On Feb. 19, 1986, the Soviet Union launched the first module of the Mir space station. Called the Mir base block or core module, this first element provided living accommodations, life support, command and control, and communications systems. During its 15-year lifetime, the Soviets added five research modules, including two partially outfitted with science equipment provided by the United States, to expand its capabilities and habitable volume. A docking module enabled the U.S. space shuttle to visit the complex to ferry American astronauts completing long-duration missions as part of the Shuttle-Mir Program. During its 13 years of human occupancy, Mir hosted 125 cosmonauts and astronauts from 12 countries, including the longest single spaceflight to date. Lessons learned aboard Mir facilitated implementation of the International Space Station (ISS).

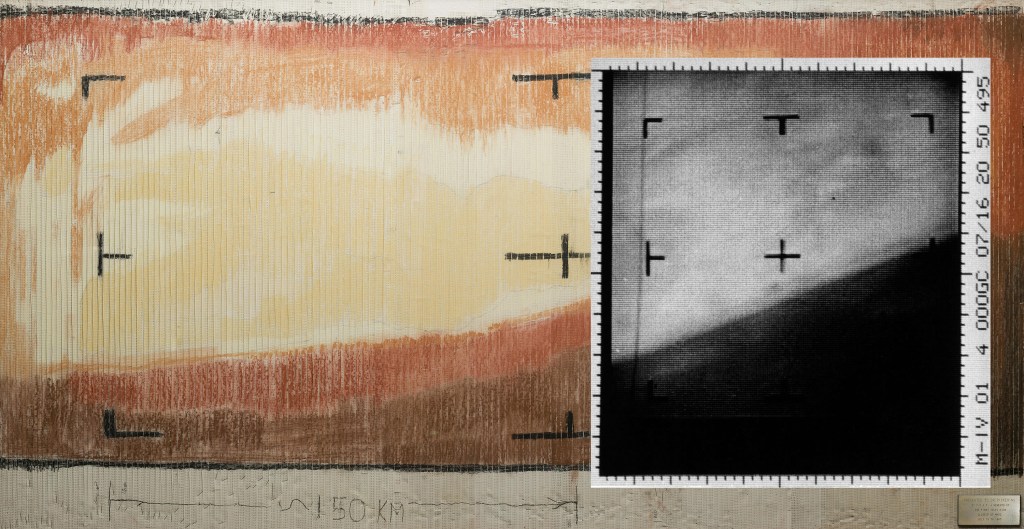

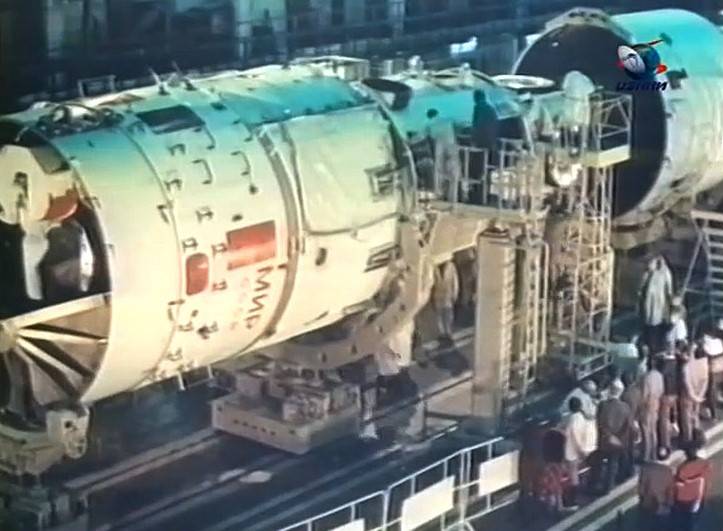

Left: Engineers at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan preparing to place the protective launch shroud over the Mir base block module. Right: Lift-off of the Mir base block at Baikonur.

The Soviet Union approved the Mir space station program in 1976, its elements based on hardware and technologies developed during the Salyut and Almaz space station programs of the early and mid-1970s. The most significant improvement involved the addition of a docking hub at the core module’s forward end that could accommodate four large research modules at its radial ports and a Soyuz crew spacecraft or a Progress cargo vehicle at its axial port in addition to the aft port that could accommodate a Soyuz or Progress. Together with other improvements in life support and command and control systems, the Soviets envisioned a long-term permanently occupied facility in low-Earth orbit staffed by rotating crews of cosmonauts. After several delays, the launch of the 45,000-pound Mir base block module atop a Proton rocket took place on Feb. 19, 1986, from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan. Nine minutes later, the module achieved orbit and unfurled its antennas and two solar arrays, and after a thorough checkout by ground personnel, it was ready to receive its first occupants.

