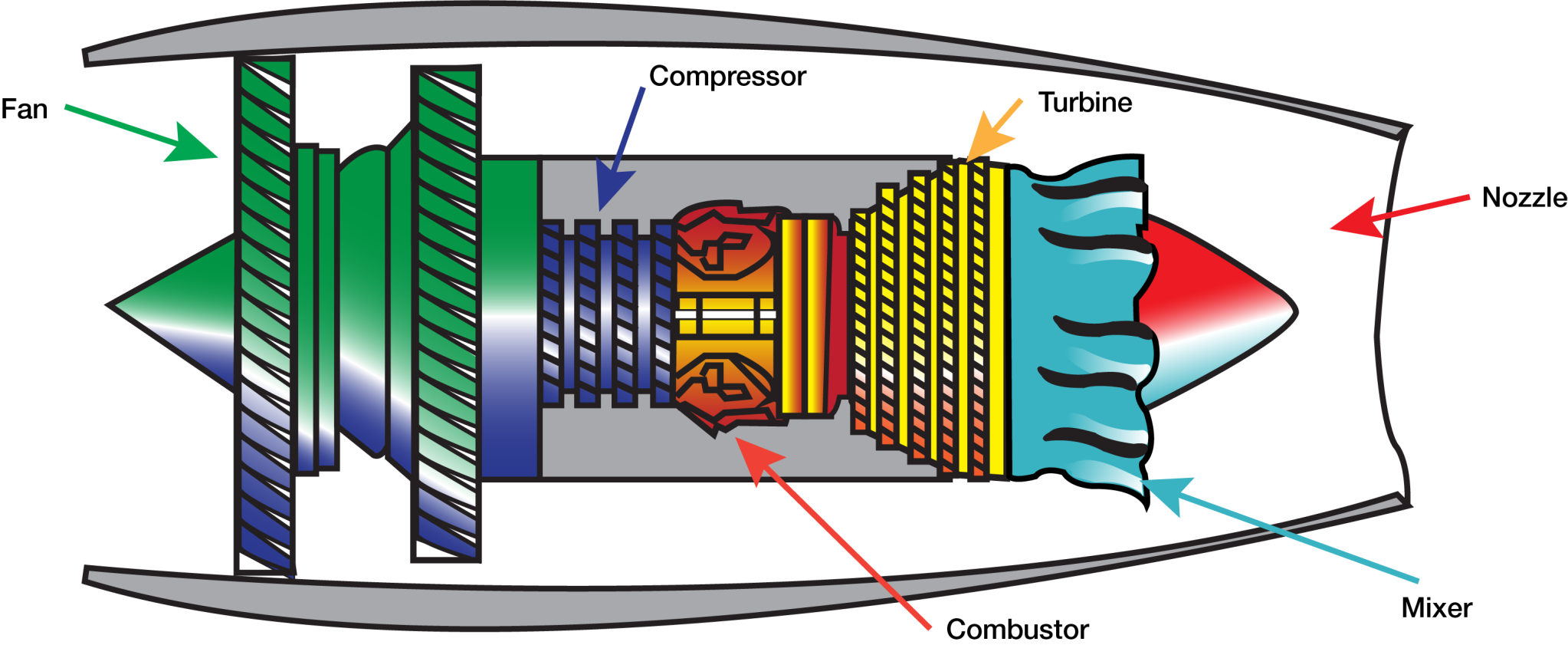

Jet engines have remained relatively the same for 60 years: pull air in, squeeze it, heat it, exhaust it. The final three steps – compress, combust and exhaust – make up what’s called the engine’s core or its powerhouse. Today’s engines are finely tuned machines, but there’s more that can be done to make them more efficient.

With NASA’s focus on highly efficient hybrid-electric aircraft, engineers need to shift how aircraft engines have traditionally been designed, especially in terms of core size.

By shrinking the core, it increases what’s known as the bypass ratio of the engine, meaning the fuel burn rate is only slightly changed by the addition of the larger inlet fan. Therefore, the engine generates more thrust for roughly the same fuel burn, making it more efficient.

“Greater fuel efficiency is the ultimate goal, which will eventually lead to lower costs and emissions,” said Tony Nerone, Hybrid Thermally Efficient Core (HyTEC) project manager at NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland. “But we must be able to significantly reduce the size of the engine core to improve fuel burn without impacting operability, durability, and performance.”

For the HyTEC team, the question is: how small? How small, or compact, can the core and its various components be while still improving efficiency? And the smaller parts become, the more challenging it becomes to improve performance while maintaining durability of the parts.

“As we make the internal blades, not the outside blades for intake but those inside the compressor and turbine sections, smaller – about the height of a dime – we also have to address gaps between the blades and the engine housing to maintain performance,” said Nerone. “It is a challenge to minimize performance losses, and it is further complicated as sizes reduce, but the fuel burn reduction predictions are worth the effort.”

NASA and its industry partners have already conducted initial testing on concept small core compressor and combustor sections at NASA Glenn. Those tests produced positive results and NASA is now moving forward with HyTEC to further investigate small core development and address related challenges.

For example, if everything is smaller, in order to maintain power to drive the fan and compressors, temperatures will increase especially in the already hot areas of the engine.

“Temperatures may rise 200 degrees Fahrenheit or more; that’s a sizeable increase,” said Nerone. “We need new materials capable of handling the heat.”

NASA is developing promising high-temperature materials called Ceramic Matrix Composites and working on innovative ways to cool things down.

The agency will soon seek proposals from industry to help improve the engine thermal efficiency and decrease fuel burn.

The goal is to get a small-core engine for subsonic commercial aircraft to market within 10-12 years. That means in order to fly by the mid-2030s, there is an urgent need to develop these highly efficient engine technologies now.

Credits: NASA

Cleaner Flights

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, reports showed air travel was growing exponentially, particularly in Asia. So, assuming that trend eventually resumes, and more planes are in the air, the threat of increased pollution is another area NASA is concerned about. Less fuel means fewer emissions, which is why this small core effort is so important.

“If we put more planes in the air and keep the environmental impact flat, without an increase from today’s levels, that would be a win,” said Nerone. “If NASA can prevent additional or even reduce aviation environmental impacts, that would be a great accomplishment. This will also give the American aircraft industry a competitive advantage in this market.”

More Power Equals Increased Comfort, Performance

Passengers and planes, too, will benefit from the small-core engine’s improved efficiency. As engines become more electrified, the core will still provide more power to the plane’s various subsystems, like cabin temperature control and hydraulics, and manufacturers may even replace some hydraulic systems with electric components.

This can be accomplished through power extraction, where planes siphon power from the core to operate other systems. At present, the Boeing 787 Dreamliner has the highest electric power usage at around 5 percent. HyTEC’s new power extraction technologies could significantly increase the electric power available.

“We’re looking to increase to 10%-20%, or two to four times greater than the current state of the art,” said Nerone.

This increase in power extraction could also enable future hybrid-electric aircraft – like NASA’s STARC-ABL concept – where the power pulled from the turbine engines would be used to drive all-electric fans that would contribute to inflight propulsion.

With the goals of increasing efficiency, generating more power, reducing size and emissions, and improving durability, NASA’s HyTEC project could result in cheaper flights, happier fliers, and cleaner air.

Mike Gianonne

NASA Glenn Research Center