Introduction

Washington, DC, April 2, 1968. The Uptown Theater. Opening night. The world eagerly awaits the premiere of Stanley Kubrick’s latest epic film. Four years in the making with noted science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke, the film has been delayed and is over budget. Two days later, 2001: A Space Odyssey opens in New York and Los Angeles, and in other US cities the following week. Anticipation runs high, given the talent involved and the near total secrecy surrounding the film during production and editing, which Kubrick was still finishing just a few days before opening day. Even Clarke didn’t see the finished product until the premiere.

The film

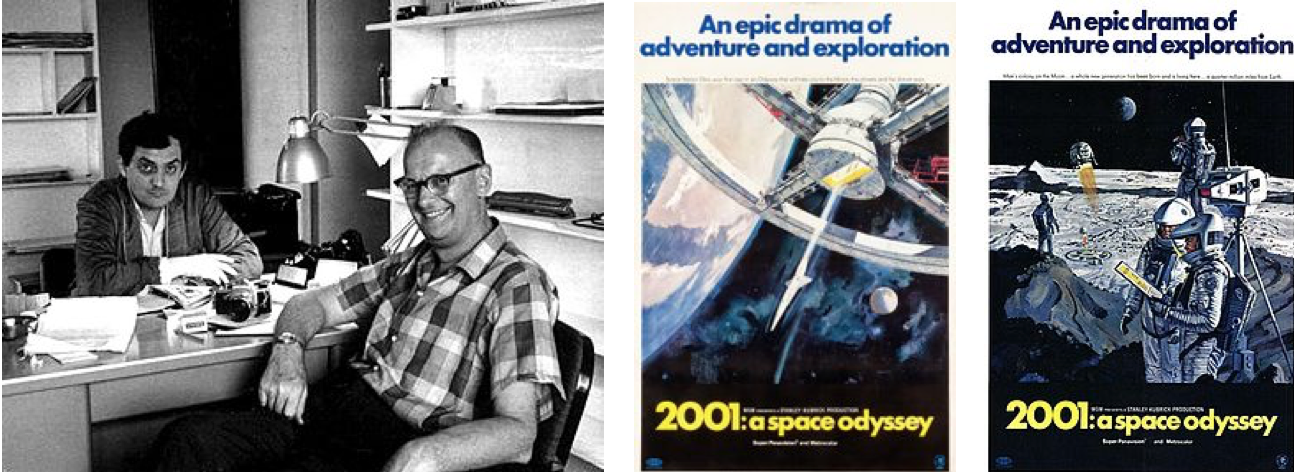

Kubrick and Clarke began collaborating on what would become 2001: A Space Odyssey in April 1964. Using Clarke’s 1951 short story The Sentinel along with other inspirations as source material, the two worked on the film’s screenplay and an accompanying novel in parallel. Kubrick wanted to make the proverbial good science fiction movie that touched on Man’s relationship to the universe. They initially referred to the project as How the Solar System Was Won, while in a February 1965 press release called it Journey Beyond the Stars. Other titles were considered, but Kubrick finally chose 2001: A Space Odyssey, as references to the upcoming millennium and to Homer’s Odyssey. As production proceeded, Kubrick began to realize that he really wanted the film to be primarily a visual (and auditory) rather than a verbal experience. He eliminated, without Clarke’s knowledge, much of the original dialogue and explanatory narration from the screenplay – much of it remains in Clarke’s novel. Indeed, many parts of the film could be considered a silent movie as there is only music – the first and last 20 minutes or so of the film are entirely devoid of dialogue, as are relatively lengthy stretches throughout the film.

His use of classical music such as Johann Strauss’ The Blue Danube and Richard Strauss’ Also sprach Zarathustra for the film was another break from traditional movie production of the time. Kubrick had commissioned Hollywood composer Alex North to compose a custom score for the film but decided against using it. With the exception of one scene, the entire movie was filmed in studios in London, using several innovative film techniques including Cinerama, spacecraft models and a 30-ton centrifuge built especially for 2001 by an aerospace company to rotate the sets required for some of the space flight scenes. The film required 205 special effects sequences, unprecedented at the time, but all before computer generated imagery was invented. One of Kubrick’s struggles was how to represent extraterrestrials so they wouldn’t just look like actors in costume. On the advice of astronomer Carl Sagan, who declared they would look nothing like humans, Kubrick chose to not directly depict aliens, but to represent their intelligence via the recurring theme of the mysterious black monolith.

