On Nov. 13, 1971, Mariner 9 entered orbit around Mars, the first spacecraft to orbit another planet. Managed by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, Mariner 9’s primary 90-day mission included mapping up to 70% of Mars and recording changes in the planet’s atmosphere and surface over time. A dust storm obscured the planet’s surface when Mariner 9 arrived. It cleared after a few weeks, and the spacecraft could begin its mapping mission. It also photographed Mars’ two moons, Phobos and Deimos, in unprecedented detail. The photographs returned by Mariner 9 revealed a planet far more complex than scientists expected based on the limited imagery from earlier spacecraft. The spacecraft operated until October 1972, far beyond its planned mission, and dramatically changed our view of the Red Planet.

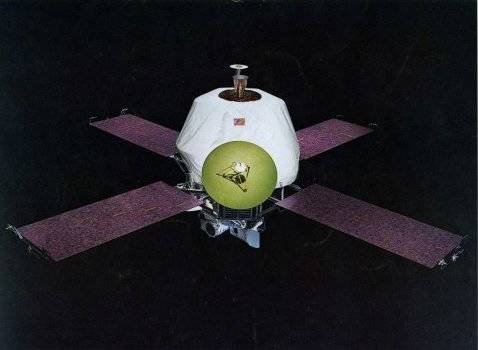

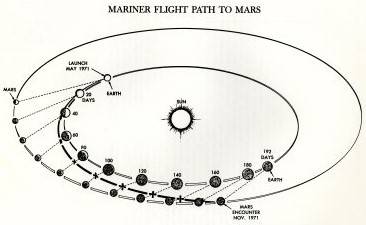

Left: A model of the Mariner 9 spacecraft. Right: Mariner 9’s trajectory from Earth to Mars.

The Mariner-Mars 1971 project planned to insert two spacecraft, Mariner 8 and 9, equipped with cameras and other instruments, into elliptical orbits around Mars to study the planet for a minimum of 90 days. The two spacecraft had complementary but overlapping missions, with one mapping up to 70% of the planet’s surface while the second focused on recording temporal changes in the planet’s atmosphere and on its surface. Following Mariner 8’s launch failure, Mariner 9 picked up the combined objectives of both spacecraft. Mariner 9 launched successfully and after a 167-day interplanetary journey entered an elliptical orbit around Mars on Nov. 13, 1971, the first spacecraft ever to orbit another planet.

