We like to start out with your childhood, where you’re from, your family at that time, what your parents did, where you grew up and went to school, and if there was anything in those early years that captured your mind or got you thinking about science or specifically the space science that you have pursued, the planetary science, as a possible career field.

Well, I grew up in Westchester County which is a suburban county just north of New York City.

In Pelham, New York? I think I read that in your bio.

I was born in Mount Vernon and grew up in the town of Pelham. My dad’s father and uncle immigrated from Italy and built a big construction company. My dad and his brothers were all born here, became architects or engineers, and worked in the company, and I did too, as a laborer, during the summers while I was in high school and college. My mom’s family was from the West Indies, Jamaica. They were French and Irish/English, and they had also immigrated. Her father was a lawyer, she and her three sisters were all born here and they all went to college, which was unusual for women at that time. I was 12 at the time of Sputnik, and everybody said, “Oh well, you’ve got to be a scientist, you’ve got to be a rocket scientist!”. So it was in the air, it sounded exciting, so I thought “Well, I don’t know, it sounds like fun to me”, although I was interested in a lot of different things in school.

Did you have siblings?

Yes, I have a younger brother who lives in Santa Rosa and two younger sisters both of whom live back East, but we interact a lot. And I’m still close to several of my grade school friends and many of my high school friends, it was a small enough community.

In grade school and high school were you more or less self-interested in STEM type subjects or other types of things? You didn’t have to have a major then but did certain classes interest you more than others?

I think they all interested me. What I remember most about grade school were art and civil rights. We had current events, we would bring in news clippings from the local paper and they were about these courageous kids down in the South going through these picket lines and fighting for their rights. I remember thinking “Boy, they’re just a kid like me, and look at what they’re doing. Girls even.” I remember that to this day. In high school, my science teachers were kind of colorful and interesting, more so than my non-science teachers. I liked it but it wasn’t any driving passion. I decided to be an engineer because they said “Oh, you should be an engineer”, and engineers built cool stuff.

In high school, outside of studies, I got into a little of sports and photography. The summer before 9th grade, I worked on a construction job, and I made about $2.50 an hour – my friends were jealous! I was a pretty big kid and spent my time digging, taking nails out of boards, stacking and toting plywood around, and this and that, and I made enough money to buy a pretty nice Rolleiflex camera. I set up a darkroom in the attic of my parent’s house and became the high school photographer for a while. I took pictures for the class yearbook and for the town paper. I could wander around on the sidelines of all the football and basketball games freely and that was always fun. I took pictures of the high school celebrities, various candids, the seniors, and the juniors and all. It was a lot of fun and I’ve stayed with that hobby throughout my life. I worked construction maybe 8-9 years in the summers, running wheelbarrows full of concrete, lots of pick and shovel work, tarring roofs, helping the carpenters, whatever, learned a lot of construction trades, which have helped me over the years, letting me be the general contractor for our first house remodel, starting with digging the foundation, laying the rebar, poured the concrete, etc. A couple of Ames folks came out to help with the actual pour.

How did it come about that you went to Cornell? And how did you choose a major?

Well, I don’t really know. Cornell had a five-year engineering program at that time, and I liked the idea that you could take humanities electives because I didn’t just want to be a science nerd. The whole idea of MIT and places like that didn’t appeal to me. I was looking for something a little broader for a college experience. So the breadth appealed to me, and my dad had gone there, so I visited the campus. It was a gorgeous campus, and I thought “Wow, this is what college is supposed to be like”. A good friend of mine was also going there and I liked the whole package, so I applied for early admission. You didn’t have to pick an engineering major right away, so I took some EE classes, some Chem-E classes, and so on. Chemistry I didn’t like so much, especially organic, you had to remember all these names, but I liked physics because all you have to do is remember a couple of formulas and take it all from there. I decided to major in engineering physics, which covered a variety of different topics, materials science, EE, E&M, mechanics, thermodynamics, fluid dynamics, even some biophysics. The biophysics was primitive in those days and I remember thinking that it was really cool that you can study biology with physics, but what are you gonna do with it? It was just very handwavy, you know. I was on the crew team for a while but had to drop out as the coursework pilled up.

I was going to ask what you planned to do with it. How would you make a career with a major in, engineering physics?

