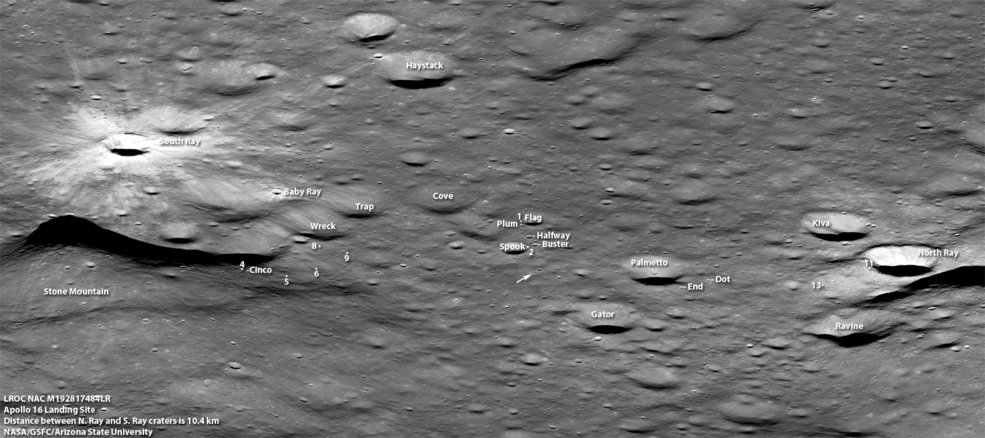

On April 23, 1972, following three days exploring the Descartes highlands site on the Moon, Apollo 16 astronauts John W. Young and Charles M. Duke lifted off aboard the Lunar Module (LM) Orion to rejoin Thomas K. “Ken” Mattingly, who had been conducting science from lunar orbit aboard the Command Module (CM) Casper to characterize the Moon’s surface and environment. Part of that science included deploying a scientific satellite into lunar orbit shortly before the astronauts began their trip back to Earth. During the three-day voyage home, Mattingly conducted the longest deep-space spacewalk to retrieve film canisters from cameras located in the spacecraft’s Service Module. The astronauts held an inflight press conference to provide their views of the mission for reporters, and prepared their spacecraft for reentry and splashdown.

An oblique view of the Apollo 16 landing site at Descartes taken by the Lunar

Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera in 2012, annotated to point out features

visited by astronauts John W. Young and Charles M. Duke during

their explorations.

