Hi Nathalie. We appreciate that you’re willing to take a few moments with us and create a work of art here! We normally start with your very young years, your family at that time, if you have siblings, what your parents did, the environment you grew up in, and so forth.

Hold on for a second. Give me two seconds, OK? I’m going to show you something.

(Returns with a book: “Voyage Aux Frontières De La Vie” by Nathalie A. Cabrol).

Do you read French? If you do, all the answers you want are in here! (laughs)

I don’t.

It will be released on September 23rd 2021, I finally caved in. I’ve been asked for a few years to write an autobiography and I finally did it. I mean the pandemic is long, so I kept busy at night writing last year.

So, you wrote a book! Congratulations!

Thank you.

I did look up your bio and one thing I looked for was about your early life, what it was that got you interested in what became planetary geology, which you wound up getting your Ph.D. in. But as a young person, tell us about your early life and what piqued your curiosity about the things that you’re studying and doing now?

You know, as far as my interest in planetary geology, I would say I don’t know where it started because I was born with it. My mom told me “You never talked about anything else”. But it wasn’t about planetary geology because it barely existed at the time. It was about astronomy. I was born close to the mid-‘60s and the first Mariners were barely starting to cruise in the solar system at that time. Most of what we knew about the solar system was still from ground-based telescopes. So for me, my first interest was in astronomy, looking up at the stars. I knew I wanted to be part of that because, very young, I already had many questions about the universe, and not only because I found it beautiful. My questions were already more along the lines of why? Why all of this exists and the meaning of it all. I wanted to learn everything about it. But planetary geology didn’t exist at the time, especially in France where I was born. It was starting to take shape here in the U.S. but in France, it was still a long way into the future and because of that, I was perceived mostly as a dreamer by everybody, except by my mom.

I was a straight-A student, including in math early on, but when the curriculum changed to modern math in high school, I became a little lost. I started having difficulties in physical sciences and math and it was a really hard time in my life. My teenage years were really, really, rough. It was a heartache that I carried with me. I wanted to be an astronomer but the only subjects I could not make the grades in were those I would have needed to fulfill my dream. I always say that the mistake I made at the time, which I think is the mistake that many youngsters make, is that I projected my future with my circumstances of that moment. Planetary geology didn’t exist and since I was not especially good in math and physics, I felt my world was collapsing. But what I didn’t know then was that I was a born naturalist. I discovered that in time and when I did, it set me on my course.

And, you have to give tomorrow a chance. Everything can happen, everything is possible if you do, and if whatever you want to do and want to achieve doesn’t exist yet, you can create it and make it happen. Once I understood that everything changed for me. When you are young, you expect (hope?) that maybe the adults around you will one day open a secret door for you to just walk in and live your life and be on your way. But that’s not how it works – most of the time. At least it didn’t work that way for me. And I was miserable as long as I felt that I was a victim of the others not understanding what I wanted to do or who I wanted to be, a victim of others not understanding what my dream was. The day I really understood that I was on my own path, everything changed. If the path didn’t exist, I was going to create it myself. That changed my perspective completely. Along the way, I had an unconditional supporter which was my mom. My dad had nothing against it but he felt I was going through a phase. Looking at it a few decades later, it’s been a long phase! (laughs). He saw something else in me: Since my early teens, I always loved writing and I still do today. I started to write short novels and articles. I was reading a lot too. I started translating articles from English to French in my early teens. My dad thought I would make a great writer, and because I was into sports, he saw me as a sportswriter or any type of journalist for that matter. He saw that in me, and he wasn’t completely wrong because I really enjoy writing.

I didn’t have siblings growing up. We should have been four. I would have been the big sister. It was hard on my mom and probably my life would have been very different if they had lived, but it was not meant to be. My parents were workaholics and I inherited that from them. But, as a result, I did not see them a lot and, without any siblings around, that contributed to my naturally introverted nature. On the other hand, it also probably contributed to give me that focus I have as a scientist. I was not really social and very introverted to start with. People laugh when I say that it is still true today. I had a difficult time making friends and wasn’t actually looking for it. I don’t know how to explain that but I was a little bit on the awkward side. Maybe a little high Asperger can explain some of it. It is not high enough to be problematic but high enough to explain why I am good at being interested in a lot of things that other people are not interested in and loving tables of numbers and data analysis. Who knows? From very early on, I loved writing codes, not computer codes, but codes like in ciphers. I also had this habit of always reading right to left or down up first and finding hidden patterns. With time, I called it my mirror brain. Don’t ask why, and I’m still very good at that today, and also very good at connecting things that other people have absolutely no interest in connecting. But I think that was an incredible training for what I’m doing today because Astrobiology is connecting dots in so many unique ways. In more than one way, I was unknowingly grooming myself for what was to come.

