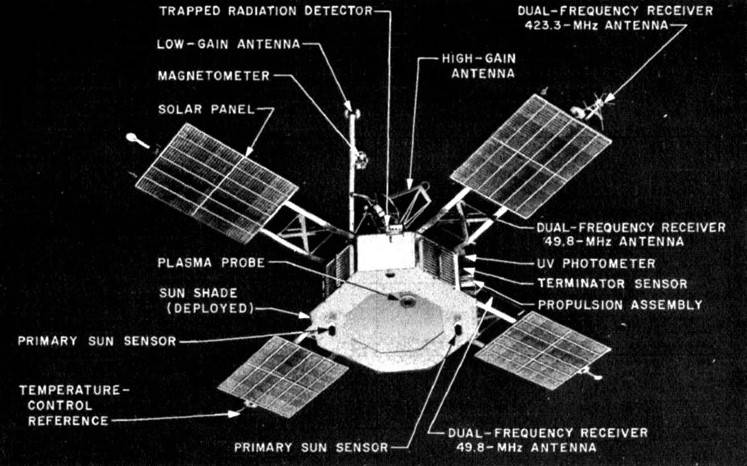

In 1967, as NASA continued preparations for the first human landing on the Moon, the agency once again turned its attention toward exploring Venus. Engineers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, modified the backup Mariner 4 spacecraft to operate closer to the Sun, and on June 14, 1967, NASA launched Mariner 5 on a 127-day journey to the mysterious cloud-shrouded planet. The spacecraft flew by Venus on Oct. 19, 1967, returning valuable information about the planet’s atmosphere and its radiation and magnetic field environment. The Soviet Union launched their Venera 4 spacecraft during the same launch window, its capsule descending into the planet’s atmosphere before falling silent. Scientists from both countries jointly published the results from the two spacecraft.

Left: Liftoff of Mariner 5 from Cape Kennedy Air Force Station, now Cape Canaveral

Space Force Station in Florida. Right: Image of the Mariner 5 spacecraft.

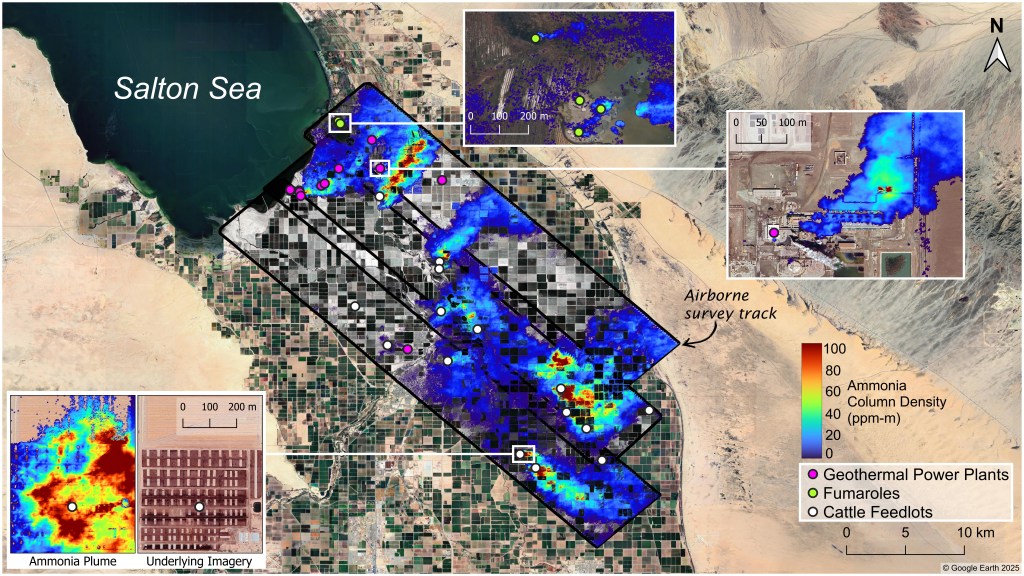

Following its launch on June 14, 1967, the 540-pound Mariner 5 entered solar orbit on its way to Venus. A course correction maneuver on June 19 refined this trajectory. During September and October, the spacecraft conducted joint observations of interplanetary space with Mariner 4, still operating in solar orbit after its Mars flyby. On Oct. 19, Mariner 5 flew within 6,309 miles from the center of Venus, about 10 times closer than its predecessor, Mariner 2, did in December 1962. Mariner 5 conducted seven investigations to study the planet as well as interplanetary space before and after the encounter:

- The solar plasma probe to monitor the properties of the solar wind.