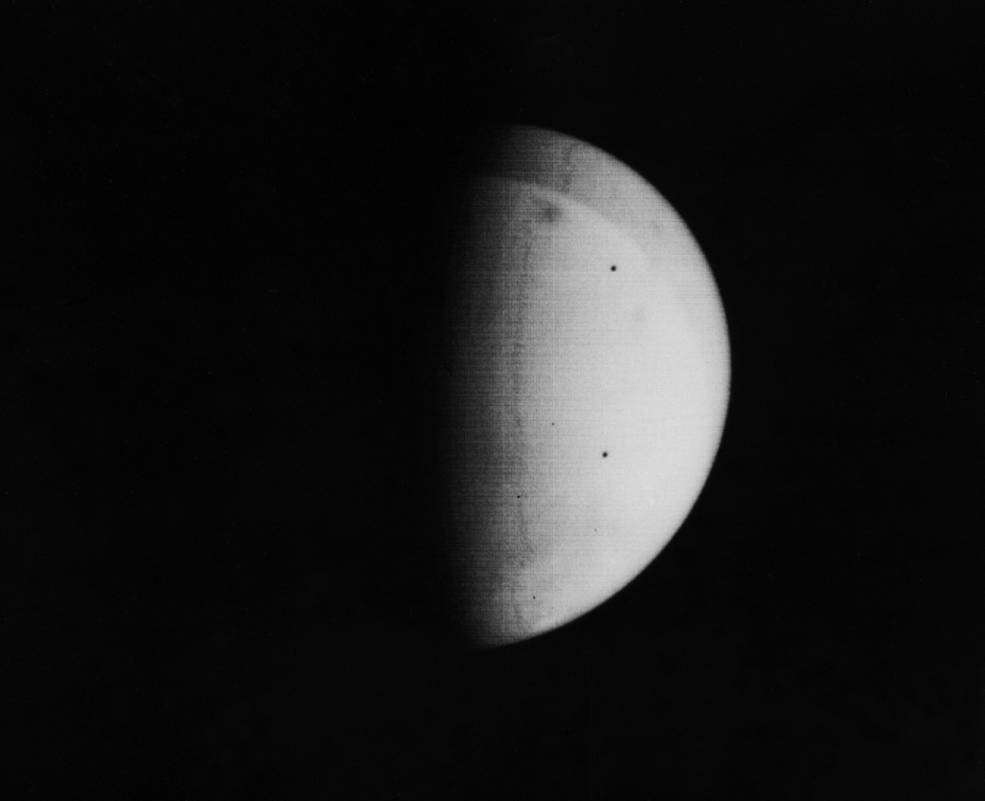

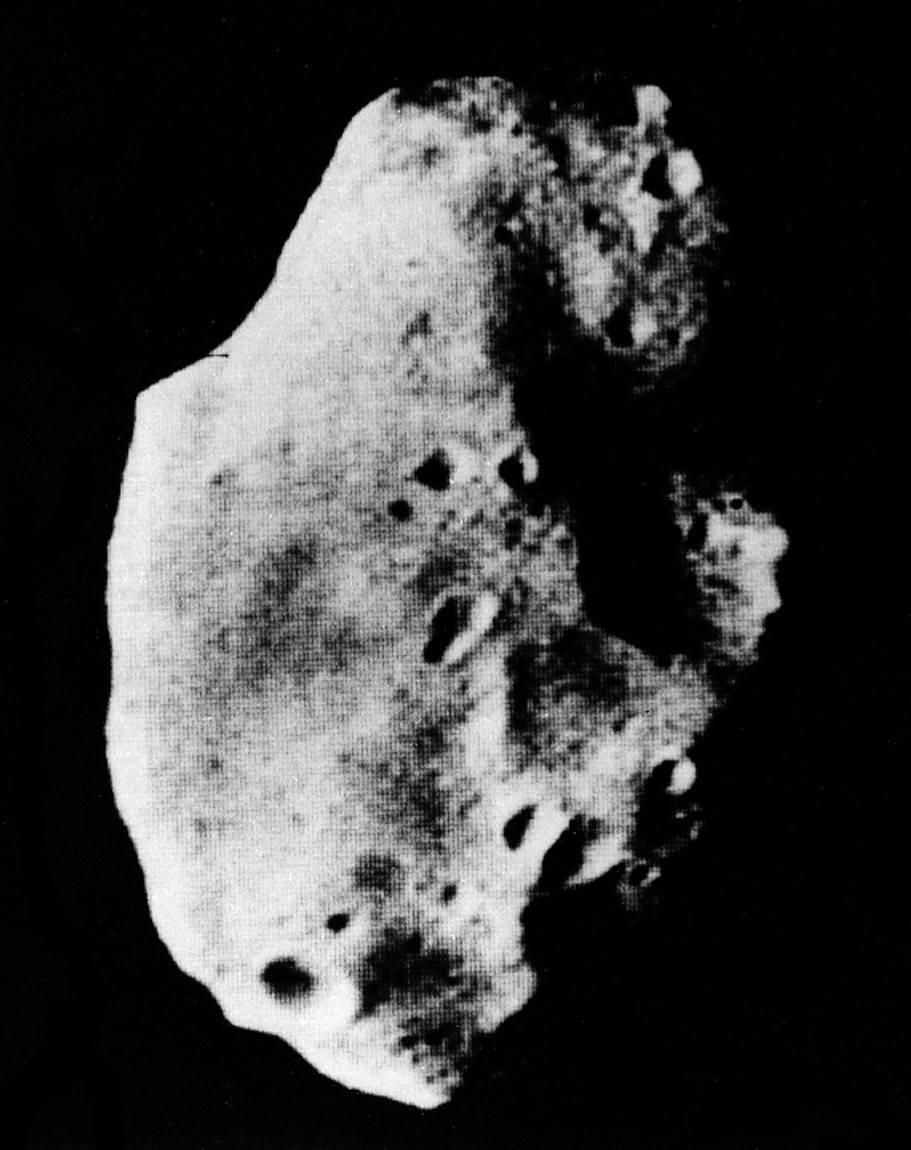

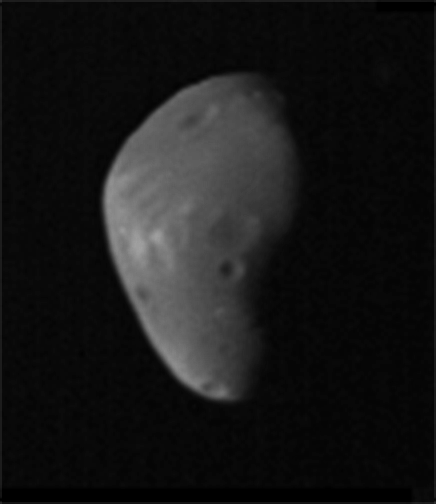

Left: When Mariner 9 arrived, a planet-wide dust storm enveloped Mars, with very few surface features visible. Middle: Photograph of Mars’ larger moon Phobos. Right: Image of Deimos, Mars’ smaller moon.

When Mariner 9 arrived in orbit, a global dust storm obscuring nearly all surface features hampered its primary mapping mission. Only two landmarks, the southern polar cap and the top of what scientists believed was a tall mountain, were visible to the spacecraft’s cameras. Over the next several weeks, as the spacecraft waited for the dust to settle, Mariner 9 turned its gaze on Mars’ two small moons, Phobos and Deimos, returning the first detailed images of these objects. The larger moon, Phobos, a 17-by-14-by-11-mile potato-shaped object, appeared to be heavily cratered, with one crater the result of an impact nearly large enough to have shattered the body. Deimos, the smaller moon with dimensions of 10-by-7-by-7 miles, appeared to have a dustier surface with fewer large impact craters. Based on the moons’ size and appearance, scientists believe they are asteroids captured by Mars in the distant past.