What did they do, your dad and your mom?

My mom was an x-ray technician and my dad managed computer accounts for an accounting company, today’s IT if you prefer. In those days computers that would fit on your watch today were as big as a room. My dad took me to work one day to show one to me. I might have been 6 or 7 years old. This thing was huge! So, when you think of it, my dad was in computing and my mom worked with x-ray imaging. I think it’s not too far-fetched for me to be analyzing and processing planetary images using computers, at least for part of my research. I spent a lot of time until I started at the university doing my homework in my mom’s x-ray lab, and whenever she had time, she would show me the x-rays and teach me how to interpret them. She trained my eyes.

So, as you matriculated, at some point you were choosing majors and courses, disciplines to pursue, that landed you into this geology and eventually planetary geology, so can you kind of take us down how that interest developed? Was it just looking at stars and wondering about them?

Oh no. I was also very much interested in rocks and if my grandma was still alive, she would say what she kept repeating to me: that I either had my nose in the dirt or looking up at the sky, but I was never looking in front of me when I was walking! (laughs) I was interested in crystals and minerals. But, since I had a hard time with math and physics going through high school, I got a baccalaureate in literature and philosophy first. I was also one year younger than the average in my class, so my mom asked the high school Principal if I could do what is now called a double major. Because I was a year ahead and I had already some of the credits, she asked if it would be possible for me to enlist again in the last year of high school but this time in a scientific section? France’s system is a little different and to the credit of my Principal, since a double major had never been done at our high school, and it was still very rare in France, but she agreed and she let me do another year. Today, I continue to joke that I actually graduated in literature baccalaureate thanks to math and actually flunked my baccalaureate in science because of philosophy (that’s true)!

At that point, I said, alright: I’m 17, it’s time to make a decision. I just cannot continue to go back and forth. This is when I decided to go for what we call in France a prep school, but it has a different meaning in the U.S. If you want to compare it to something, the closest would be West Point for the army. Basically, it’s a school, or a group of schools, some of them are in philosophy others are in sciences, that prepares the elite in France, you know top-ranking politicians, engineers, professors for prestigious schools. I didn’t want to be a professor in one of these very fancy schools, I didn’t want to be a politician, but I knew what this school would bring me, and that was a work method, that is, if of course, I could survive it because it was really like a boot camp. First, my application needed to be accepted but I was a good student and I guess that my request of going through two baccalaureates (willingly! – laughs) gave me some credits in the eyes of the selection committee.

So, the goal was that after a year of that regimen – and if I could make it through the entire year – you are given credits and can enlist right away in the second year of university. No time wasted. That was probably the best decision but, OMG, that was brutal, exactly as advertised. We started 36 students at the beginning of the year and three weeks later we were 17 left. Besides the fact that the professors we had were absolutely fantastic, I finally understood then why I had been learning Latin grammar for five years. We read the war of the Gauls in the text among others. One of my favorite memories is of our professor of French. The first day we met her, we saw this petite, energetic young French woman who, after only five minutes with us, looked at us and said: “Take a sheet of paper and a pen, please. We are going to do a dictation”. We looked at each other and said, “What the heck?” So, we grabbed a piece of paper. We all had a smirk. We had just graduated from high school, so we were know-it-alls, obviously. She started dictating and within two seconds we understood that we were not playing in the same league! A week later when she gave us our copies back, we also learned that in prep school grades could be negative! (laughs).

