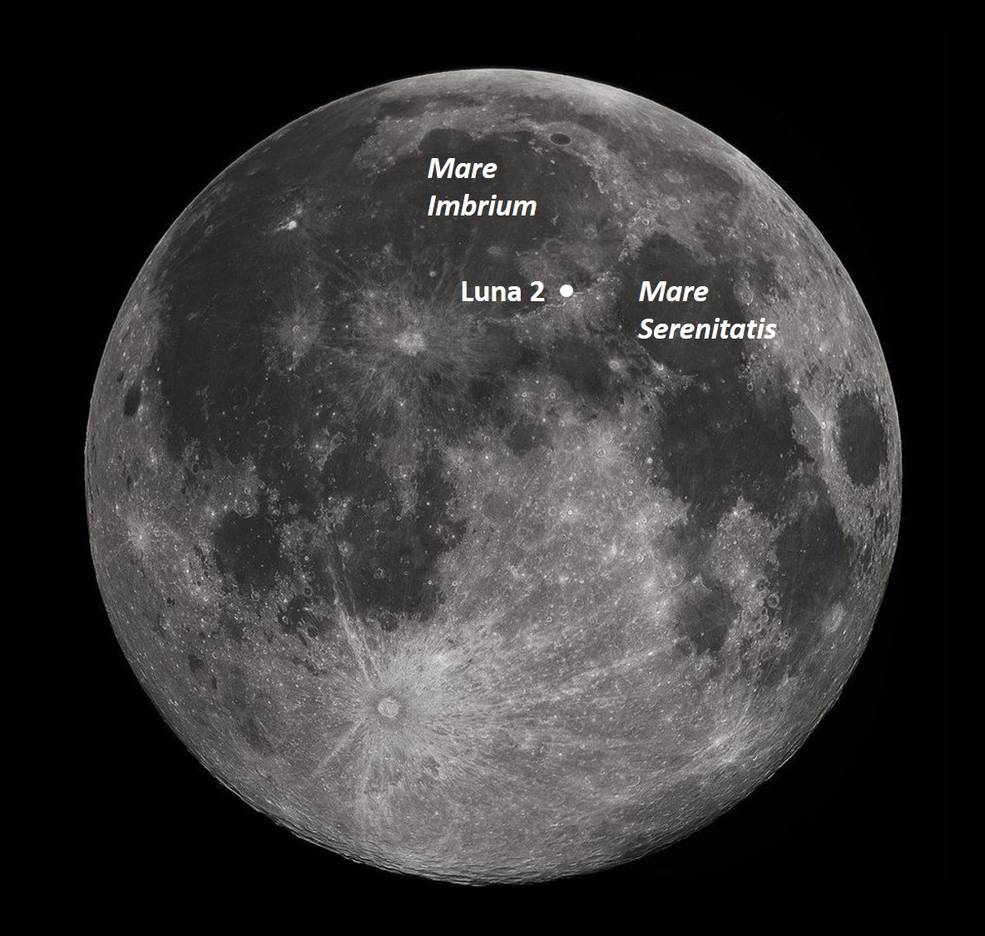

Following another launch failure in June 1959, the Soviets launched their second Cosmic Rocket (later renamed Luna 2) on Sep. 12 and it successfully achieved escape velocity and placed the spacecraft, virtually identical to Luna 1, on an intercept course with the Moon. The upper stage once again released its one kilogram of sodium gas at a distance of 97,000 miles. On Sep. 13, Luna 2 became the first spacecraft to make contact with another celestial body when it impacted the Moon between Mare Imbrium and Mare Serenitatis, about 160 miles from where Apollo 15 would land 12 years later. The spacecraft’s scientific instruments detected no magnetic field or radiation belts around the Moon. Luna 2 deposited Soviet emblems on the lunar surface, carried in two metallic spheres. During his only visit to the United States a few days after the Luna 2 mission, Soviet Premier Nikita S. Khrushchev presented a replica of the spherical pennant to President Dwight D. Eisenhower. That sphere is kept at the Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum in Abilene, Kansas, while a copy is displayed at the Kansas Cosmosphere in Hutchinson, Kansas.

Left: Photograph of the Moon showing the site where Luna 2 crashed.

Right: A model of the sphere with Soviet pennants carried by Luna 2.

Credits: Kansas Cosmosphere.