Left: Leonid D. Kizim, left, and Vladimir A. Solovev, the first crew to occupy the Mir space station. Right: The Mir base block as seen by the space station’s first crew, with the multiple docking ports seen on the front of the module, at left.

The first crew to occupy Mir, Leonid D. Kizim and Vladimir A. Solovev, veterans of a seven-month mission aboard the earlier Salyut-7 space station in 1984, launched on March 13 aboard the Soyuz T15 spacecraft. Two days later, they docked with Mir, and as the new station’s first residents began to activate its systems. After spending 51 days aboard Mir, on May 5, they undocked in the Soyuz T15 spacecraft and travelled to Salyut-7, co-orbiting about 3,800 miles away, arriving there the next day. Kizim and Solovev stayed at the older station for 50 days, completing two spacewalks and finishing some experiments. They returned to Mir on June 26 with 880 pounds of equipment (including a guitar) from Salyut-7, completing the first and so far only station-to-station transfer. Kizim and Solovev ended their 125-day mission with a landing in Kazakhstan on July 16, leaving Mir temporarily unoccupied.

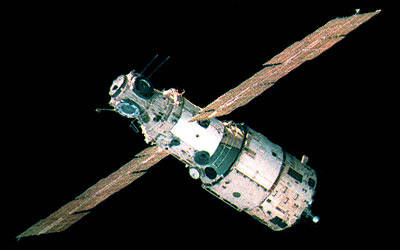

Left: Aleksandr I. Laveykin, left, and Yuri V. Romanenko aboard Mir with the guitar retrieved from Salyut-7. Middle: Mir with the newly arrived Kvant-1 module docked at its aft port. Right: Vladimir G. Titov, left, and Musa K. Manarov at the landing site after their one-year mission.

Mir’s next period of occupancy began in February 1987, with Yuri V. Romanenko and Aleksandr I. Laveykin taking up residence. They oversaw the first research module’s arrival, the Kvant-1 astrophysics facility docked to Mir’s aft port and installed a third solar array to increase the station’s power generation capability. Although Laveykin returned to Earth after six months due to a medical condition, Romanenko remained on board and set a new endurance record of 326 days. In December 1987, Vladimir G. Titov and Musa K. Manaraov replaced Romanenko and Aleksandr P. Aleksandrov, who had replaced Laveykin, and remained aboard Mir for a full year, a record that stood for six years. With the additional research modules running behind schedule, managers elected to operate Mir without a crew beginning in April 1989, after 811 days of continuous human occupation, the longest period up to that time.

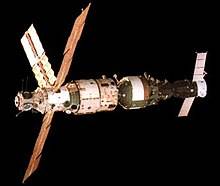

Left: Mir space station with the newly added Kvant-2 module at right docked to one of the radial ports. Right: The expanding Mir space station with the newly arrived Kristall module at lower left docked to the radial port opposite from Kvant-2.

The Expedition 5 crew resumed Mir’s human occupancy in September 1989, beginning 10 years of uninterrupted habitation that lasted until August 1999, a record not surpassed by crews aboard the ISS until October 2010. Teams of cosmonauts spent four to six months at a time maintaining and expanding the space station and conducting scientific research. The next two research modules, Kvant-2 and Kristall, arrived in November 1989 and May 1990, respectively, expanding the complex’s scientific capabilities and increasing its habitable volume. The Soviet Union and later the Russian Federation provided opportunities for individuals of other nations and space agencies to conduct scientific experiments during short-duration visits to Mir. Among them was British citizen Helen P. Sharman, the first woman to visit Mir during her eight-day mission in 1991.