But in answer to your question, Fred, it was during that year that I met a professor of physical geography. He was as fascinating and as passionate as all the other professors we had, and all of a sudden it made me realize that there was an entirely new world that I was interested in: physical geography. We were talking about physical processes, not the boring stuff that was taught in high school, like world market economy and blah, blah, blah. He was talking about climate, hydrology, geology, and from day one I was just absolutely hanging on to every single word he said. I became the best student in his class. We had a great interaction and then every three weeks or so, he would ask me to teach the class for the rest of the students because one of the goals of this prep school was to prepare the students to be professors in elite schools. So, in his mind, he was preparing me to do that, to go for the full cycle of two years of prep school, and the exit exam. I told him that this is not what I wanted to do. I was here to acquire a work method. He kept training me in hydrology, climatology, and the formation and evolution of landscapes. I worked hard and, by the end of the year, I obtained my equivalence certificate and then I enlisted directly in the second year at Nanterre University, where I chose physical geography and environment in the Earth sciences department. During that year, I finished the general teachings and then started the third year, going into physical geography, environment (particularly environmental hazards), remote sensing, climatology, hydrology. This is where things really started to shape up for me.

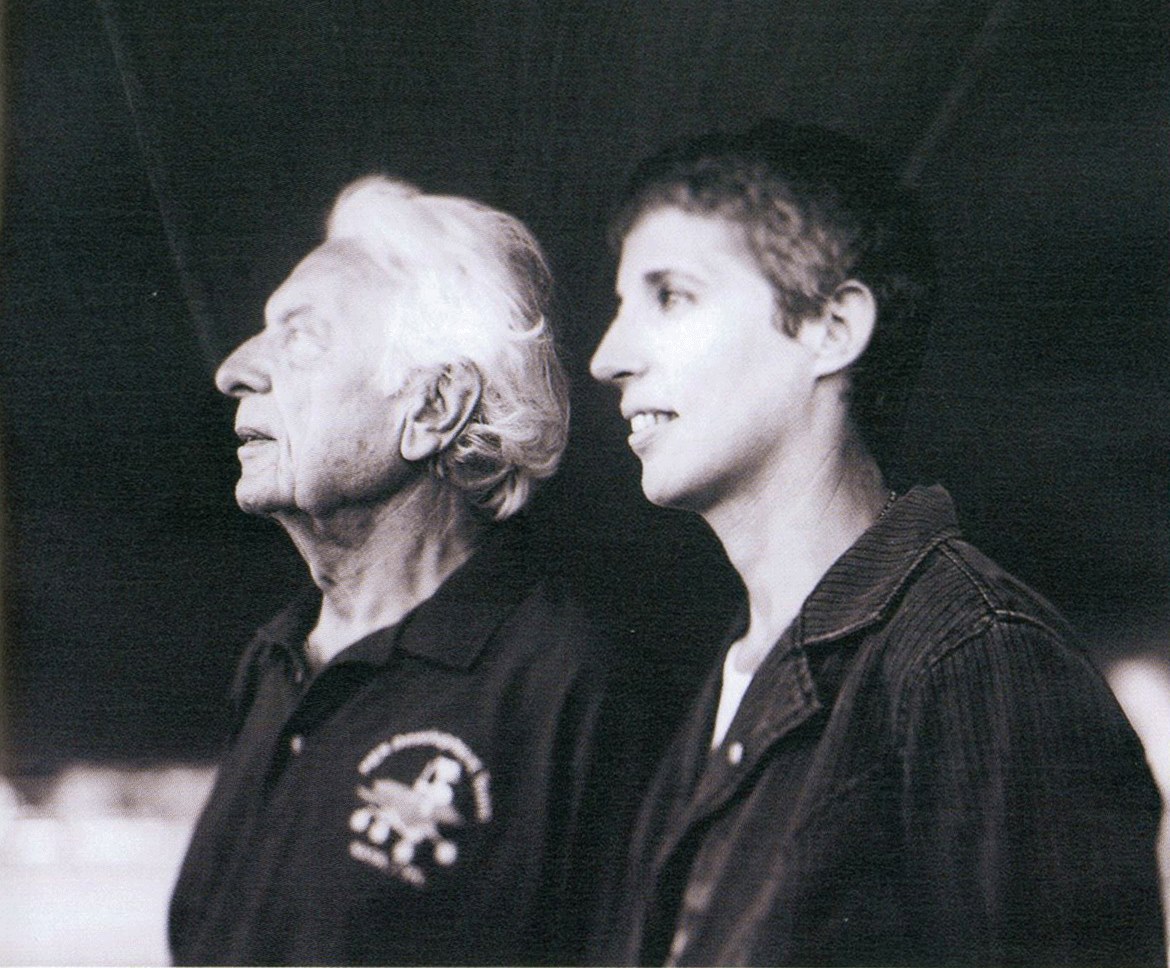

Although I was still carrying with me magazines about astronomy and planetary exploration, and everybody knew this was my passion because of course, I could not stop talking about it, I finally had started to accept that maybe I could do that on the side, as an amateur astronomer. In the meantime, I would be working on environmental research, which really interested me. Our lab worked directly with the French Ministry of the Environment and performed assessment studies for environmental hazards such as avalanches and floods. We were hands-on, and in the field, which I liked. I had fantastic professors at Nanterre University, and I felt that I had found my groove. Today, I would probably still be there if it wasn’t for one thing. I was talking so much about astronomy that even my advisor-to-be for my master’s thesis knew about it. We were at the end of May of 1985, and I was one week away from signing with him for my master’s thesis in environmental sciences. I was busy preparing my project outline when I met him in the hallway and he said: “Nathalie, you know I have a colleague, his name is André Cailleux and he’s doing something new. I don’t know what it is exactly, I think he called it planetary geology. I know you are interested