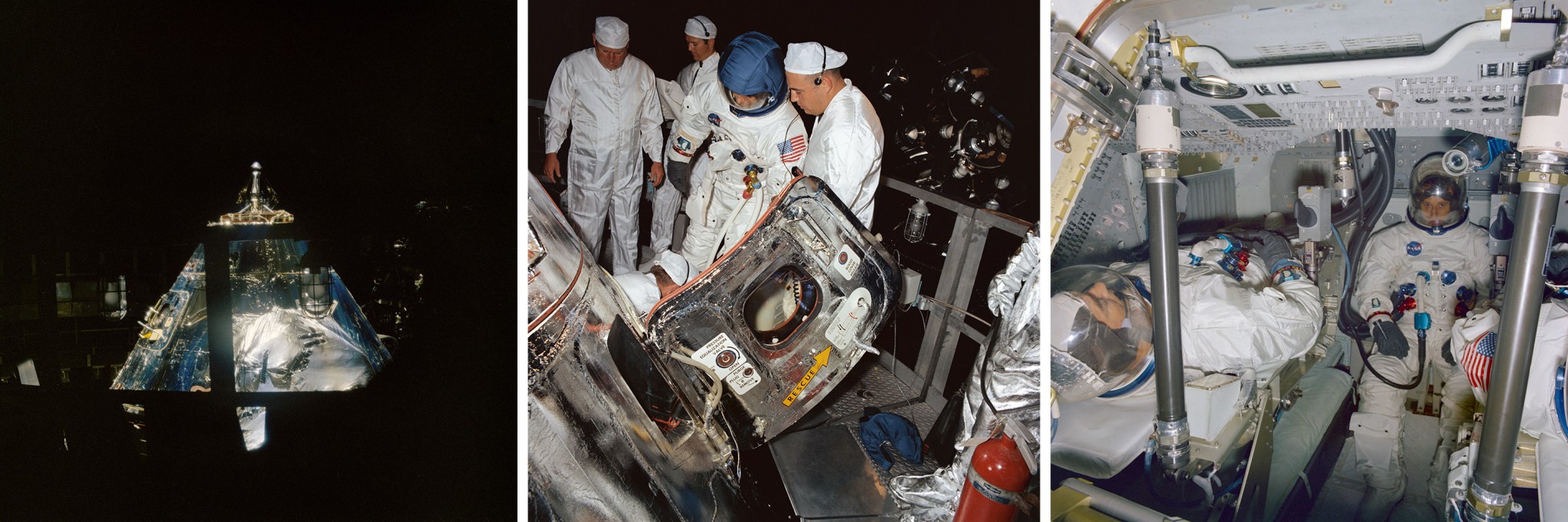

To certify components of the Apollo spacecraft for human spaceflight, NASA carried out several critical tests in 1968 at the Space Environment Simulation Laboratory (SESL) at the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC), now the Johnson Space Center in Houston. Completed in 1965, the SESL houses two chambers for thermal vacuum testing of large spacecraft. The smaller Chamber B was the site of crewed thermal vacuum tests of the Lunar Module (LM), using LM Test Article (LTA) 8, in May 1968. At the time, the larger Chamber A was a 120-foot high, 65-foot diameter stainless steel vessel and could simulate pressures and temperatures equivalent to 130 miles above the Earth. Three astronauts spent a week in June 1968 certifying the 2TV-1 Command and Service Module (CSM) in Chamber A in preparation for Apollo 7, the first Earth orbital crewed flight of the Apollo spacecraft.

Following completion of the June test, engineers modified the spacecraft while still in the chamber to a configuration to match that intended for future lunar flights. These modifications included replacing the older version side hatch with an easier to open unified lightweight version, installing a docking probe to the forward tunnel (which on lunar flights would be used to dock with the Lunar Module), and installing a high-gain steerable antenna (needed for communications at lunar distances). NASA selected three U.S. Air Force personnel assigned to the MSC’s Flight Crew Support Division – Majors Turnage R. Lindsey, Lloyd Reeder, and Alfred H. Davidson – to conduct this round of tests. They completed a two-day checkout in late August to verify test procedures and spacecraft systems prior to the five-day thermal vacuum test.

On September 4, the three men donned spacesuits, entered the spacecraft, and closed the side hatch. Engineers pumped down Chamber A to a vacuum equivalent to roughly 100 miles altitude and maintained that level for most of the test. On the second day, the crew depressurized the spacecraft and opened the side hatch, keeping it open for about two and a half hours to simulate a spacewalk or Extravehicular Activity. After closing the hatch, and repressurizing the spacecraft, the crew removed their spacesuits for the remainder of the test. Engineers modulated the temperature outside the spacecraft between 150o above zero, using carbon-arc lamps to simulate solar heating, and 150o below zero, by flowing liquid nitrogen in the chamber walls to simulate the cold of space.

At the end of the 125-hour test, Lindsey, Reeder, and Davidson emerged from the spacecraft and the chamber and were pronounced in excellent condition. The spacecraft performed well and the five-day test met all planned objectives, certifying the Apollo CSM for lunar missions. As a result of the test and crew recommendations, NASA made several changes to future Apollo spacecraft and operations, such as redesign of some spacecraft thermal blankets and development of passive thermal control attitudes, changes in food packaging and storage, and improvements in the ground network and vehicle communications system. By certifying the Apollo spacecraft for lunar missions, the test brought the Moon landing one step closer.

Read James McLane’s and Robert Wren’s recollections of the SESL from their oral histories with the JSC History Office.