- The helium magnetometer to measure the direction and strength of the magnetic field.

- The trapped-radiation detector to measure the flux of energetic particles.

- The ultraviolet photometer to detect atomic hydrogen and oxygen in Venus’ upper atmosphere.

- The celestial mechanics investigation to help refine the orbits of Earth and Venus.

- The S-band radio occultation experiment to measure the density of Venus’ atmosphere as the spacecraft passed behind the planet.

- The dual-frequency propagation experiment to provide information on Venus’ ionosphere.

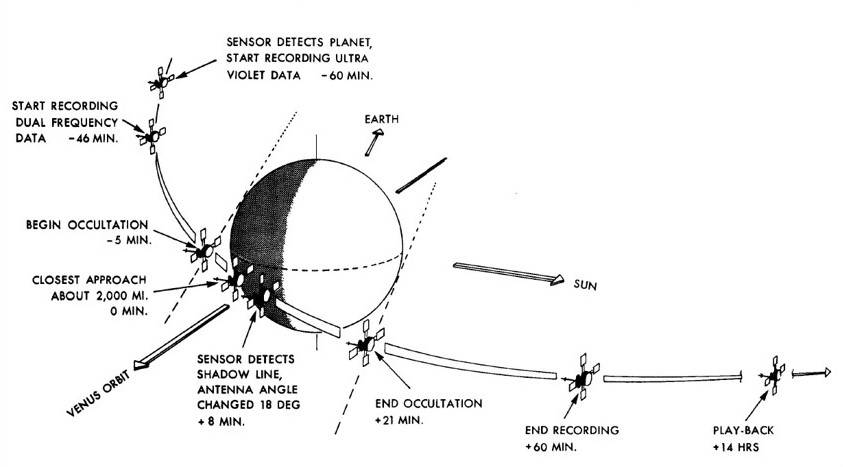

Left: Image of Mariner 5 showing its major components and scientific instruments.

Right: Schematic of Mariner 5’s trajectory during its flyby of Venus.

As Mariner 5 flew behind Venus, its radio signal passed through the planet’s atmosphere, providing detailed information about atmospheric pressure (75-100 atmospheres) and temperature (527oC). The spacecraft found no trapped radiation belts around Venus as its magnetic field was only 1% as strong as Earth’s. So despite Venus’ similarity to Earth in terms of size, the spacecraft found a much different world, dispelling visions of Venus as a planet potentially hospitable to life. Ground controllers lost contact with Mariner 5 on Dec. 4, 1967, briefly regained contact on Oct. 14, 1968, before giving up further attempts to communicate with the spacecraft on Nov. 5.