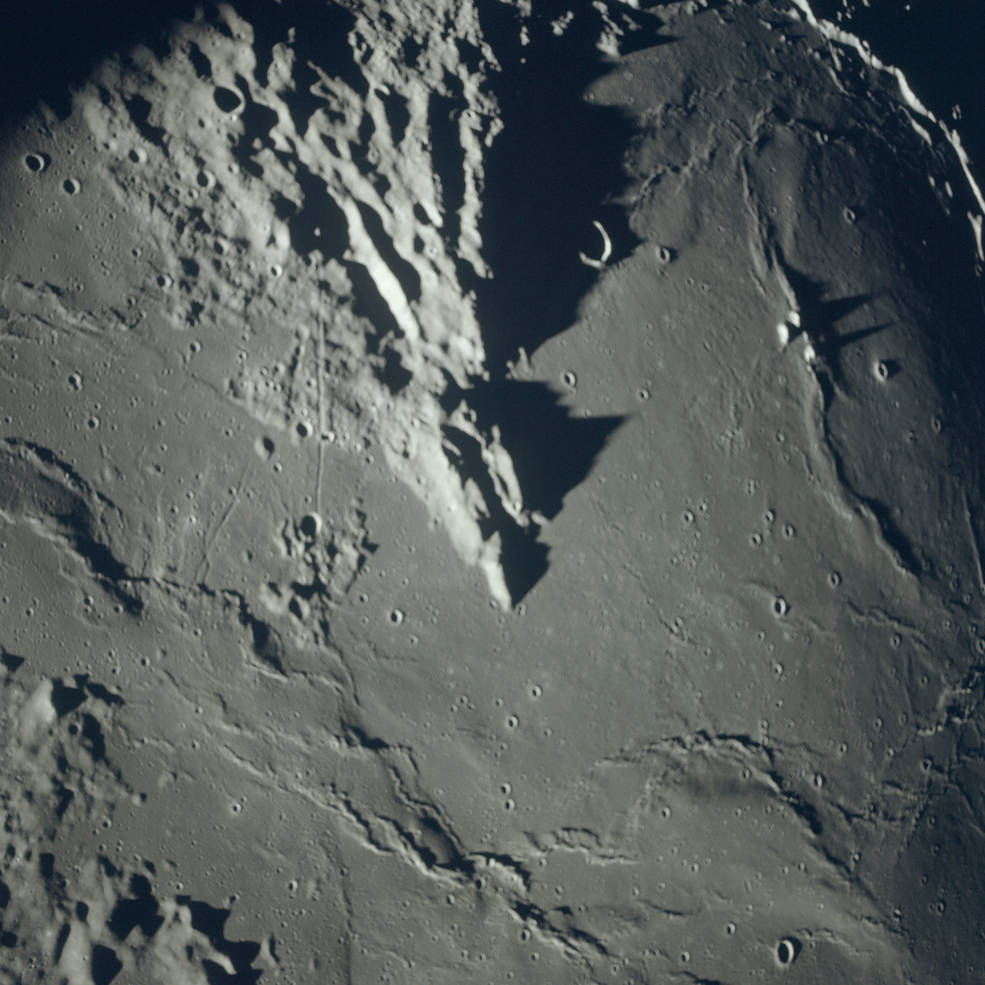

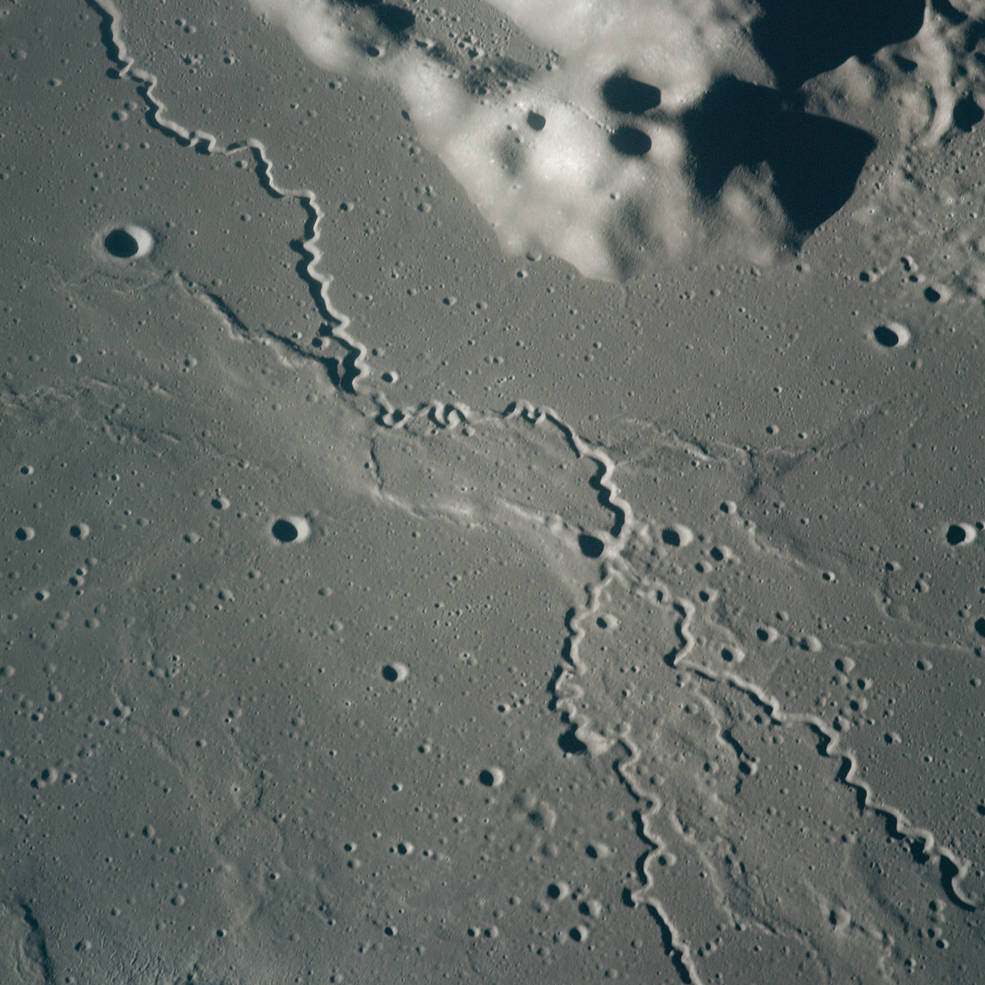

During the three days that Young and Duke explored the lunar surface, Mattingly kept busy in lunar orbit managing the Scientific Instrument Module (SIM) bay experiments and cameras. During his 37 solo revolutions around the Moon, he photographed the lunar surface – both the nearside and the less well-documented farside – mapped the chemical composition of the lunar surface using X-ray and gamma-ray spectrometers, mapped the overall geometry of the Moon, and measured the tenuous lunar atmosphere. Precise tracking of Casper’s orbit allowed better characterization of mass concentrations, or mascons, beneath the lunar surface that cause perturbations in the spacecraft’s trajectory. Mattingly performed an out-of-plane maneuver to align his trajectory for the rendezvous and docking with Orion.