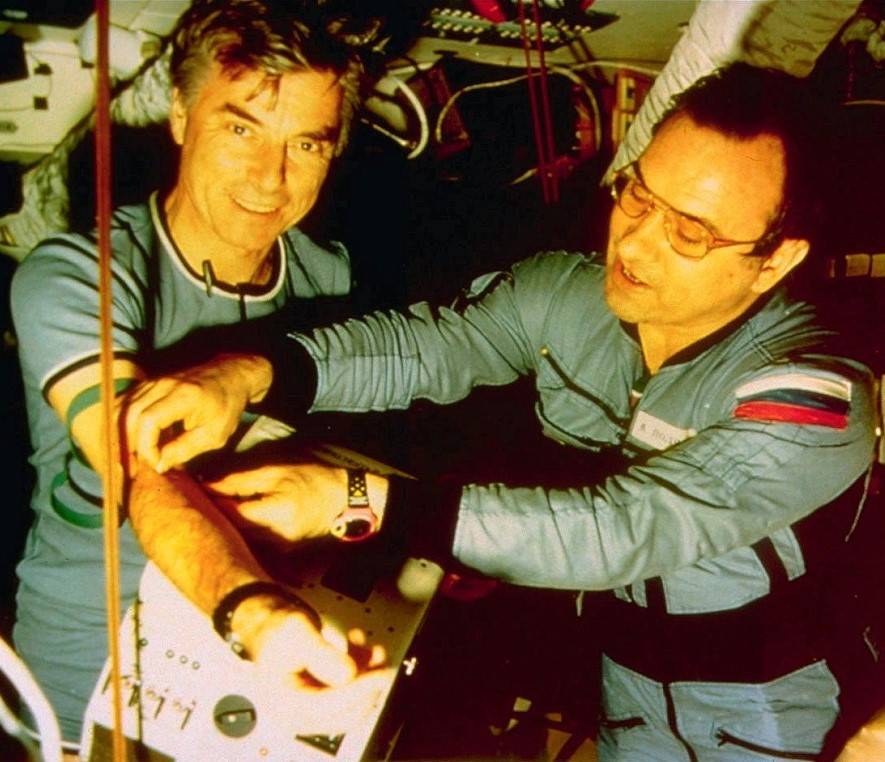

Left: Russian physician-cosmonaut Dr. Valeri V. Polyakov during his 438-day mission, drawing blood from European Space Agency astronaut Ulf Merbold. Middle: Polyakov, lower left, and American astronaut Dr. Norman E. Thagard, lower right, during their joint handover time aboard Mir in March 1995. Right: Polyakov toasting his successful landing after completing his 438-day mission aboard Mir.

In January 1994, physician-cosmonaut Dr. Valery V. Polyakov, already a veteran of an eight-month mission aboard Mir five years earlier, embarked on what became the longest single human spaceflight. Participating as a member of the Expedition 15, 16, and 17 crews, Polyakov lived and worked aboard Mir for 438 days, returning to Earth in March 1995. For six days at the end of his marathon mission, he worked alongside another physician, Dr. Norman E. Thagard, who arrived as the first American astronaut to complete a long-duration flight aboard the Russian space station as part of the Shuttle-Mir Program.

Left: The official patch of the Shuttle-Mir Program. Right: The seven American astronauts who flew long-duration missions aboard Mir – Norman E. Thagard, front row left, John E. Blaha, Jerry M. Linenger, and David A. Wolf; Andrew S.W. Thomas, back row left, Shannon M. Lucid, and C. Michael Foale.

The Shuttle-Mir Program, the first cooperative human space flight endeavor between the United States and Russia since the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project of the mid-1970s, grew out of bilateral government agreements signed in 1992. The collaboration provided a much needed opportunity for both sides to work together, particularly important once the international partnership brought Russia into the ISS Program in 1993. As initially envisioned, the Shuttle-Mir Program involved a short-duration flight of a Russian cosmonaut aboard the U.S. space shuttle, a long-duration flight of an American astronaut aboard Mir, and a space shuttle docking with Mir to return the astronaut to Earth. Central to this effort, conducting life sciences experiments while the astronaut was aboard Mir, provided NASA with its first long-duration human spaceflight experience since Skylab in the mid-1970s.