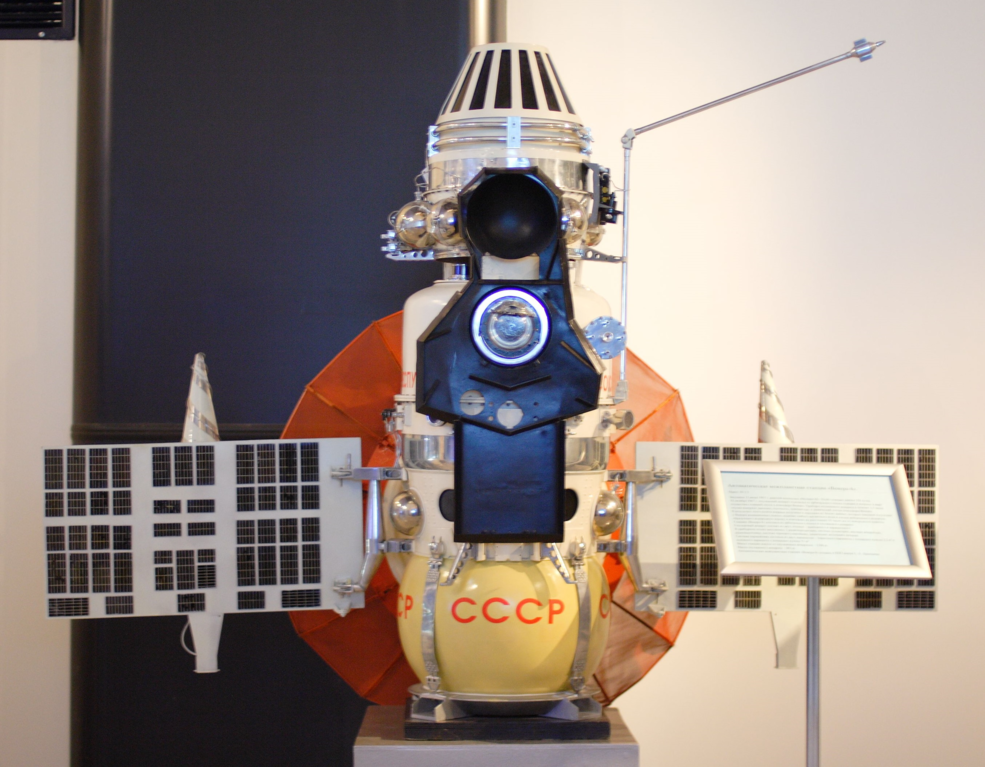

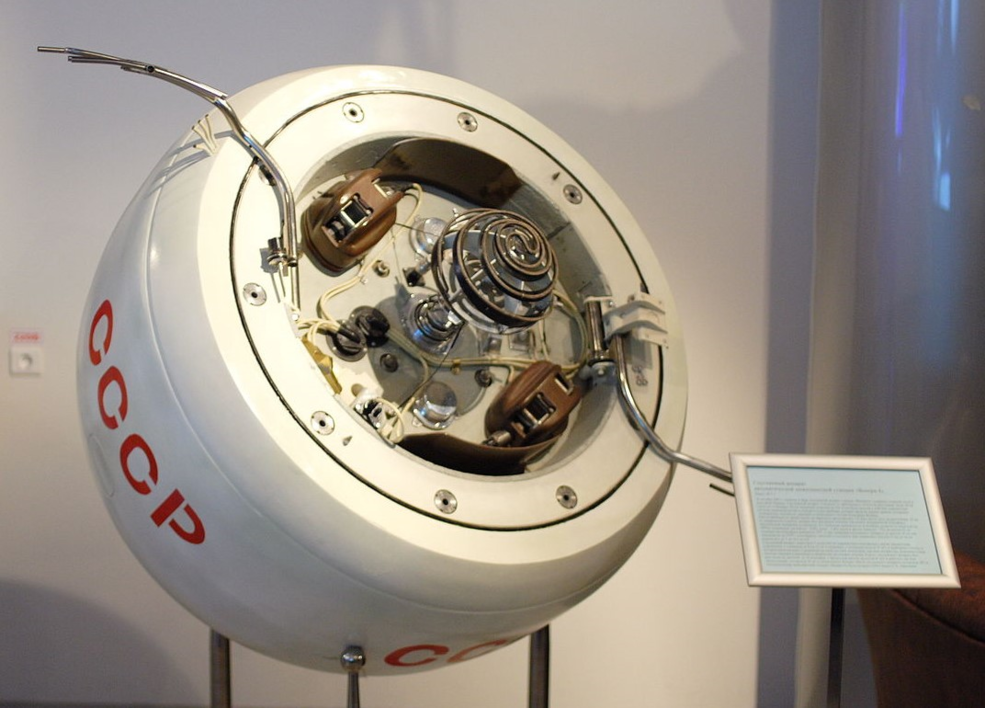

Left: The Soviet Union’s Venera 4 spacecraft, showing the atmospheric entry

probe at bottom. Right: Closeup of the Venera 4 atmospheric entry probe.

Image credits: Courtesy Memorial Museum of Cosmonautics, Moscow.

Taking advantage of the same launch window to Venus, the Soviet Union launched Venera 4 on June 12, with a goal to study the planet’s atmosphere and land a capsule on the planet’s surface. After a 128-day flight from Earth, on Oct. 18, Venera 4 released its 844-pound entry probe. The capsule entered the planet’s atmosphere on the night side, returning data for 93 minutes during its parachute-assisted descent. The Soviets had underestimated the extreme conditions on Venus and at an altitude of 17 miles, the craft stopped transmitting, succumbing to the high temperatures and pressures of the Venusian atmosphere. In March 1968, American and Soviet scientists met at the Kitt Peak National Observatory in Tucson, Arizona, to exchange data and compare results from their respective spacecraft, one of the first international conferences to discuss results from planetary spacecraft. The two countries jointly published the results from Mariner 5 and Venera 4.