in astronomy so, if you want, I can arrange for the two of you to meet and talk. I responded distractedly, something along the lines of: “Sure”. I was really somewhere else in my head. I was preparing my project for my master’s thesis, but I said “OK, sure, fine, thanks”. The next day, he told me that André has agreed to meet me at the Observatory of Paris, Meudon, where he was located now. André Cailleux was already emeritus from the Sorbonne University but spent some time at Meudon to work each week.

On that Thursday I went to spend the day at Meudon, and I met André Cailleux and Audouin Dollfus, the astronomer and director of the lab. We chatted. André told me about the research at the lab. They worked on Viking images. I knew, of course, what the Viking mission was but had never seen anything related to it. He showed me a number of mosaics and images and told me the lab was working on everything related to water on Mars, whether it’s the permafrost or ancient water. He asked me then if that would be of interest to me. He showed me more mosaic maps of Mars and one of them caught my attention. It showed a big channel ending in an impact crater. The names on the atlas said Ma’am Vallis and Gusev crater. This system really caught my eye right away, and then for some reason, I still don’t understand today, André implicitly thought that this was what I wanted to do. I had never talked to him before. I had never met him although he was a God in geology worldwide. But he took it as me wanting to work on those images.

This is how I came to Meudon at the end of May 1985, for a chance of a meeting of a lifetime, without really thinking about it. And I left nine years later with a master’s thesis and a Ph.D. in planetary geology. This is how destiny caught up with me at a time when I thought I was heading 180 degrees away from my dream. And this is really my message for the youngsters: Belief in yourself; follow your path, work, and improve your skillset always. What you want probably doesn’t exist exactly as you imagine it and the path might not be straightforward. But keep at it, and never give up. You never know when it’s going to catch up with you but as long as you keep walking and working, you create opportunities. Me, I could have said “No” to the meeting, and who knows what would have happened then. I was happy at Nanterre university. But more importantly, I know today what would not have happened. The meeting with André Cailleux changed my life and set me on my course. My universe got scrambled again and this new path led me to even more incredible encounters, and to NASA Ames.

I was just going to ask about that. Your story is quite fascinating and your life has been really a great story but one of the things we do probe into is at what point, well, I’ve read in your bio that there was an encounter with Chris McKay, so tell us a little bit about that and what got you to NASA Ames.

