4. . . 3. . . 2. . . 1. . . liftoff!

All of a sudden a tiny NASA-funded satellite, one of many passengers aboard the SpaceX Dragon spacecraft, shot into the sky on a mission to prove its new technology could change the way we measure Earth, and eventually, the Moon.

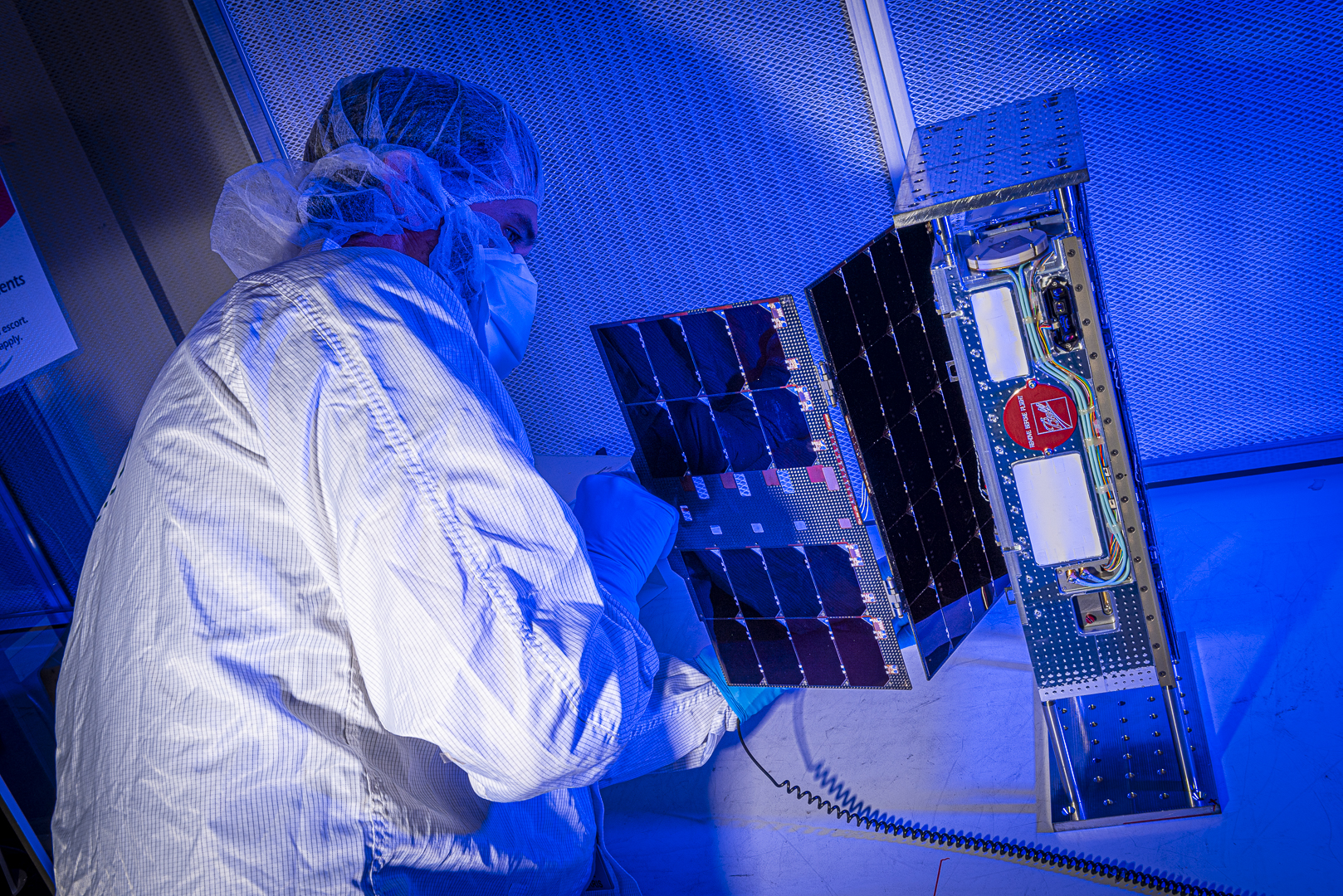

The Compact Infrared Radiometer in Space instrument on a CubeSat, also known as CIRiS, launched from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida to the International Space Station on Dec. 5. The backpack-sized satellite is aiming to collect, process and calibrate infrared images to reveal Earth’s temperature for the first time from a small satellite. “If we can do this, we have greatly increased the value of the data for Earth Science applications, as well as land and water management,” David Osterman, the CIRiS Principal Investigator at Ball Aerospace, said.

Farmers could use CIRiS’s data as they determine if a grove of orange trees needs more water or if a vineyard is too wet. In fact, farmers, water managers and other decision makers are beginning to use remotely sensed estimates of consumptive water use from larger sensors like the Thermal Infrared Sensor (TIRS) aboard Landsat 8, which is jointly run by the U.S. Geological Survey and NASA.

