We’d like to start with your childhood, where you’re from, your early family life, if you have any siblings, what your parents did, and especially how early was it in your life that you developed the interest that led to your current career?

I’m the middle of three children. I have an older sister and a younger brother. We were all born within one year of each other, so we are a tightly packed group. I was born in Teaneck, New Jersey, and spent my formative years in New Jersey until I escaped to college and then kept on going! (laughs) My dad was a pharmacist and my mom was a registered nurse. My sister today is a pharmacist, following in the family business. My brother is head carpenter at the hospital, named Holy Name Medical Center today, in Teaneck, New Jersey, where I was born, my brother was born, my sister was born, my father was born, and my father and my mother met, in a hospital romance! And now my brother works there!

Well, don’t let them ever tear that down! (laughs)

Back in high school, I used to volunteer there as a candy-striper. Nowadays the more gender-inclusive name volunteer is used for that kind of community service. As a child I was very studious, I liked school and learning. I liked science, I liked math, I liked all the subjects. I recently uncovered some notebooks that I kept. When I got hold of a small telescope, a refractor, as a child, I did these plots of the moons of Jupiter and the constellations. I have a fond memory of my seventh-grade science teacher, who showed me how to read the skies at night. I’m very grateful for my science teachers who encouraged me because I had a lot of questions, often questions that they couldn’t answer but they were always encouraging. So, all throughout my schooling, I was a very inquisitive child. My childhood dream, and my current adult dream, is to become an astronaut, so I’ve been applying, at every opportunity since I became eligible. I told them in my most recent application that maybe they would want a mature woman now since I am technically above the statistical average age of an entry astronaut candidate. To me, an astronaut is the ultimate ambassador – ambassador of science, engineering, exploration, communication, education – who can cross barriers, inspire, and evoke change. I remain hopeful to achieve this dream and be able to give back to our society even more than what I am achieving now through my science research and science communication efforts.

That’s wonderful!

Meanwhile, I am fully committed to my Plan A2, what folks call Plan B, as a professional scientist. Growing up I was very interested in any science, learning about how the world works and everything in it. I just kept on learning and figuring where to go from there. I was just very curious.

You’re not the first researcher we’ve talked to who got a telescope as a young child and was able to see the moons of Jupiter and Saturn and that was sort of an entryway to pique their curiosity and lead them down the road of science and astronomy and so forth, so you’re in good company.

Yes, and I also collected rocks, leaves, flowers, worms, and other things in the backyard. I was sort of a collector of natural things but I didn’t go into those fields.

No, and that’s OK, it’s all science. So, then you went to grade school and high school in New Jersey, is that correct?

Yes, I grew up in New Milford, New Jersey for my first 13 years. I went to Saint Joseph’s grammar school in Oradell, then we moved as a family to Westwood, New Jersey, and I attended Immaculate Heart Academy in Washington Township. So, we all stayed in the same county. The towns of Teaneck, New Milford, Oradell, Westwood, Washington Township, were all in Bergen County, in the northeast corner of New Jersey.

So, at some point then you needed to choose what university to go to and what to major in. Can you talk a little bit about your education through your Ph.D.?

At an age of 17 or 18, when it was time to choose colleges, I experienced what it’s like to switch to a Plan B, or Plan A2 as I like to say when things didn’t work out. I had been selected to go into the Air Force right after high school through an ROTC (Reserve Officer Training Corps) scholarship. I was very excited as it would help the family in funding my education. However, my scholarship was withdrawn from me through means I never understood. What was interesting is that it opened the opportunity to switch majors. The ROTC scholarship required me to be a mathematics major, which would’ve been perfectly fine, but I fell in love with physics at Johns Hopkins University, so I switched to a physics major. When deciding on colleges, I had never left the East Coast. In fact, I had never been outside of our time zone! I took a small step. I wanted to get far away from home, such that I couldn’t come home on the weekends, but I wanted to be close enough to home in case I had to. So, I had like a 300-mile radius, for colleges (laughs). I settled in Baltimore, Maryland, which was a good five-hour drive from New Jersey. I have treasured memories of my dad packing up the car and driving me down for the school year and then I would take the train home for Thanksgiving and Christmas. I enjoyed being away from New Jersey at that point. I chose Johns Hopkins not for any particular reason except that it was within the few hundred-mile radius! (laughs) It was a beautiful campus and at the time it was conducive to my ROTC scholarship but then when that was pulled out from under me, I revectored myself and found a home in physics at the university.

I was also in Air Force ROTC so I’m interested in why you joined. Was it because of your interest in flight or aeronautics? Or was it because of the stipend they paid?