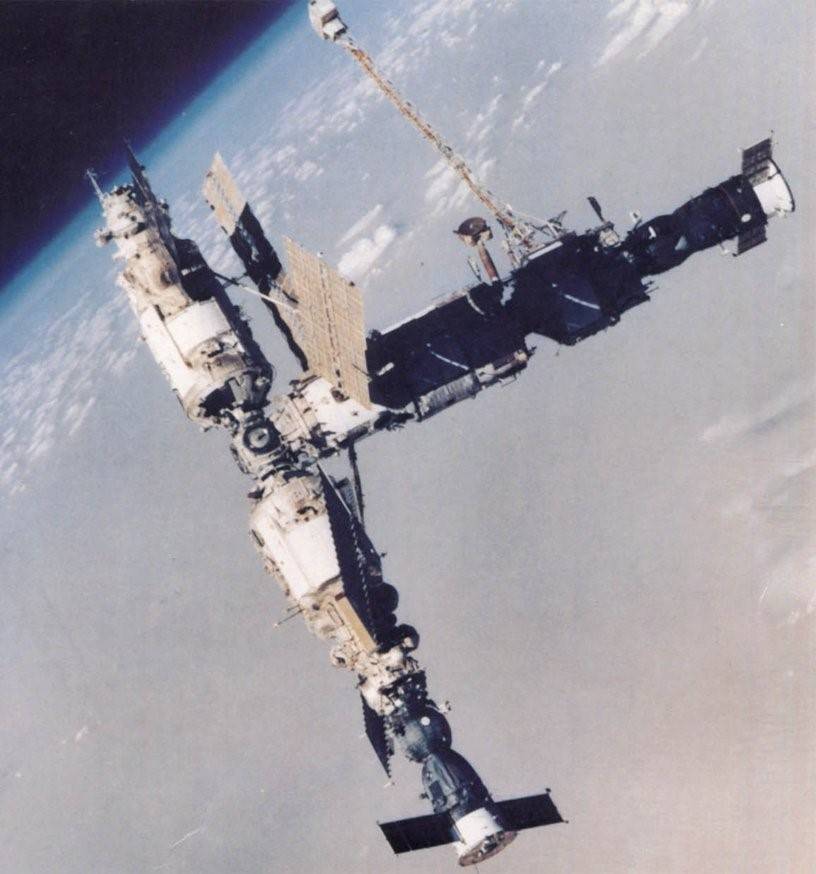

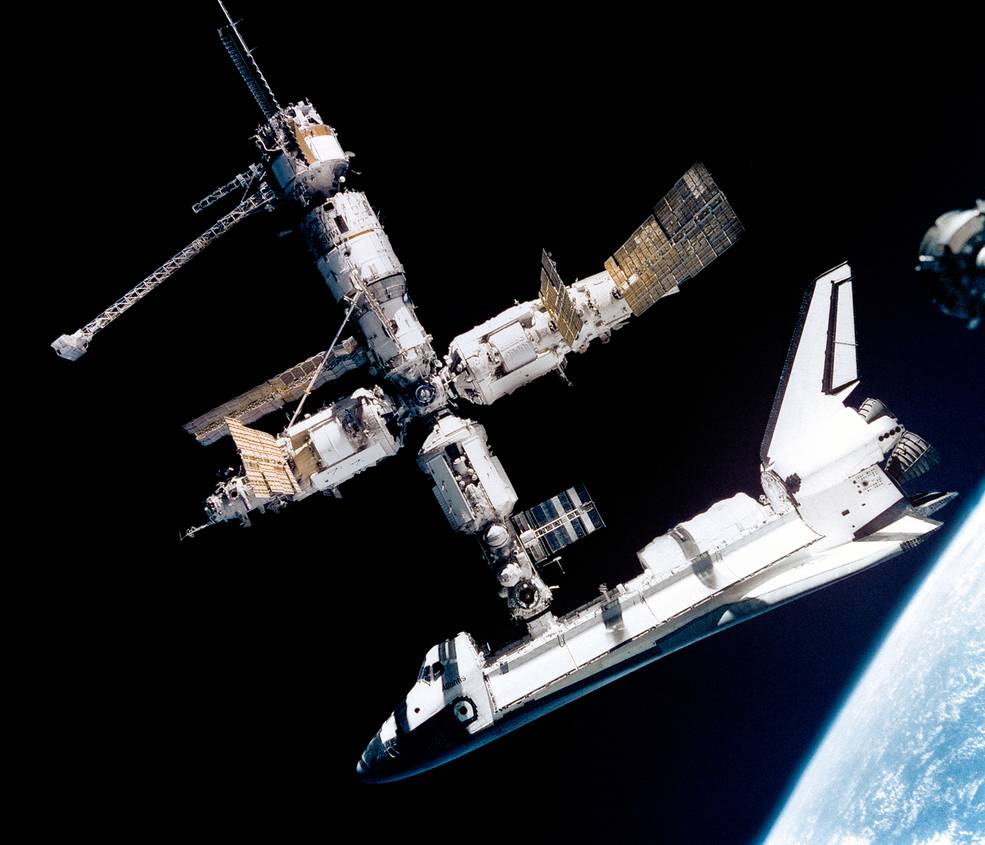

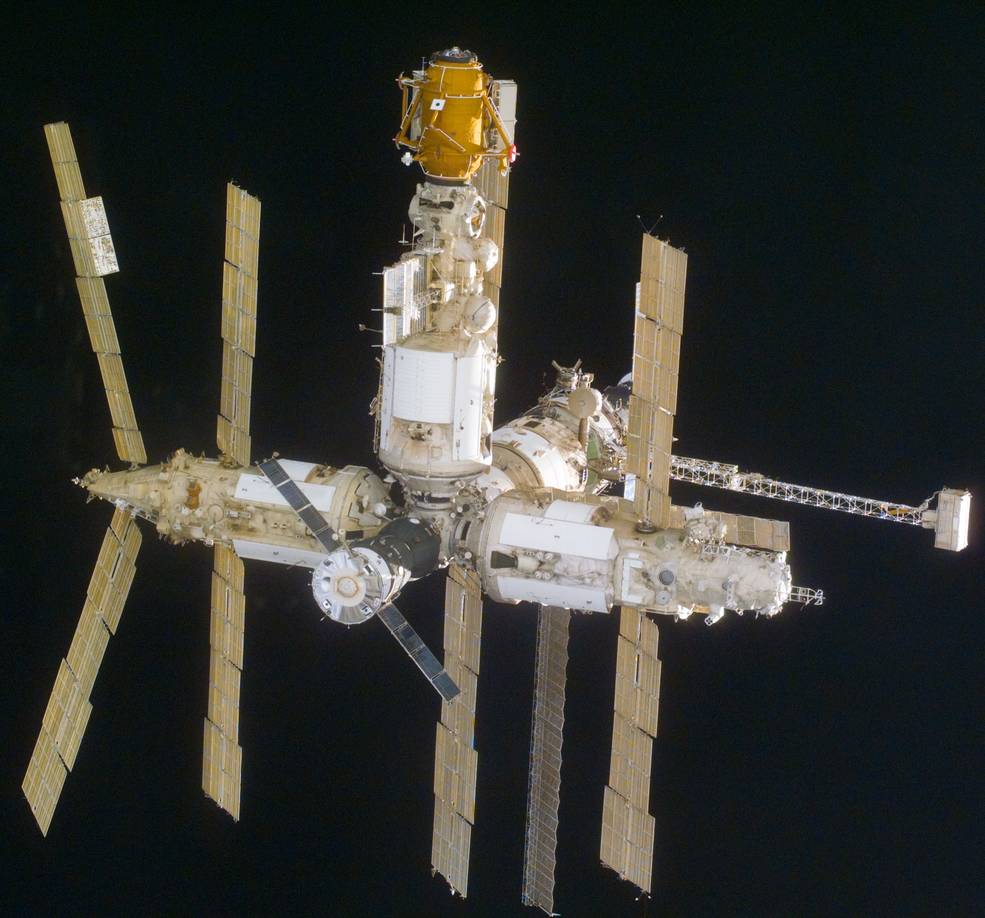

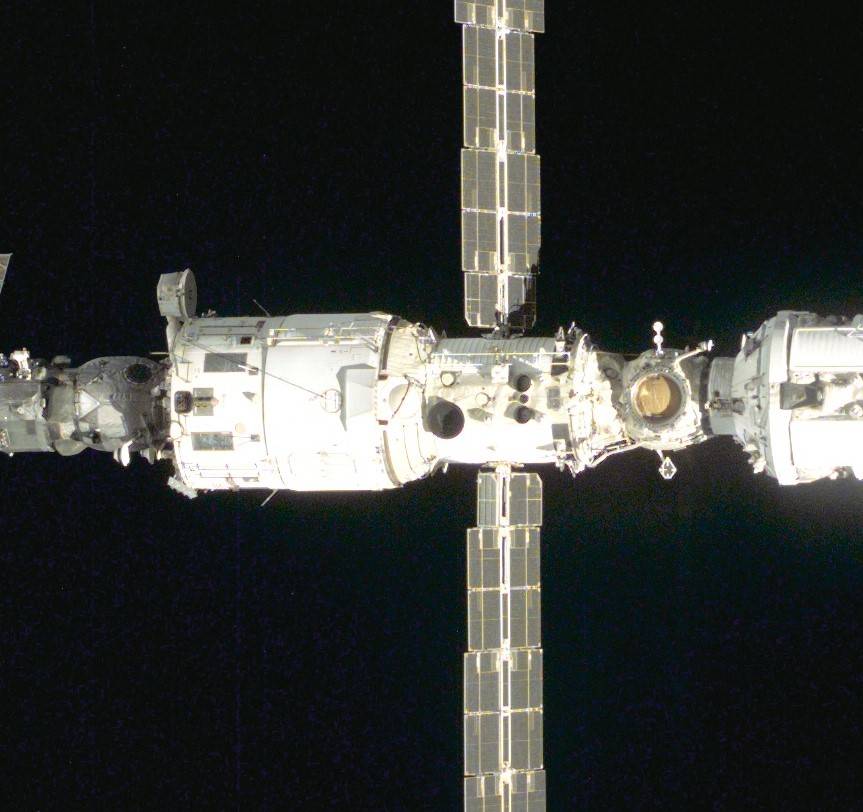

Left: Space shuttle Atlantis docked with space station Mir during the STS-71 mission, photographed by the Mir Expedition 19 crew aboard a Soyuz spacecraft. Middle: The Mir space station photographed during the STS-74 mission, showing the new Spektr module at left and the Docking Module at top. Right: Mir photographed during STS-91, showing the space station in its final configuration with the Priroda module added, at center of photograph.

To support the science investigations, NASA deployed research hardware to Mir, the first items launched aboard Progress resupply vehicles and the majority installed aboard Spektr, a science module that had been awaiting launch to expand the station’s capabilities. When the Shuttle-Mir Program later expanded to include six additional astronaut flights to Mir, NASA also outfitted the Priroda module with research hardware. With all its modules installed, the Mir complex weighed 285,900 pounds and contained 12,400 cubic feet of habitable volume, at the time the largest spacecraft ever assembled. To denote its strong link as a pathfinder for the ISS, the Shuttle-Mir Program was also known as the ISS Phase 1 Program.