CIRiS aims to demonstrate new capabilities to complement future NASA Earth-observing missions like Landsat, increasing the frequency of image collection at a potentially reduced size and cost. “We’re looking to achieve high performance in everything while still fitting into a small space,” Osterman said.

Even before CIRiS left Earth, NASA funded its sibling, L-CIRiS, which has an “L” for lunar, to head to the Moon and use similar instruments to identify lunar minerals. L-CIRiS will also be built by Ball Aerospace and was selected as part of NASA’s Artemis lunar program, which will help NASA send astronauts to the Moon by 2024 as a way to prepare to send the first humans to Mars.

The Earth-observing CIRiS is currently on the space station. It will stay there for a few weeks until it’s transferred to the Cygnus cargo vehicle, which will take it 100 kilometers higher than the space station for deployment.

Small satellite, big data

Small satellites, including CubeSats, are playing a growing role in exploration, technology demonstration, scientific research and educational investigations at NASA. Missions to date have included planetary space exploration, Earth observations, and fundamental Earth and space science. CubeSats are also used to develop precursor space technologies like cutting-edge laser communications, satellite-to-satellite communications and autonomous movement capabilities.

The CIRiS CubeSat, which can remotely measure the Earth’s surface temperature, miniaturizes a number of components and eliminates others that conventional instruments use to collect longwave (infrared spectrum) images. These images indicate hot and cold regions as colors on a “heat map” display.

Once CIRiS collects these images, it calibrates them while in orbit, which means it assigns validated numerical values to each pixel. “Calibration allows you to take data and move them a step further to where they have scientific significance and can contribute to actual science,” Osterman said. Not only can you see if a stretch of land is warmer than its surroundings, you can see by how much.

For instance, infrared measurements can help scientists better understand evapotranspiration, which is the water evaporated from soil plus the water released from plant leaves as they transpire, or breathe. Evapotranspiration helps to cool the plants, so temperature is a key indicator of plants’ water use. Knowing the quantitative level of evapotranspiration is useful to crop growers as they determine which plants need more water.

The objective of the CIRiS mission is to validate and demonstrate new technology. If successful, a potential next step would be a mission that adds the capability to collect images in the visible part of the spectrum to determine plants’ colors and leaf area. Visible light can reveal how much sun plants are receiving and how healthy they are.

Applying the data

Collecting images in both the visible and infrared bands will help the viticulture industry, for example. Grapes used for wine need specific conditions to flourish. “Growers typically want to be able to impose stress on the grapevines during certain development stages to control vegetation growth, which determines how much sugar develops in the grapes, among other qualities,” Bill Kustas, a scientist with the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service in Beltsville, Maryland, said.

Bill Kustas and colleague Martha Anderson are leading a NASA-funded project called GRAPEX, in collaboration with winery E&J Gallo, aimed at integrating thermal remote sensing information into irrigation decision-making tools for vineyards. “It’s a huge challenge to irrigate wine grapes to get to the targets growers want to achieve,” Anderson said.

On a broader scale, crop growers throughout California need to be able to report their water use to comply with the State of California’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA), which aims to help the state more efficiently use and conserve groundwater reservoirs that supply it with freshwater. “Growers see remotely sensed evapotranspiration information as valuable for conforming to SGMA because they can use the remote sensing to estimate how much water they’re using rather than trying to dig this information out of their irrigation records,” Anderson said.

Testing the technology

CIRiS collects infrared energy and uses a “focal plane” to convert that energy to an electrical signal, similar to how a digital camera turns visible light energy into an electrical signal. Many focal planes for infrared detection require operation at cryogenic temperatures, and therefore must incorporate a cryocooler to establish those temperatures, Osterman said. The team decided to use a different type of focal plane that operates without cryocooling to decrease the sensor’s size.

Although CIRiS’s focal plane doesn’t have the same level of sensitivity as a larger focal plane with a cryocooler, it hopes to make up for any deficiencies with robust abilities to process the data. “We’re trying to substitute software performance for hardware performance,” Osterman said. The software aspect, or data processing, is initiated on the spacecraft and then continues after the data are downlinked to the ground.

Data collected by CIRiS can be compared with images from other NASA thermal sensors currently in space, such as the ECOsystem Spaceborne Thermal Radiometer Experiment on Space Station (ECOSTRESS). Collectively, NASA research instruments like CIRiS and ECOSTRESS help to identify optimal sensor characteristics that can be transitioned into long-term monitoring programs, Anderson said.

If the CubeSat is successful in proving it can operate in space, Osterman hopes to see a small constellation of CIRiS-like instruments orbiting Earth. Multiple CubeSats in orbit would allow us to measure changes in evapotranspiration and other phenomena potentially as often as every day.

“It’s been really exciting to see how small instruments and spacecraft can contribute to our understanding of Earth and eventually the Moon,” Osterman said.

By: Elizabeth Goldbaum

Earth Science Technology Office