In early 1966, Gemini VIII chalked up another crucial spaceflight technology milestone for the United States. But the triumph quickly became an in-flight emergency, testing NASA’s quick-thinking skills to bring the astronauts safely home.

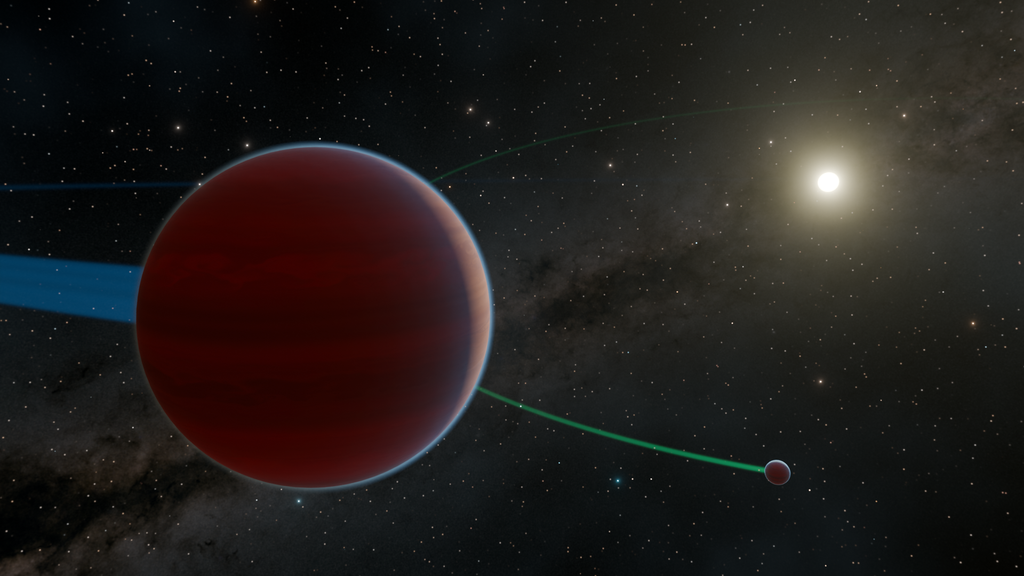

The crew of Gemini VIII was the first to link two spacecraft together in Earth orbit. This milestone would prove vital to the success of future moon landing missions. Catching up with already-orbiting spacecraft also has been essential during missions to the International Space Station.

Command pilot Neil Armstrong and pilot David Scott flew the most ambitious space mission to date. On the fourth revolution of the three-day flight, they were to rendezvous and perform the first docking with the separately launched Agena. Scott also was scheduled to perform a spacewalk of more than two hours to retrieve an experiment from the front of the Gemini’s spacecraft adapter and activate a micrometeoroid experiment on the Agena. For further tests, Scott then would return to the Gemini and don an Extravehicular Support Pack stored at the back of the spacecraft adapter.

A former Naval aviator, Armstrong was a member of the second group of NASA astronauts. As a test pilot, he flew the X-15 rocket plane at Edwards Air Force Base, California. He went on to command Apollo 11 in 1969, during which he became the first person to walk on the moon.

A U.S. Air Force pilot, Scott was the first member of the third group of astronauts to fly in space. He later was command module pilot on the Apollo 9 flight in 1969 and commander of the Apollo 15 lunar landing mission in 1971.

Gemini VIII’s dual launchings took place on March 16, 1966. Coincidentally, it was the 40th anniversary of Dr. Robert Goddard’s demonstration of the world’s first liquid-propellant rocket.

Kennedy Space Center’s then Deputy Director for Launch Operations, Merritt Preston, called the Gemini VIII mission one of the most complex countdowns ever conducted. He explained that there were multiple counts running concurrently involving both the Atlas Agena and Gemini Titan rockets and spacecraft. Additionally, operations were coordinated between Cape Kennedy (now Cape Canaveral) Air Force Station, the Eastern Test Range, Mission Control in Houston and the ground tracking network around the world.

