We like to start with your childhood, where you are from and was there anything about your young years that pointed you to where you are today?

Sputnik and I are pretty close in age, let’s just say that. My father was a physics major, and so definitely was interested in science and encouraged me in science. My maternal grandfather, a pediatrician, really wanted me to become a doctor, especially as I was the eldest, and none of his other grandchildren had any interest in science.

Can we start with where you were born and grew up?

You can’t tell? New Yawk! (laughs) When I hear myself, I always feel like I sound so heavily New York. I was told that I was born in the same hospital as Caroline Kennedy, a couple of months off. At least half of that is true.

So, New York, New York!

Yes, New York, New York. I lived in Riverdale (of the comic strip “Archie” fame) in the Bronx until I was eight, but Dan Goldin informed me that it doesn’t count as the Bronx because it’s too far north. We moved to Connecticut when I was eight, where I went to a public school in Greenwich. It’s the same town that George H.W. Bush was from, as well as Dorothy Hamill who is my age. We would have been in high school together, but by that time she had a private tutor. You probably remember she won the Olympics in figure skating. Anyway, I never met her.

How did I become interested in science? I remember we had a section in third-grade science when we spent three days looking through a microscope, and that was the critical point in my life. The first day we looked at a human hair. The second day, onion skin cells, and the third day I saw an amoeba, and that was it (snaps fingers) – I was hooked! So I’ve wanted to be a protozoologist literally since I was eight years old. Many people at Ames don’t realize that I was president of the Society of Protozoologists a few years back. I’ve worked in a lot of phycology as well: they nominated me for president of the Phycological Society a few years ago and I’ve given a few plenaries for the Society, including one coming up in June 2021. Phycology is the study of algae. Algology is the Latin, and phycology is the Greek. Anyway, I really wanted to study what my dad called “little wiggly things”, and so I started doing the sort of things kids like me do, such as bugging my parents for a microscope, taking smelly jars with water, and raising my own protozoa and algae (protists), hopping in ponds, sinking knee-deep in the mud, and all those things. I’m blessed to have a job that still lets me do that kind of fieldwork, whether in the SF Bay or the Bolivian Andes, Kenya, or Yellowstone.

When I was an undergraduate at Yale, it was at the end of the period when they were a – or even the – dominant university, certainly in the U.S., in phylogeny [the evolutionary development and history of a species.] Yale had on its faculty the founder of modern ecology (G. Evelyn Hutchinson), the world’s expert in birds (Sibley), and dinosaurs, John Ostrom who figured out that dinosaurs were warm-blooded. I had semester after semester of invertebrates from the world’s foremost sponge phylogenist, Willard Hartman. And so I ended up with a very strong organismal background. Most students don’t get that today, which I think is a huge, huge, mistake. So I probably could “out-phylogeny” eukaryotes with anyone else at Ames – but I wouldn’t dare try to compete with Rocco Mancinelli – the walking Bergey’s Manual – on prokaryotes! There is this amazing diversity of life out there and you should know about it, especially if you are going to look for life elsewhere. Unfortunately in biology today there is too much focus on the molecular and not enough appreciation for the organisms.

In my junior year, Professor John Preer Jr. from Indiana University, a very well-known ciliate geneticist working primarily with paramecium, was doing a sabbatical at Yale. I went to his departmental seminar and followed up with an appointment. He told me I was the only undergraduate who had come to see him and asked if I had thought about going to Indiana for a Ph.D.? He pointed out that the great Tracy Sonneborn, the god of protozoan genetics, was there. Tracy Sonneborn may have been the cleverest scientist I’ve ever met and was often on the shortlist for the Nobel prize. He really opened up this whole field of paramecium genetics in particular, but ciliate genetics in general, a field which ended up yielding several Nobel prizes, including ones for Elizabeth Blackburn and Tom Cech. Dr. Sonneborn was a pioneer in understanding extra-chromosomal inheritance, and that the father’s age had an effect on birth outcomes among other things; he was amazing. My advisor had been one of his students in the 1940s, and another one or two of his students were also on the faculty. The three or four of them had been together more or less for forty years, so I was the baby of the lab. And when I say baby, I had an office with a retired professor from Wellesley who was up in her early 90’s, I mean I was the baby! By a lot! The worst part was the day after I arrived Sonneborn had a heart attack, so I ended up calling the chairman of the department of Maryland, which was my second choice because he was the great ciliate phylogenist, John Corliss, and I said, “Can I come at least for a semester?” I ended up double enrolling for a semester, going to the University of Maryland where I learned protistan phylogeny and ultrastructure but decided to return to Indiana, for the strength of the program, the same program that Jim Watson, co-discoverer of the DNA double helix, had also graduated from. Interestingly, Dr. Preer had started his Ph.D. in 1939 with Alfred Kinsey, who was switching his research from wasps to human sexuality, so Dr. Preer switched to genetics; I am sure there are some stories there. The first semester at Indiana I took a class on molecular mechanisms of evolution, and that was the first time I realized that molecular biology was more than a pre-med “weeder” class. It was clear that molecular biology could revolutionize evolutionary biology, and that’s when I started studying molecular biology for a reason, which led to being hired at Ames.