At the time I assumed that with any kind of engineering degree, it just wouldn’t be a problem. I wasn’t that worried. Remember, in those days getting a job was just not a big deal for almost anybody with a college education. When I was done, I applied for a couple of jobs, and I got an offer at Raytheon in Boston. The work they described sounded kind of boring and I also realized when I got into the interview that I didn’t really know much of anything practical, things I thought I should have known, related to some of the interview questions they asked. I didn’t have much to contribute. So that’s why I decided to go on to graduate school and actually get good at something. Meanwhile, the war in Vietnam was going on, and graduate school allowed you to keep your student deferment. The graduate school I picked was in California – that was attractive as well in the summer of 1967 – so that was the next step.

Where was that? Which one?

Caltech. I had never heard of it. I had taken a couple of astrophysics classes as electives at Cornell and I liked them. I thought “This is really fun!” so I wanted to go to grad school in astrophysics. I got accepted to Princeton and also to Berkeley, I didn’t really want to go to New Jersey, not much of a change, and Berkeley didn’t offer me any money up front. I knew I needed to support myself, with my younger brother and sisters planning to go on to college, and Caltech did offer a full 4-year grad fellowship, so I went there. But the offer was not in the astronomy department; it was in planetary science, which was in the geology department. I thought “Well, I don’t know about this geology thing” so I asked the prof that I had taken the astrophysics class from at Cornell, Dewey Muhleman, “What is this Caltech place, is it any good?” That tells you how much I knew about anything. He said, “Oh yes, it’s one of the top places, and in fact, I am going there next year to teach”. He was going to be in the planetary science department doing radio astronomy of planets, so I thought that could be OK, he was a very good teacher. And that’s what I did – went to Caltech. I also thought I could live at the beach, didn’t look far on the map! Clueless there too.

OK, now describe the path from your graduate work that wound up with you coming to Ames. Was that somewhat immediate or was it kind of a zig-zag path?

I would call it a random walk. I did a thesis at Caltech on planetary radio astronomy with Dewey. I got to use and adapt the first code by Bob Leighton, a real gentleman, and Bruce Murray, a dynamic guy and later director of JPL, modeling the polar cap of Mars, and I observed Mars with Dewey, on the Caltech interferometer (2-3 radio telescopes hooked up together). It was my first excursion into numerical modeling with Fortran, punch cards, big stacks of computer bi-fold output. Dewey then suggested I concentrate on Mercury, it was under-studied (and difficult, moon-sized, and never far from the sun). The Mercury adaptation of the code was big for the time (it would probably run in about two seconds on my iPhone now) so I had to go into the Caltech computer center in the middle of the night to run it without anybody else on the system, with a big box of punch cards (laughs). I also worked with Andy Ingersoll on some fluid dynamics, he was also just starting as a prof, and got to know a lot of other heavy hitters, which of course is very important in your later career – Peter Goldreich, Gerry Wasserburg, Arden Albee, Gene Shoemaker, others. Caltech was interesting because it was THE place, you know, with all these famous people, I remember professors from other universities came in to give seminars and they would just beat up on them. It was kind of brutal and I didn’t know if I could survive in that kind of a world, frankly. I wasn’t any kind of standout grad student.

And you survived!

I did, but I kept my head down. They had to have a motivational talk with me. I later found out they called these “star chamber” sessions for wayward students. A couple of faculty were there telling me “Well, how come you’re not doing anything? We don’t care what you do but we want you to do something, get some results, and graduate.” By that time, I had gotten married, and we had our first son. I was having a fine old time, we had a lot of friends and enjoyed living in Sierra Madre canyon, hanging around the astronomy library and reading interesting stuff that had nothing to do with my thesis, and it never occurred to me that I was going to have to graduate and get serious! But they said, “Come on, you’ve got to wrap this up and move on or we’re gonna cut off your money in six months”! So, I wrapped it up and went off for my first postdoc, which turned out to be something of an inflection point.

So then did you get a postdoc at Ames, is that what got you here?