A selection from the hundreds of images that Thomas K. “Ken” Mattingly took of the Moon during his solo lunar orbital flight. Left: The rim of Andel Crater. Middle left: The Riphaen Mountains. Middle right: The southeast rim of the crater Letronne. Right: The Herigonius Rille 1.

Following their exploration of the Descartes highland site, at the end of the third traverse Young and Duke reentered the LM for the final time. They removed their backpacks, overboots, and other unneeded items and jettisoned them out the hatch. In Mission Control at the Manned Spacecraft Center, now NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, Flight Director Eugene F. Kranz ‘s White Team of controllers, including capsule communicator (capcom) James B. Irwin, relieved M.P. “Pete” Frank’s Orange Team and capcom Anthony W. “Tony” England, who had been on duty throughout the final Moonwalk. Young and Duke repressurized the LM and prepared it for liftoff, including stowing all the gear and especially the 209 pounds of lunar samples. During the final stages of liftoff preparations, Mattingly in Casper passed overhead and the three astronauts were able to talk to each other via radio. Young and Duke hot-fire tested the LM’s Reaction Control System (RCS) thrusters, with Duke describing it as, “those beauties rocked this whole spacecraft.”

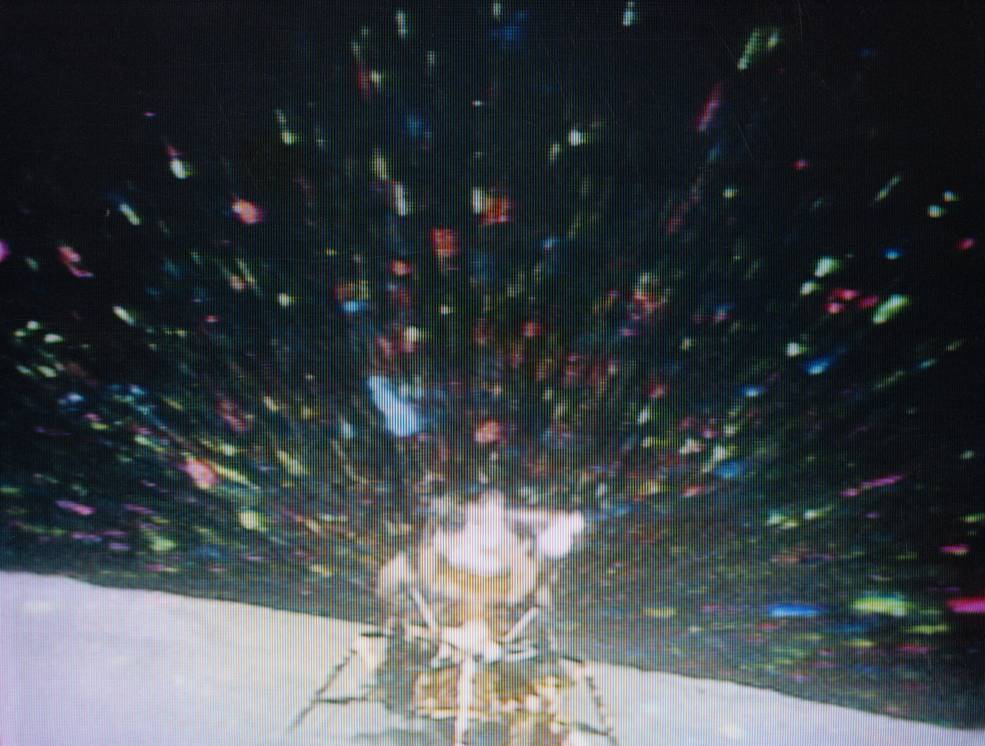

Still images of the liftoff of the Lunar Module Orion, broadcast by the television

camera aboard the Lunar Roving Vehicle (Rover), parked about 300 feet away.