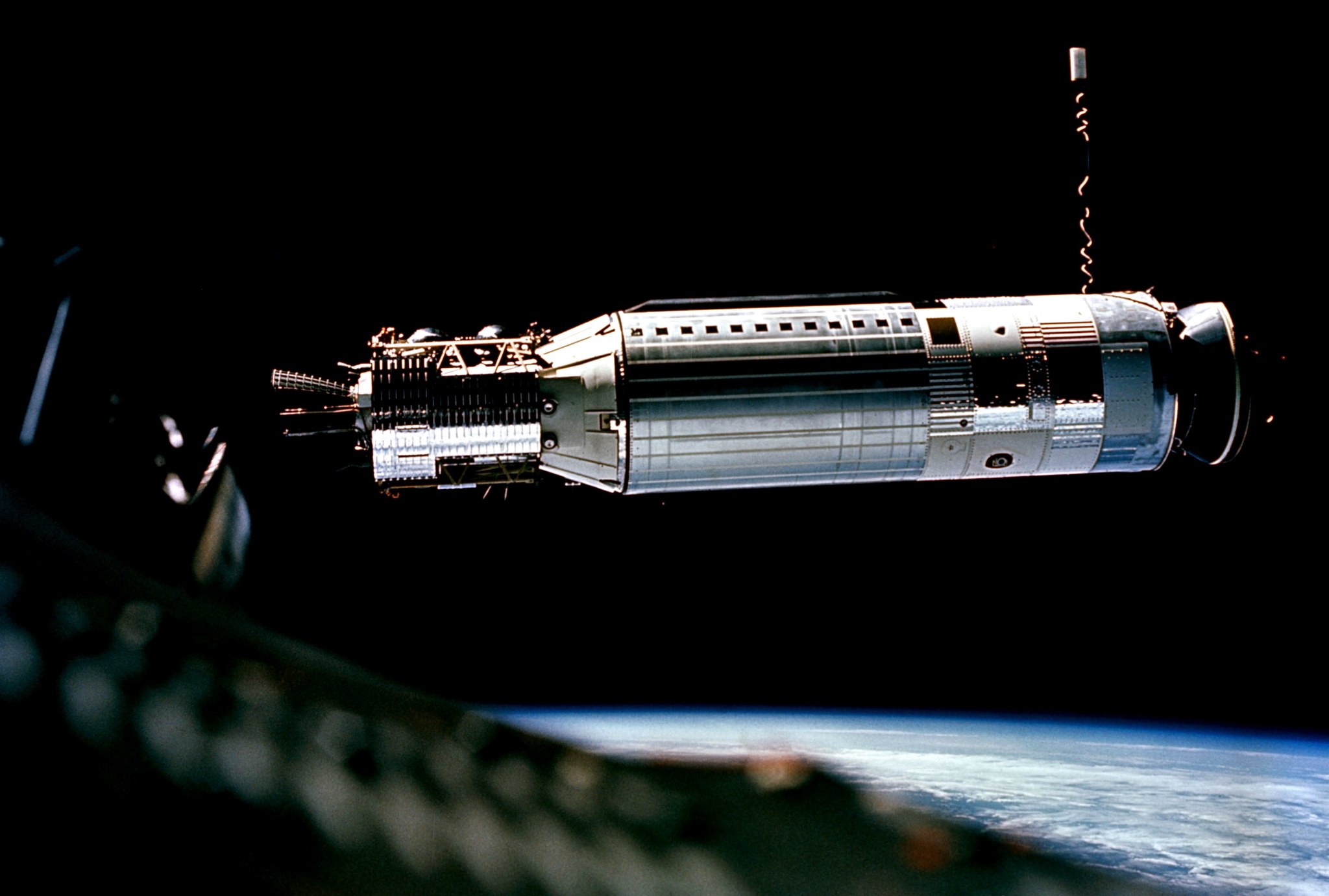

The Agena lifted off at 10 a.m. EST from Launch Pad 14 at the Cape atop an Atlas rocket. An hour and 41 minutes later, Gemini VIII was boosted by a Titan II from Pad 19 just north of the Atlas launch complex.

The successful countdown brought high praise from Kennedy Director Kurt Debus.

“What the nation could not see was the matchless coordination and competence demonstrated by two launch teams counting down simultaneously these sophisticated vehicles and spacecraft,” he said.

Gemini VIII’s orbital chase was on.

Three hours, 48 minutes into the mission, Armstrong and Scott trailed the Agena by 179 miles. Back in Mission Control Houston, spacecraft communicator Jim Lovell asked the crew for an update.

“Do you have solid radar lock with the Agena?” said Lovell, who flew on Gemini VII three months earlier.

“That’s affirmative, we have solid radar lock,” said Armstrong, while passing over the Tananarive (now Antananarivo), Madagascar, tracking station.

This was good news as it confirmed the Gemini spacecraft rendezvous radar instruments were tracking the Agena as planned.

As Armstrong and Scott closed in, they spotted the silver target rocket in the distance.

“OK we’ve got a visual on the Agena at 76 miles,” said Armstrong.