No, my first postdoc was at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst, with Bill Irvine, one of the few genuine radiative transfer experts, who at the time was also one of the world’s 2 or 3 experts on Saturn’s rings. He was going on sabbatical and wanted me to help his grad student with a Saturn’s rings problem. The grad student spoke relatively little English, so I had to learn a little bit about Saturn’s rings just to talk to him. Fortunately, there was only a little bit known about Saturn’s rings then. Meanwhile, I was going down to observe Mercury again with the big interferometer at the Green Bank Radio Observatory in West Virginia, which was much bigger than the Caltech interferometer. We observed Mercury all day but we had the telescope for 24 hours, so we just said, “What else can we look at?” Saturn was up all night and we wondered why no one had ever looked at Saturn and the rings with an interferometer so we looked at Saturn for a few nights. It turned out someone had, but they saw no rings at all, guessed it was because the rings were just tiny ice grains, and there were no papers on it. We got this really interesting data – we couldn’t see the rings either but the shape of the planet was strange. And right around that time JPL scientists bounced the first radar signals off Saturn’s rings and that was a huge puzzle. How can the particles reflect radar when they are too tiny to emit radio waves? This was a big thing in the community, and serious scientists were suggesting perfect metal spheres, or long metal needles, for example. Jim Pollack now entered the picture. Jim had this theory that it was a multiple scattering effects in rings made mostly of centimeter sized chunky ice particles. And Bill Irvine knew Jim. Jim was one of those famous guys like Carl Sagan, but at Caltech, they had thought Carl and Jim were a little “speculative” – not really solid. Well, Bill and I had a phone conversation with Jim, and I decided that his model was wrong and that I could prove it. We coded up another scattering model and applied it to my own radio data and it agreed! So I thought, “Well, maybe he’s right!” Around that time, we were thinking about coming back to California so I applied for what we now call an NPP Postdoc, working with Jim. But then, I thought I would just drop out of science because I found the academic environment too stuffy. So we dropped out for a while and went and stayed on a farm up in Canada, and then another one in Oregon. A couple of months later I got a letter in Oregon saying I had been accepted for the postdoc. So I walked down the road to the pay phone and called Jim and said “I’m not so sure I feel at home in science, do you think there’s any point in my doing this?” And he said, “You know, I think you’ve got potential”. So we moved down here, that was in 1974, and I loved this beautiful area, I loved Ames right away. It wasn’t the same stuffy environment as I had found in the universities, in academia. I liked the people: Ray Reynolds, Pat Cassen, Larry Caroff, Dave Black, just great people, and Jim. Jim was indeed brilliant, and fun to work with. I was his first postdoc even though he had been at Ames a year or two, that’s how far back that goes. I even worked in SETI for a while, with John Billingham and Jill Tarter, Ames was a big player in SETI at the beginning. Always lots of fun things to do at Ames.

Tell us a little bit about the work you’re currently doing and any high points along the way, things that you have learned or discovered, important research findings, things like that.