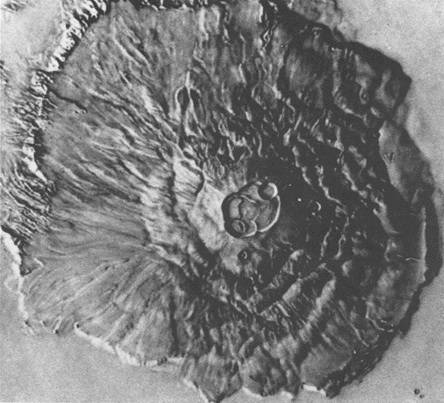

Left: Mariner 9 image of the shield volcano Olympus Mons, the tallest feature in the solar system. Right: Composite image of Valles Marineris, the largest canyon system in the solar system.

The dark spot first visible through the dust storm, and two others becoming visible as the dust cleared, turned out to be volcanoes. The largest of the three, Olympus Mons, dwarfed not only the other two but also the largest shield volcano on Earth, Mauna Loa on the island of Hawaii. The Martian volcano’s summit, topped by a 50-mile-wide caldera, rose 16 miles (72,000 feet) above the surrounding plain, tall enough to be above the planet’s thin atmosphere. The volcano’s base spanned 374 miles, roughly the size of Arizona. Also surprising to scientists, Mariner 9 imaged a canyon system dwarfing anything seen on Earth. The Valles Marineris, in places 120 miles wide and up to 23,000 feet deep, stretched across 2,500 miles of Mars, nearly the equivalent east-west distance of the continental United States. Other areas showed sinuous canyons similar to those carved by flowing water on Earth.