Since he could see the Agena, Armstrong judged his braking action by eye as Scott called out radar range and the closing rates. Soon the second rendezvous in the Gemini program had been achieved.

“Houston, this is Gemini VIII we’re station-keeping with the Agena at 150 feet,” Scott said.

The 35-minute fly-around allowed the astronauts to take a close-up look at the Agena and determine that it was safe to link up with the orbiting spacecraft.

Off the coast of South America, Keith Kundel was the spacecraft communicator onboard the USNS Rose Knott Victor tracking ship passing along direction from Mission Control.

“OK, Gemini VIII we have TM (telemetry) solid,” he said. “You’re looking good on the ground. Go ahead and dock.”

“Flight, we are docked,” Armstrong radioed back. “It was a real smoothie.”

Things had gone well up to that point. Shortly after docking, Lovell had a message from Mission Control Houston just before the spacecraft passed out of communications range.

“If you run into trouble, and the attitude control system of the Agena goes wild, just send in command 400 to turn it off and take control of the spacecraft,” he said.

The Agena was designed to obey orders from both the Gemini spacecraft and ground control. The Agena soon started a command program stored in its internal system. This instructed the Agena to turn the two spacecraft, but Scott noticed they were moving the wrong direction.

“Neil, we’re in a bank,” he said.

Armstrong used the Gemini’s orbital attitude and maneuvering system, or OAMS, thrusters to stop the tumbling. However, the roll immediately began again, and Gemini VIII was out of range of ground communications.

As Armstrong worked to regain control of the spacecraft, he noticed that the OAMS propellant was below 30 percent, an indicator that a Gemini spacecraft thruster might be the problem. Scott cycled the Agena switches off and on. Nothing helped.

Although it was not confirmed until later, a yaw OAMS thruster was firing erratically, later believed to be due to a short circuit in the wiring.

Not knowing, the crew’s first reaction was to blame the Agena. So Scott pushed the undock button, and Armstrong backed Gemini away from the Agena.

Without the added mass of the Agena, the Gemini’s rate of spin began to quickly accelerate. Soon after, Gemini VIII came in range of the tracking ship USNS Coastal Sentry Quebec, stationed southwest of Japan.

“We have serious problems here,” Scott said. “We’re tumbling end over end. We’re disengaged from the Agena.”

A surprised James Fucci, spacecraft communicator aboard the ship, asked what the problem was.

“We’re rolling up and we can’t turn anything off,” Armstrong said.

As the spin rate approached one revolution per second, the astronauts’ vision became blurred. The tumbling needed to be stopped.

Armstrong’s quick thinking led him to turn off the entire OAMS system and then use the re-entry control system, or RCS, thrusters on the nose of the spacecraft to regain command of Gemini VIII and stop the spin.