Well, there is the front story but there was also a lot going on in the background. I was at Meudon, and the master’s thesis was just a dream come true. Everything I’ve dreamed of at that point, as a little girl, even the drawings I made when I was five years old! I always drew exactly the same landscape, a dark sky with Saturn in the background and two moons and a hill with domes on top of it. Then, that day when I met André Cailleux for the first time and visited the lab, I also met Audouin Dollfus, the director of the lab. Dollfus was a renowned astronomer. He was an expert in polarimetry, and among other things, he discovered Janus, the little moon of Saturn. That day, in his office, the first thing I saw was a photo of Saturn with the moon he discovered there and its co-orbital companion, Epimetheus. The observatory is also located on a hill and the lab was surrounded by domes covering telescopes. That was my first day at Meudon…

André Cailleux became my de facto advisor and mentor. It was such a privilege to have him one-on-one. But then the whole master’s thesis was just an incredible blessing. I was on cloud nine. I was working during the day and observing at night at the Grande lunette of Meudon. I loved using the other telescopes as well. And then in December, six months after my defense, André passed away and things changed. Planetary geology was a nascent field in 1986, and there was a bit of a war of succession at that time. I was being pressured to change advisors and I did not want to. I was happy with mine, and I had two (!) because we did not have any planetary geologists per se in France yet. One was Audouin Dollfus, the astronomer at the Observatory of Meudon. The other was Alain Godard, a geomorphologist at La Sorbonne University. That’s also why I changed university then going from Nanterre to La Sorbonne. Because I stuck with my principles (and my advisors), I faced more challenges than I cared for, but it ultimately worked out. I defended my Ph.D. thesis in December 1991. By 1992 I was looking for a job at Meudon. By then, the local astronomers knew my work after hearing me in conferences and seminars. They understood better what planetary geology was too. I thought that I had a really good shot at getting a position there. The issue was that new positions were rare and you had to have a very powerful lab director to support your candidature. Dollfus was a great and respected scientist, but he was about to retire. He supported me and helped me as much as he could, but that was an uphill battle.

Then in ’92, while I was on a postdoc at Meudon, I went to Val Cenis for a conference. This is where I met Chris McKay for the first time. We talked about my work on the evolution of water on Mars. At that time, I was starting to look at the possible formation of lakes on Mars in impact craters. I also continued my work with Gusev crater and Ma’adim Vallis. I met Chris, but it didn’t go much farther than that then. But Chris used to come to the observatory at Meudon twice a year and I could see him jog on the road next to our lab every day. One day, In ’93, I saw him at the cafeteria and he seemed bothered by something. That prompted me to talk to him and he told me that he was working on a concept for an astrobiology mission to Mars. He had the technology but he did not have a study for a landing site to go with it that would make it a good mission to search for life on Mars. I invited him to stop at our lab the same afternoon and told him there was something I wanted him to see. He came a few hours later and I showed him Gusev and Ma’adim Vallis. By then, I already had developed maps with Edmond, my husband, and we were fairly advanced. We showed him what we knew about it. During the same period, I postulated for another postdoc, this time from the French Ministry of Research. I ended up being selected but the government had changed, and the budget was frozen. The money was not available yet.

Chris left, but before he did, he asked me if I wanted to come to visit NASA Ames for a week in the fall and talk about my work. This is how I came to NASA Ames for the first time in early November 1993. I didn’t know this was an interview. I presented my work to the Space Science division scientists, then, I went back home. I was really grateful for the experience, but I didn’t hear anything further and I had no position in France. My new postdoc was still not starting because the money was frozen but then, everything changed. Chris showed up again in the spring of 1994 and by that time the money had finally been released by the French Ministry of Research. My Ph.D. advisor Audouin Dollfus was retiring and the lab was closing in October. I had nowhere to go and Chris asked me if I wanted to come and complete this new postdoc at NASA Ames with him as my technical monitor. I’ll bet you know the answer to that question! (laughs). I did not hesitate. I closed the lab at Meudon and boarded a plane with Edmond by my side. We only had one piece of luggage. We were only leaving for 9 months after all… And, this is how we ended up at the San Francisco airport on Halloween night in 1994. My first day of Ames was November 7. That was over 27 years ago now.

Wonderful! Your path is a little zigzag but fairly direct in terms of what you’re doing but have you ever thought that if you weren’t doing what you’re doing now, what your dream job would be?

This is my dream job! (laughs) I never wanted to do anything else. I could not really realize, when I was a kid, what that dream was exactly about. My dream was about the universe and then only astronomers were studying stars. But I could not be an astronomer. On the other hand, I was a born naturalist, and astrobiology and planetary geology allowed me to fulfill that dream.

