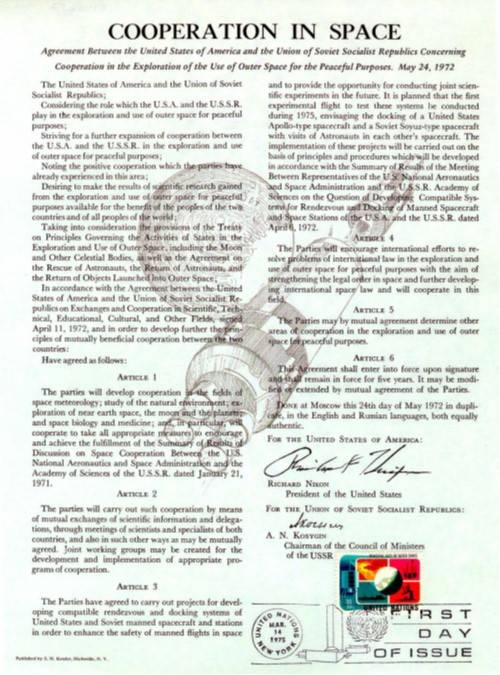

During the 1960s, collaboration in the space arena between the United States and the Soviet Union remained at a low level, the relationship characterized more by competition than cooperation. In the climate of détente in the early 1970s, the two nations began discussions to develop a common docking system. On May 24, 1972, during their summit meeting in Moscow, the leaders of the United States and the Soviet Union, President Richard M. Nixon and Premier Aleksei N. Kosygin, signed an agreement on cooperation in space. One of its articles called for the development of a joint system to allow their spacecraft to dock with each other in orbit, laying the groundwork for the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, the first international human spaceflight carried out in July 1975.

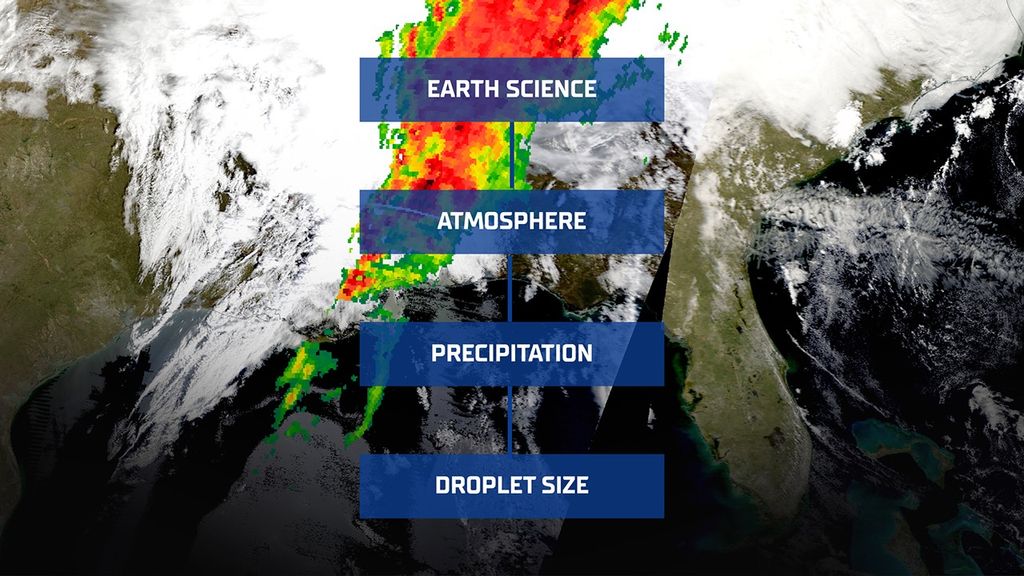

Left: At the summit meeting in Moscow in May 1972, U.S. President Richard M. Nixon,

left, and Soviet Premier Aleksei N. Kosygin sign the agreement on space cooperation

that led to the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project. Right: The agreement on space

cooperation signed at the May 1972 Moscow summit.