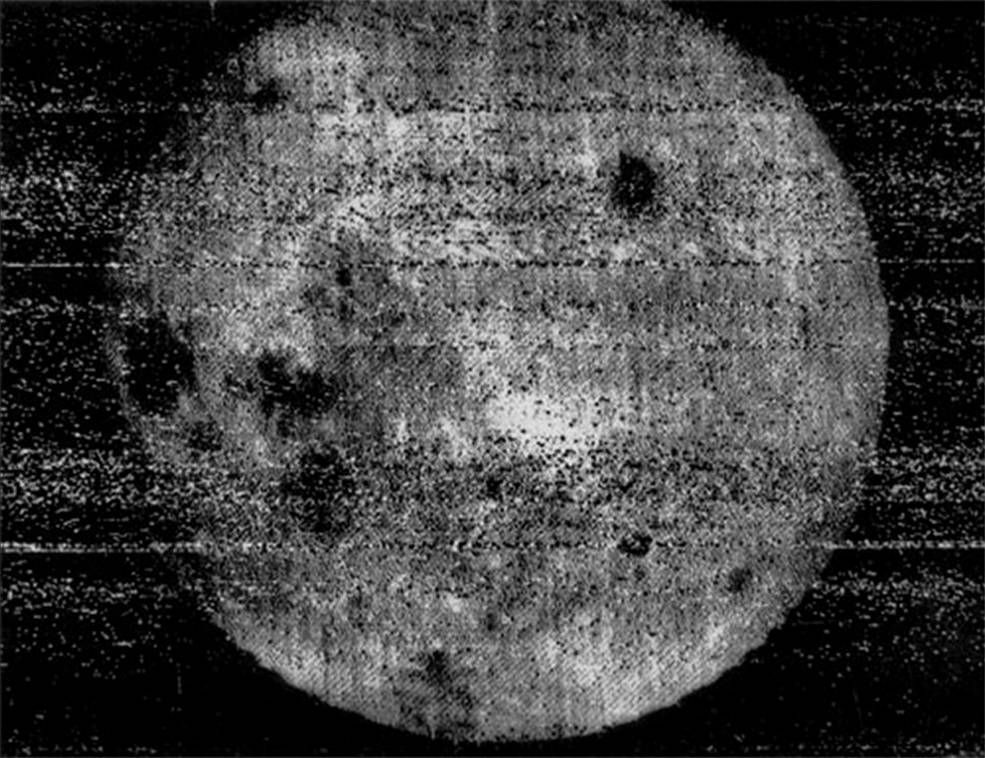

The Soviets had better luck with the photography mission, achieving success on their first attempt. They launched the Automatic Interplanetary Station (later renamed Luna 3) on Oct. 4, 1959. In addition to its photographic imaging system, Luna 3 carried five instruments to measure radiation levels and micrometeorite impacts. On Oct, 6, the spacecraft passed over the Moon’s southern polar region at an altitude of 4,900 miles before looping behind the Moon. The next day, at a distance of 40,500 miles, Luna 3 began taking 29 photographs of the Moon’s far side, the entire session taking about 40 minutes. The film was developed onboard the spacecraft and scanned much like a facsimile before the images were transmitted to Earth. Luna 3 photographed about 70% of the Moon’s far side, and although the image quality was rather poor, the pictures revealed a distinctly different appearance than the Earth-facing side, with far fewer maria. After the end of Cold War, declassified documents revealed that Luna 3 had used unexposed film from a CIA reconnaissance balloon that had drifted over Soviet territory and had been recovered and stored at a Soviet military academy. Soviet scientists had determined that the temperature-resistant and radiation-hardened film was ideal for spaceflight use and repurposed it for the Luna 3 mission.

Left: A model of the Luna 3 spacecraft. Right: One of the first photographs of the Moon’s far side returned by Luna 3.

Credits: Memorial Museum of Astronautics, RKK Energiya.

The United States’ Pioneer program consisted of five probes – the first three were planned as lunar orbiters and the last two involved simpler lunar fly-by spacecraft. The first launch attempt on Aug. 17, 1958, ended in failure 77 seconds after liftoff when the rocket’s first stage exploded. The problem with the booster was identified and corrected and on Oct. 11 the 84-pound Pioneer 1 thundered off its launch pad at Cape Canaveral, Florida. Liftoff seemed to go well, but tracking soon showed that the spacecraft was traveling too slowly and was also off course. Relatively minor errors in the first stage’s performance were compounded by problems with the second stage, preventing Pioneer 1 from achieving its primary goal of entering orbit around the Moon. The spacecraft did reach a then-record altitude of 70,770 miles about 21 hours after launch before beginning its fall back to Earth. It burned up on reentry over the Pacific Ocean 43 hours after liftoff. The probe’s instruments confirmed the existence of the Van Allen radiation belts discovered by Explorer 1 earlier in the year.

Left: A replica of the Pioneer 1 spacecraft. Right: Liftoff of Pioneer 1, the first satellite launched by NASA.

Credits: NASM.

The third and final lunar orbiter attempt, Pioneer 2 on Nov. 8, met with less success. The rocket’s first and second stages performed well, but the third stage failed to ignite. Pioneer 2 could not achieve orbital velocity and reached a peak altitude of only 960 miles before falling back to Earth after a brief 42-minute flight.

The two lunar flyby missions followed, with the 13-pound Pioneer 3 taking off on Dec. 6. The rocket’s first stage engine cut off early, and the probe was not able to reach its destination, falling back to Earth 38 hours after launch. Despite this problem, Pioneer 3 returned significant radiation data and discovered a second outer Van Allen belt encircling the Earth. The second attempt on March 3, 1959, was more successful and Pioneer 4 passed within 36,650 miles of the Moon’s surface. It then went on to become the first American spacecraft to enter solar orbit, just two months after Luna 1 accomplished that feat. Pioneer 4 returned radiation data for 82 hours, out to 409,000 miles, nearly twice the Earth-Moon distance.

Left: Pioneer 3 lunar flyby spacecraft under construction at JPL.

Right: Launch of Pioneer 4, the first American spacecraft to enter solar orbit.

Although these early Pioneer lunar probes met with limited mission success, the program marked the first use of the 26-meter antenna and tracking station at Goldstone, California. This antenna, completed in 1958 and known as Deep Space Station 11 (DSS-11), was the first component of what eventually became the NASA Deep Space Network (DSN). DSS-11 not only followed these early Pioneers, starting with Pioneer 3, but later monitored the Surveyor lunar soft landers and tracked the Apollo 11 Lunar Module Eagle to the Moon’s surface on July 20, 1969.

After these initial efforts, both the Soviet Union and the United States took a hiatus in their lunar exploration programs. The Soviets began the development of their next phase of lunar landers and orbiters in their Luna program while the United States began preparations first for the Ranger program of imaging spacecraft, followed by the Surveyor series of softlanders and Lunar Orbiters to map the lunar surface to look for landing sites for the first human landings of the Apollo Program.