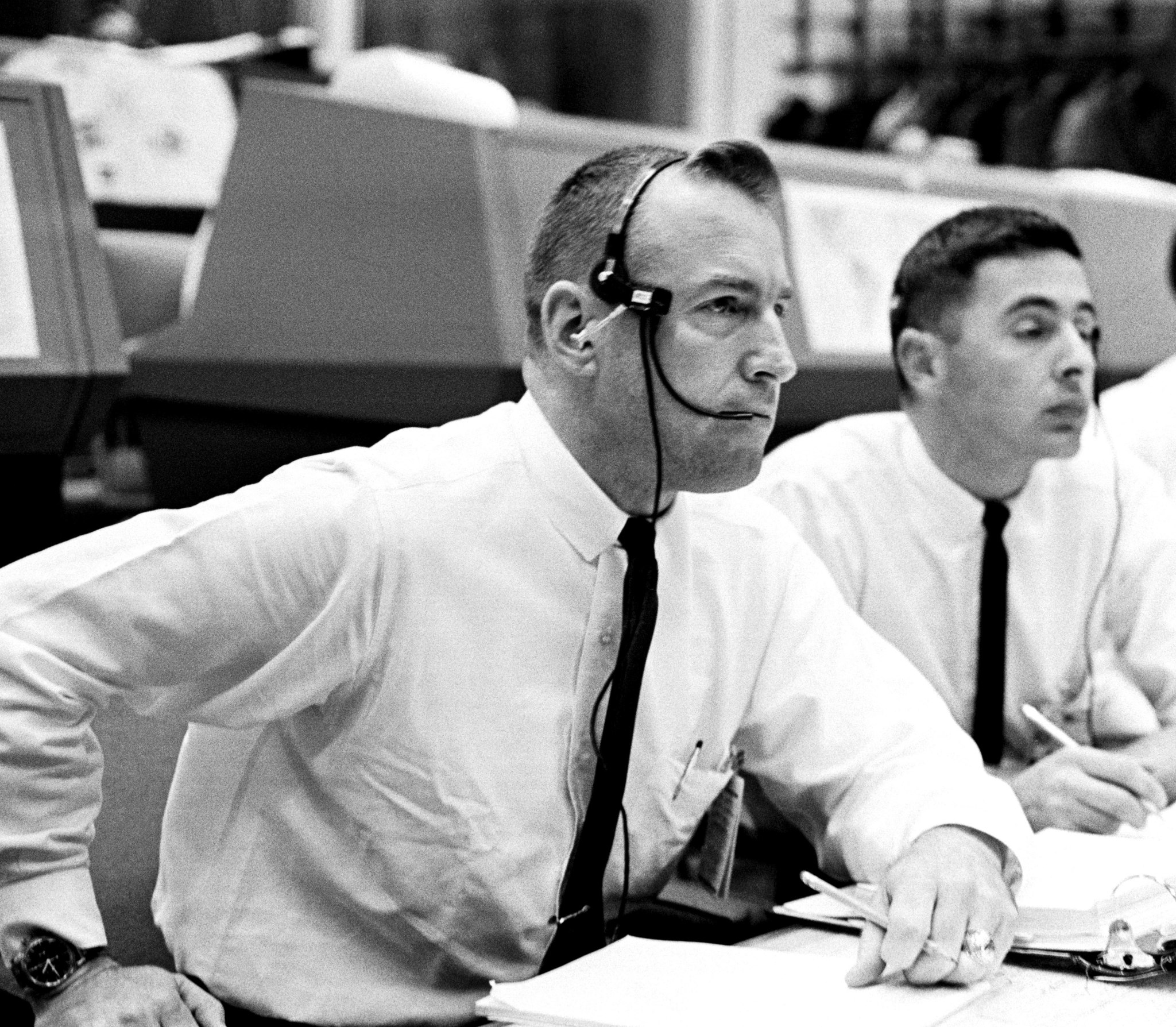

In the meantime, John Hodge was in his first mission as chief flight director in the control center in Houston. He had to make some quick decisions too.

While problems had come up on earlier U.S. spaceflights, crews and ground controllers found a way to complete the missions. In this case, Hodge knew Armstrong used almost 75 percent of the re-entry maneuvering propellant to stop the spin. The decision was made to follow the mission rules that dictated once the RCS was activated, the crew must be brought home.

Hodge decided to have Gemini VIII re-enter after one more orbit and land within range of the secondary recovery forces. The U.S. Navy destroyer USS Leonard Mason was requested to head toward the new landing site 620 miles south of Yokosuka, Japan.

Splashdown occurred within two miles of the predicted impact point 10 hours, 41 minutes after liftoff. To support the recovery, several aircraft raced to the landing zone from Naha Air Base, Okinawa, and Tachikawa Air Base, Japan. Once the Gemini VIII spacecraft was spotted in the water, three U.S. Air Force pararescuers jumped from an aircraft into the sea to attach a flotation collar to the capsule and assist Armstrong and Scott while waiting for pickup by the crew of the Mason.

Back in Mission Control, the flight control team performed maneuvers with the Agena to see how it reacted to commands from the ground. Since things went well, the Agena was left in orbit and served as a passive rendezvous target for the Gemini X mission later that year.

In the post-flight investigation, no conclusive reason for thruster malfunction was found. However, for future missions, a master switch was added to the Gemini spacecraft to make it possible for astronauts to turn off individual elements of a system not working properly.

Following the flight, Debus congratulated those supporting the mission and NASA’s skilled handling of the in-flight emergency.

“The successful launch of the Atlas Agena target vehicle and Gemini VIII within a period of 101 minutes was a superb performance leading up to the first successful rendezvous and docking maneuver,” he said. “Our pride in this achievement was tempered, however, by the deep concern for the crew during the later hours of an historic day. That astronauts Armstrong and Scott achieved a completely successful re-entry gives the nation cause for rejoicing in their heroism and skill.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the fifth in a series of feature articles marking the 50th anniversary of Project Gemini. The program was designed as a steppingstone toward landing on the moon. The investment also provided technology now used in NASA’s work aboard the International Space Station and planning for the Journey to Mars. In June, read about an orbital rendezvous with an “angry alligator.” For more, see “On the Shoulders of Titans: A History of Project Gemini.”