The “Agreement Concerning Cooperation in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space for Peaceful Purposes,” signed in Moscow in May 1972, followed a decade of lower-level collaborative efforts between the two space powers and two years of detailed discussions on a common docking system. After astronaut John H. Glenn’s successful orbital flight in February 1962, President John F. Kennedy of the United States and Premier Nikita S. Khrushchev of the Soviet Union exchanged letters exploring the possibility for cooperation in space. The next month, NASA Deputy Administrator Hugh L. Dryden and Anatoli A. Blagonravov of the Soviet Academy of Sciences met at the U.S. mission to the United Nations in New York for the first in a series of discussions about possible future collaboration in space between the two nations. These discussions led to an agreement for joint scientific studies of the Earth and in space biology and medicine. Despite these efforts at cooperation, competition to land the first man on the Moon, the goal President Kennedy set for the nation in 1961, prevailed for the remainder of the 1960s. Following the July 1969 Moon landing, several reciprocal astronaut and cosmonaut goodwill tours contributed to a renewed atmosphere of collaboration, encouraged by President Nixon’s policy of détente with the Soviet Union. In October 1970, Robert R. Gilruth, director of the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC), now NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, led a five-person team to the Soviet Union. The joint meetings laid the groundwork for future cooperation, in particular on development of universal docking systems. During their visit, Gilruth and his team toured the Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center in Star City outside Moscow, the first official NASA delegation to do so.

Left: NASA Deputy Administrator Hugh L. Dryden, left, and Anatoli A. Blagonravov

of the Soviet Academy of Sciences during their March 1962 meeting. Right: A NASA

delegation led by director of the Manned Spacecraft Center, now NASA’s Johnson

Space Center in Houston, Robert R. Gilruth, third from right, pose with their

Soviet hosts during their visit to the Cosmonaut Training Center in Star

City in October 1970.

In January 1971, Acting NASA Administrator George M. Low visited the Soviet Academy of Sciences in Moscow with a small delegation, taking the next steps in the discussions to put an actual mission into the plan. Low proposed to the Russians to develop a common docking system for use with Apollo and Soyuz spacecraft in the near future, with consideration being given to a joint mission within the next five years. The two sides also reached agreement on cooperation in other areas, such as exchanging lunar samples and joint work in space biology and medicine. These agreements formed the groundwork for further discussions and for the May 1972 agreement at the Moscow summit.

Left: Joint American-Soviet meeting on space cooperation at the Soviet Academy

of Sciences in Moscow in January 1971. Right: Acting NASA Administrator George

M. Low, left, and Soviet Academician Mstislav V. Keldysh sign the minutes

of the January 1971 meeting.

A 19-person Soviet delegation arrived in Houston in June 1971 for a weeklong series of technical discussions on a common docking system. By the end of the week, the two sides agreed that a joint mission appeared feasible. They considered several options, including a docking between an Apollo and a Soyuz spacecraft that required a docking module to act as an airlock since the two spacecraft used dissimilar atmospheres, between an Apollo and Soviet Salyut space station, and between a Soyuz and a Skylab space station. To emphasize the importance of the joint activity and to expedite future discussions, the American side appointed Glynn S. Lunney as the NASA project director and the Soviets named Konstantin D. Bushuyev of the Academy of Sciences as their project director.