We usually ask what you like best and least about your job but I don’t even think I have to ask you because reading your bio, you’ve been fortunate enough that a lot of your work has been done at locations around the world, in the Andes, the Altiplano, and the Atacama, in volcanic lakes, and so forth, and you’re a diver. So you’ve really been out there and that’s got to be more enjoyable than sitting in a lab or putting up with bureaucracy, things like that.

I think the secret is that I never wake up in the morning saying, “I’m going to work”. Never, ever! If there is a little downside to it, of course, it is that I’m a contractor, and I have to compete for everything all the time. On the other hand, I would say that this keeps me on my toes and forces me to always strive to be the best I can be. I was, as you say, fortunate enough to be able to combine two great passions, diving, and mountaineering. Being able to do that while deploying large multidisciplinary teams in extreme environments absolutely changed my life in many and profound ways because, as I mentioned earlier, I was introverted and not very social earlier on, and being a team leader in the middle of some of the most extreme places on Earth, well, you cannot be asocial or introverted and, even if you still are, you have to forget about it! (laughs)

Well, it is certainly a very full spectrum of work that you’ve been involved in but what do you do for fun?

My work! (laughs) What do I do for fun?

Yeah, like hobbies, interests for places you like to go or things you like to do when you’re not at work.

Now that I’m wearing two hats, as a scientist and as the Director of the Carl Sagan Center…

You don’t have time for fun?

You know, as I said, part of it is that what I’m doing is fun to me. I like to trek, climb high mountains, dive, so pretty much what I do in my scientific explorations. Writing my book also reawakened an old (and good) “demon” in me. I always loved writing. Because of personal circumstances, Edmond can’t always do the things we used to do together because he’s elderly now. We are very close and I don’t feel necessarily that I want to do things without him. There is also the pandemic right now and it’s not easy to go places anyway. So, in my writings, I go places in my mind and for now, I am fine with that.

Right. That’s a good one. We ask about the things you do like hobbies, other talents, obviously, you’re a writer, but maybe musical instruments?

Music is part of my life. Music and water. Actually, I have a joke about this. I say that I absolutely need two things in my life – besides my husband obviously: one is water and the other is music. And when you look at very serious studies on the subject, that’s pretty much what any vegetable needs to grow (laughs). Except that, unlike vegetables, I cannot keep my feet in one place! I never was able to and never will be! (laughs). But music is central to my life, absolutely. My parents tried to send me to a music school. They were not rich and they sacrificed so much to give me the most they could. So they tried that too. I was very good at reading music and conducting music, but I don’t know if it’s because of the way my brain is wired, but music stayed stuck between my brain to my hands, and I was never able to play any instrument decently. That’s really something I regret deeply because I would love to bring an instrument on top of one of these towering volcanoes I climb and play there. That would be so special. On the other hand, I’d say that life made me a conductor of a different kind. I really love writing projects, writing proposals. People think I’m nuts because I really like this type of writing but this is truly the creative part of our work, right? I put music on while I am writing and when I read the text again, oftentimes I can feel the rhythm in it. So yes, music is very, very important to me. It can change my mood on a dime.

Yes, it has that power for sure. So, have you ever thought about what accomplishment you’re most proud of that’s not related to your science work?