In high school, I was a member of the Civil Air Patrol. I rose in the ranks there and it was a fun club to be part of and it was getting me excited about aeronautics and space. I was just a curious kid and it suited me more than, say, the Girl Scouts, so I joined the Civil Air Patrol. It was through CAP that they suggested I go for an ROTC scholarship but then that kind of got pulled out from under my feet and I wound up becoming a physics major and following a different path. I am the first person in my family to get an advanced degree. My father did have a bachelor’s degree and my mom had a nursing degree, but amongst my elder relatives, no one had a master’s or a Ph.D. Well, I do have a first cousin once removed who is a lawyer. (laughs) When I got to college, I learned that there was this whole world ahead of me that I could pursue academically, get a master’s and a Ph.D. in a particular field.

Was it in astrophysics or just physics in general?

Physics.

For both your undergraduate and your Ph.D.?

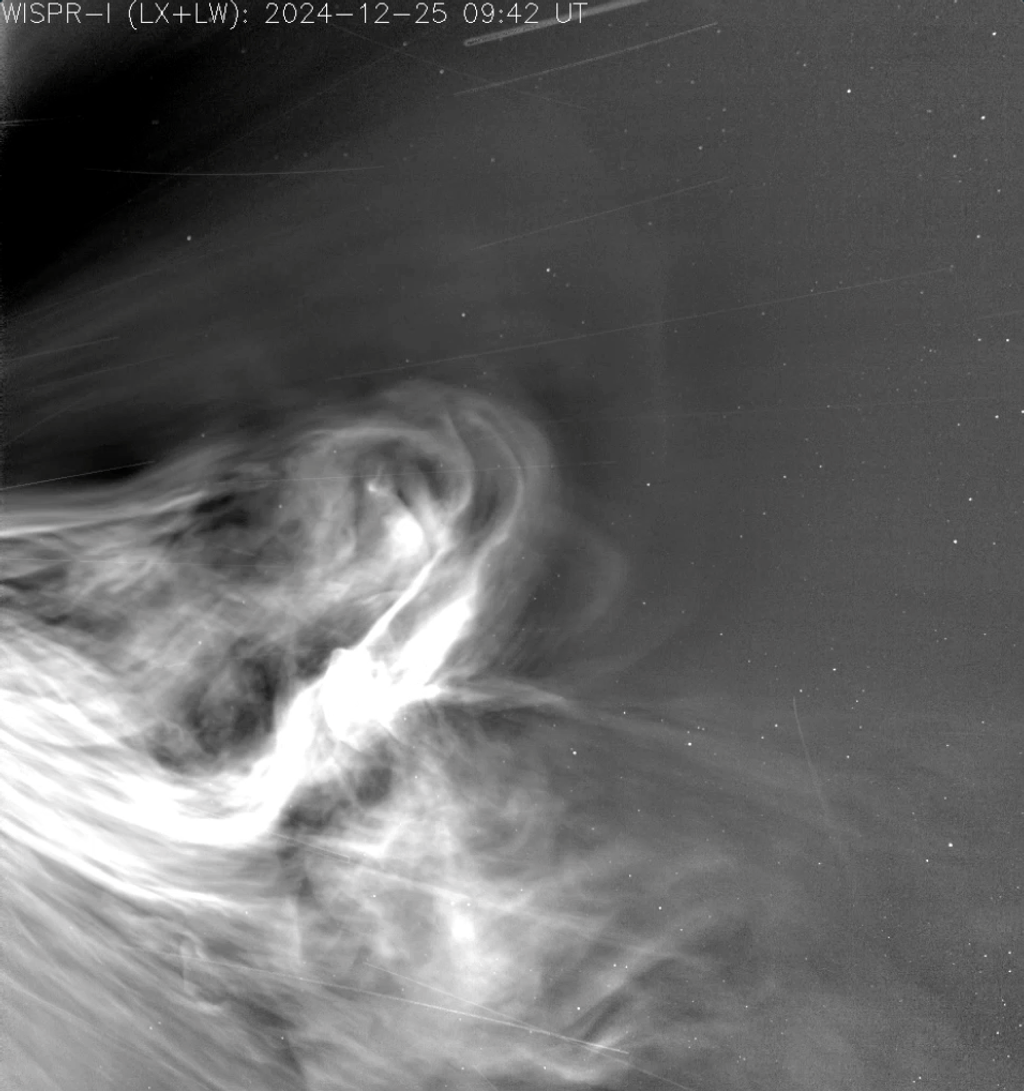

My bachelor’s degree is in physics. My Ph.D. is in astronomy. During my undergraduate years studying physics, I did a lot of different research projects and I gravitated toward astronomy research projects, probably because astronomy was a hobby growing up. I was in an undergraduate research program called SURAP (Summer Undergraduate Research Assistantship Program), and in ’92, which was between my sophomore and junior years, I crossed my first ever time zone, at age 20, and on my second plane trip, I went to Wyoming! I spent the summer there at the Wyoming Infrared Observatory. That’s also another crossroad in my life. I had signed up with an advisor for Plan A and then it soon became Plan A2 (laughs). Plan A was to study the moons of Jupiter using a new technique, speckle interferometry, that was being pioneered there. But for various reasons that project got taken away from me, and I found that summer teaching myself optics and this is the beginning of how I got into instrumentation. It’s one of these cosmic changes that you didn’t expect. That summer I designed an infrared camera, which eventually got built years later. Looking back, it was that summer that I cut my teeth on instrumentation for astronomy, applied astronomy in a sense, applied physics for astronomy: sensors, telescopes, that sort of thing. That summer experience opened an opportunity and I spent the next two summers working at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center as an intern. At Goddard, I built a mid-infrared camera to study the sun, which we then put on Kitt Peak (observatory) in Arizona a few years later. I’m grateful for my Plan A2, and although it was an experience that wasn’t expected, it led to more of these applied research internships and solidified my physics training, applying it to astronomy, which I loved as well, but in an active, applied way.