As an aside, I don’t know if you remember the coming-of-age movie, “Breaking Away” starring Dennis Quaid among others? I was in the crowd for the bicycle race scene while at Indiana. Anyway, it’s a very cute movie, and it was a fun October Saturday out of the lab. You should watch it.

When I returned to Indiana, I learned an enormous amount for a year or two. Sadly, Dr. Sonneborn developed pancreatic cancer, and I was one of maybe two grad students who was dispatched to sit with him in the afternoons. There are few more depressing ways to spend a Ph.D. than sitting with someone whom you admire so enormously and watching him waste away. In addition, I was teaching evolution in southern Indiana and had students who brought their ministers in to try to save my soul. Southern Indiana is far more conservative than northern Indiana such as South Bend where my maternal grandparents lived for many years. In fact, Bloomington is not that far from the former HQ of the KKK.

After Dr. Sonneborn passed away, it was time to leave. I had met Professor Annette Coleman of Brown University when she visited Indiana and was impressed with her brilliance and enthusiasm, so I called her and asked if it would be possible to transfer to Brown? Let’s just say I was flown out immediately to fill out an application and interview with the admissions committee, was admitted, then returned to Indiana to finish up the semester.

At Brown I was embedded in an algal lab, rather than a protozoan, because the chloroplasts were also of interest to me because of their role in the origin of eukaryotic cells, symbiosis, and in the horizontal gene. I told Annette “I’ll do anything you want me to do” and she said “well, I really like the project you’ve already come up with”, which was on chloroplast evolution. For my Ph.D., I was the first one to isolate the RuBisCO (ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase which is the major enzyme in photosynthesis; in fact, there’s more RuBisCO than any other single protein in nature.) Annette’s attitude was that I should have had a Ph.D. by then, and it was her job to make sure I got one. She was a fabulous match for me. I still run ideas by Annette, and polish up the iGEM team before they present to her, reminding them she is their “academic grandma.” A Ph.D. is the last of the medieval apprenticeships, so the student/advisor chemistry is critical. After graduating, I stayed at Brown for a short postdoc with another professor there, Susan Gerbi, working on the evolution of ribosomal DNA in yeast, which got me going in molecular techniques and in retrospect, fungi of a sort. I should add that Susan has also been enormously helpful critiquing our iGEM team before they go to Boston, as have several former members of my thesis committee who still are affiliated with Brown.

At some point, I met Andy Knoll, a very prominent micropaleontologist at Harvard, and he invited me to give a seminar on my thesis work on chloroplasts. When I finished, he said “Do you know that NASA would have paid for your Ph.D.? I was taken aback and probably said, “No, that’s the space agency, you’re confused”. Anyway, he corrected me by pointing out that NASA is interested in life in the universe, and since we only have one example, they fund a lot of early evolution. I suspected this for decades and I finally confirmed it: Andy gave NASA my name. And soon I was getting notices about the NRC postdoc program. In the meantime I had been recruited for an equivalent [position] with the Canadian government: there’s an NRC (National Research Council) lab in Nova Scotia that had a lot of top-rate phycologists. The labs weren’t supposed to share postdoc applications just like you wouldn’t expect an Ames applicant to get an offer from Goddard, but somehow an NRC lab in Saskatoon also had gotten ahold of my application, and that was actually my first offer. As I recall, the researcher from Saskatoon said: “It’s a great location: we’re only 3 hours from Edmonton!”(laughs) I did turn that one down. It was a really tough decision between NASA Ames and the NRC lab in Halifax, but in the end, I’m a U.S. citizen and I thought that I’d be more likely to be spending my career in the United States. But as it turned out it was a good thing not for the reason you think. The government in Ottawa changed the focus of the Halifax NRC lab about three years later from phycology to fish disease. So that’s how I ended up at Ames: I got an NRC postdoc with Chris McKay.

He’s kind of a hub, as we are finding out!

I was with Chris for a year in SSS (which no longer exists) on the fourth floor of building 239 (which does exist). After Chris moved to another branch, I was directly under Glenn Carle (the branch chief) for two years. So yes, I’m on my second tour of duty in Code SS. My postdoc according to the NRC application was to continue my work on the evolution of carbon fixation, which I’m still desperate to get back to. Most people don’t realize I have a photosynthesis background, but about every ten years someone invites me to talk about photosynthesis, and I think “do I have something new?” So, I ended up with three years of an NRC, studying microbial mats and the evolution of carbon fixation, which was a fabulous experience. It involved much more fieldwork than molecular biology, which was actually easier than some of the molecular work I was doing. And that was when molecular evolution was being taken over by DNA sequencing, which I stayed out of as I didn’t see how we could be competitive at Ames without a more serious investment.

So how did you end up becoming a civil servant, what are you working on now for NASA, and from the standpoint of the taxpayer, why is it valuable?

This is sort of interesting because it finishes up the story of my education.

Don’t leave anything out!