The film falls into several movements. The first movement, The Dawn of Man, takes place four million years ago. A group of proto-human apes, in the presence of a mysterious black monolith, realize that bones can be used as weapons and take a leap toward gaining human intelligence. In a stunning cinematic transition (a “match cut” in film parlance), a bone is thrown in the air and dissolves into a spacecraft, the story advancing four million years to the next movement. With a stopover at an orbiting space station, a scientist is on his way to the Moon, where an artifact of presumably alien origin, a mysterious black monolith, has been discovered and established to have been deliberately buried there four million years ago. As the Sun hits the monolith, it emits a high pitched noise and the film transitions to the next movement, this time only 18 months in the future, to the Discovery One spacecraft on its way to Jupiter. With three scientists in suspended animation for the duration of the long flight, the spacecraft is essentially controlled by the supposedly infallible HAL 9000 talking computer, with two human astronauts as assistants. The mission is going fine until HAL detects a problem with one of the ship’s systems, forcing the crew to do a spacewalk to repair it. When it turns out HAL was in error, the crew decides they must disconnect it, but the computer learns of their plan and takes full control of the ship, killing one of the astronauts and turning off the life support to the hibernating scientists. HAL is eventually disconnected by the sole surviving astronaut, who leaves Discovery One in a space pod to explore a much larger mysterious black monolith found orbiting around Jupiter. The film now transitions to The Star Gate movement, which takes the astronaut on a wild ride across space, seeing bizarre cosmic phenomena and psychedelic planetary landscapes. He suddenly finds himself in a neoclassical bedroom (with a mysterious black monolith) in which he grows old, and is finally transformed into a fetus (The Star Child), gazing at the Earth.

The response

Today, 2001: A Space Odyssey is considered by many one of the greatest films of all time. But initial responses from audiences and critics after its opening were rather mixed. Audience complaints from the premieres about the slow pacing caused Kubrick to cut 17 minutes before the general release of the film. Even with that cut, the film still ran to 141 minutes, which made some viewers restless; some walked out. During the Los Angeles premiere, actor Rock Hudson stormed out, reportedly saying, “Will someone tell me what the hell this is about?”

Film critics were polarized. Some, such as from The New Yorker, called the film “monumentally unimaginative.” On the other hand, Roger Ebert gave it four stars, saying the film “succeeds magnificently on a cosmic scale.” Some negative critics reversed their reviews upon viewing the film again. Audiences warmed to the movie and eventually it attracted a loyal following and became the highest grossing film in North America in 1968. During the 1969 Academy Awards, it garnered four nominations (Best Director [Kubrick], Best Original Screenplay [Kubrick and Clarke], Best Art Direction, and Best Visual Effects) and won for its visual effects. In 1991, the Library of Congress deemed the film to be “culturally, historically, or esthetically significant” and selected it for preservation by the National Film Registry. In 2008, NASA joined the film’s 40th anniversary celebrations, sending down a special message from astronaut Garrett Reisman on the International Space Station (ISS) that was played during an anniversary screening of the movie.

The legacy

Although Kubrick did not envision any follow-ons to 2001, Clarke went on to write three book sequels (2010: Odyssey Two, 2061: Odyssey Three, and 3001: The Final Odyssey), the first of which was made into a motion picture in 1984, without Kubrick’s involvement. The sequel was a more traditional film and through its narrative clarified some but not all of the original film’s mysteries.

Many greats of the science fiction genre, such as George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, Ridley Scott and others, cite 2001 as a singular influence on their careers. The film opened a market for blockbuster science fiction films such as Star Wars, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Alien, Blade Runner, Contact and others.

David Bowie’s musical hit Space Oddity was released on July 11, 1969, just five days before Apollo 11 embarked on the first Moon landing mission and is often mistakenly believed to be associated with that historic flight. However, the song was actually first written in 1968, inspired by Bowie watching 2001 more than once. Enjoy the rare original 1969 video of the Bowie hit, which shows a certain relation to the film that inspired it

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D67kmFzSh_o.

Some of the technological advances imagined in 2001 have since come to pass. If you haven’t watched 2001 recently, you might be surprised by the prescience of Kubrick’s and Clarke’s vision. Although different in size and shape, the ISS is an Earth orbiting platform that is continuously occupied by a multinational crew conducting valuable research. And while space hotels don’t yet exist, there are some on the drawing boards for the not too distant future. Today’s computers may not have all of HAL’s abilities (probably a good thing), they do provide capabilities unheard of in 1968. And in a scene reminiscent of the astronaut jogging aboard Discovery One, astronauts aboard Skylab “ran” in weightlessness around the “exercise wheel” as seen here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S_p7LiyOUx0.

Historical perspective

The year 1968 was a turbulent one, and 2001 was released right in the middle of that chaos. The Vietnam War intensified, the US military stunned by the ferocity of the Tet Offensive earlier in the year. Fervent opposition to the war led to widespread and often violent demonstrations and police responses across the country. The Civil Rights movement was painfully gaining momentum through the 1960’s; Martin Luther King would be assassinated just two days after the world premiere of 2001. The Space Race was still very real. The Apollo fire that killed three American astronauts occurred only a little more than a year before the film’s release and the US was still trying to recover from that loss and still meet President John F. Kennedy’s goal of landing a man on the Moon before the end of the decade. No American had yet flown in an Apollo capsule, the giant Saturn 5 rocket had flown only once and without a crew (its second flight, also unmanned and which was only partially successful would take place two days after the world premiere). The high-risk Apollo 8 trip around the Moon hadn’t even been conceived yet. In April 1968, it was far from certain whether the Moon landing goal would be met, or whether the Soviets might beat us to it. The film’s premise of an extensive space infrastructure including a large orbiting space station staffed by international crewmembers, with regular trips to a lunar base by 2001, was visionary and highly optimistic at a time of great uncertainty.

Extra credit

Watch Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield perform a cover of David Bowie’s Space Oddity, inspired by 2001: A Space Odyssey, aboard the ISS in 2013: https://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=KaOC9danxNo#