It sounds like going to Johns Hopkins put you proximate to Goddard, which was a good connection, so these things do tend to work out, and that’s an interesting story. Then you pursued your Ph.D. at Cambridge? Can you tell us a little bit about that?

Yes, I was a recipient of the British Marshall Scholarship. Although I was a recipient of several international scholarships for post-graduate studies, winning the Marshall was extra special. My next chapter took me to Cambridge, England. For the first time ever, I left the United States.

Congratulations! You crossed several time zones!

Yes, I crossed several time zones! And there’s kind of a fun story about that. I won the British Marshall Scholarship that’s named after the Marshall Plan, celebrating the special relationship between the British and the Americans after World War II. My scholar class year was the fortieth anniversary of the scholarship and they sent all the scholars over on Queen Elizabeth 2, the ship. So, my first trip to Europe was, not by plane, but by boat!

I would love that. I once had an opportunity to come back from Europe on either an airplane or a ship and I chose the airplane. And I really have always wished I had chosen the ship!

It was amazing! And, of course, as we transited the time zones, we were flipping our clocks at different times, over a five-and-a-half-day voyage. I guess I’m fascinated by time, as I’m thinking about it. Anyway, I wrote a journal about my voyage and at the time I put my journal up on the web. This was before blogging was popular. It was just basic HTML, but my story got picked up by an exhibitor in New York City and he wanted to feature it as part of the Cunard exhibit on “Journals throughout the Decades”. I was featured as the entry for the 1990s, as a young, aspiring astronomer going to Cambridge, which is, of course, a world-renowned center of astronomy. My journal entry is now featured as part of Cunard’s history. But what’s even more fascinating is, a few years ago, I got this email out of the blue from a professor from Gottingen, Germany, who wrote “You don’t know me but my wife and friends and I travel across the ocean on the Queen Mary 2, back-and-forth from New York, and I noticed your picture and journal in the hallway of the Queen Mary 2”! Well, I have not yet been on the Queen Mary 2, but I make trips around the world now, at least my two-dimensional self does. (laughs)

You’ve already had more than your 15 minutes of fame, that’s for sure. Did you choose, on that first voyage, to go by ship rather than by plane? Was that your choice or was that part of the package or something?

No, that was part of the package, that we would all go together as a group and we all bonded that way, too, the scholars.

That’s an amazing idea, great! So, you went to Cambridge and got your Ph.D., and then at some point, take us down whatever the path was that got you connected to NASA Ames.