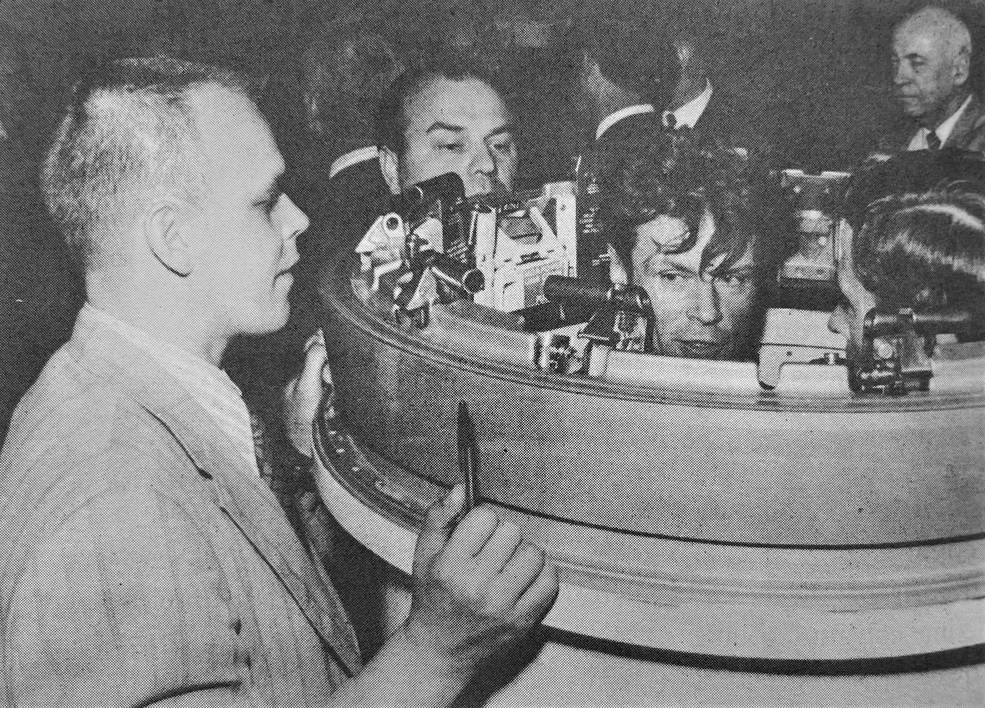

Left: American and Soviet delegates during the June 1971 meeting in Houston on

developing a common docking system. Right: During the meeting in Houston,

Soviet docking system expert Vladimir S. Syromyatnikov, left, and NASA

astronaut John W. Young inside an Apollo Command Module docking ring,

inspecting its components.

In the months leading up to the next face-to-face meeting in Moscow in November 1971, both sides developed concepts needed for the joint mission. The American side contracted with North American Rockwell in Downey, California, the builder of the Apollo spacecraft, to design a docking module to act as an interface and airlock between the two spacecraft to allow crew member exchanges. The Soviets developed a proposal for an androgynous docking system, designed by Vladimir S. Syromyatnikov, that could be used for the joint mission and applied to future projects as well. A derivative version of this system is still in use on the International Space Station today. Gilruth and Lunney arrived in Moscow in late November, leading a 20-person delegation for the weeklong series of meetings. The teams broke into working groups to address specific aspects of the joint mission and prepared a timeline of activities required to achieve the flight in mid-1975.