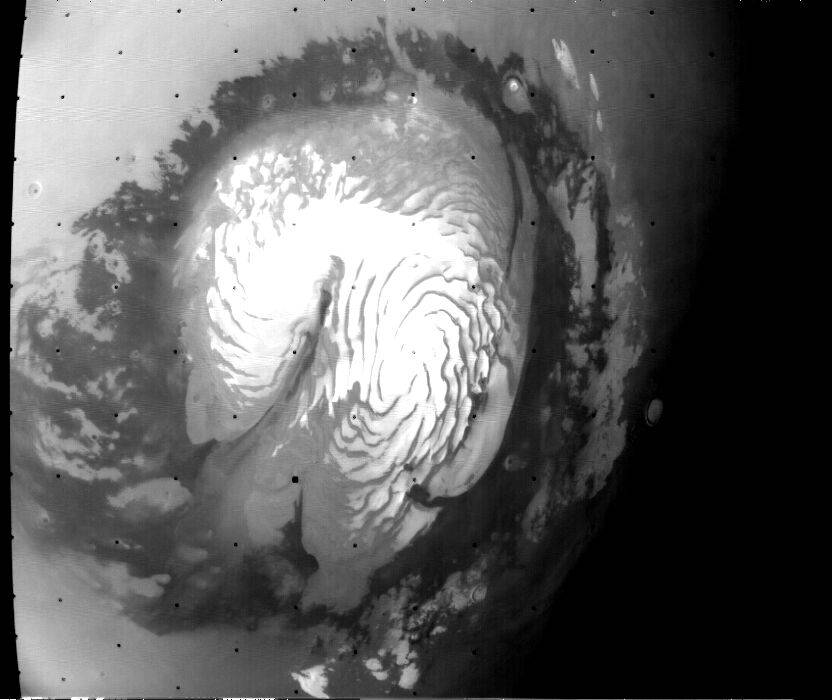

Left: Composite image of Mars’ north polar cap region taken shortly after summer solstice. Right: View of Mars’ horizon with atmospheric haze layers 15 to 25 miles above the planet’s surface.

As Mariner 9 observed the planet over 10 months, it noted seasonal changes. For example, the spacecraft saw the planet’s polar caps receding and advancing much as Earth’s polar caps do. Its instruments indicated the north polar cap to be composed of a mixture of water ice and frozen carbon dioxide. The spacecraft also observed the effects of sandstorms, cloud formations, and haze in Mars’ thin upper atmosphere, thought by scientists to be crystals of frozen carbon dioxide.

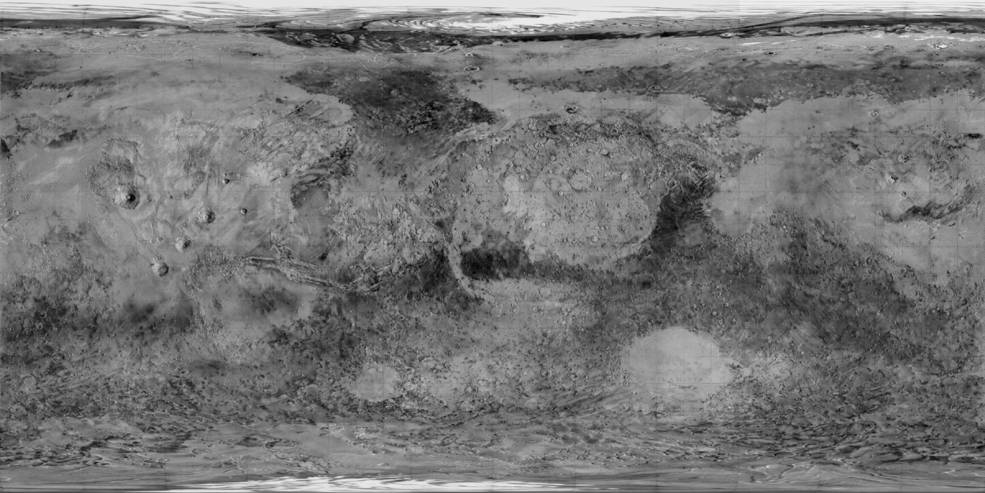

Global map of Mars prepared from Mariner 9 imagery.

Mariner 9 continued to operate until Oct. 27, 1972, well past its 90-day primary mission, returning 7,329 images of the planet. It mapped 85%of its surface – down to a resolution of 0.5 to 1 mile – and its two small moons. The photographs overturned the image of Mars as a Moon-like cratered world, instead showing evidence of past volcanic activity and even the possibility of past surface water. Scientists created the first global map and globe of Mars from Mariner 9’s imagery. The detailed photographs also gave scientists useful information to select candidate landing sites for the Viking landers launched toward Mars in 1975.

John Uri

NASA Johnson Space Center