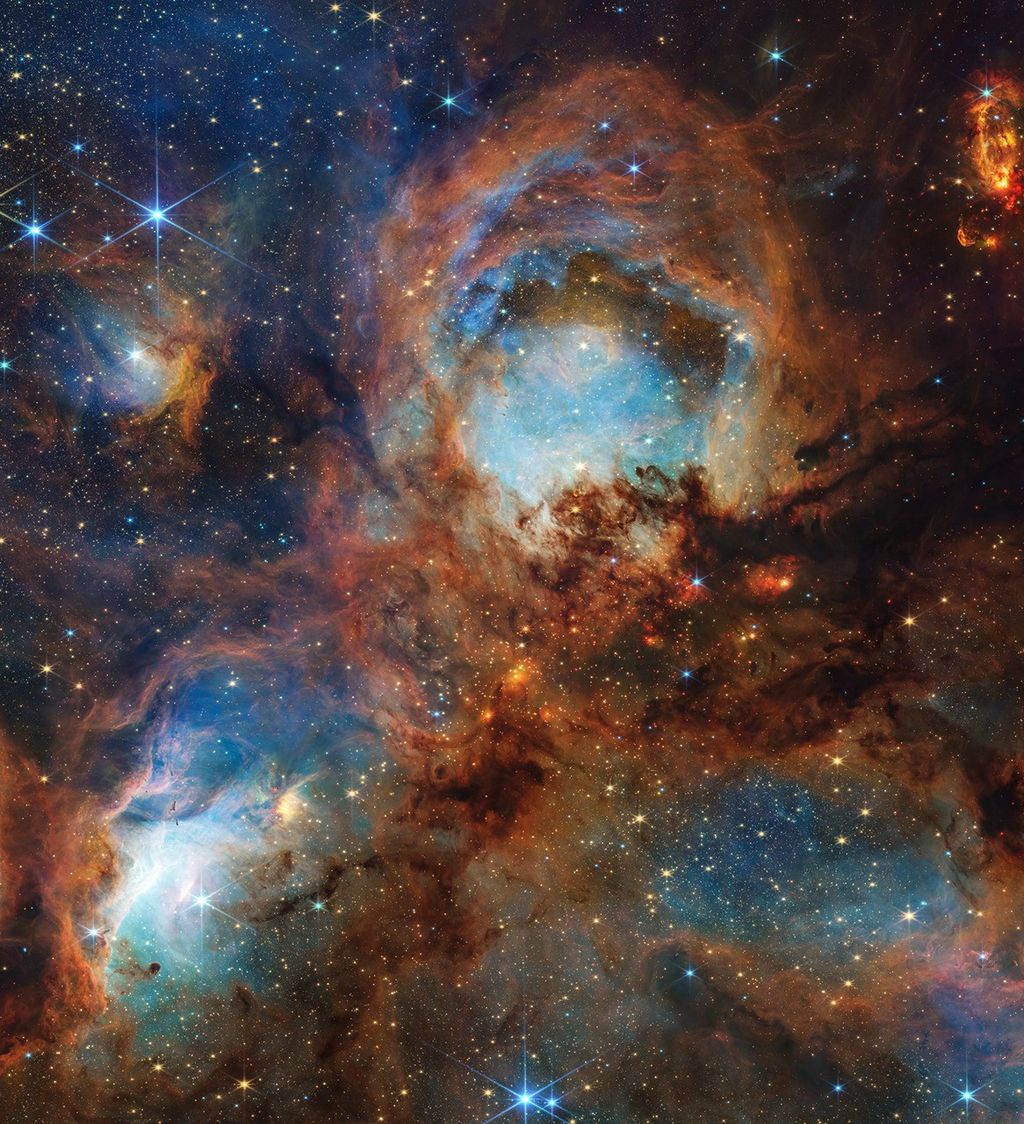

While in grad school I learned that what comes next after finishing your Ph.D. is to follow it with a postdoctoral position. Of course, I wanted to someday work for NASA and be an astronaut. But in 1998, I landed a postdoc at Steward Observatory in Tucson, Arizona, working with George and Marcia Rieke, and Jill Bechtold, in infrared astronomy. One project was for George Rieke, who was the PI for the MIPS (Multiband Imaging Photometer for Spitzer) instrument for the Spitzer Space Telescope, known at the time as SIRTF, the Space Infrared Telescope Facility. MIPS was an instrument enabling far-infrared astronomical observations, with detectors cooled down to two degrees above absolute zero Kelvin and whose filters had to be made from mesh material rather than some sort of glass type. It was a fascinating instrument to work on.

For a second project, I did design work for what would become, and what is now the James Webb Space Telescope, but was called at the time, the Next Generation Space Telescope. This included a trade study on what the instrument complement should look like. I’m pleased to say that some of my work influenced the current design of the James Webb ISIM, the Integrated Science Instrument Module. When working on that project, that’s where I met Tom Greene, who was the branch chief of SSA (Astrophysics Branch) at NASA Ames. And he was very impressed with the work I did.

It was during this time at Steward where I cut my teeth working on space-based instruments for the very first time, something I was eager to do because my Ph.D. thesis focused on a ground-based telescope instrument. For my Ph.D., I built a spectrometer for the United Kingdom Telescope Facility on Mauna Kea. I had other experiences as an undergraduate working on cameras on various ground-based telescopes in the U.S., but I hadn’t worked yet on space instruments.