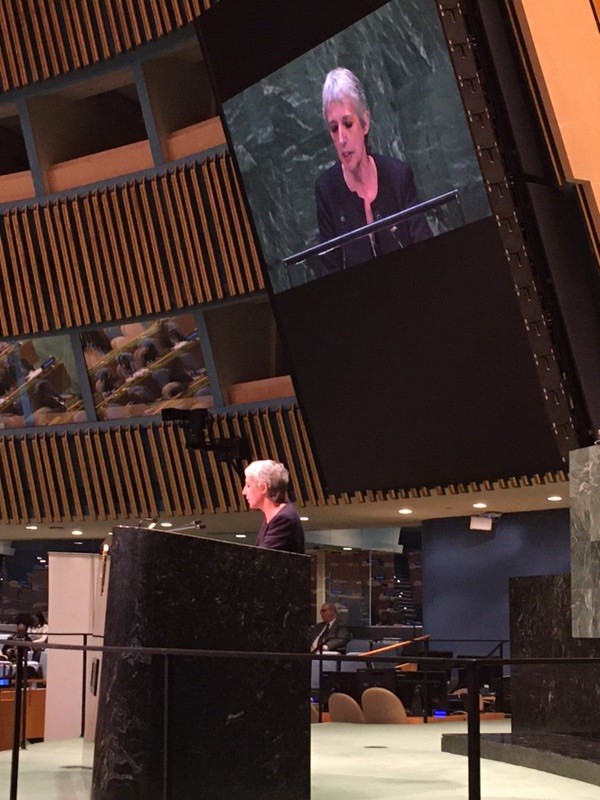

I don’t know if it’s an accomplishment but I love this country very, very, much, Fred, and for me, it was deeply meaningful to become part of it and become a U.S. citizen. I was born in France, and I love the country I was born in, but it was the U.S. that gave me the chance to make my dream a reality. People accepted me without knowing who I was, where I was coming from, or anything but just that I could contribute something. So, I’d like to give back in every way I can. One way is to help restore and preserve the forests and the National Parks, especially considering what’s going on with the environment right now. I enjoy them so much and it is a legacy to pass on to future generations. I believe this is important and probably it will take a greater place in my life in the future as well. I want to make sure that I do my part. I know it’s a small contribution in the great scheme of things, but right now every single tree planted will be part of a healthy planet that we are trying to reclaim, also a way to try to understand how to coevolve with it in a sustainable way. Then, on the work side, as the Director of the Carl Sagan Center (CSC), I just finished writing the Strategic Vision (for research) of the SETI Institute and in it, I made sure that the preservation of our environment is absolutely central. Our planet is front and center in it, and I open the CSC to more environmental sciences. I want us to take the science and technologies we develop for space and planetary exploration and use them for the benefit of our planet right here and right now. As for my research, I will continue to explore this planet and others to understand how life and its planetary environment coevolve.

That’s very noble.

It’s not noble, it’s an emergency now and we need to work on making our presence sustainable because, and excuse me for being blunt now, but we are completely F’d up if we don’t. Our planet is changing in front of our eyes every single year. People do not realize it, but it’s not a matter of generations. This is our generation, or never.

What are your favorite quotes?

One of my true favorites is actually not a quote but part of a dialogue at the end of the movie Cast Away. It’s something I could relate to a number of times in my life and it’s about resilience:

“I know what I have to do now, I’ve got to keep breathing because tomorrow the sun will rise, and who knows what the tide could bring?” (Chuck Noland, Cast Away).

Other quotes: “Success is not final; failure is not fatal; It is the courage to continue that counts.” Winston S. Churchill.

“We began as wanderers, and we are wanderers still. We have lingered long enough on the shores of the cosmic ocean. We are ready at last to set sail for the stars.” Carl Sagan.

Nathalie, this has been wonderful. You have had a very amazing path, very inspiring.

That’s why I finally accepted to write a book. There are a number of things that are very painful in my past that it was hard to revisit, and I’m also somebody who’d rather look forward than back. That stopped me from writing for a number of years. However, I finally accepted because I felt there were some good lessons learned and also a very positive message to be shared, which is ultimately that of a fulfilled passion and a dream come true. Of course, my experiences, and everybody else’s, are personal and unique, but there are common threads. I can understand how this generation in particular may feel lost and uncertain about its future. In part, it’s because (I think) many are still waiting for others to show them the way and tell them what they should do or how they should do it. Our planet is in dire need of strong leaders now and pathfinders. We have to redefine our own coevolution with our environment. Our current ways are outdated. We must write a brand new and wiser chapter, and there is no predigested script for that. It is both frightening and exhilarating. It is the ultimate exploration, that of our own survival.

Well, I hope (the book) makes you rich, too! (laughs) Thank you so much for taking this time to chat with us, we appreciate it. We’ll put this on paper and get it back to you to adjust however you’d like and add anything you wish you had said but didn’t, or vice versa. We thank you so much. It’s been a pleasure.

Yes, it has been a pleasure.

Interview conducted by Fred and Sara on 8/3/21