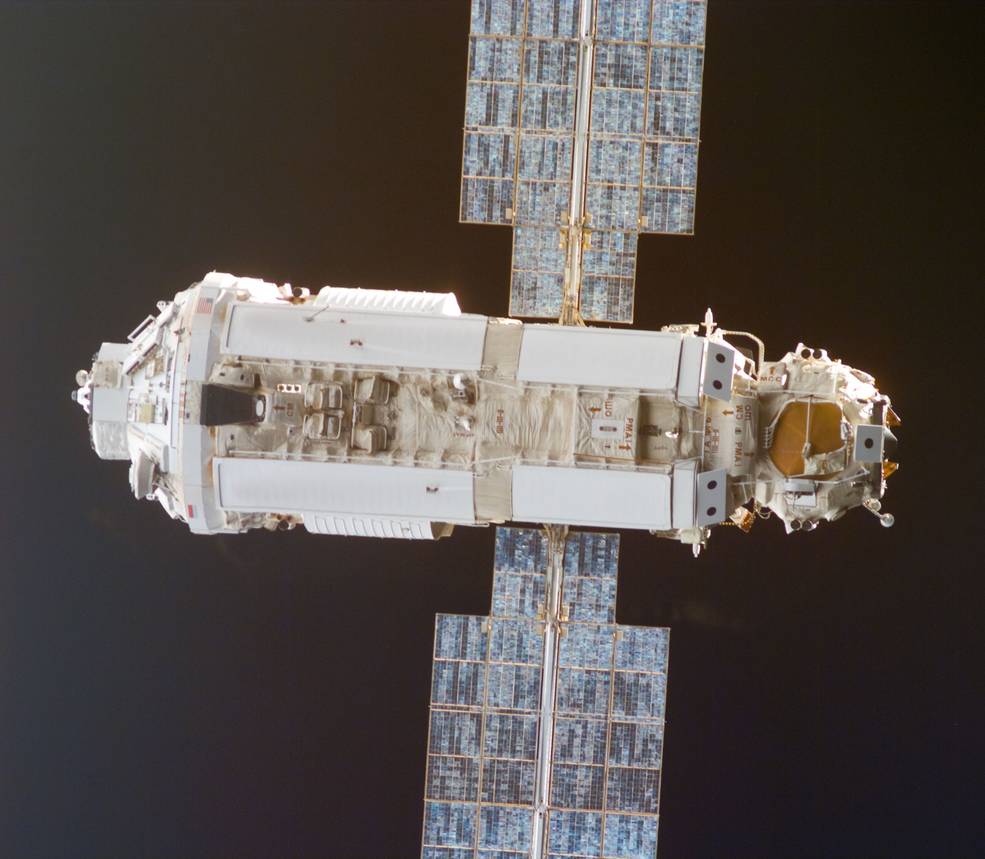

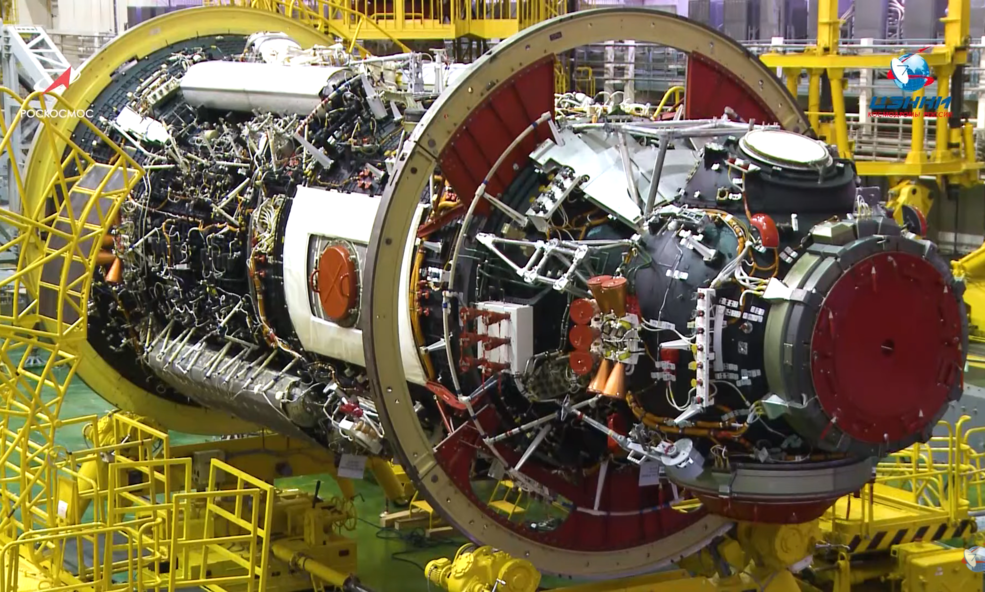

Left: The Zarya module of the International Space Station (ISS). Middle: The Zvezda service module of the ISS. Right: The Nauka research module undergoing preparation at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan.

Image credit: Roscosmos.

Although deorbited in 2001, Mir lent its heritage to the Russian segment of the ISS. The first element of the ISS to reach orbit, the Zarya module (also known by the technical term Functional Cargo Block module), shared its heritage with the Mir research modules that derived from transport vehicles planned for the Almaz program and tested in orbit in connection with the Salyut-6 and Salyut-7 space stations. The Zvezda service module served as the Mir base block’s flight backup, but incorporating newer technologies for its role on the ISS. The Nauka research module, built as a copy to the Zarya module, is currently undergoing preparation at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan for a planned launch in the near future as the newest addition to the ISS.

Left: The Mir program patch. Middle: Spacewalk record-holder Anatoli Y. Solovev. Right: The Chinese Tianhe space station core module is undergoing preflight testing.

During its 15-year orbital lifetime, Mir hosted 28 long-duration expeditions, including the three longest single spaceflights (438, 380, and 366 days) to date. Cosmonauts and astronauts from four countries completed 77 spacewalks, including the world record-holder Anatoli Y. Solovev who completed 16 spacewalks totaling more than 78 hours. Many cosmonauts and astronauts who visited Mir put that experience to use during the assembly and operation of the ISS. As noted above, elements of the Russian segment of the ISS trace their heritage to the Mir space station. As an additional note, the People’s Republic of China’s Tiangong and Tianhe space stations also derive their designs from Mir space station modules. In these derivatives, the Mir space station lives on.

John Uri

NASA Johnson Space Center