Towards the end of my postdoc, Tom Greene, who was involved in the JWST project, said to me “You should interview, we have a job opening”. I smiled and thought, “Ooh, I could go work for NASA!” So, how did I get to work at NASA? It was luck and timing and just doing my job. I got hired as a term employee for two years. I was sad to leave the MIPS project because they wanted to extend my postdoc. The MIPS team went on to be very successful with the launch of SIRTF a couple of years later and it was still a great learning experience for me, cutting my teeth on that. I joined the Ames family in September of 2000, nearly 21 years ago! (laughs)

That seems like only yesterday! And you must be on pins and needles with regard to the James Webb because I believe it’s scheduled to launch later this year, I think in November?

The launch was supposed to be on Halloween, but I think they moved the launch date to December. The entire astrophysics community has been waiting for this amazing machine. Although I haven’t been involved with it in its final configuration, it was nice to be part of it 20 years ago when we were coming up with concepts for what the community needed the observatory to do. And although I’m not intimately involved with any of the instruments right now, I did test several of the detectors when I worked in Craig McCreight’s lab at Ames, now Code RE, then Code PMF. Some of my early projects there involved the down selection of the mid-infrared detector material for a range of different detector types. We, as a government lab, were able to show an independent assessment because if you relied on a particular PI at a University, who was promoting a certain type of approach, or a company that wants to sell their product, the value of a government lab is that it can do an unbiased measurement approach. So, we did a series of tests at UC Davis with the cyclotron. We’d put our dewar in the back of a van and drive it up to Davis and bombard it with protons, to see the effects of radiation and those experiments led the down select, or the decision making, of which devices were going to fly on James Webb. But yes, I am very excited about this new chapter that’s about to open and a lot of people are going to be holding their breath when it comes time for that Ariane-5 launch from French Guiana later this year. (Interviewed in August 2021)

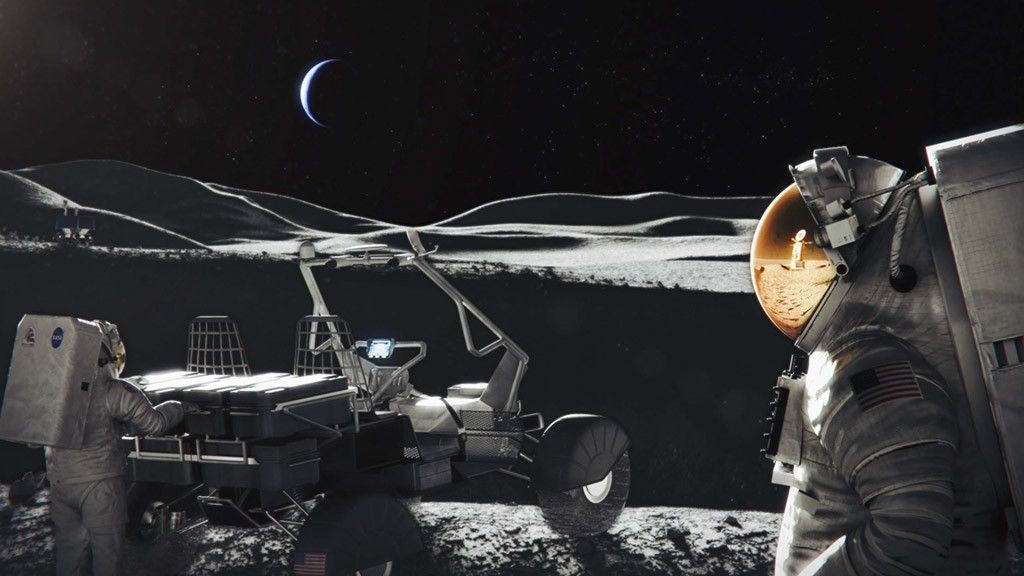

No question about that. Some of your projects are yet to be launched, such as VIPER, which is due to launch in 2023, but you also have an impressive number of missions that you’ve been involved in already, including SOFIA and LCROSS. Are there any high points or maybe even discoveries or new understandings, that have come from work in the programs that you’ve worked on? Discoveries or important research findings?