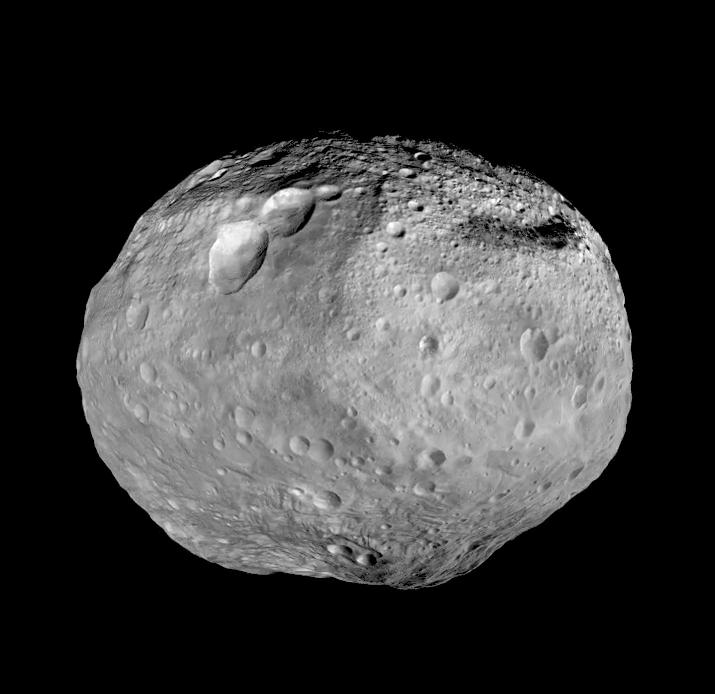

Over the years I followed the Saturn rings theme into rings of all the giant planets. Working with Jim I met Joe Burns, who (we figured out) had actually been my TA at Cornell, and he got me into dynamics of Saturn’s rings – we’ve worked together and been close friends for decades. I learned even more dynamics working with Frank Shu and his grad student at the time, Jack Lissauer. I got involved in Voyager originally because there just weren’t very many Saturn rings experts, and they invited me to join the imaging team to plan the Saturn ring observations. That was a real thrill for a young scientist, working alongside famous people like Carl Sagan, Gene Shoemaker, and others. I ended up leading the imaging team “rings group” through planning all the ring observations at Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. It turned out they all had rings. Who knew, right? I had a ring brightness model that we used to set the camera exposures in geometries no one had ever seen; I was worried they would all be over or underexposed but most of them were spectacular. Over the mission, working with the people I mentioned above and others, including Mark Showalter, Luke Dones, Dick Durisen, and Paul Estrada, I helped discover or predict spiral waves in the rings, moonlets in empty gaps, a new role for meteoroid bombardment that could limit the rings to a very young age, and some other things. So that was a huge high point in my career, seeing those beautiful ring systems up close for the first time. Working on Voyager led me to apply to be on Cassini, and I served as the interdisciplinary scientist for rings on Cassini, for Cassini’s whole wonderful 13-year mission, that made many other new discoveries and ended in September 2017. And that was also a great ride. I just happened to be in the right place at the right time with these missions going on.

Then in the mid-’80s, I picked up another thread of research which had to do with the formation of planetesimals from small particles in turbulence in the protoplanetary nebula. I reached out to people in the Ames fluid dynamics division, and Stanford, to make use of all their expertise in planetary problems and have benefitted a lot from that expertise to this day. I worked extensively with Bob Hogan, a brilliant young guy who never graduated from college, who died in 2012. With Bob, Tony Dobrovolskis, Thomas Hartlep and others, we’ve come up with one of two or maybe three plausible theories for planetesimal formation. It’s not the community favorite right now but it’s the only one that works if the nebula is turbulent; this is an unfinished story, as nebula turbulence is still highly uncertain. We’ve got several ongoing projects in the area of turbulence and particles led by Orkan Umurhan and our NPP Debanjan Sengupta; Paul is involved in this, too. One of the most challenging and fun aspects of this has been connecting nebula physics with the properties of primitive meteorites, a vast and puzzling record. They were there when it was all happening; you can hold in your hand something that formed in the nebula millions of years before the Earth did. I’ve been lucky to have a dozen or more NRC/NPP postdocs in these two general areas over the years, who have done and have yet to do more great work. So we have a strong cross-disciplinary group working on these problems, and I expect that work will go forward in the years to come.

Did you ever have anything to do with the Galileo project, with the probe or the orbiter?

No, not Galileo. When I first got here Ames had a lot of spacecraft planning and operation going on, and I did serve as the study scientist for the first Titan probe study though, back in the 70s and 80s – we briefed HQ and they liked our design so much they took it and gave it to JPL, which just destroyed our Project Division lead guy of course, and then it went to ESA as part of Cassini.

I ask because I was on that project for five or six years, I worked for Joel Sperans and Skip Nunamaker.

Yeah, I knew them both, there was a lot of collaboration between space science and space projects in those days when the centers led in studying new missions.

That was a good project. I was their financial manager and performance measurement analyst. If you weren’t a research scientist for NASA what would your dream job be?

Oh, I don’t know. If I were to start all over again I would maybe go into biology. I think biology is fascinating, an infinite source of mystery. Global warming is the big challenge facing the planet right now and I think I would like to spend more time with that, maybe after I retire.

We’re in kind of an unusual circumstance with this Covid-19 lockdown situation and everybody working remotely but in normal times what did you like best and least about your job?

The least part is easy, it’s all the bureaucracy. These things come down from on high, sometimes for no obvious reason, and you just deal with it. I was a branch chief for four years, and following Ray Reynolds, regarded the role of the branch chief as trying to keep some of this interference out of the hair of the scientists. So that’s sort of the downside. The upside of course, professionally, is it’s basically a hard money job and you can do risky, far-reaching research, constantly moving into new areas. But I always enjoyed interacting in person. I love going to seminars on all different topics, it’s a brain cleanser and I miss that quite a bit. Virtual is better than nothing, we have our group meetings now virtually pretty much every week, with small groups on the side. But running into people in the hall and chatting with people in the hall, I miss that.

As for the bureaucracy part, you’ll have to take a number and get in line because I think we’ve heard the same from practically everybody (laughs). What advice would you give to a young up-and-coming student who would like to have the kind of science researcher career with NASA that you’re having?

Well, be open to everything. Don’t stick with preconceptions. Listen carefully to everybody, even when they seem to be challenging you. It’s an opportunity to check what your own thinking is and get rid of any misperceptions you might have, which we all have. We all make mistakes. You can’t get too attached to your own biases and beliefs. Don’t be afraid to go in a new direction if you think there’s an interesting problem there. I started on Saturn’s rings and my advisor basically told me “That’s silly. What are you interested in that for? Stick with Mercury!” But I found Saturn’s rings fascinating, I became passionate about it, so follow things that you’re passionate about. Oh, and write shorter papers! (laughs). We used to be able to get away with these long blockbusters, but you can’t do it today. People don’t have the patience to read long papers. (laughs)

Is there anything about your life outside of NASA that you’d like to share? Home, family, kids, pets, trips, talents, hobbies, anything like that?