I know Glenn Carle tried to hire me a few times, but there wasn’t an awful lot of hiring in those days, and I don’t remember open searches. I did talk to Dr. Pam Matson quite a bit, who before moving to Berkeley, and Stanford was in SGE. Pam went to her Division Chief, Jim Lawless to speak on my behalf. Jim called me into his office and said: “I can have you in SG (Earth Science) by this afternoon”. So that’s how I ended up in SGE. Unfortunately, they didn’t have a slot either and put me on a contract.

So how did I get hired? In 1997 the annual meeting of the Society of Cell Biology was in San Francisco at the Moscone Center, so I had a poster there on the work my lab was doing on DNA damage repair in nature. Dan Goldin (NASA Administrator, 1992-2001) was giving the plenary. Of course, I thought, “I’ve got to go hear him.” The afternoon of the talk, I saw Dr. Harry McDonald (Ames Center Director, 1996-2002) and David Morse (Ames Public Affairs Officer) standing in the middle of the Moscone Center, looking alone, not knowing anyone but obviously needing to be there because of the Administrator. And I thought “What is the chance that I’m ever going to get to meet the Center Director? They’re just standing there”! So, I walked up to them and I said “Dr. McDonald, I work at NASA Ames” and he looked at me and said. “Well, then when the Administrator speaks, you must sit with us, so get there early”. I got there absurdly early and was able to chat with Harry and Dave. At some point, Dave asked me what I did and said, “So are you a civil servant or should I list you as a contractor in the Astrogram?” When I told him I was on a contract, Harry leaned over and asked, “Lynn, are you a cell biologist?” “Well, I think of myself as an evolutionary biologist, but in fact, I do have a Ph.D. in molecular and cell biology”. And he said, “So you could count yourself as a cell biologist?” And I said “Yes”. And he leaned over, and said: “You’re hired!”

This was the most unreal experience in my life. We were in an enormous room with literally over a thousand people, with Dan walking down the aisle with the press and the president of the Society of Cell Biologists. So, Dan walked down the aisle, turned to Harry, shook his hand, and Harry turned to me and said, “Mr. Administrator, I would like you to meet our cell biologist, Lynn Rothschild”. I’ll spare you the details about the press and photographers, but we then all sat down and all I could think is “what has just happened?”. At some point, Dan said to the audience “We’re very tight on slots, but I feel that biology is so important to the Agency that I have authorized Dr. McDonald to hire a cell biologist”. And then I realized what had happened. I found out later John Howe, who was the Chief Scientist at the time and had been advocating for me, had already given Harry my paperwork, as Harry would never just hire someone off the street like that, So, I went up to Harry afterward, probably shaking, and asked: “Were you serious about the hiring?” And he said, “Of course!” I was so astounded and grateful I said, “Thank you … sir!” So that’s how it happened and I’m probably the only civil servant who, within seconds of being hired was shaking hands with the Administrator.

So to your work now at Ames over the years, you’ve been here now for a while.

Yes, so I wear two hats, as you probably know. I’m an evolutionary biologist by love and training, so when the whole astrobiology thing was starting to hit in the late ‘90s, I was extremely excited (even for me) because to me it’s evolutionary biology writ large. With astrobiology, you’re no longer just talking about population genetics or small-scale phenomena, you’re bringing in the environment, and in fact, how do you get the environment that you have, and what’s going on in the future, and so on. So, when astrobiology started, I said to Dave Morrison, who was director of Code S at the time, “If there is anything I can do to help . . . “

One day in 1999 he walked into my office, which division chiefs and directorate heads don’t normally do. He told me “I’m thinking of having an astrobiology meeting. I’m going to be on vacation for a few weeks, and I want you to find a date for the meeting.” People said at the time, “Lynn, that’s just the tip of the iceberg”, and sure enough, when he came back he said, “I want you to chair the Local Organizing Committee”. The head of the Science Organizing Committee, Bruce Jakowsky, had a different conception, so between the two of us, and Greg Schmidt, Dave Morrison, and the huge organizational skill of people like Karen Bradford and Rho Christensen, AbSciCon (the Astrobiology Science Conference) was born. Rho came up with the name AbSciCon. I had lunch with Dave the December before our first AbSciCon, which was in April 2000, and he said, “I’m thinking it should be a small workshop, I think we’ll hold it to 50 people”. And I said, incredulous, “We already have 250 abstracts, so how exactly do you want me to work this?” In the end, we put no cap on attendance. It was crazy, we had it in building (N201, Syvertson Auditorium). At one point I knew how many seats were in every auditorium at Ames and that one held around 350, something on that order, and we had well more than that, and still people kept flooding in. People were calling from headquarters and asking, “Can we come tomorrow?” And I remember Jack Boyd begging me, “Can I tell them that it’s full?” And these were people like Jerry Soffen, so I said “I’m not going to be the one to say that. If you want to say it, it’s not on my head.” I remember that the fire marshal was upset, the place was so oversubscribed. At one point I said to Harry, “The fire marshal is going to kill me!” And he just grinned and patted me on the back and said: “Relax!” Oh yes – on top of it all, President Clinton landed at Ames the night before we started. There is a funny story about one attendee from France being lost on base, intercepted by the secret service, who then radioed the secret service on the tarmac with the question, “What the Hell is Astrobiology?” (DOI: 10.1126/science.288.5466.603). Well, it was an enormous success (see, for example, the write up in Science). I’m afraid that people forget that AbSciCon was an Ames’ invention. In the next two AbSciCons (2002, 2004) we put up tents for the talks as well as using Building 3. We put tents up in the hangar because, with the skin on, it had its own weather system and generations of pigeons lived there. It was a crazy thing, we had tents up on the parade ground one year. It turned out that an auditorium seating a thousand was just not available on the peninsula. I suggested building one at Ames as I really think it could be heavily used. Attention NRP folks: I still think so.