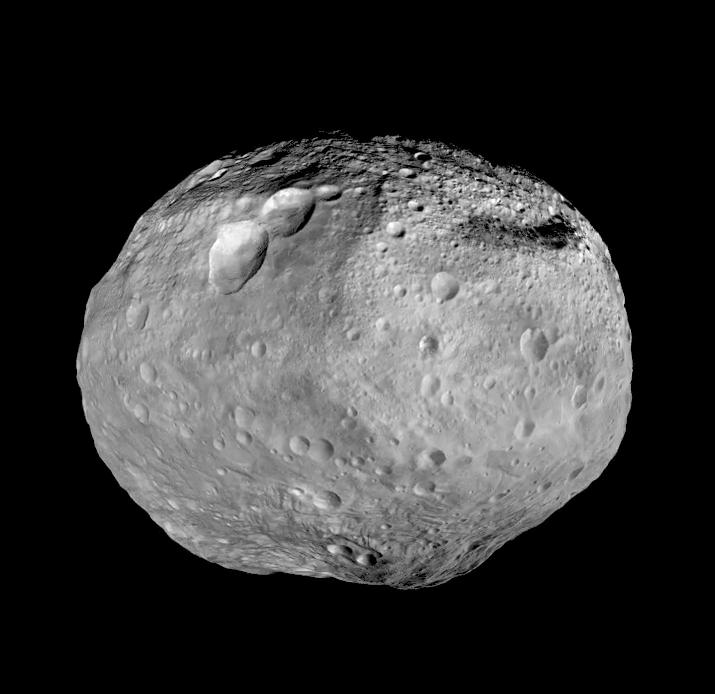

Well, my role at NASA has been gravitating toward where I find myself able to contribute the most. Because of my love and affinity for instruments and detectors, it leads me to roles such as instrument scientist, payload scientist, and then more recently project scientist or mission scientist. Anything that I can claim to be a discovery is never mine, it’s always as part of a team. Looking back at the variety of things, the different instruments that I helped build, or helped make sure that they met science needs, led to discoveries. Yes, I’ve been working on a wide range of different missions and different science areas from interstellar astronomy to lunar science to Pluto. The LCROSS mission, a lunar impactor, was very special to me. It’s a long time ago now but it was an exciting new way that NASA was doing missions, Class D, before Class D was a NASA classification, although the Air Force was using the Class D for years. It was exciting to be part of paving a new pathway. Now, 12 years after LCROSS, being on the VIPER lunar rover team, is a wonderful bookend to the LCROSS experience. So many lunar science community discussions right now hinge on that LCROSS discovery that remains to this day the only in situ measurement of water ice at the lunar poles. With the LCROSS discovery, we began an exciting new chapter in the textbook about what we know about the Moon.

And it was a complete surprise to find that the moon, which everybody thought was dead and dry, actually had volatiles on it.

Yes. It’s been amazing to observe the evolving story of lunar water. Last year there was another neat lunar water discovery. I wasn’t involved in Casey Honniball and her team’s using of the SOFIA observatory, but she did use the instrument that I helped build: the grism mode of FORCAST (Faint Object InfraRed Camera for the SOFIA Telescope). Years ago, I was the lead of that project, along with Luke Keller at Ithaca College. We put basically a second-generation instrument on SOFIA even though it’s still considered first generation. So, let’s call it first-gen plus! (laughs), an augmentation. We added a spectroscopic mode to the existing camera using grisms, which is sort of a prism with a grating on it. The grism mode of FORCAST is another project I’m very proud of. What is interesting is that mode was used recently to confirm the presence of water ice on the Moon in sunlight regions. So that’s an amazing and a very clever use of an existing instrument originally built for astrobiological studies of stars and the interstellar medium. It’s pretty neat that I’ve had my hand in two instruments that were involved in revealing the story of water on the Moon.

And now, in 2021 on VIPER, the lunar rover, I’m working on a third lunar instrument, NIRVSS (Near InfraRed Volatile Spectrometer System) on the VIPER payload. I am also serving as a deputy project scientist across the mission. It’s nice to be working again on pushing our knowledge to better understand this evolving lunar water story.

One of our questions has to do with what a typical day is like for you. I think of you essentially as an instrument developer, instrument designer. Is that done mostly on your computer or is it done in the lab or the machine shop? Do you work with Emmett? How do you come up with these instrument ideas and develop them into a working product?

Well, it depends upon which day of the week you catch me. If you’re coming up with a conceptual design then you’re spending a lot of time designing it on a computer. Sometimes you want to make a prototype and that means having access to a fabrication lab or a person like Emmett, a true treasure to our division, to make or modify something. Sometimes you’re not doing it yourself, you have a team and for certain things you’re not doing it in-house, you have to outsource it. During testing, you’re using laboratory spaces to carry out tests and sometimes you need to go further afield, such as for our radiation testing of the detectors we went to the Davis cyclotron since we couldn’t do here on base at Ames. Other times we would bring our instrument to another company for other tests. So, it depends. The job involves desk work, lab work, travel to other facilities, that sort of thing.