Well, yeah. I’ve been happily married for over 50 years now and we’ve got two boys who are both married, living up north of the Bay, and a little granddaughter now. We’re looking forward to getting together for the first time in a year this Sunday. Hobbies? I’m still interested in photography, and in genealogy. I’ve done some studies going back on both sides of my family, mostly from photos. I don’t get much from lines on charts. I’ve restored lots of beat-up photos from both sides of the family and done a little digging into the immigrant story, which is fascinating. I also enjoy gardening, especially my native plants and fruit trees. And I’m really interested in archaeology. I had a chance to go to Catalhoyuk, a 9000-year-old settlement in Turkey, in 2016 which was the experience of a lifetime. Orkan’s wife was co-leading the dig and helped me get in there for a few days, and that was just great fun. I’ve been to many of the old Painted Caves of France and burial tombs in the UK, just fascinating, the emergence of early humans from near-animal nature to dreaming and planning large symbolic projects. It’s just a fascinating part of evolution.

Are you musically inclined? Do you play an instrument or anything like that?

I fooled around with a harmonica for a few years, but I haven’t played it for quite a while now.

OK, I’ll expand on that, then. What do you do for fun?

This past year, I have to say, my work-life balance has gotten a little out of kilter but what I do for fun, what I like to do, is just spend time with family and friends, play in the yard, tend to my plants and trees. I love to go on hikes and used to camp a lot. We’ve done a lot of travel over the years, US, Europe, Peru, and there are still some places I’d like to go see but the idea of travel right now is iffy. Oh, and my photoshop, my cameras, and some political action now and then.

What accomplishment are you most proud of that is not science related?

I’m proud of serving as branch chief of SST for four years. It was a very difficult time for the branch. Dan Golden was the administrator at the time and he was determined to shake up the agency, maybe you remember, Fred. He came in here and ripped into Dale Compton and a lot of the traditionalists, and was tearing the place apart. He wanted to take Ames Space Science out of NASA, make it an institute. There were a lot of challenges going on in those four years. But we had a management team that worked well together, and I think we came out of it strong with astrobiology, astrochemistry, Mars atmosphere, and general origins research, and I’m proud of my small contribution to that saga.

Yes, I remember. Those were indeed some dark days and I appreciate what you and others did to preserve Ames and improve it. We also ask, “Who or what inspires you?”

Today?

Sure. Anytime, throughout your life. Has there been anything or anyone that you have looked up to as being inspirational or motivational?

Well, I have a lot of respect for my grandfather for starting with nothing and establishing quite a nice business, an interesting, practical, useful business. And those little black schoolgirls in the 50s and 60s, I remember very well being inspired by them, and I still am, going through picket lines with a lot of screaming people. That cause is still with us, unfortunately.

Do you have a favorite space image or an image of your work or your life? Something that you find particularly pleasing enjoyable, motivational or just beautiful?

And we also ask if you have a favorite quote?

No, not right now, except the quote I have as a tag line in my email that says: “You can’t believe everything you read on the Internet”, attributed to Abraham Lincoln! (laughs)

I like that, that’s very good!