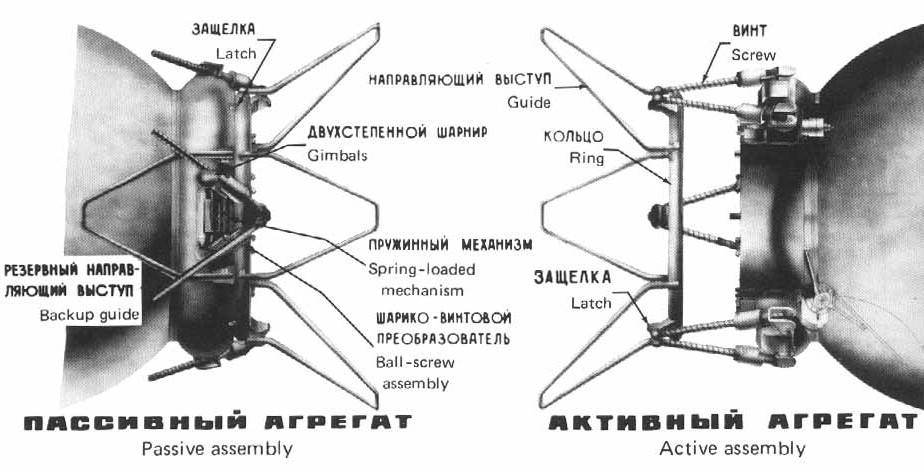

Left: The Soviet proposal for a universal docking system, presented during the

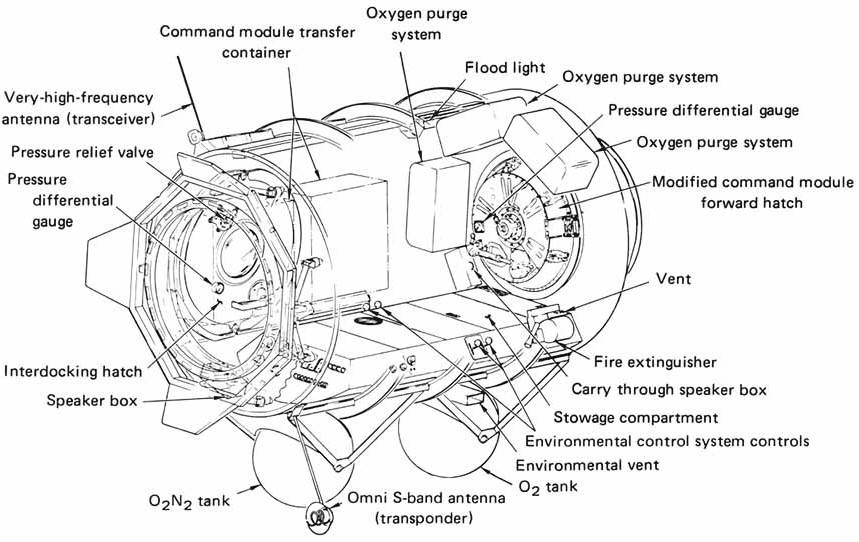

November 1971 joint meeting in Moscow. Right: The American proposal for a

docking module, presented during the November 1971 meeting.

Following further meetings and teleconferences between the two sides to iron out technical issues, Low and Lunney traveled to Moscow in early April 1972, to reach agreement on the management structure of the joint project. The American side accepted the Soviets’ request that the mission involve a docking between an Apollo and a Soyuz spacecraft and not involve a more complex mission to a Salyut space station. The agreements signed by the two sides on April 6 paved the way for inclusion of the joint space mission into the May 1972 summit meeting agenda. On June 30, 1972, the first international human spaceflight officially became known as the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project.

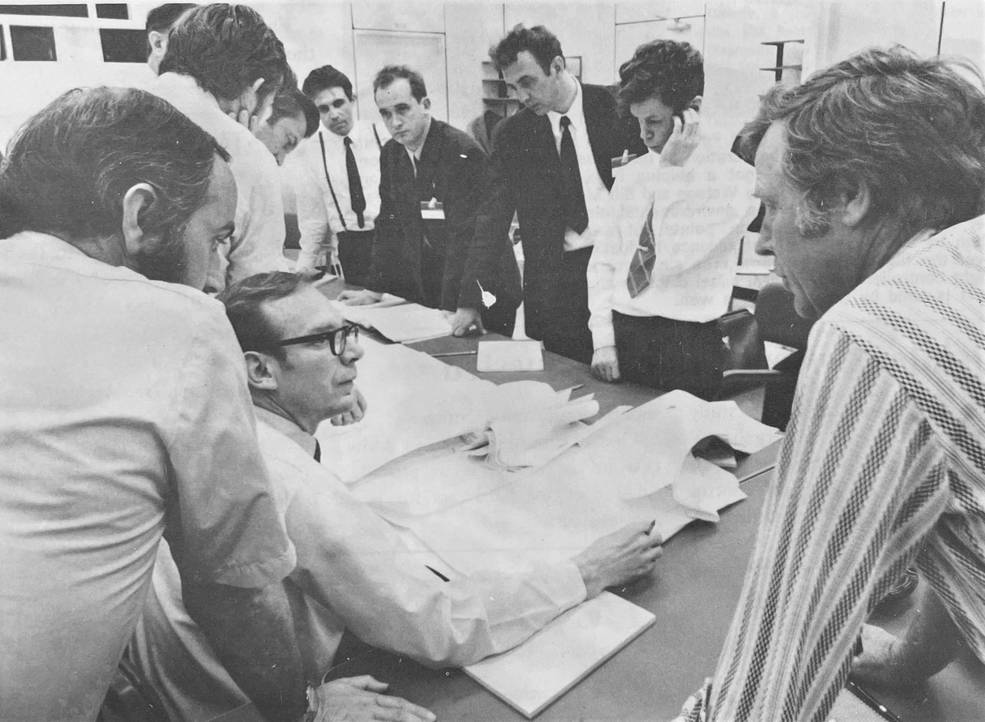

Left: In March 1972, American and Soviet engineers discuss a common docking system

at the Manned Spacecraft Center, now NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston.

Right: During their June 1972 visit to the White House, Apollo 16 astronaut

Charles M. Duke, left, NASA Administrator James C. Fletcher, and Apollo 16

astronauts John W. Young and Thomas K. “Ken” Mattingly show a model of

the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project to President Richard M. Nixon, center.