Anyway, one of the things I loved about running AbsciCon is that unlike NASA HQ concepts of Astrobiology which were linked to funding priorities, my feeling was that AbSciCon was the chance to show what the field could be. That’s why I brought in things like the influence of the environment on the evolution of human skin color and the cosmologists. And we were lucky that we had a few people tip me off to “hot topics.” I had a science organizing committee that had been the plenaries the meeting before so they didn’t have an ax to grind, but we did also have one of the senior editors of Nature, who tipped me off about the Martin Brasier article that was going to come out saying that Bill Schopf’s interpretation of the earliest fossils were mere artifacts. I had already invited Bill for a plenary, but then Oxford got wind of it and their PAO office called me and said, “this is not right, you’re picking sides” and so we had a separate session after lunch with the two of them debating. It was such a big deal the Oxford PAO called me back to say “We don’t want our man being put in some dirty, dingy corner”. And I felt like saying “This is out of a University that’s over a thousand years old?” “We do not have dirty, dingy corners at Ames!” (laughs). Anyway, it was enormously successful. People are still talking about that debate. Every two years AbSciCon kept growing. We had enormous numbers of people, close to a thousand I think, on the one where we had Steve Squires talking about the exploration rovers. Sadly for Ames, HQ realized how valuable AbSciCon was and took it for themselves. So, in the end, we ran AbSciCon 2000, 2002, and 2004. In 2006 AbSciCon was held in Washington, but I don’t think the new organizers realized how much work it was, so in the end, Karen Bradford, Rho Christensen, and I stepped in to ensure it was a success. And then it was really gone. I do think this was a shame because it was far more creative and innovative when Ames ran it. I would love to get it back to Ames, although it was three months of work every two years.

The other thing I did for the Astrobiology program was run an HQ-level office at Ames, the Astrobiology Strategic Analysis and Support Office. Its purpose was to foster the development of the field of astrobiology through:

- Development of unique programs to enable new astrobiology investigations;

- Integration of revolutionary technology capabilities into astrobiology instruments and missions;

- Development of the astrobiology science and technology communities through focused workshops, seminars and conferences; and

- High-leverage outreach opportunities to engage the public by the millions in the excitement of astrobiology.

During that time I was in Code D as a direct report to Center Director Scott Hubbard, and then Pete Worden. Unfortunately, it was also a time of shrinking budgets for Astrobiology, so eventually the office was dissolved and the responsibilities moved to the NAI.

I was looking for something of a high point in your science work.

We were doing a lot of work in extreme environments, as a way to have analogs for the early Earth because once you’re at really high salt or high temperature or whatever, you generally don’t have multi-cellular organisms. We did a lot of fieldwork in the salt ponds and intertidal in Baja California, the hot springs of Yellowstone, Bolivia, Kenya, New Zealand, and the radioactive springs in Australia, and various other places. We primarily did metabolic work and DNA damage and repair, unfortunately at the time, we didn’t have the sequencing skills every lab has today. At some point, an editor of Nature (magazine) contacted me and said: “we’re doing a series of articles on astrobiology and we would like you to write one on extremophiles and the search for life in the universe”. And at the time most people equated extremophiles with high-temperature archaea. And I said “That’s very kind of you”, and, with uncharacteristic modesty, “but I’m not really an expert on extremophiles, I just happened to go into these environments.” And they wrote back in their usual inscrutable way: “We like the way your brain works”. Huh? So, Rocco and I wrote that insight article, and it’s still considered the classic in the field, and why, to this day, I’m invited probably six times a year to give a talk on life in extreme environments and the search for life in the universe. I come up with different titles periodically and I keep updating it, but the outside world expects that I’m this walking encyclopedia on extremophiles, which is great fun, I mean everyone loves it. So you can’t beat it. And I’m hoping now to get some postdocs and return to extremophile work, HQ review panels willing.

So, the search for life that NASA is doing really captures to public imagination?