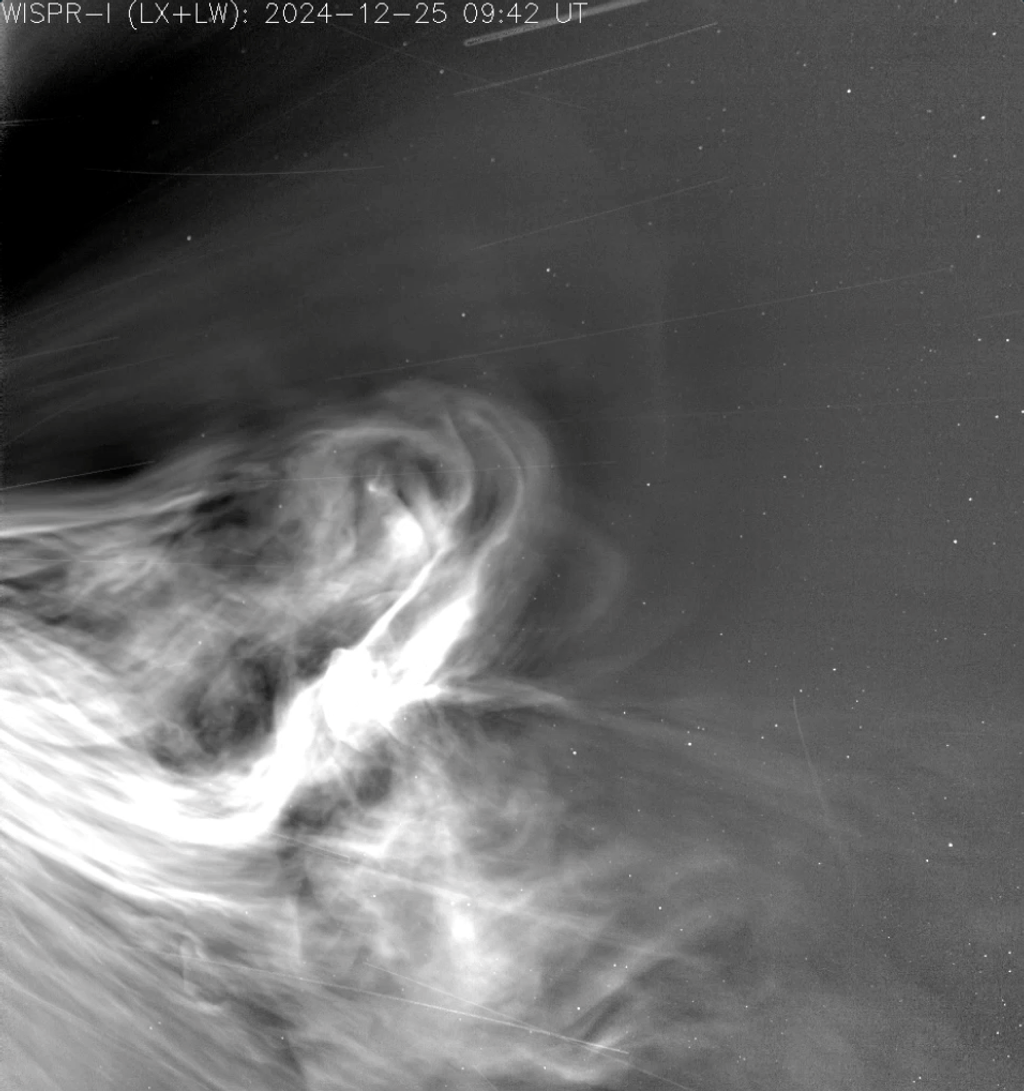

As far as pictures, the one I have had on my wall for years was the Voyager 1 “Goodbye Saturn” picture, looking at Saturn on the way outwards because Voyager was such a thrill. It was a geometry that humans had never seen before. It’s just a beautiful picture, simple, just one frame, no color, very ethereal, the shadow of the planet right on the rings, ringshine on the dark face of the planet. I have had that on my wall for more than 30 years.

By the way, you were talking about genealogy. Did you do any of those tests, the DNA tests, to see where you came from? And what your family history was?

Oh, yes, I did “23andMe” and it was no real surprise. I mean we kind of knew the general story there. The only surprise was it looks like I’ve got some few percent of Spanish or Iberian ancestry, and that comes from a Spanish great-great-great-grandfather on my mother’s side, who came to the New World and settled in Columbia, where he ran an emerald mine. This was when Columbia was part of the Viceroyalty of New Granada. He married a girl who I think might have been partly native American, I’m not sure. Anyway, that’s my Spanish-Iberian connection.

That’s amazing. I love that.

I think I’ve also got some Balkan, maybe Albanian. It’s right across the Adriatic Sea from Italy, and my family is from the south of Italy so there was a lot of going back-and-forth.

Yeah, I’ve checked my family history on both sides and I have some Dutch, of course – actually they call it Western European, and a chunk of English, but what I found out from Ancestry DNA is I’ve also got Irish and Scandinavian. So I’m a mongrel!

It’s in your eyes, Fred, I can see it! (laughs)

Jeff, it’s just been wonderful talking to you we really appreciate your setting aside a half-hour for us to chat with you and we’ll get this going, get it on paper and ready to post, hopefully in the not-too-distant future.

Thanks for thinking of me and I hope some of this is of interest to somebody.

Definitely. Thank you very much.

Interview conducted by Fred and Sara on May 4, 2021, and edited July 27, 2021

To learn more about Jeff Cuzzi’s work visit his profile.