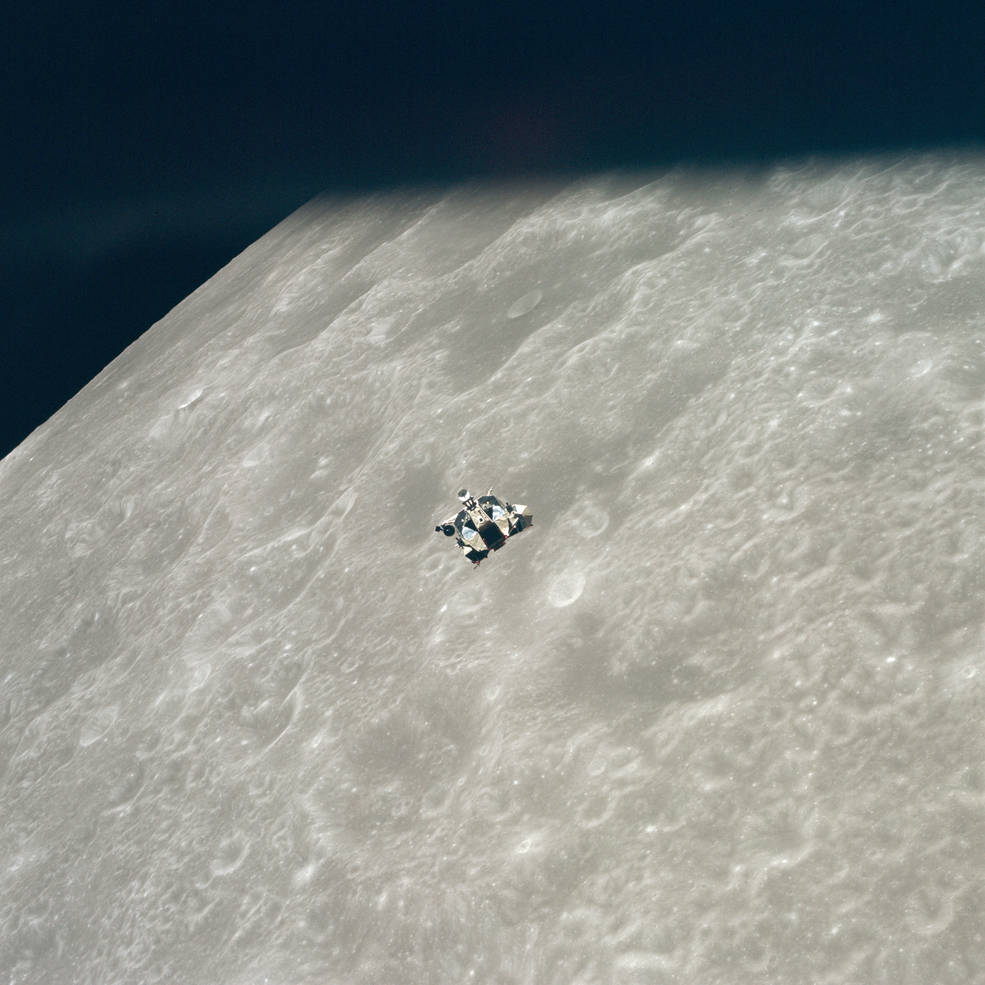

Four hours after Young and Duke entered the LM, Orion ignited its ascent stage engine, with Duke calling out, “Lift-Off. There we go!” Irwin, in Mission Control, replied, “Roger. We saw liftoff,” meaning it literally since Edward I. “Ed” Fendell remotely operated the camera the Rover’s TV camera from Mission Control. Young and Duke’s then-record setting 71-hour, 2-minute lunar surface stay had come to an end. During the ascent, Duke called out, “What a ride! What a ride!” The engine burned for 7 minutes, 7 seconds, cutting off at an altitude of 60,000 feet, delivering Orion and its crew into a 48-by-10-mile orbit. Eight minutes later, Young and Duke caught sight of Casper. As the two spacecraft began station-keeping, Orion performed a 360-degree pirouette so Mattingly could examine and photograph damage to the LM’s external panels that controllers noted from the liftoff footage. Next, Mattingly put Casper through a 360-degree rotation so Young and Duke in Orion could inspect it. The inspections completed, Mattingly brought Casper in for a smooth docking, on the spacecraft’s 53rd revolution around the Moon, ending the two spacecraft’s 81 hours, 28 minutes of independent flight. Young and Duke removed their spacesuits, began to transfer some items to Casper, and powered down Orion. All three astronauts settled down for a good night’s sleep.

Left: The Lunar Module Orion approaching the Command Module Casper.

Middle and right: Mattingly aboard Casper inspects Orion during its

360-degree rotation, noting some damaged external panels.