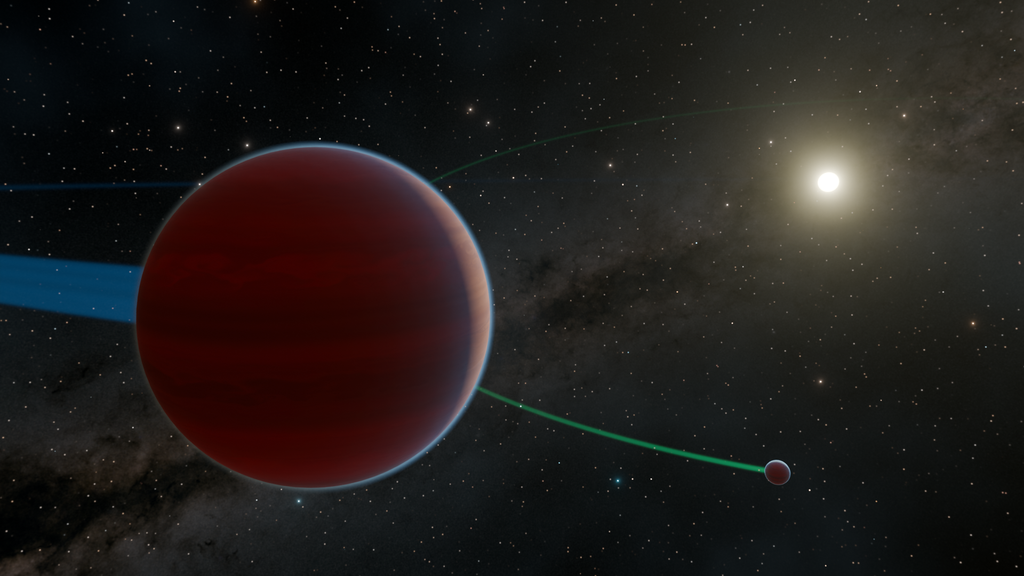

Absolutely! And my point has always been that we only have one data point, and that’s life on planet earth. What you have to do is understand what this environmental envelope is for life, and then map it to other places that might have the same sort of environment. But, of course, the envelope we have on earth is just the minimum. We know that it can happen because it happened. But it may be that there are other tricks organisms can use to push the envelope further, so that’s why right now I’m anxious to do that and add the synthetic biology component. The way I sort of jokingly put it is if I have a colleague who is an astronomer, and they say, “you tell me that life can only go up to 122 °C, but I have a perfect planet where the average temperature is 130 °C, do I have to cross it off the list?” No one wants to see an astronomer cry, so I would say “let’s see if we can make something that can live another 8 °C higher”. Synthetic biology actually first appeared at NASA in astrobiology documents.

What is a typical day like for you? Do you have typical days?

My days [contain] far, far too much paperwork than I would like, so I do try to do paperwork in the morning at home, let the traffic calm down and get a swim in, and then when I’m here I try to have an open-door policy. (Obviously, this interview took place before “shelter in place”.) And I didn’t even get to tell you about the iGEM Team. I’ve had that craziness in the summer since 2011. These groups of anywhere from 8 to 15 undergraduates, primarily from Stanford and Brown where I hold or held adjunct professorships. One summer there were 35 in my lab. But I try to keep it open door and I try to make rounds in the labs at least once a day and see what everyone is doing. I seldom do lab work myself, although sometimes I sit down with a microscope, and then you can write me off for some time because I can’t pull myself away. I’m still like a little kid, looking at protozoa.

So, if I can give the other phase of my life: I was doing all that sort of stuff and I would have been perfectly happy looking for Martians for the rest of my life, and then what happened is we got a different Center Director, Pete Worden. Pete met John Cumbers, who was a Ph.D. student at Brown, at a meeting where John had convinced him that synthetic biology’s new thing was going to be the key for human space exploration. And Pete in his usual way, said, “You are going to finish your Ph.D. at Ames” and thought my lab would be ideal because of my molecular background. In the meantime, Brown wasn’t too thrilled about him coming here, but it was the same department I had gotten my degree in, so they said: “Wait a minute, Lynn’s there, we’d feel better if John were in Lynn’s lab”. I knew none of this. And next thing I know I have a grad student in synthetic biology and I was told to start a program for the Agency! This is my life. So, Pete sent me along with one or two others from SC to Washington, I met with the Air Force, the Navy, NSF, NIH, DARPA. In fact, I ended up representing NASA on a White House (OSTP) working group, to write a report to Congress on the state of our nation’s capabilities in synthetic biology. There is now a new working group that I’m on again, to update it, which is cool to help advise on the direction of US research, meet and learn about programs in our sister Agencies and DOD, and occasionally get a trip to the Eisenhower Executive Office Building (next to the White House.) This has turned out to be a really wild ride because the synthetic biology of today is so much more advanced than the molecular biology of my former life. For example, when I was in grad school you could get a Ph.D. for sequencing one gene, and now we expect students to do more than one in an afternoon. It’s exciting because most people in synthetic biology come from an engineering background. Science and engineering are two different mindsets. As a scientist, you look at the world the way it is. For an evolutionary biologist, this means looking at the window at the amazing diversity of life and you think “Wow! This is really cool!” “How did it get there? How is it evolving? How does it work?” Engineering is totally different. You look out the window and you say “Aha, here is this amazing genetic hardware store! What can I make new with it?” That’s what engineering is, is making something new that is useful to humans. So now I feel like I’m a little bit schizophrenic: on one side my heart is definitely still in the astrobiology and understanding how we got to be what is. But then once you have the engineering skills you can make new things such as make a biological glue, a wire out of DNA, an on-demand pharmacy, structures our of fungal mycelia, or even a biodegradable drone, all projects we have worked on in my lab. Or for astrobiology, you can use synthetic biology to study not just what is here, but what I like to call, “the art of the possible.”