What do you enjoy most and least about your job?

I enjoy most the variety. I’m glad that I’ve been fortunate. Having the ability to work on the different missions and support the agency’s goals of exploration of the universe is very enjoyable. I like the flexibility, the range of jobs that a person with a physics and astronomy background can do for the Agency. I also think that you can reinvent yourself a lot if the place allows it and you are open to being the new kid on the block. More recently I’m working on planetary science missions like New Horizons and missions studying the Moon. I giggle when I reflect I had never looked at the Moon scientifically at all as an infrared astronomer. The Moon was a foreground object, and you were looking at other things like stars and galaxies (laughs). These past few years learning about how planetary missions are designed, it’s been so very different from astronomy missions. You operate the detectors differently. For example, astronomers like to stare at one place for a long period of time, like the James Webb is going to do, and for the instruments to operate stably you must have the lowest dark current and the lowest background possible. But with planetary science, you’ve got so many photons, and usually, some thing or things are moving! You must have detectors that read out really fast or you must deal with a variety of image scales. Today, on my current assignment, I’m working on a rover! I’ve never worked on a rover before and that’s another different challenge and a cool opportunity. So, there’s that variety aspect I enjoy. The downside of the government job is, well it’s feast or famine. It comes down to whether there are funded space missions. The Agency really doesn’t run as many missions as it used to. So, these true flight missions are few and far between. During those slower times, between funded flight missions, I’m looking at mission concepts and I’m always adding to the toolbox learning something new. Sometimes it’s just a waiting game.

That’s an insightful answer and I know exactly what you’re talking about.

I mean space exploration is for the patient. As I tell my impatient patient self. (laughs)

That is true. You’ve already answered one of our questions which is: if you weren’t a NASA research scientist what would your dream job be? You’ve already told us you want to become an astronaut and we commend you and wish you well in that pursuit. We hope that can work out. What advice would you give to someone who would like to have a career in science or tech or maybe work for NASA, as you have?

First, be flexible. A lot of times your plans don’t work out as you expect. They will become a Plan B or plan A2 or plan A prime whatever you want to call it, and might turn out to be as rewarding, or even more rewarding, so be flexible. Second, stay curious. When you are curious you are always learning. Learn as much as you can because you never know where that learning might come in handy. I’m often surprised that I dip into my toolbox for something I learned eons ago and it proves useful for the team. Third, recognize that you do have a voice at the table. I’ve gotten into the habit of calling myself a system scientist like they have system engineers. I might not be an expert in any one field, but I’ve been able to adapt and be flexible and be curious, and then it turns out I have a contribution to make because I come from a different approach to solving problems. Finally, be patient.

Most of those we’ve interviewed, their paths has been something of a zigzag, with a lot of plan B’s and even C’s, but they have said what you said: just be persistent and keep the overall goal in mind, don’t get sidetracked, keep working toward your dream and it may not work out exactly as you envisioned it, but it will work out very satisfactorily.

In a STEM field, you are working with intelligent, creative, motivated individuals, and your interactions with them will bring you to places that you didn’t experience, so it’s rewarding in that way, and it helps you grow as a person. It’s very fortunate that choosing a life in science is just a never-ending adventure in exploring and questioning, thinking about things, and solving problems. The Agency has a lot of tough problems ahead waiting for motivated, smart, and interconnected people to help solve them.

Moving a little bit away from your work at NASA, what do you do for fun?