The following morning, the start of their ninth day in space, Mission Control notified the crew that because of ongoing concerns with the Service Propulsion System’s (SPS) backup controller that caused a six-hour delay in the landing, they decided to have Apollo 16 leave lunar orbit one day early. They also deleted a maneuver to raise their orbit’s altitude. Young and Duke reentered Orion to finish transferring equipment and samples to Casper and putting trash in the LM for jettisoning. The donned their spacesuits, closed the hatches between the two spacecraft, and on Casper’s 62nd revolution, the astronauts jettisoned Orion. Because of a faulty switch setting aboard Orion, it began to tumble shortly after undocking. Mission Control could not control Orion to deorbit it at a pre-selected site, to calibrate the four seismometers now on the Moon. It eventually crashed about one year later. At the end of that revolution, but behind the Moon, the astronauts released the Particle and Fields subsatellite. But because they skipped the maneuver to raise their orbit, the subsatellite entered a lower than planned orbit, and instead of operating for one year, crashed onto the Moon’s farside on May 29, 1972. Mattingly continued his lunar observations until the end of their 64th revolution. While behind the Moon, they fired Casper’s SPS engine for the two-minute, 42-second Trans-Earth Injection maneuver to send them on their way home.

Left: The last Earthrise seen by Apollo 16, shortly after the Trans-Earth Injection

maneuver. Right: During the Apollo 16 trans-Earth coast, astronaut Thomas K.

“Ken” Mattingly, right, retrieves film cassettes from the Scientific Instrument

Module, as Charles M. Duke assists from the Command Module’s hatch.

As they rounded the Moon’s farside, they snapped their last Earthrise photos, and as soon as they reestablished radio contact with Mission Control, Young called, “…just saw you come up like thunder, and that’s how we’re coming up. Just going away from it like – nothing,” referring to how quickly their spacecraft receded from the Moon. He also added that “the boys are all at the windows taking pictures,” and that “morale around here just went up a couple of hundred percent.” From Mission Control, capcom Donald H. Peterson replied, “Morale looks pretty good here, too.” The astronauts’ enthusiasm led them to provide an unscheduled 15-minute TV broadcast to share their views of the Moon, already 9,500 miles distant, with Mission Control. Before going to sleep, they placed their spacecraft into the Passive Thermal Control mode, rotating at three revolutions every hour, to evenly distribute temperatures.

Views of the receding Moon during Apollo 16’s trans-Earth coast.

Shortly after waking up for their 10th day in space, the astronauts passed out of the Moon’s gravitational sphere of influence and began accelerating as the Earth’s stronger gravity began pulling them homeward. At a distance of 211,000 miles from Earth, they performed a minor midcourse correction, a 23-second firing of the Service Module’s RCS thrusters, to refine their reentry trajectory. The trio next donned their spacesuits in preparation for Mattingly’s spacewalk to retrieve film canisters from the SIM-bay instruments. They depressurized Casper, opened the hatch, and Mattingly floated out, installing a TV camera for Mission Control to monitor the spacewalk. Making two trips to the SIM-bay, Mattingly retrieved two large film cassettes and handed them to Duke, floating in the open hatch, who in turn handed them to Young inside the cabin for stowage. Mattingly then installed a microbial sample experiment on a short boom outside the spacecraft, pointing it at the Sun for 10 minutes before retrieving it for return to Earth. Mattingly then reentered the spacecraft and closed the hatch, having spent one hour, 23 minutes outside. Apollo 16 had closed the distance to Earth to 197,000 miles. The rest of their day consisted mainly of housekeeping activities. By the time they began their sleep period, the distance to Earth had closed to 172,000 miles.

At the start of their 11th and last full day in space, Apollo 16 had reached 150,000 miles from Earth and continued to accelerate. Young and Duke held a geology debrief with capcom England, who had also served in that capacity during their three lunar surface excursions, relaying questions from the geology team. Although they conducted further debriefs after their return to Houston, this allowed them to answer questions with their impressions of the surface traverses still fresh. They conducted another session of the light-flash experiment, recording the number of light flashes caused by cosmic rays traversing through their retinas. Later in the day, they held a 20-minute televised press conference, with capcom Henry W. “Hank” Hartsfield reading up 16 questions from reporters. They conducted a Skylab contamination study to evaluate the effects of a water dump on sensitive instruments that the future space station planned to carry. They began stowing items in preparation for the following day’s splashdown. Mission Control informed them that their prime recovery ship the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Ticonderoga had arrived on station in the splashdown zone. When Young, Mattingly, and Duke went to sleep for the last time in space, the Earth was just 90,000 miles away and approaching rapidly.

To be continued…