This must be what Steve Howell was talking about. He said to ask about your artificial sponge.

Well, remember I mentioned that I took multiple classes with the world’s greatest sponge phylogenist at Yale? With the ability to now both engineer cells and print them, a pet project Dr. Jessica Snyder in my lab and I would love to do is to digitize and reprint a sponge. Why not? A sponge is basically a pump without an on/off switch and no need for electrical input. And yes, we do have a stool made of fungal mycelia that you can sit on.

The field is at the point that we can do darn near anything – or will in the next few decades. But while I believe that synthetic biology is valuable for multiple areas for NASA and probably critical to long-term human settlement, it is an unusual technology for NASA in that we are not now, nor ever will be, the world leaders. Well, not unless you want to spend NASA’s whole budget times X. It’s an area where there are a huge number of startups, even Google X is trying to get into the business because it’s hugely important commercially. The big government players are NIH, NSF, and DoD. I will admit that, but my heart is still in the astrobiology, no question. So I try to combine them, so the answer is that in a typical day – I’m intellectually schizophrenic! (laughs). We’ve gotten to the point that some of the people, like Dr. Tomasz Zajkowski, are here for astrobiology, in his case looking for prion-like (amyloid) forming proteins in microbes, which could well suggest a role for amyloids all the way back to LUCA (the last universal common ancestor). It must have had a positive selection advantage early on. Is it because of its UV protection, as some people have suggested? it is sticky, is that what helps hold microbial mats together? So, then you take that, those are all science questions, and you repurpose them. OK, if it provides UV protection and is sticky, could we use it as a UV protective glue, say for the fungal mycelium? And that’s what I mean, it’s really kind of fun because our lab now mixes and matches disciplines and applications.

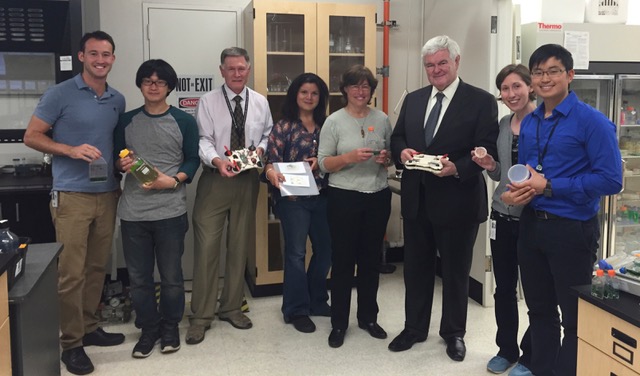

Each summer since 2011 I’ve been the faculty advisor of a synthetic biology team of about a dozen undergraduates and the occasional masters’ students through an international program called iGEM (international Genetically Engineered Machine Competition.) The students identify, design, and execute projects in synthetic biology, which are presented through a wiki, a 20-minute oral presentation, and a poster, the latter two in Boston at the competition in the late fall. This is very competitive so had created a high-energy environment in my lab each summer, but the result has been lots of cool proof-of-principle projects that have gone on to funded projects, Ph.D. theses, papers, press, and in one case, a request by the Secretary of Defense for the student slides! Not surprisingly, our team has won plenty of awards, and I am so proud of them. The 2019 Brown-Stanford-Princeton team was voted the best team by their 350 some peers, an award I’m particularly proud of. Come admire the plexiglass trophies on my desk. I would love to talk to anyone about the cool projects they do.

Actually, I’m extraordinarily proud of my students and postdocs. For the most part, they have been talented, enthusiastic, fun and like a family, each brings something new to the mix. So many have gone on and done wonderful things, and others keep coming back, which I also love. They are my academic kids. The fun thing is with our new virtual lab meetings, people are joining back in who haven’t been in physically at Ames for a while, so it is turning into an extended family!

You say that your career or your professional life has been kind of sort of what happened to you, not necessarily what you planned. What would you tell a young person who would like to be where you are, doing what you do? How should they pursue that, because it’s kind of just, you were in the right place at the right time, more than once?

I was very lucky, more than once. And I’m grateful to NASA because I wouldn’t have had quite the background in geology otherwise, or become a leader in the field of synbio. I always tell people, I was the least qualified person probably if I had been in the molecular department of a university. But I’m told that I’ve made great contributions to the field now, and I’m sort of grinning because it was Women’s Day last week and some biotech company tweeted “Hat’s off to the leading women in synthetic biology” and I was one of the eight! And that’s been retweeted and retweeted all weekend. I can’t believe it: I count in the top eight women! (laughs)

But anyway, what I tell students who are interested in being me, is that chance favors the prepared mind. This is another way of saying I have worked extremely hard to be ready to do whatever has come my way. And creativity is also key.