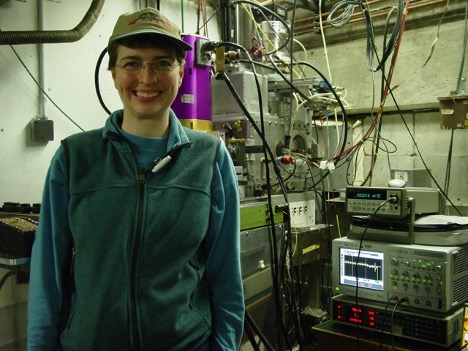

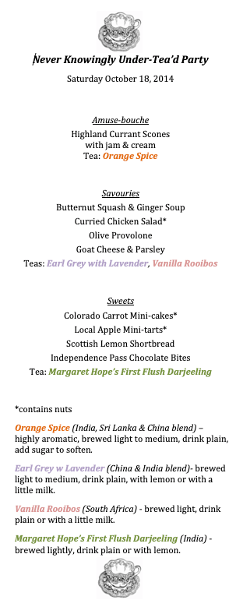

Well, it’s varied over the years. More recently, ever since I’ve lived in Britain, I got exposed to afternoon tea. It’s an English tradition and I enjoy holding tea parties. Tea parties are where I invite people who have never met before, and pamper them with a range of teas paired with baked goods that I make myself. I really wasn’t a baker growing up, but in England apparently, my chocolate chip cookies, which are very soft, were the hit of the town because most English cookies, called biscuits over there, are very hard. Over the years I have expanded my baking repertoire to make things, typically finger-sized-bites, for afternoon tea. It’s only a recent hobby. Another thing is that I enjoy the outdoors. When we can get away, my husband and I like to go hiking and camping. I’ve been fortunate that I could either bicycle or walk to work all throughout my career. I also play flute in a church choir. That keeps my skills in music. Learning music was a wonderful thing that I’ve had all through my life, so I enjoy playing my flute.

That’s wonderful!

I’ve played lots of sports as well. And I got my, what’s known as the Cambridge Blue when I was playing basketball at the university there. It’s one of the high recognitions as an athlete. I played women’s basketball for many years and played in rec leagues and the like. But now, for fun today, it’s biking, hiking, and serving tea parties when we can get together again!

I’ll bet the tea party is going to be something that very few people knew about you. We like to come up with something like that because then people can understand you on a broader basis. So that was wonderful to hear.

I make little menus and show the different teas and where they come from, the pairings and all that. I laugh when I realize I never held “tea parties” as a child with my stuffed animals as companions. Now as an adult, I can embrace my inner childlike play, and enjoy real cake and conversation.

You mentioned your husband. Would you like to elaborate at all on your family life? Kids, pets, things like that? Or what your husband does?

My husband is an astronomer. He was also at Cambridge University. We met as students but didn’t get married until much later. He is project scientist for a robotic telescope in the Canary Islands. He has stayed in ground-based astronomy, and I like space-based astronomy (laughs), so our worlds don’t intersect. But what’s kind of fun is that his telescope, the Liverpool Telescope, has been in operation for over 15 years, as the first truly robotic ground-based telescope, designed as such from the outset, not just retrofitted. You operate it as if it was a space telescope. There are no observers. The telescope switches itself to use multiple instruments. It’s been interesting to compare their operations to the way NASA and other spacefaring nations or companies run their telescopes by remote operations. So, we share that robotic operations topic in common. Scientifically, he does time-domain astronomy capturing and monitoring when things go off in the universe. Hobbies-wise, he infuses the house with his photography, gardening, beer making, and all sorts of creations. So, at home, it’s just me and my husband, no pets, and ever so wide-ranging and imaginative dinner conversations.

You said that you walked to work, did I hear that right? So, do you live just across 101 somewhere close?

I live now in Boulder, Colorado, but when I was living in Mountain View, I lived about a 10-minute bicycle ride away, near Rengstorff and Middlefield. I enjoyed my bike rides back-and-forth from Ames. Occasionally I did walk to and from Ames, which took a bit more time. When I worked on New Horizons a few years back and was living in Boulder, I also cycled to my work place, more like 20-25 minutes away, and had to learn how to cycle in snow and ice, something you don’t get in Mountain View.

Can you think of an accomplishment that you’re very proud of that is not science-related?

I guess I could say my journal that is posted on the Queen Mary 2. I didn’t expect that to happen, that was a real surprise.

That’s true, and it’s amazing. We also ask who or what inspires you?

Besides my fellow colleagues that I work with, who come up with cool ideas and refreshing attitudes toward things? They would be the main source of inspiration for me. I’m also grateful that my parents allowed me to be a free spirit.

And do you have a favorite quote that you find meaningful or inspirational? If so, we’d like to include that.

I have a file where I keep a bunch of quotes I like. One that stands out is “Second star to the right and straight on ’til morning” originally penned by Scottish author James Matthew Barrie where Peter Pan describes to Wendy the way to Neverland. Apparently, the word “star” was added in by the Disney writers. Nonetheless, celestial connections or not, the quote evokes an image of being on fantastic voyage of discovery and adventure, tempered with some discipline, here, a direction, and a dash of hope, pushing one forward. Thank you for doing this series on our division members. I’ve been enjoying reading up about my colleagues and learning things that I wouldn’t normally know about them. We often talk shop when we get together, so now we have new conversation starters.

That is exactly the point, that was what Steve Howell had in mind when he suggested that we do these interviews, just to help get to know each other on a broader basis than just our interactions in the workplace. Thank you for taking a few minutes to chat with us. It’s been a delight.

Interview conducted by Fred and Sara on 8/19/21

Learn more about Kimberly Ennico-Smith’s work here.