You had opportunities but you also took advantage of them.

But also, I had a very broad background in the biological sciences, and that’s why I tell people “I am the biologist’s biologist”. I can talk to you about photosynthesis, and prions, and a little about virtually anything else in biology.

So, you’re positioned to take advantage of opportunities that come, a wider variety of opportunities that come.

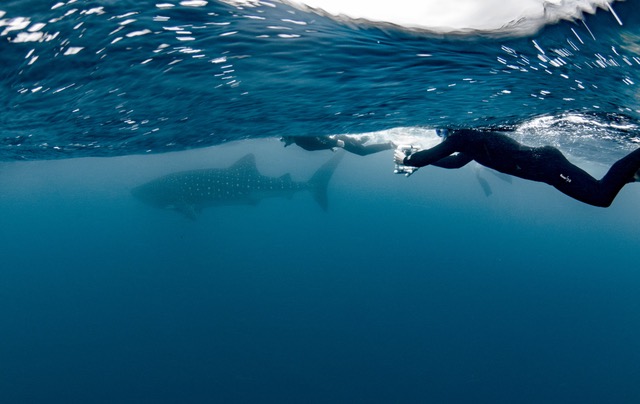

Right! So what I always tell people is, if you want to be me, you’d better have a broad background, and get it early so you can speak multiple disciplines like a native and approach them like a professional. I’m still more comfortable speaking evolution than talking about obliquity. Take at least the introductory and preferably one advanced class in as many of these scientific disciplines, geology, and so on, I end up giving departmental seminars now in geology. I could well be the only one in SST who has never taken a real geology course, which I regret. Chemistry and physics, biologists have to take, but geology is something we didn’t, much less planetary science. It does help to have a feeling for organisms as life is more than E. coli, rats, and Arabidopsis. For fieldwork, stay in shape – yes swimming doesn’t hurt and it keeps me sane. Both astrobiology and synthetic biology also require some background in the humanities – especially philosophy and ethics. History is always good. And finally, you have to be able to communicate, to excite your peers, students, and the public at large. I don’t know if you know this but I got an award from the American Humanist Society a couple of years ago, which I admit was a complete surprise but am very proud of.

I saw that that was one of your awards.

Thank you! The other thing is that I’m able to switch fields. I’ve been lucky that I’ve had the civil servant position so that I don’t have to worry about tenure. That does allow you to do things, but when you switch fields (well, not really switch as much as accrete), you learn new things but build on your strengths. When I started up the synbio program, I was looking for where NASA and I had the strengths, and that’s what I put in the report to Congress. At the national and international levels, NASA has strengths in the origin of life research and life in extreme environments. Both areas can be of great use to synthetic biology so that is what we bring to the table. Then we move on from there. I think that one of my strengths as a scientist, besides being broad-based is creativity. And that’s truly marvelous: being able to say “Oh, wait a minute: if the prions do this, maybe we can use them for that”. Or “If the filamentous fungi do that, maybe we could also do this”, you know putting things together that maybe other people have not seen. Diatoms make these intricately beautiful frustules out of silica. Integrated circuits have fancy patterns made out of silica. Could we use diatom frustules to make an integrated circuit? I love the new ideas and coming up with new things, getting them going, and then get other people to march through development.

So, switching a gear here, what do you do for fun? We’re talking about hobbies, etc.

I come to Ames for fun, is that the correct answer? I work for NASA for fun.

I saw a picture of you with bagpipes, so I thought you might go there.

But it is kind of my life, I’ve wanted to be a scientist since I was eight years old. There have been a couple of times that I almost got full time into administration, but I always stood up and said, “If it means giving up research, no”. If I lost my lab it would be like cutting off my right arm. It really is my life. But that being said, what do I do for fun? There are three things, I guess, besides the fact that I have two absolutely wonderful children, whom I adore. Both of them are working on their Ph.D.’s and both have been in and out of Ames, but my daughter, in particular, was here last summer working with Mark Ditzler. They were born at the time I was in Code SG (Earth Science) and Jim Lawless (Earth Science Division Chief) said that the children belong to the division of the mother, not the father! (laughs). Now that we’re both in SS it doesn’t matter but for the record, they were born into SG. I’ve been interested in music since I was very young, actually, I learned to read music before I learned to read. I started on the recorder. I grew up playing the violin, the piano, and the recorder, which I played in various groups over the years. And then I taught myself guitar and banjo and this and that. I’ve always really liked Celtic music. I don’t know if you know that Rocco is the only member of the family who was admitted to music school. He started off at the University of Colorado music school. He’s a clarinet and saxophone player but ended up switching to biology. Anyway, both of us had a music background and I like Celtic music, so when the kids were very young, we took them to some of the highland games in the Bay Area. The big one was in Santa Rosa at the time, it’s now in Pleasanton on Labor Day weekend. And Kyle was about this big (gestures with hands) when he announced he wanted to play the pipes. And I think it’s partly that has was a small kid and bagpipes are big and powerful. I told him “OK, but I’m not paying someone else to teach you to read music. I will teach you the recorder” and he probably thought I was half-joking, but I added, “I’m going to take lessons with you.” Anyway, he dutifully learned recorder and how to read music, and when he was 9 years old, he said “Mom, you promised” so I called the House of Bagpipes in San Francisco. It was owned by someone named Lynn Miller, and his wife’s name was Gail, and my sister’s name is Gail (I’m the oldest of 5 kids and I should say we are all crazy in different ways). So, he said, “Well, this is the person who is closest to you. But if you want the best, it’s Bill Merriman in South San Francisco. So, Bill took us on and Kyle was considered a prodigy from the first day. I went along but he normally starts with kids, I’m the only adult he ever taught who lasted more than a week or so. I’m still playing in the Prince Charles Pipe Band and Kyle is now playing for St. Laurence O’Toole pipe band in Dublin, which has come in third in the world the last two years but has been dominating the competitions this year. Two or three times in my piping career I’ve been caught by someone at Ames who admitted that they saw me in a kilt and playing pipes, but I always worry when I play in a parade that I’ll be spotted!

Well, speaking of that image that I mentioned . . .

But the other thing I do is swim and I also love canoeing. I was a camp counselor for a long time teaching camp craft, canoeing, and swimming. My other proud accomplishment is (pointing to a drawing in her office) . . . my father drew the policeman. My sister is the artist, she drew the dinosaur. Anyway, I was the youngest Junior Maine Guide (JMG) in the country in 1971. This involved passing a series of tests at a four-day testing camp on the Rangeley Lakes chopping down trees, first aid, map and compass, timed fire building, and all that stuff. I needed to take lifesaving to teach so I took it at the YMCA in Greenwich when I was 15. There were a lot of guys in the water polo team taking the same class and it was obvious after the first class, that I was going to drown if I didn’t start swimming laps. So that’s when I really started to get into it. So that’s why I was nervous about the noon (appointment time for this interview) but I wasn’t so nervous today because the pool was 73 degrees this morning, so I’ll go swimming at 3:00 o’clock. That’s why usually 12-1 pm is a sacred time because I’m out at the pool. Now that the Ames pool is (temporarily?) closed, non-swimmers should know that swimmers don’t just quit swimming; we need to find alternate pools taking time away from Ames. Just saying…

Year-round?

Oh yeah, oh absolutely! I’m usually there maybe four times a week and that’s why I’m sort of antsy about any meetings or seminars at noontime; now my kids have got me lifting weights as well. And the other thing is we have is a house in the woods, so we’ve done a lot of chopping down trees and planting. This is the end of the season where I move around a little, with young Douglas firs and rearrange the trees and that’s why I sort of hobble sometimes on Mondays.

Well, like I said if there is an image, a space image or image of your career work or something that represents one of your interests or something that we could put on here.

Well, there was no picture of it but there was recently the Apollo 11 anniversary and I’ve been on a couple of those panels, and I talked to a man who said “Well, I was the pilot of the helicopter that picked them up” and I was sort of the public relations woman, and they said “Where were you?” and the answer is I was at summer camp and I was 12 years old and I remember not thinking I’d ever end up at NASA but being really, really excited about Apollo 11. I begged and begged the counselors, I mean this was out in the woods, but surely someone can find a television. I know there are electric sockets in this building. And it was interesting because the director at the time, it was one of the first camps in the country and I could tell you about the whole history of the American camping movement, but anyway this was in Maine, it was in the middle of the night and I was twelve, and she finally made the correct decision that this was one of those things that everyone should see. So they found a little black and white television and everyone was in their pajamas and we sat there and watched, and I think a lot of the kids weren’t that interested. It was a little television and you’ve got 200 and some people crowded around, but I could not move and bless her heart, that camp director, who was probably in her 60’s at the time understood, and she sat there with me as long as I wanted to stay, it was probably after 2:00 in the morning. And I was absolutely transfixed. Since then I’ve met Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong, I met Neil at JPL. I knew he was going to be there for the NASA Advisory Council (NAC) meeting, where I had been invited to testify about the Astrobiology program. There was a bus tour of JPL, so I threw my stuff on the ground and as I was standing up, I realized there were two legs right in front of me, and when I was halfway up, there was his name tag, and I thought “Oh no!” So, what do you do in a situation like that?”

Introduce yourself?

I stood up and it turns out I did what everyone else did: I looked him in the eye (sort of) and I asked: “Can I shake your hand?” And he said, “Of course”. And we had a nice chat.

Do you have a favorite quote?

I usually go with Darwin, “There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.” (The Origin of Species: first British edition (1859), page 490)

But recently I saw a marvelous quote of Einstein’s at Newark Liberty International airport that is spot on, “Imagination is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited. Imagination encircles the world.”

Well, your passion and your enthusiasm are just wonderful.

We all have irritating moments but my life wouldn’t have been what it was if Harry hadn’t hired me into NASA, and Pete introduced me to synthetic biology.

Interview conducted by Fred Van Wert and Sara Rojo on March 12, 2019